Mirabal sisters

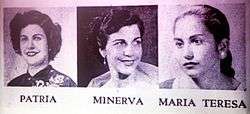

The Mirabal sisters (Spanish pronunciation: [eɾˈmanas miɾaˈβal], Las Hermanas Mirabal) were four Dominican sisters known commonly as Patria, Minerva, María Teresa, and Dedé, who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo (El Jefe) and were involved in clandestine activities against his regime.[1] Three of the four sisters (Patria, Minerva, María Teresa) were assassinated on 25 November 1960. The last sister, Dedé, died of natural causes on 1 February 2014.[2]

The assassinations turned the Mirabal sisters into "symbols of both popular and feminist resistance".[3] In 1999, in the sisters' honor, the United Nations General Assembly designated 25 November the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.[4]

Sisters

| Name | Common name | Birthday | Date of death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patria Mercedes Mirabal Reyes | Patria | 27 February 1924 | 25 November 1960 |

| Bélgica Adela Mirabal Reyes | Dedé | 1 March 1925 | 1 February 2014 |

| María Argentina Minerva Mirabal Reyes | Minerva | 12 March 1926 | 25 November 1960 |

| Antonia María Teresa Mirabal Reyes | María Teresa | 15 October 1935 | 25 November 1960 |

The Mirabal family were farmers from the central Cibao region of the Dominican Republic. The sisters grew up in a middle-class environment, raised by their parents, Enrique Mirabal Fernández and Mercedes Reyes Camilo.[5]

Patria Mercedes Mirabal Reyes

Patria Mercedes Mirabal Reyes, commonly known as Patria, was the oldest of the four Mirabal sisters, born on 27 February 1924. When she was 14, she was sent by her parents to a Catholic boarding school, Colegio Inmaculada Concepción in La Vega. She left school when she was 17 and married Pedro González,[6][7] a farmer, who would later aid her in challenging the Trujillo regime.

Patria is quoted as saying, "We cannot allow our children to grow up in this corrupt and tyrannical regime. We have to fight against it, and I am willing to give up everything, even my life if necessary."[8]

Bélgica Adela Mirabal Reyes

Bélgica Adela Mirabal Reyes, commonly known as Dedé, was the second daughter of the Mirabal family and was born 1 March 1925[9] (sometimes reported as born 29 February 1925).[10] Unlike her sisters, she did not go to college but instead took the role of the tradition homemaker.[10] Dedé stayed home to help with the family business and did not become involved with her sisters' political work. After the murder of her sisters Dedé took care of their children.[10] Between 1992 and 1994 Dedé started the Mirabal Sisters Foundation and the Mirabal Sisters museum to continue her sisters' legacy.[11] Dedé was the last surviving sister of the family. She died at the age of 88, and professed her entire life that it was her destiny to survive so that she was able to "tell their story."[12]

María Argentina Minerva Mirabal Reyes

María Argentina Minerva Mirabal Reyes, commonly known as Minerva, was the third daughter, born on 12 March 1926. At the age of 12, she followed Patria to the Colegio Inmaculada Concepción.[6] After graduating, she enrolled at the University of Santo Domingo. She studied law, but because she had declined Trujillo's sexual advances in 1949,[13][14] she was denied a license to practice.

At university, she met her husband, Manolo Tavárez Justo, who would help her fight the Trujillo regime. Minerva was the most vocal and radical of the Mirabal daughters, and she was arrested and harassed on multiple occasions on orders given by Trujillo himself.[15] She was quoted as saying, "It is a source of happiness to do whatever can be done for our country that suffers so many anguishes. It is sad to stay with one's arms crossed."[8]

Antonia María Teresa Mirabal Reyes

Antonia María Teresa Mirabal Reyes, commonly known as María Teresa, was the fourth and youngest daughter, born on 15 October 1935.[16] She attended the Colegio Inmaculada Concepción, graduated from the Liceo de San Francisco de Macorís in 1954, and went on to the University of Santo Domingo, where she studied mathematics.[17]

After her education, María married Leandro Guzmán. María Teresa was influenced by her older sister Minerva's political views and was involved in the clandestine activities against Trujillo's regime.[16][17] As a result, she was harassed and arrested on the direct orders of Trujillo.[17][18][15] She greatly admired her older sister Minerva and became passionate about Minerva's political views.[6] She once said, "Perhaps what we have most near is death, but that idea does not frighten me. We shall continue to fight for that which is just."[8]

Political activities

Influenced by her uncle, Minerva became involved in the political movement against Trujillo, who was the country's official president from 1930 to 1938 and from 1942 to 1952, but ruled behind the scenes as a dictator from 1930 until his assassination in 1961. Minerva's sisters followed her into the movement: first María Teresa, who joined after staying at Minerva's house and learning about her activities, and then Patria, who joined after witnessing a massacre by some of Trujillo's men while on a religious retreat. Dedé did not join in, partly because her husband, Jaimito, did not want her to.

Minerva, María Teresa, and Patria joined a group called the Movement of the Fourteenth of June. They distributed pamphlets about the many people whom Trujillo had killed, and obtained materials for guns and bombs to use when they eventually openly revolted. Within the group, the sisters called themselves "Las Mariposas" ("The Butterflies"), after Minerva's underground name.[3]

Minerva and María Teresa were incarcerated but were not tortured thanks to mounting international opposition to Trujillo's regime. Their and Patria's husbands, who were also involved in the underground activities, were incarcerated at La Victoria Penitentiary in Santo Domingo.

In 1960, the Organization of American States condemned Trujillo's actions and sent observers. Minerva and María Teresa were freed, but their husbands remained in prison.[13] On a remembrance website, Learn to Question, the author writes, "No matter how many times Trujillo jailed them, no matter how much of their property and possessions he seized, Minerva, Patria and María Teresa refused to give up on their mission to restore democracy and civil liberties to the island nation."[13]

Assassination

On 25 November 1960, Patria, Minerva, María Teresa, and their driver, Rufino de la Cruz, were visiting María Teresa and Minerva's incarcerated husbands. On the way home, they were stopped by Trujillo's henchmen. The sisters and de la Cruz were separated, strangled[19] and clubbed to death. The bodies were then gathered and put in their Jeep, which was run off the mountain road in an attempt to make their deaths look like an accident.[13]

After Trujillo was assassinated on May 30, 1961, General Pupo Román admitted to having personal knowledge that the sisters were killed by Victor Alicinio Peña Rivera, Trujillo's right-hand man, along with Ciriaco de la Rosa, Ramon Emilio Rojas, Alfonso Cruz Valeria, and Emilio Estrada Malleta, members of his secret police force.[20] As to whether Trujillo ordered the killings or whether the secret police acted on its own, one historian wrote, "We know orders of this nature could not come from any authority lower than national sovereignty. That was none other than Trujillo himself; still less could it have taken place without his assent."[21] Also, one of the murderers, Ciriaco de la Rosa, said "I tried to prevent the disaster, but I could not because if I had he, Trujillo, would have killed us all."[22][23]

Aftermath

According to historian Bernard Diederich, the sisters' assassinations "had greater effect on Dominicans than most of Trujillo's other crimes". The killings, he wrote, "did something to their machismo" and paved the way for Trujillo's own assassination six months later.[25]

However, the details of the Mirabal sisters' assassinations were "treated gingerly at the official level" until 1996, when President Joaquín Balaguer was forced to step down after more than two decades in power. Balaguer was Trujillo's protégé and had been the president at the time of the assassinations in 1960 (though, at the time, he "distanced himself from General Trujillo and initially carved out a more moderate political stance").[26]

A review of the history curriculum in public schools in 1997 recognized the Mirabals as national martyrs.[3] The post-Balaguer era has seen a marked increase in homages to the Mirabal sisters, including an exhibition of their belongings at the National Museum of History and Geography in Santo Domingo and the transformation of Trujillo's obelisk into a mural dedicated in their honor.

After the assassinations, the surviving sister, Dedé, devoted her life to the legacy of her sisters. She raised their six children, including Minou Tavárez Mirabal, Minerva's daughter, who has served as deputy for the National District in the lower house of the Dominican Congress since 2002 and was deputy foreign minister before that (1996–2000). Of Dedé's own three children, Jaime David Fernández Mirabal is the minister for environment and natural resources and a former vice president of the Dominican Republic. In 1992, Dedé created the Mirabal Sisters Foundation, and in 1994, she opened the Mirabal Sisters Museum in the sisters' hometown, Salcedo.[24] She published a book, Vivas en su Jardín, on 25 August 2009.[27] She lived in the house in Salcedo where the sisters were born until her death in 2014, aged 88.[28]

Legacy

On 17 December 1999, the United Nations General Assembly designated 25 November as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women in honor of the sisters. It marks the beginning of a 16-day period of Activism against Gender Violence.[4] The last day of that period, 10 December, is International Human Rights Day.

On 21 November 2007, Salcedo Province was renamed Hermanas Mirabal Province.[29][30][31][32]

Hermanas Mirabal station of the Santo Domingo Metro is named to honor the Mirabal sisters.

The 200 Dominican pesos bill features the sisters, and a stamp was issued in their memory.[3]

The 137-foot obelisk that Trujillo built in 1935 to commemorate the renaming of the capital city from Santo Domingo to Ciudad Trujillo has been covered with murals honoring the sisters. In 1997, the telecommunications company CODETEL (now Claro) sponsored a mural by Elsa Núñez. Every few years, the mural changes.[33]

In 2005, Amaya Salazar created one;[34] in 2011, Banco del Progreso sponsored Dustin Muñoz to redo the mural.[35]

In 2019, the southeast corner of 168th street and Amsterdam Avenue in Washington Heights, Manhattan was designated “Mirabal Sisters Way” by the Council of the City of New York.[36] In addition there is a school campus in Washington Heights, Manhattan, Mirabal Sisters Campus.[37]

Being globally recognized as a symbol of social justice and feminism, the sisters have inspired the creation of many organizations that focus on keeping their legacy alive through social actions. An example of one of these organizations is the Mirabal Sisters Cultural and Community Center, a non-profit organization that seeks to improve the status of immigrant families.[38]

In popular culture

- In 1994, Dominican-American author Julia Alvarez published her novel In the Time of the Butterflies, a fictionalized account of the lives of the Mirabal sisters. Alvarez called the sisters "feminist icons" and "a reminder that we have our revolutionary heroines, our Che Guevaras, too".[3] The novel was adapted into a 2001 movie of the same name, starring Salma Hayek as Minerva, Edward James Olmos as Trujillo, and singer Marc Anthony in a supporting role.[24]

- The sisters are mentioned in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, a 2007 novel by Dominican-American writer Junot Díaz.

- The story is fictionalized in the children's book How the Butterflies Grew Their Wings by Jacob Kushner.

- Chilean filmmaker Cecilia Domeyko produced Code Name: Butterflies, a documentary about the Mirabal sisters. It contains interviews with Dedé and other members of the Mirabal family.[24]

- Actress Michelle Rodriguez co-produced the film Trópico de Sangre, which recounts the lives of the sisters. She also starred in the film as Minerva. Dedé Mirabal participated in the development of the film.[39]

- Mario Vargas Llosa's 2000 novel, The Feast of the Goat, portrays the assassination of Trujillo and its effect on the lives of Dominicans. It refers often to the Mirabal sisters.[40]

- Dominican professional tennis player Michael-Ray Pallares González is a second cousin once-removed of the Mirabal sisters.

References

- "International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women".

- https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-internacional-42060899

- Rohter, Larry (15 February 1997). "The Three Sisters, Avenged: A Dominican Drama". New York Times.

- "International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women". United Nations. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Peter Farrington (17 December 2013). "Mirabal Sisters of The Dominican Republic". The REAL Dominican Republic. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "The Mirabal Sisters- The Nov. 25th Revolution", "Safe World for Women", 7 March 2016

- "ENCOUNTER WITH EL JEFE". Becoming The Butterflies: The Political Participation of the Mirabal Sisters. p. 2.

- "Mirabal Sisters History", "Mirabal Sisters Cultural and Community Center", 7 March 2016

- "Dedé Mirabal Reyes" (in Spanish). Casa Museo Hermanas Mirabal. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Garcia, Franklin (3 February 2014). "Last Surviving Mirabal Sister, Doña Dede, Dead at 88". HuffPost. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Rohter, Larry (15 February 1997). "The Three Sisters, Avenged: A Dominican Drama". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Dedé Mirabal Reyes and Minou Tavárez Mirabal to speak Nov. 6". Middlebury. 17 December 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "The Mirabal Sisters". LearnToQuestion.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Ferullo, Giovanna (26 August 2011). "Violencia y discriminación de la mujer, un problema muy grave en R.Dominicana". MSN Noticias (in Spanish). Panamá. EFE. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

(...) Once años antes del triple asesinato, 'había habido una intención del dictador de sumar a mi madre a la lista de mujeres que le pertenecían, como las vacas de sus fincas', algo a lo que Minerva se negó, contó Tavárez Mirabal.

A partir de allí nació la 'obsesión' de Trujillo contra la familia Mirabal, que empeoró cuando se percató de que una mujer, Minerva, era la 'organizadora del movimiento de oposición más importante que tuvo que enfrentar en 30 años de dictadura', añadió. - Nancy Pineda-Madrid "Celebrating Our Latina Feminists Foremothers", "Project Muse", 7 March 2016

- "Biography". Maria Teresa Mirabal. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "The Mirabal Sisters: The three "butterflies" who were killed because of their activities against the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo". The Vintage News. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Jewell, Hannah (2 November 2017). 100 Nasty Women of History: Brilliant, badass and completely fearless women everyone should know. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781473671270.

- "Las Mariposas: The Mirabal Sisters' Role as Heroines of the Dominican Republic". stmuhistorymedia.org. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Mirabal Sisters of The Dominican Republic". TheRealDR.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Virgilio Pina Chevalier, La era de Trujillo. Narraciones de Don Cucho, p. 151.

- "The Murder and Assassination of the Mirabal Sisters". The Real Dominical Republic. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "THE ASSASSINATION The Murder of the Sisters Mirabal". Learning to Question. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Garcia, Franklin (3 February 2014). "Last Surviving Mirabal Sister, Doña Dede, Dead at 88". Huffington Post.

- Bernard Diederich (1999). Trujillo: The Death of the Dictator. Markus Wiener Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1558762060.

- Kershaw, Sarah (15 July 2002). "Joaquín Balaguer, 95, Dies; Dominated Dominican Life". New York Times.

- Amazon (2009). Vivas en el Jardin. ISBN 0307474534.

- Tennant, Paul; Yadira Betances (3 February 2014). "Dominican heroine dies". Eagle-Tribune. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Camara de Diputados. "Proyecto de Ley mediante el cual se modifica el nombre de la provincia Salcedo a provincia Hermanas Mirabal" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Diario Libre. "Provincia Salcedo pasa a llamarse "Hermanas Mirabal"" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- El Tiempo. "La historia de las hermanas Mirabal" (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Educando. "Las hermanas Mirabal en otra dimensión" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Keys, Janette (29 June 2011). "New Painting on the Obelisk". Colonial Zone News Blog.

- "Restauran Obelisco del Malecón". Hoy (in Spanish). 3 March 2005.

- Brito, Reynaldo (27 July 2011). "Obelisco del malecón restaurado con obra de Dustin Muñoz". Imagenes Dominicanas.

- "INVITATION: Sun. 2/10 Street Co-Naming Ceremony to Honor the Mirabal Sisters". Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Mirabal Sisters Campus". Childrens Aid NYC. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Sisters, Mirabal. "Misión". www.mirabalcenter.org. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Michelle Rodriguez Producing and Starring in Historical Feature". Michelle-rodriguez.com. 25 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Author, Nobel Prize Winner Mario Vargas Llosa, The Feast of the Goat, translated from Spanish by Edith Grossman. Originally published by Alfguana in Spain under the title La fiesta del chivo . 2000. ISBN 0-312-42027-7

External links