Mir Taqi Mir

Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir (February 1723 - 21 September 1810), also known as Mir Taqi Mir or Meer Taqi Meer, was an Urdu poet of the 18th century Mughal India, and one of the pioneers who gave shape to the Urdu language itself. He was one of the principal poets of the Delhi School of the Urdu ghazal and is often remembered as one of the best poets of the Urdu language. His takhallus (pen name) was Mir. He spent the latter part of his life in the court of Asaf-ud-Daulah in Lucknow.

Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir | |

|---|---|

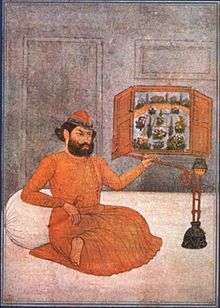

Mir Taqi Mir in 1786 | |

| Born | February 1723 Agra, Mughal India |

| Died | 21 September 1810 (aged 87) Lucknow, Oudh State, Mughal India |

| Pen name | Mir |

| Occupation | Urdu poet |

| Period | Mughal India |

| Genre | Ghazal, Mathnavi, Persian Poetry |

| Subject | Love, philosophy |

| Notable works | Faiz-e-Mir Zikr-e-Mir Nukat-us-Shura Kulliyat-e-Farsi Kulliyat-e-Mir |

Life

The main source of information on Mir's life is his autobiography Zikr-e-Mir, which covers the period from his childhood to the beginning of his sojourn in Lucknow.[1] However, it is said to conceal more than it reveals,[2] with material that is undated or presented in no chronological sequence. Therefore, many of the 'true details' of Mir's life remain a matter of speculation.

Mir was born in Agra, India (then called Akbarabad and ruled by the Mughals) in August or February 1723. His grandfather migrated from Hejaz to Hyderabad State, then to Akbarabad. His philosophy of life was formed primarily by his father, a religious man with a large following, whose emphasis on the importance of love and the value of compassion remained with Mir throughout his life and imbued his poetry. Mir's father died while the poet was in his teens. He left Agra for Delhi a few years after his father's death, to finish his education and also to find patrons who offered him financial support (Mir's many patrons and his relationship with them have been described by his translator C. M. Naim).[3]

Some scholars consider two of Mir's masnavis (long narrative poems rhymed in couplets), Mu'amlat-e-ishq (The Stages of Love) and Khwab o khyal-e Mir ("Mir's Vision"), written in the first person, as inspired by Mir's own early love affairs,[4] but it is by no means clear how autobiographical these accounts of a poet's passionate love affair and descent into madness are. Especially, as Frances W. Pritchett points out, the austere portrait of Mir from these masnavis must be juxtaposed against the picture drawn by Andalib Shadani, whose inquiry suggests a very different poet, given to unabashed eroticism in his verse.[5]

Mir lived much of his life in Mughal Delhi. Kuchha Chelan, in Old Delhi was his address at that time. However, after Ahmad Shah Abdali's sack of Delhi each year starting 1748, he eventually moved to the court of Asaf-ud-Daulah in Lucknow, at the king's invitation. Distressed to witness the plundering of his beloved Delhi, he gave vent to his feelings through some of his couplets.

کیا بود و باش پوچھے ہو پورب کے ساکنو

ہم کو غریب جان کے ہنس ہنس پکار کے

دلّی جو ایک شہر تھا عالم میں انتخاب

رہتے تھے منتخب ہی جہاں روزگار کے

جس کو فلک نے لوٹ کے ویران کر دیا

ہم رہنے والے ہیں اسی اجڑے دیار کے

Mir migrated to Lucknow in 1782 and stayed there for the remainder of his life. Though he was given a kind welcome by Asaf-ud-Daulah, he found that he was considered old-fashioned by the courtiers of Lucknow (Mir, in turn, was contemptuous of the new Lucknow poetry, dismissing the poet Jur'at's work as merely 'kissing and cuddling'). Mir's relationships with his patron gradually grew strained, and he eventually severed his connections with the court. In his last years Mir was very isolated. His health failed, and the untimely deaths of his daughter, son and wife caused him great distress.[6]

He died of a purgative overdose on Friday, 21 September 1810.[7] The marker of his burial place was removed in modern times when a railway was built over his grave.[8]

Literary life

His complete works, Kulliaat, consist of six Diwans containing 13,585 couplets, comprising all kinds of poetic forms: ghazal, masnavi, qasida, rubai, mustezaad, satire, etc.[7] Mir's literary reputation is anchored on the ghazals in his Kulliyat-e-Mir, much of them on themes of love. His masnavi Mu'amlat-e-Ishq (The Stages of Love) is one of the greatest known love poems in Urdu literature.

Mir lived at a time when Urdu language and poetry was at a formative stage – and Mir's instinctive aesthetic sense helped him strike a balance between the indigenous expression and new enrichment coming in from Persian imagery and idiom, to constitute the new elite language known as Rekhta or Hindui. Basing his language on his native Hindustani, he leavened it with a sprinkling of Persian diction and phraseology, and created a poetic language at once simple, natural and elegant, which was to guide generations of future poets.

The death of his family members,[7] together with earlier setbacks (including the traumatic stages in Delhi), lend a strong pathos to much of Mir's writing – and indeed Mir is noted for his poetry of pathos and melancholy.

Mir and Mirza Ghalib

Mir's famous contemporary, also an Urdu poet of no inconsiderable repute, was Mirza Rafi Sauda. Mir Taqi Mir was often compared with the later day Urdu poet, Mirza Ghalib. Lovers of Urdu poetry often debate Mir's supremacy over Ghalib or vice versa. It may be noted that Ghalib himself acknowledged, through some of his couplets, that Mir was indeed a genius who deserved respect. Here are two couplets by Mirza Ghalib on this matter.

Reekhta ke tum hī ustād nahīṅ ho ğhālib |

You are not the only master of Rekhta, Ghalib |

| —Mirza Ghalib |

Ghalib apna yeh aqeeda hai baqaul-e-Nasikh |

Ghalib! It's my belief in the words of Nasikh[9] |

| —Mirza Ghalib |

Ghalib and Zauq were contemporary rivals but both of them believed the superiority of Mir and also acknowledged Mir's superiority in their poetry.

Famous couplets

Some of his impeccable couplets are:

Hasti apni habab ki si hai |

My life is like a bubble |

Dikhaai diye yun ki bekhud kiya |

She appeared in such a way that I lost myself And went by taking away my 'self' with her |

At a higher spiritual level, the subject of Mir's poem is not a woman but God. Mir speaks of man's interaction with the Divine. He reflects upon the impact on man when God reveals Himself to the man.

Dikhaai diye yun ke bekhud kiya |

When I saw You (God) I lost all sense of self |

Gor kis diljale ki hai ye falak? |

What heart-sick sufferer's grave is the sky? |

Ashk aankhon mein kab nahin aata? |

From my eye, when doesn't a tear fall? |

Bekhudi le gai kahaan humko, |

Where has selflessness taken me |

Ibtidaa-e-ishq hai rotaa hai kyaa |

It's the beginning of Love, why do you wail |

Likhte ruqaa, likhe gaye daftar |

Started with a scroll, ended up with a record |

Deedani hai shikastagi dil ki |

Worth-watching is my heart's crumbling |

Baad marne ke meri qabr pe aaya wo 'Mir' |

O Mir, he came to my grave after I'd died |

Mir ke deen-o-mazhab ka poonchte kya ho un nay to |

What can I tell you about Mir's faith or belief? |

Mir Taqi Mir in fiction

- Khushwant Singh's famous novel Delhi: A Novel gives very interesting details about the life and adventures of the great poet.

- Mah e Mir is a 2016 Pakistani biographical film directed by Anjum Shahzad and Fahad Mustafa plays the lead role of Mir Taqi Mir.

Major works

- "Nukat-us-Shura" Biographical dictionary of Urdu poets of his time, written in Persian.

- "Faiz-e-Mir" Collection of five stories about Sufis & faqirs, said to have been written for the education of his son Mir Faiz Ali.[11]

- "Zikr-e-Mir" Autobiography written in Persian language.

- "Kulliyat-e-Farsi" Collection of poems in Persian language

- "Kulliyat-e-Mir" Collection of Urdu poetry consisting of six diwans (volumes).

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Awal

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Duam

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Suam

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Chaharam

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Panjam

- Kulliyat e Mir Deewan Shisham

- Mir Taqi Mir Ki Rubaiyat

See also

- List of Urdu poets

- Ghazal

- Mah-e-Meer

References

- Naim, C M (1999). Zikr-i-Mir, The Autobiography of the Eighteenth Century Mughal Poet: Mir Muhammad Taqi Mir (1723–1810), Translated, annotated and with an introduction by C. M. Naim. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman. "The Poet in the Poem" (PDF).

- Naim, C. M. (1999). "Mir and his patrons" (PDF). Annual of Urdu Studies. 14.

- Russell, Ralph; Khurshidul Islam (1968). Three Mughal Poets: Mir, Sauda, Mir Hasan. Harvard University Press.

- Pritchett, Frances W. "Convention in the Classical Urdu Ghazal: The Case of Mir".

- Matthews, D. J.; C. Shackle (1972). An anthology of classical Urdu love lyrics. Oxford University Press.

Mir.

- Legendary Urdu poet Mir Taqi Mir passed away, [The Times of India], Rajiv Srivastava, TNN, 19 September 2010, 05.58am IST

- Dalrymple, William (1998). The Age of Kali. Lonely Planet. p. 44. ISBN 1-86450-172-3.

- Shaikh Imam Bakhsh Nasikh of Lucknow, a disciple of Mir.

- Article in The Asian Age by Javed Anand

- Foreword by Dr. Masihuzzaman in Kulliyat-e-Mir Vol-2, Published by Ramnarianlal Prahladdas, Allahabad, India.

- Lall, Inder jit; Mir A Master Poet; Thought, 7 November 1964

- Lall, Inder jit; Mir The ghazal king; Indian & Foreign Review, September 1984

- Lall, Inder jit; Mir—Master of Urdu Ghazal; Patriot, 25 September 1988

- Lall, Inder jit; 'A Mir' of ghazals; Financial Express, 3 November

Further reading

- Mīr Taqī Mīr (1999). Zikr-i Mir: the autobiography of the eighteenth century Mughal poet, Mir Muhammad Taqi ʻMir', 1723-1810. Translated by C. M. Naim. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195645880. OCLC 42955012.

- Khurshidul Islam; Ralph Russell (1994). Three Mughal Poets: Mir, Sauda, Mir Hasan. OUP India. ISBN 978-0-19-563391-7.

- Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Shiʻr-i shor angez : ghazaliyāt-i Mīr kā muḥaqiqānah intikhāb Qaumī Kaunsil barāʼe Farogh-i Urdū Zabān, 2006 (4-volume study on ghazals of Mīr Taqī Mīr)

- The Anguished Heart: Mir and the Eighteenth Century: 'The Golden Tradition, An Anthology of Urdu Poetry', Ahmed Ali, pp 23–54; Poems:134-167, Columbia University Press, 1973/ OUP, Delhi, 1991

- Kumar, Ish (1996). Mir Taqi Mir. Makers of Indian Literature (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-0186-0. OCLC 707081400.