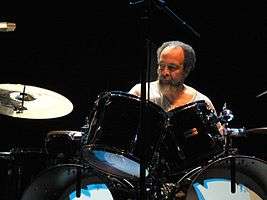

Milford Graves

Milford Graves, born August 20, 1941[1] in Jamaica, Queens,[2][3] is an American jazz drummer, percussionist, Professor Emeritus of Music,[4][5] researcher/inventor,[6][7] visual artist/sculptor,[8][9][10][11] gardener/herbalist,[12] [13] and martial artist.[14][15] He is a co-founder of ÉlpisÉremo Inc. and QuantumEpigenesys.[16] Graves is noteworthy for his early avant-garde contributions in the 1960s with Paul Bley, Albert Ayler, and the New York Art Quartet, and is considered to be a free jazz pioneer, liberating percussion from its timekeeping role. The composer and saxophonist John Zorn referred to Mr. Graves as "basically a 20th-century shaman."[17]

Milford Graves | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | 20 August 1941 Jamaica, Queens, New York, United States |

| Genres | Jazz, free jazz, avant-garde jazz, world music |

| Occupation(s) | musician, herbalist, acupuncturist, college professor |

| Instruments | Drums, percussion, timbales, conga drums, vocals, |

| Labels | ESP, Prestige, Fontana, RCA, Tzadik |

| Associated acts | Albert Ayler, New York Art Quartet, Paul Bley, Don Pullen |

| Website | milfordgraves.com |

Biography

Graves began playing drums at age three, and was introduced to the congas at age eight.[18] He also studied timbales and African hand drumming at an early age. By the early 1960s, he was leading dance bands and playing in Latin/Afro Cuban ensembles in New York on bills alongside Cal Tjader and Herbie Mann.[19] His group, the Milford Graves Latino Quintet, included saxophonist Pete Yellin, pianist Chick Corea, bassist Lisle Atkinson, and conga player Bill Fitch.[20][21]

In 1962, Graves heard the John Coltrane quartet with Elvin Jones, whose drumming made a strong impression.[22] The following year, Graves acquired a standard drum set from pianist Hal Galper and began using it regularly.[20] That summer, percussionist Don Alias invited Graves to Boston for a residency, and Graves began playing with saxophonist Giuseppi Logan.[23]

In 1964, during a visit to New York, Logan introduced Graves to trombonist Roswell Rudd and saxophonist John Tchicai. Graves "wound up playing with them for half an hour, astonishing Rudd and Tchicai, who promptly invited him to join what became The New York Art Quartet."[24] Rudd recalled that Graves's "playing was like an anti-gravity vortex, in which you could either float or fly depending on your impulse."[22] According to Tchicai, "Graves simply baffled both Rudd and I in that, at that time, we hadn't heard anybody of the younger musicians in New York that had the same sense of rhythmic cohesion in polyrhythms or the same sense of intensity and musicality."[25] Tchicai also stated that Don Moore, the original New York Art Quartet bassist, "became so frightened of this wizard of a percussionist that he decided that this couldn't be true or possible and therefore refused to play with us."[26]

That same year, Graves also participated in the "October Revolution in Jazz" organized by Bill Dixon,[27] and appeared on a number of recordings, including the New York Art Quartet's self-titled debut album, Giuseppi Logan's debut album, which also featured pianist Don Pullen and bassist Eddie Gómez, Paul Bley's Barrage, Montego Joe's Arriba! Con Montego Joe (which also featured Chick Corea and Gómez), and the Jazz Composer's Orchestra's Communication. Graves also briefly played with Albert Ayler's trio, which included bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray, as a second drummer. This combination of musicians inspired John Coltrane to add Rashied Ali as a second drummer the following year.[28]

In 1965, Graves continued to expand his horizons, studying the tabla with Wasantha Singh[29] and recording with Miriam Makeba on Makeba Sings!. He also recorded and released a percussion album titled Percussion Ensemble, which featured drummer Sonny Morgan. Val Wilmer wrote that the recording "remains just about the most brilliantly conceived and executed percussion album to date."[30] That year, Graves also recorded on the New York Art Quartet's second album Mohawk, on Montego Joe's second album, Wild & Warm, on Lowell Davidson's sole release, and on a second album with Giuseppi Logan, again working with Don Pullen. Graves and Pullen soon formed a duo, and in 1966 they recorded and released In Concert at Yale University, followed by Nommo, on their SRP ("Self Reliance Project") label.

In 1967, Graves joined Albert Ayler's band, replacing Beaver Harris.[28] The group performed at Slugs' Saloon,[31] at the Newport Jazz Festival,[28] and, on July 21, at John Coltrane's funeral.[32][33] (Recordings of this performance were released in 2004 on the compilation Holy Ghost.) Later that year, the group recorded Love Cry. Graves left Ayler's band when Impulse! began pushing Ayler in a more commercial direction.[28][34]

In the late 1960s, Graves recorded Black Woman with Sonny Sharrock and began playing with drummers Andrew Cyrille and Rashied Ali on a series of concerts titled "Dialogue of the Drums."[35] Graves and Cyrille also recorded and released an album without Ali and with the title "Dialogue of the Drums" in 1974. During this time, Graves studied to become a medical technician and managed a lab for a veterinarian.[8] In 1973, Bill Dixon helped secure Graves a teaching position at Bennington College, where Graves taught until 2012. (Dixon had previously brought Jimmy Lyons, Jimmy Garrison, Alan Shorter, and Alan Silva to Bennington.)[4][36] In 1977, Graves released two albums under his own name: Bäbi, which featured reed players Arthur Doyle and Hugh Glover, and Meditation Among Us, with a Japanese jazz quartet composed of Kaoru Abe, Toshinori Kondo, Mototeru Takagi, and Toshiyuki Tsuchitori. During the early 1980s, Graves also began working with dancer Min Tanaka.[37]

In the years that followed, Graves toured and recorded in a quartet setting with drummers Cyrille, Kenny Clarke, and Famoudou Don Moye, recorded a duo album with David Murray, and performed and recorded with the New York Art Quartet in celebration of their 35th anniversary.[38][39] He also recorded two solo albums, Grand Unification (1998) and Stories (2000), as well as albums with John Zorn, Anthony Braxton, William Parker, and Bill Laswell. In 2008 and 2012, Graves performed with Lou Reed.[31] In 2017, Graves played on Sam Amidon's album The Following Mountain. 2018 saw Graves performing with bassist Shahzad Ismaily,[40] as well as the release of the documentary Milford Graves Full Mantis, directed by Graves's former student, Jake Meginsky, along with Neil Cloaca Young.[41] In 2019, Graves played in a duo setting with pianist Jason Moran.[42] Alice in Chains vocalist William DuVall also directed a documentary about Graves titled Ancient to Future: The Wisdom of Milford Graves. However, the film has been in post-production status since 2013 and has not been released as of 2020.[43]

In 2000, Graves was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition,[44] and in 2015 he received a Doris Duke Foundation Impact Award.[45]

Musical Style

Graves, along with Sunny Murray and Rashied Ali, was one of the first jazz musicians to free the drums from their traditional time-keeping role, having developed "a conception of... music that went beyond jazz and the ching-a-ding of the ride cymbal."[46] Val Wilmer described Graves as

...a percussionist with an amazing technique. Graves moved around his drumset with astonishing speed, beating rapid two-handed tattoos on every surface. Each stroke was clearly defined so that there were no rolls in the conventional sense; the emphasis was on clarity. He used his cymbals in the way another drummer might use a gong or another drum. With the NYAQ, Graves's snare drum was tuned high as was the norm, but already his tom-toms were producing a deeper sound than usual. By the end of the 'sixties, though, he had dispensed with the snare and his three tom-toms were tuned as loosely as is common in rock today... Graves was probably the first American drummer to remove all of his bottom heads because of their tendency to absorb sound.[47]

Wilmer also wrote:

His bass drum... is in frequent use, and he habitually holds his sticks by the tip... Graves was using matched grip before it became fashionable, and he has another unique grip which enables him to hold two sticks and play on two surfaces virtually simultaneously. Sometimes he holds a huge mallet or maracas in the same hand as a regular drumstick, beating with this combination on the same surface or switching alternately from one beater to the other. He occasionally takes a small pair of tuned bongoes, places them in front of him on the skin of one tom-tom and hits them in that position. The result is a percussive maelstrom of multi-layered intensity.[48]

John Szwed wrote that Graves "did not use a standard drum setup and sometimes hit the bass drum with a stick or kicked it instead of using a pedal, or he played the snare with a tree branch with the leaves still intact."[49]

Graves believes that "most drummers are over-occupied with the playing of rhythms and insufficiently with the actual sound," and that it is "important for drummers to study the actual membrane, to try for different sounds or a different feeling by playing on every part of the skin and not merely the same area over and over again..."[50] He stated that "[i]f you know how to manipulate your skins, you can make that dispersed sound - slides, portamento style, sustained tone. Instead of letting your stick free rebound, you can mute it, slide it on there. It calls for greater physicality."[51] Graves told Aakash Mittal: "when I play, I do more than vertical strokes. I’m not just bah-bop bah-bop. My thing is moving around, touching the skins, knowing about momentum and position at the same time."[52] In an interview with Paul Burwell, Graves stated: "I relate the drum skin to a body of water... As a musician, you are schooling yourself to deal with some of the most sensitive things in the universe: emotion, frequency, life, the vital force... we're involved with one of the most subtle things in life. Sounds - that's it!"[53]

Graves has also been very outspoken about his feelings concerning the role of the drummer: "I couldn't understand how a guy would sit and play a basic beat all the time. In African drumming, the drum is in the forefront. Timekeeping for the drummer? I said no way."[20] He stated: "You just can’t stay in the background; that’s not the nature of the instrument. Most drummers are so reduced. And one of the most disrespectful things the drummer can encounter is when they put the drums either in the right or left side corner of the stage, or if they put you there, they’ve got people in front of you."[31] He suggested that drummers not take "a greater or lesser role, but an equal role... Not reducing yourself to the point that you were considered just a drummer, not a musician. I resented that more than anything."[51]

Non-Musical Interests

Graves has also pursued scientific and homeopathic projects related to music-based healing.[54] In the 1960s, Graves invented a form of martial art called "Yara", based on the movements of the Praying Mantis, an African ritual dance. (Yara means "nimbleness" in the Yoruba language.)[55] In 2013, Graves received co-inventor status on a patent for a "[m]ethod and device for preparing non-embryonic stem cells" using the rhythmic properties of the human heartbeat.[56] He has also used ECG tracings and heart sounds as generative principles for musical compositions.

Discography

As leader

- 1965: Percussion Ensemble (ESP) with Sunny Morgan

- 1977: Meditation Among Us (Kitty) with Kaoru Abe, Toshinori Kondo, Mototeru Takagi, and Toshiyuki Tsuchitori

- 1977: Bäbi (IPS, reissued on Corbett Vs. Dempsey) with Arthur Doyle, Hugh Glover

- 1998: Grand Unification (Tzadik)

- 2000: Stories (Tzadik)

As sideman

with Montego Joe

With Giuseppi Logan

- Giuseppi Logan Quartet (ESP)

- More Giuseppi Logan (ESP)

With Paul Bley

- Barrage (ESP)

With New York Art Quartet

With the Jazz Composer's Orchestra

With Miriam Makeba

- Makeba Sings! (RCA)

With Lowell Davidson

- The Lowell Davidson Trio (ESP)

With Don Pullen

- At Yale University (PG)

- Nommo (SRP)

With Albert Ayler

With Sonny Sharrock

With Andrew Cyrille

- Dialogue of the Drums (IPS)

With Various Artists

- New American Music Volume 1: New York Section / Composers of the 1970's (Folkways)

With Sun Ra

- Untitled Recordings (Transparency)

With Kenny Clarke/Andrew Cyrille/Famoudou Don Moye

- Pieces of Time (Soul Note)

With David Murray

- Real Deal (DIW)

With John Zorn

With Anthony Braxton & William Parker

With Bill Laswell

- Space/Time - Redemption (TUM Records)

- The Stone (Back In No Time) (M.O.D. Technologies)

With Sam Amidon

Filmography

- The Breath Courses Through Us (2013) by Alan Roth

- River of Fundament (2014) by Matthew Barney

- Milford Graves Full Mantis (2018) by Jake Meginsky

Bibliography

- Graves, Milford. (2007) "Book of Tono-Rhythmology." In Arcana II: Musicians on Music ed. John Zorn, 110-117. New York, Hips Road.

- Graves, Milford. (2010) "Music Extensions of Infinite Dimensions." In Arcana V: Music, Magic and Mysticism ed. John Zorn, 171-186. New York, Hips Road.

- Graves, Milford and Pullen, Don. (January 1967) "Black Music." In Liberator, 20.

- Graves, Milford. (1968) "Untitled." In The Cricket Vol. 1, 14-17.

- Graves, Milford. (1969) "Music Workshop." In The Cricket Vol. 3, 17-19.

- Graves, Milford. (1969) "Black Music: New Revolutionary Art." In Black Arts: An Anthology of Black Creations ed. Ahmed Alhamisi, 40-41. Detroit, Black Arts Publications.

References

- Erlewine, Michael; Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Yanow, Scott, eds. (1996). All Music Guide to Jazz (2nd ed.). Miller Freeman. p. 309.

- "Milford Graves: Biography". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 220.

- "Milford Graves: Faculty Emeritus". Bennington.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Litweiler, John (1984). The Freedom Principle:Jazz after 1958. Da Capo. p. 137.

- Jacobson, Mark (November 12, 2001). "The Jazz Scientist". New York Magazine.

- "Milford Graves: Heart Music". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Cox, Christoph (March 2018). "Matters of the Heart: Christoph Cox on Milford Graves". ArtForum.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Milford Graves: Hand-Painted Album Art". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Milford Graves". QueensMuseum.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Milford Graves: Queens Museum". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Bengal, Rebecca. "Some Plant Stuff, Man: Tending the Global Garden with Milford Graves". HaomaEarth.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Milford Graves: Garden". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Russonello, Giovanni (April 26, 2018). "For Milford Graves, Jazz Innovation Is Only Part of the Alchemy". NYTimes.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Milford Graves on Yara". MilfordGraves.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Co-founder: Milford Graves". Élpiséremo.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Kilgannon, Corey (November 9, 2004). "Finding Healing Music in the Heart". NYTimes.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 220.

- Licht, Alan (March 2018). "Listen to your Heart" (PDF). The Wire. p. 34. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Corbett, John (2015). Microgroove: Forays Into Other Music. Duke University Press. p. 74.

- Mittal, Aakash (February 1, 2018). "Milford Graves: Sounding the Universe". NewMusicUSA.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Medwin, Marc (June 22, 2009). "Milford Graves: Time Piece". AllAboutJazz.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Licht, Alan (March 2018). "Listen to your Heart" (PDF). The Wire. p. 35. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Licht, Alan (March 2018). "Listen To Your Heart" (PDF). The Wire. p. 35. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 222.

- Licht, Alan (March 2018). "Listen To Your Heart" (PDF). The Wire. p. 40. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Toop, David (2016). Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation and the Dream of Freedom Before 1970. Bloomsbury. p. 270.

- Jenkins, Todd (2004). Free Jazz and Free Improvisation: An Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 163.

- AAJ Staff (April 30, 2003). "A Fireside Chat with Milford Graves". AllAboutJazz.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 223.

- Shteamer, Hank (June 2015). "Interview: NYC percussion legend Milford Graves". MusicAndLiterature.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Porter, Lewis; DeVito, Chris; Fujioka, Yasuhiro; Wild, David; Schmaler, Wolf (2008). The John Coltrane Reference. Routledge. p. 770.

- Laskey, Kevin (July 13, 2017). "Signifyin(g) with the Dead: Musical memorialization at John Coltrane's Funeral". MusicAndLiterature.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Giddins, Gary (2008). Natural Selection: Gary Giddins on Comedy, Film, Music, and Books. Oxford University Press. p. 286.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. pp. 228–229.

- Anderson, Iain (2007). This Is Our Music: Free Jazz, the Sixties, and American Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 165.

- Watson, Ben (2013). Derek Bailey and the Story of Free Improvisation. Verso.

- Sprague, David (June 16, 1999). "Sonic Youth/New York Art Quartet". Variety. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Davis, Francis (June 13, 1999). "MUSIC; 60's Free Jazz for the Sonic Youth Crowd". New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Milford Graves & Shahzad Ismaily". IssueProjectRoom.org. September 6, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Clarke, Cath (August 30, 2018). "Milford Graves Full Mantis review – cutting-edge drums and terrific storytelling". The Guardian.

- Margasak, Peter (Winter 2019). "CMA Duos: Milford Graves and Jason Moran". Chamber-Music.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Christopher, Michael (August 13, 2013). "Interview: William DuVall of Alice In Chains on getting out of the box, moving forward, and respecting a legacy". Vanyaland.

- "Milford Graves". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "2015 Doris Duke Impact Awards". Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Toop, David (2016). Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation and the Dream of Freedom Before 1970. Bloomsbury. p. 272.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 223.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. p. 226.

- Szwed, John (2013). "The Antiquity of the Avant-Garde: A Meditation on a Comment by Duke Ellington". In Heble, Ajay; Wallace, Rob (eds.). People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz is Now!. Duke University Press. p. 54.

- Wilmer, Val (2018). As Serious As Your Life. Serpent's Tail. pp. 225–226.

- Corbett, John (2015). Microgroove: Forays Into Other Music. Duke University Press. p. 75.

- Mittal, Aakash (January 9, 2018). "Milford Graves". BombMagazine.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Burwell, Paul (Summer 1981). "Bäbi Music". Collusion. No. 1. p. 33.

- Corey Kilgannon, "Finding Healing Music in the Heart", New York Times, November 9, 2004 Retrieved November 20, 2004

- Dayal, Geeta (March 19, 2018). "Milford Graves: Full Mantis". 4 Columns.

- "Patents by Inventor Milford Graves". Justia Patents.

External links

- Audio Recordings of WCUW Jazz Festivals - Jazz History Database

- Milford Graves discography on Mindspring.com

- 13 episodes of Milford Graves talking on ImprovLive 365 from 2012 (via YouTube)

- Milford Graves interview at All About Jazz

- Milford Graves interview at Bomb

- Milford Graves interview at NewMusicBox

- Milford Graves interview at Point of Departure

- Article on Milford Graves: Full Mantis documentary at Independencia