Mildew

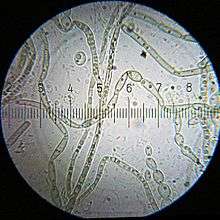

Mildew is a form of fungus. It is distinguished from its closely related counterpart, mould, largely by its colour: moulds appear in shades of black, blue, red, and green, whereas mildew is white. It appears as a thin, superficial growth consisting of minute hyphae (fungal filaments) produced especially on living plants or organic matter such as wood, paper or leather.[1][2] Both mould and mildew produce distinct offensive odors, and both have been identified as the cause of certain human ailments.

In horticulture, mildew is either species of fungus in the order Erysiphales, or fungus-like organisms in the family Peronosporaceae. It is also used more generally to mean mould growth. In Old English, mildew meant honeydew (a substance secreted by aphids on leaves, formerly thought to distill from the air like dew), and later came to mean mould or fungus.[3]

Plant pathogens

What horticulturalists and gardeners often refer to as mildew is more precisely powdery mildew. It is caused by many different species of fungi in the order Erysiphales. Most species are specific to a narrow range of hosts, and all are obligate parasites of flowering plants. The species that affects roses is Sphaerotheca pannosa var. rosae.

Another plant-associated type of mildew is downy mildew, caused by fungus-like organisms in the family Peronosporaceae (Oomycota). They are obligate plant pathogens, and the many species are each parasitic on a narrow range of hosts. In agriculture, downy mildews are a particular problem for potato, grape, tobacco and cucurbits farmers.

Household varieties

The term mildew is often used generically to refer to mould growth, usually with a flat growth habit. Moulds can thrive on many organic materials, including clothing, leather, paper, and the ceilings, walls and floors of homes or offices with poor moisture control. Mildew can be cleaned using specialised mildew remover, or substances such as bleach (though they may discolour the surface).[4]

There are many species of mould. The black mould which grows in attics, on window sills, and other places where moisture levels are moderate often is Cladosporium. Colour alone is not always a reliable indicator of the species of mould. Proper identification requires a microbiologist or mycologist. Mould growth found on cellulose-based substrates or materials where moisture levels are high (90 percent or greater) is often Stachybotrys chartarum. “Black mould,” also known as "toxic black mould", properly refers to S. chartarum. This species is commonly found indoors on wet materials containing cellulose, such as wallboard (drywall), jute, wicker, straw baskets, and other paper materials. S. chartarum does not, however, grow on plastic, vinyl, concrete, glass, ceramic tile, or metals. A variety of other mould species, such as Penicillium or Aspergillus, may appear to grow on non-cellulosic surfaces but are actually growing on the bio-film that adheres to these surfaces. Glass, plastic, and concrete provide no food for organic growth and as such cannot support mould or mildew growth alone without bio-film present. In places with stagnant air, such as basements, moulds can produce a strong musty odour.

The pink "mildew" often found on plastic shower curtains and bathroom tile is actually a red yeast, Rhodotorula.

Environmental conditions

Mildew requires certain factors to develop. Without any one of these, it cannot reproduce and grow. The requirements are a food source (any organic material), sufficient ambient moisture (a relative humidity of between 62 and 93 percent), and reasonable warmth (77 °F (25 °C) to 88 °F (31 °C) is optimal, but some growth can occur anywhere between freezing and 95 °F (35 °C)). Slightly acidic conditions are also preferred.[5] At warmer temperatures, air is able to hold a greater volume of water; as air temperatures drop, so does the ability of air to hold moisture, which then tends to condense on cool surfaces. This can work to bring moisture onto surfaces where mildew is then likely to grow (such as an exterior wall).

Preventing the growth of mildew therefore requires a balance between moisture and temperature. This can be achieved by minimising the moisture available in the air

Air temperatures at or below 70 °F (21 °C) will inhibit growth, but only if the relative humidity is low enough to prevent water condensation (i.e., the dew point is not reached.

With warmer temperatures, the water holding capacity of the air increases.[6]:6 This means that if the amount of water vapour in the warming air remains the same, the air will become drier, i.e., it has a lower relative humidity). This again inhibits fungal growth. Warm, growth-favouring temperatures coupled with high relative humidity, however, will set the stage for mildew growth.

Air conditioners are one effective tool for removing moisture and heat from otherwise humid warm air. The coils of an air conditioner cause moisture in the air to condense on them, eventually losing this excess moisture through a drain and placing it back into the environment. They can also inhibit mildew growth by lowering indoor temperatures. In order for them to be effective, air conditioners must recirculate the existing indoor air and not be exposed to warm, humid outside air. Some energy efficient air conditioners may cool a room so quickly that they do not have an opportunity to also effectively collect and drain significant ambient water vapour.[5]

References

- "Mildew". Compact Oxford English Dictionary.

- "Mildew". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary (11th ed.).

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 1969, entry "mecnlit-" in Appendix

- "Cleaning Mildew from Retractable Awnings". Shade & Privacy. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Peart, Virginia (October 2001), How to prevent and remove mildew (PDF), University of Florida IFAS Extension, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-19

- Florian, Mary-Lou (1997). Heritage Eaters – Insects & Fungi in Heritage Collections. London: James & James. ISBN 1873936494.