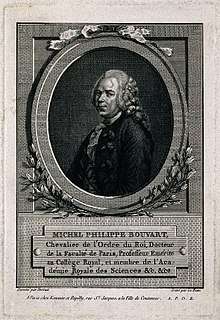

Michel-Philippe Bouvart

Michel-Philippe Bouvart (Chartres, 11 January 1717 – Paris, 19 January 1787) was a French medical doctor.

Michel-Philippe Bouvart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 11, 1717 |

| Died | January 19, 1787 (aged 70) Paris |

| Nationality | France |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Years active | 1730-1783 |

| Known for | Witticisms |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | French Academy of Sciences, Collège Royal, Paris Faculty of Medicine |

| Awards | Order of St. Michael |

He was made a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1743 and a professor in the Paris Faculty of Medicine in 1745 and also in the Collège Royal in 1745, where he took the medical chair previously held by Pierre-Jean Burette. Louis XV granted him letters of nobility and the Order of St. Michael in 1768 or 1769.[1][2]

Bouvart was famous for his quick diagnoses and accurate prognoses, but also for his caustic wit[3] and polemical writing against his fellow physicians, notably Théodore Tronchin, Théophile de Bordeu, Exupère Joseph Bertin, Antoine Petit. He was opposed to inoculation against smallpox. He championed Virginia polygala or Seneka as a remedy for snakebite.[2][4]

Although he was able and learned, he is perhaps best known for his witticisms.[5]

Witticisms

We know that, in Paris, fashion imposes its dictates on medicine just as it does with everything else. Well, at one time, pyramidal elm bark[6] had a great reputation; it was taken as a powder, as an extract, as an elixir, even in baths. It was good for the nerves, the chest, the stomach — what can I say? — it was a true panacea. At the peak of the fad, one of Bouvard’s [sic] patients asked him if it might not be a good idea to take some: "Take it, Madame", he replied, "and hurry up while it [still] cures." [dépêchez-vous pendant qu’elle guérit]

Une dame consulta Bouvard [sic] sur le desir qu'elle avoit d'user un remède alors à la mode. Hâtez-vous de le prendre pendant qu'il guérit, lui répondit le caustique docteur.

A lady consulted Bouvart about her wish to use a remedy which was then fashionable. "Rush to take it while it [still] cures", replied the acerbic doctor.

— Anthelme Richerand, 1812[7]

Variants of Bouvart's quip about the placebo effect of using a new treatment or medicine "while it still works" are often quoted without crediting him.

It is said that he replied to Cardinal ***, a not very regular prelate (some say Abbot Terray), who was complaining of suffering like a damned person: "What! Already, monseigneur?" In my opinion, he might well have said this about one of his patients, but not to his face; manners would not allow that.

— Gaston de Lévis, 1813[5]

A "regular prelate" (prélat régulier) is a high-ranking churchman; this is a play on words, implying that he was irregular, that is, immoral. Abbot Terray is Joseph Marie Terray.

Mr. *** was being tried for a dishonorable matter; he got sick, and died. Bouvard [sic] was his doctor, and said: I got him off the hook. It was said of the same person: He is truly sick, he can't take any more [presumably medicine].

— Antoine-Denis Bailly, 1803[8]

Bouvart went to see one of the lords of the old Court, who was seriously ill for a fortnight. As he entered, Good day, Mr. Bouvart, said the patient. I am happy to see you. I feel much better; I think I no longer have a fever. Look! — I am certain of it, says the doctor; I noticed it at your first word. — How is that? — Oh! Nothing simpler. In the first days of your illness, and as long as you were in danger, I was your dear friend; you called me nothing else. The last time, when you were somewhat better, I was just your dear Bouvart. Today, I am Mr. Bouvart. It is clear that you are cured.

— L'esprit des journaux, 1794[3]

This story has been compared to Euricius Cordus's epigram:

Three faces wears the doctor; when first sought

An angel's--and a god's the cure half wrought

But when that cure complete, he seeks his fee,

The devil looks less terrible than he.— Cordus, circa 1520[9]

Early life

Bouvart's father Claude was a physician.[1] Michel-Philippe received his medical degree in Reims in 1730 and practiced in Chartres. In 1736, he left for Paris.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Michel-Philippe Bouvart |

Bibliography

- Antoine Jean Baptiste Maclou Guenet, Éloge historique de Michel-Philippe Bouvart, chez Quillau, Paris, 1787 full text

- Nicolas de Condorcet, Éloge de M. Bouvart, dans Éloges des académiciens de l'Académie royale des sciences, morts depuis l'an 1783, chez Frédéric Vieweg, Brunswick et Paris, 1799, p. 270-307 full text

- Dezobry et Bachelet, Dictionnaire de biographie 1 Delagrave, 1876, p. 359

- Jean Baptiste Glaire, vicomte Joseph-Alexis Walsh, Joseph Chantrel, Encyclopédie catholique, 1842 full text.

- Bibliothèque chartraine, dans Mémoires de la Société archéologique de l'Orléanais 19:51-53, 1883 full text

Notes

- Guénet, Eloge historique

- Hugh James Rose, A New General Biographical Dictionary, 1848 4:484, s.v.

- L'esprit des journaux, françois et étrangers 23:2:74-75 (February 1794)

- Alexander Chalmers, The General Biographical Dictionary etc., 6:247

- Gaston de Lévis, Souvenirs et portraits, 1780-1789, 1813, p. 240

- the inner bark of Ulmus campestris: Simon Morelot, Cours élémentaire d'histoire naturelle pharmaceutique..., 1800, p. 349 "the elm, pompously named pyramidal...it had an ephemeral reputation"; Georges Dujardin-Beaumetz, Formulaire pratique de thérapeutique et de pharmacologie, 1893, p. 260

- Anthelme Richerand, Des erreurs populaires relatives à la médecine, p. 206 (footnote)

- Antoine-Denis Bailly, Choix d'anecdotes, anciennes et modernes, recueillies des meilleurs auteurs, 5, 2nd ed., 1803 (Year XI) p. 15

- "Anecdote", The Lancet, 3:256, May 22, 1824