Menstrual psychosis

Menstrual psychosis is a term describing a periodic psychosis with acute onset in a particular phase of the menstrual cycle. Most psychiatrists are skeptical that the symptoms indicate a distinct disorder.[3] Over the last few decades some case studies have been published in medical literature with an accompanying argument that the condition is under recognized by practicing psychiatrists.[4]

| Menstrual psychosis | |

|---|---|

| |

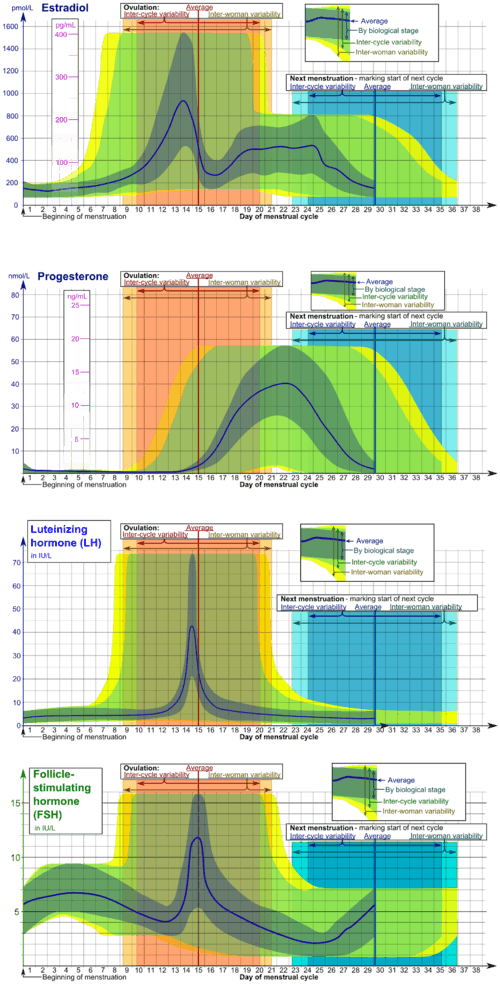

| Image showing hormonal changes during mestruation,main trigger of the disorder | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Hallucinations, delusions, stupor, confusion, mania[1] |

| Complications | Suicide |

| Causes | Hormonal changes |

| Risk factors | History of other psychotic disorders (eg.schizophrenia, bipolar disorder),[2] unknown, epilepsy, endometriosis |

| Differential diagnosis | Schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, premenstrual dysphoric syndrome |

| Treatment | Medication, cognitive behavioral therapy |

| Medication | Anti-psychotics |

Definition

Menstrual psychosis is a rare form of severe mental illness. Episodes have a sudden onset in a previously asymptomatic person, and are usually of brief duration, with full recovery. The psychotic symptoms can include confusion or hallucinations, mutism and stupor, delusions, or a manic syndrome; these are distinct from premenstrual dysphoric disorder. These episodes occur in rhythm with the menstrual cycle.

Clinical features and nosology

Most of these patients have evidence of bipolar disorder.[5] Many have manic and depressive phases, recurrent mania or schizoaffective mania. A minority have atypical forms, such as catatonia, extreme anxiety associated with delusions or hallucinations, or cycloid (acute polymorphic) features. Thus, the clinical features resemble those of the common form of postpartum psychosis, and (like this form of puerperal psychosis) menstrual psychosis is not a ‘disease in its own right’, but a part of the bipolar spectrum; one of the reasons for its scientific interest is the insight it might give into the triggers of episodes in women with the bipolar diathesis.

There is evidence of two triggers – at the mid-cycle associated with ovulation, and in the late luteal phase (necrotic phase).[6]

As in the postpartum group of psychoses, a minority of cases have organic causes, associated with epilepsy,[7] urea cycle disorders[8][9] and cerebral endometriosis.[10] Cases associated with learning difficulties and early infantile autism have also been reported.[11]

Onset and Course

About two thirds of cases start in the second decade,[12] and it is of great interest that 30 cases have had their first episode before the menarche,[13] a phenomenon has also been seen in three medical disorders – diabetes,[14] epilepsy[15] and hypersomnia[16] – and in migraine psychosis.[17] Another epoch of increased susceptibility is the postpartum period, at the restart of the menstrual cycle after childbirth.[18] An established pattern of menstrual episodes has also continued, month by month, during a phase of amenorrhoea; occasional patients have experienced monthly psychoses only during amenorrhoea.[19] Two patients have developed, or continued, periodic episodes after the destruction of the pituitary gland.[20][21]

In most patients, menstrual psychosis is a self-limiting disorder, affecting only a small proportion of the 400 menstrual cycles in a woman’s life.[22] Since menstruation is one of many triggers of bipolar episodes, it is not surprising that some women, at other times of their lives, suffer manic phases, or a chaotic bipolar illness, without a menstrual link.

Investigation and treatment

It is essential that the diagnosis is firmly established by the precise dating of episodes and the menses.[23] Two cycles of prospective daily ratings (standard for the diagnosis of menstrual mood disorder[24]) are not appropriate; a daily narrative diary is the best method of establishing the temporal pattern. Because the correction of abnormal menstruation may be important in treatment,[25] it is recommended to obtain a gynaecological opinion.

Once a baseline has been established, the pattern of monthly relapses offers an opportunity for single-patient sequential trials seeking a bespoke therapy for the patient. Conventional neuroleptic or mood-stabilising agents are appropriate to control episodes, if prolonged, but seem ineffective in preventing periodic recurrences. This is the therapeutic challenge. There have been no therapeutic trials, but success has been claimed with unconventional treatments, including clomifene, thyroid and progesterone;[26] the concept of menstrual psychosis is useful in directing sufferers to these treatments, which are not commonly used in psychiatry.

Cause

A family history of mental illness is common. There is an association with abnormal menstruation, such as amenorrhoea, anovulatory cycles[27] or luteal phase defects.[28] There is much evidence of a close relationship to childbearing psychoses.[29]

The occurrence of episodes before the menarche, during amenorrhoea, and after destruction or removal of the ovaries and pituitary, together with periodic monthly cases in men,[30] all suggest the involvement of the hypothalamic nucleus governing the menstrual cycle – the neuronal complex that produces gonadotropin releasing hormone.[31]

History

The first indications of abnormal behaviour linked to the menses were two reports[32][33] in the same early French journal: one described a paroxysmal ‘’délire’’, which was at its height when the menses were expected, but suppressed; and the other described monthly attacks of demonic possession. Adequate description of menstrual psychosis had to wait almost 100 years until a thesis written in 1848:[34] it reported a patient with 13 episodes, starting with the menarche. In 1851 Brière de Boisment[35] described four cases. The second half of the 19th century was the heyday of publications on this subject, including Ellen Powers’ thesis,[36] Icard’s monograph,[37] Wollenberg’s description of mid-cycle psychosis,[38] and the accounts by Schönthal [39] and Friedmann [40] of episodes starting before the menarche. This productive period came to an end with the publication, in the year of his death (1902), of v. Krafft Ebing’s Psychosis Menstrualis.[41] Since then only one new variant has been described – Runge’s periodic psychosis during pregnancy.[42] Many of the papers were French or German, but in the mid-20th century, Japanese clinicians began to publish extensive studies. In 2008 a monograph[43] reviewed over 1,000 works, identifying 80 cases with substantial evidence and setting out the principles of the clinical study of this disorder. In 2017, a second monograph[44] revised this analysis, identifying 119 cases with at least five dated episodes. The trickle of case reports continues unabated from all over the world - more than 35 possible cases since 2000.

Menstruation and other mental disorders

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

This is the name given to a severe form of the premenstrual syndrome; its synonyms include premenstrual tension, late luteal phase dysphoric disorder and menstrual mood disorder. It is a common disorder – two orders of magnitude more common than menstrual psychosis. The present evidence suggests that it is distinct from menstrual psychosis.[45] Premenstrual dysphoric disorder has different symptoms (irritability and tension being the most characteristic), is defined by its luteal timing, responds to SSRIs and is not strongly associated with abnormal menstruation; indeed it may only occur in normal cycles.[46] Menstrual psychosis is defined by various psychotic symptoms, may occur at the mid-cycle and during menstrual bleeding, is associated with anovulation and other menstrual disorders, and probably responds to the induction of ovulation.

Bipolar disorder

Premenstrual exacerbation is the triggering or worsening of otherwise defined conditions during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle; it may be a clinical marker predicting a more symptomatic and relapse-prone phenotype in reproductive-age women with bipolar disorder. Bipolar women with premenstrual exacerbation have been found to have more episodes (primarily depressive) than those without, but are not more likely to meet criteria for rapid cycling.[47] Rapid cycling has a female preponderance, and occurs with greater frequency premenstrually, at the puerperium and at the menopause. While the symptom of rapid cycling is typically associated with bipolar disorder, there are a number of other conditions which also precipitate very rapid cycling between moods (emotional lability), including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, other endocrine issues, sleep disorders, borderline personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, acquired brain injury and substance abuse. Mood stabilizers are often used to address these effects.[48]

The existence of menstrual psychosis means that some bipolar women, at a certain time in their lives (most commonly adolescence), are extremely and exclusively prone to the provocation of episodes by menstruation. One might expect, therefore, a general relationship between menstruation and manic depression, with many sufferers experiencing mild menstrual episodes in addition to those provoked by other triggers. But this does not seem to be true; on the whole no general association has been demonstrated. Instead, studies have shown that a subgroup of bipolar women experience a menstrual effect.[49] Three small studies have shown that 5/47,[50] 8/25[51] and 13/41[52] were susceptible. They agree that the majority experience no effect of the menses, and therefore no susceptibility to the menstrual trigger(s).

Schizophrenia

The meaning of the term ‘schizophrenia’ has varied from time to time and country to country, but it is now reserved for chronic psychoses with symptoms like auditory hallucinations, delusions of control and other bizarre delusions, and ‘negative symptoms’ such as incongruous affect.[53] Admission of women to psychiatric hospitals is increased by about 50% in the last few premenstrual days and during menstrual bleeding;[54][55][56] most of these women had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. There is evidence that the serum level of oestrogens is correlated with symptom severity.[57][58][59]

Menstruation is controlled by the hypothalamic gonadorelin neuronal complex, via the pituitary and ovaries; the interaction between the menstrual cycle and schizophrenia could be at any of these levels, but there is support for the role of oestrogens. Oestrogens, among their many cerebral effects, have actions on dopaminergic receptors similar to neuroleptic agents.[60][61] Oestrogen levels are high in the mid-luteal phase and fall shortly before menstrual bleeding,[62] coinciding with the increase of symptoms and hospitalization in the perimenstrual phase. This hypothesis is supported by a relative dearth of new onsets of schizophrenia in younger women, with a second peak after the mid-forties,[63] and by the milder severity and better anti-psychotic treatment response in female patients.[61] Several randomised controlled trials have shown that oestrogens augment the action of antipsychotic agents.[64]

Menstruation and brain diseases

A number of medical and surgical diseases are affected by the menstrual cycle.[65][66] The best established are allergies to progesterone and oestrogen, asthma, diabetes mellitus, endometriosis, migraine, porphyria and (among the brain disorders) epilepsy and hypersomnia, which will be summarized here.

Catamenial epilepsy

It is known that the menstrual cycle has a modest effect on the frequency of seizures in epileptic women.[67] There are three patterns – a paramenstrual increase (from two days before to three days after the onset of menstrual bleeding), during ovulation and throughout the whole luteal phase in anovulatory cycles.[68] One of the reasons why the menstrual cycle has this effect is that progesterone and its metabolites, especially allopregnanolone, are ligands of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors, and resemble benzodiazepines in their anticonvulsant actions; oestrogens have the opposite effect.[69] Natural progesterone has been shown to be effective in reducing seizures in the paramenstrual group.[70] Other forms of catamenial epilepsy may benefit from suppression of the menstrual cycle.[71] As mentioned above, cyclical epilepsy has been reported before the menarche.

Citations

- Vengadavaradan, Ashvini; Sathyanarayanan, Gopinath; Kuppili, Pooja Patnaik; Bharadwaj, Balaji (2018). "Is menstrual Psychosis a Forgotten Entity?". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 40 (6): 574–576. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_205_18 (inactive 27 June 2020). PMC 6241186. PMID 30533955.

- Reilly, Thomas J; Sagnay de la Bastida, Vanessa C; Joyce, Dan W; Cullen, Alexis E; McGuire, Philip (January 2020). "Exacerbation of Psychosis During the Perimenstrual Phase of the Menstrual Cycle: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (1): 78–90. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz030. PMC 6942155. PMID 31071226.

- BROCKINGTON, IAN (February 2005). "Menstrual psychosis". World Psychiatry. 4 (1): 9–17. ISSN 1723-8617. PMC 1414712. PMID 16633495.

- Vengadavaradan, Ashvini; Sathyanarayanan, Gopinath; Kuppili, Pooja Patnaik; Bharadwaj, Balaji (2018). "Is menstrual Psychosis a Forgotten Entity?". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 40 (6): 574–576. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_205_18 (inactive 27 June 2020). ISSN 0253-7176. PMC 6241186. PMID 30533955.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 333–334.

- Brockington 2017, p. 304.

- Kramer, Michael S. (1 March 1977). "Menstrual Epileptoid Psychosis in an Adolescent Girl". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 131 (3): 316–317. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120160070012. PMID 842518.

- Grody, W. W.; Chang, R. J.; Panagiotis, N. M.; Matz, D.; Cederbaum, S. D. (1994). "Menstrual cycle and gonadal steroid effects on symptomatic hyperammonaemia of urea-cycle-based and idiopathic aetiologies". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 17 (5): 566–574. doi:10.1007/BF00711592. PMID 7837763. S2CID 26389532.

- Wakutani, Y; Nakayasu, H; Takeshima, T; Mori, N; Kobayashi, K; Endo, F; Nakashima, K (November 2001). "A case of late-onset carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I deficiency, presenting periodic psychotic episodes coinciding with menstrual periods". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology. 41 (11): 780–5. PMID 12080609.

- Berkley, Henry J. (January 1900). "Transitory alienation following distressing pain". American Journal of Psychiatry. 56 (3): 515–521. doi:10.1176/ajp.56.3.515.

- Brockington 2017, p. 337.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 335–336.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 310–313.

- Brown, K G; Darby, C W; Ng, S H (November 1991). "Cyclical disturbance of diabetic control in girls before the menarche". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 66 (11): 1279–1281. doi:10.1136/adc.66.11.1279. PMC 1793290. PMID 1755637.

- Muskens, J (1926). Epilepsie, vergleichende Pathogenese, Erscheinungen, Behandlung [Epilepsy, comparative pathogenesis, symptoms, treatment] (in German). Berlin: Springer. pp. 203–206. OCLC 15269360.

- Sugimoto, T; Ota, T; Suzukawa, Y; Nishida, N; Yasuhara, A (May 1991). "[A case of periodic hypersomnia: the effect of Tokishakuyakusan]". No to Hattatsu = Brain and Development (in Japanese). 23 (3): 303–5. PMID 2043375.

- Ulrich M (1912) Beiträge zur Ätiologie und zur klinischen Stellung der Migräne. Monatsschrift für Psychiatrie und Neurologie 31 (ergänzungsheft): 194-195.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 321–327.

- Naumoff, F. A. (December 1929). "Eine eigenartige Psychose im Zusammenhang mit einer Funktionsstörung des endokrinen Systems" [A strange psychosis related to an endocrine system dysfunction]. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten (in German). 88 (1): 226–233. doi:10.1007/BF01814136. S2CID 39732351.

- Yamashita, Itaru (1993). Periodic psychosis of adolescence. Hokkaido University Press. pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-4-8329-0281-7. OCLC 30864100.

- Danziger, L; Kindwall, JA; Lewis, HR (November 1948). "Periodic relapsing catatonia; simplified diagnosis and treatment". Diseases of the Nervous System. 9 (11): 330–5. PMID 18892896.

- Brockington 2017, p. 336.

- Brockington 2017, p. 341.

- Moos, Rudolf H. (November 1968). "The Development of a Menstrual Distress Questionnaire". Psychosomatic Medicine. 30 (6): 853–867. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.522.3998. doi:10.1097/00006842-196811000-00006. PMID 5749738. S2CID 30273870.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 336–337.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 342–344.

- Hatotani, N; Ishida, C; Yura, R; Maeda, M (20 December 1960). "Endocrinological studies on the periodic psychoses". Folia Psychiatrica et Neurologica Japonica. Suppl 6: 95–106. PMID 13712249.

- Okuyama, T (1982). "[A case of premenstrual tension syndrome associated with psychotic episodes--on the endocrinological dynamics]". Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi = Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica (in Japanese). 84 (12): 939–46. PMID 6892129.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 320–330.

- Brockington 2017, p. 319.

- Gore, Andrea C. (2002). GnRH: The Master Molecule of Reproduction. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-7923-7681-1.

- Nicolau, M (1758). "Observation sur une mélancholie erotico-hystérique, accompagnée de convulsions, de délire convulsif, et du dérangement général de toutes les fonctions" [Observation of an erotic-hysterical melancholy, accompanied by convulsions, convulsive delirium, and the general disturbance of all functions]. Journal de Vandermonde (in French). 9: 114–132.

- Desmilleville (1759). "Observation addressée à M. Vandermonde, sur une fille que l'on croyoit possédée" [Observation addressed to Mr. Vandermonde, on a girl which one believed to have possessed]. Journal de Médécine et de Chirurgie (in French). 10: 408–415.

- Barbier, Michel-Victor (1849). De l'influence de la mentruation sur les maladies mentales [The influence of mentruation on mental illnesses] (Thesis) (in French). OCLC 50297243.

- Brière de Boismont, A (1851). "Recherches bibliographiques et cliniques sur la folie puerpérale, precedées d'un aperçu sur les rapports de la menstruation et de l'aliénation mentale" [Bibliographic and clinical research on puerperal madness, preceded by an overview on the reports of menstruation and insanity]. Annales Médico-psychologiques (in French). 3: 574–610.

- Powers, Ellen F (1883). Beitrag zur Kenntniss der menstrualen Psychosen [Contribution to the knowledge of menstrual psychoses] (Thesis) (in German). OCLC 67072696.

- Icard S (1889) Contribution à l'étude de l’état psychique de la femme pendant la période menstruelle, considéré plus spécialement dans ses rapports avec le morale et la médécine légal. This Parisian thesis was also published in 1890 as a book, La Femme pendant la Période Menstruelle: Étude de Psychologie Morbide et de Médécine Légale, Paris, Alcan.

- Wollenberg R (1891) Drei Fälle von periodisch auftretender Geistesstörung. Charité-Annalen 16: 427-476.

- Schönthal (1892) Beiträge zur Kenntnis der in frühem Lebensalter Psychosen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 23: 816-833.

- Friedmann M (1894) Über die primordiale menstruelle Psychose. Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 41: 4-7, 27-31, 50-53 & 69-71.

- Krafft-Ebing, R. v (1902). Psychosis menstrualis: eine klinisch-forensische Studie [Psychosis menstrualis: a clinical-forensic study] (in German). Ferdinand Enke. OCLC 11333791.

- Runge, W. (June 1911). "Die Generationspsychosen des Weibes" [The generation psychoses of women]. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten (in German). 48 (2): 545–690. doi:10.1007/BF01821223. S2CID 6832316.

- Brockington, I. F (2008). Menstrual psychosis and the catamenial process. Eyry Press. ISBN 978-0-9540633-5-1. OCLC 315950413.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 279–372.

- Brockington, I. F (2008). Menstrual psychosis and the catamenial process. Eyry Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-0-9540633-5-1. OCLC 315950413.

- Hammarbäk, Stefan; Ekholm, Ulla-Britt; Bäckström, Torbjörn (August 1991). "Spontaneous anovulation causing disappearance of cyclical symptoms in women with the premenstrual syndrome". Acta Endocrinologica. 125 (2): 132–137. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1250132. PMID 1897330.

- Dias, Rodrigo S.; Lafer, Beny; Russo, Cibele; Del Debbio, Alessandro; Nierenberg, Andrew A.; Sachs, Gary S.; Joffe, Hadine (April 2011). "Longitudinal Follow-Up of Bipolar Disorder in Women With Premenstrual Exacerbation: Findings From STEP-BD". American Journal of Psychiatry. 168 (4): 386–394. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121816. PMID 21324951.

- Goldberg, Joseph (December 2011). "Ultra-rapid cycling bipolar disorder: A critical look". Current Psychiatry. 10 (12): 42–55.

- Teatero, Missy L; Mazmanian, Dwight; Sharma, Verinder (February 2014). "Effects of the menstrual cycle on bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 16 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1111/bdi.12138. PMID 24467469.

- Wehr, TA; Sack, DA; Rosenthal, NE; Cowdry, RW (February 1988). "Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients". American Journal of Psychiatry. 145 (2): 179–184. doi:10.1176/ajp.145.2.179. PMID 3341463.

- Leibenluft, E (February 1996). "Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues". American Journal of Psychiatry. 153 (2): 163–173. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.2.163. PMID 8561195.

- Shivakumar, Geetha; Bernstein, Ira H.; Suppes, Trisha; Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network; Keck, PE; McElroy, SL; Altshuler, LL; Frye, MA; Nolen, WA; Kupka, RW; Grunze, H; Leverich, GS; Mintz, J; Post, RM (April 2008). "Are Bipolar Mood Symptoms Affected by the Phase of the Menstrual Cycle?". Journal of Women's Health. 17 (3): 473–478. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0466. PMID 18328012.

- World Health Organization (1992). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 86–87.

- Bergemann, N.; Parzer, P.; Nagl, I.; Salbach, B.; Runnebaum, B.; Mundt, Ch.; Resch, F. (1 November 2002). "Acute psychiatric admission and menstrual cycle phase in women with schizophrenia". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 5 (3): 119–126. doi:10.1007/s00737-002-0004-2. PMID 12510215.

- Herceg, Miroslav; Puljić, Krešimir; Sisek-Šprem, Mirna; Herceg, Dora (2018). "Influence of hormonal status and menstrual cycle phase on psychopatology in acute admitted patients with schizophrenia" (PDF). Psychiatria Danubina. 30 (Suppl 4): 175–179. PMID 29864756.

- Reilly, Thomas J; Sagnay de la Bastida, Vanessa C; Joyce, Dan W; Cullen, Alexis E; McGuire, Philip (2020). "Exacerbation of Psychosis During the Perimenstrual Phase of the Menstrual Cycle: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (1): 78–90. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz030. PMC 6942155. PMID 31071226.

- Riecher-Rossler, A.; Hafner, H.; Stumbaum, M.; Maurer, K.; Schmidt, R. (1 January 1994). "Can Estradiol Modulate Schizophrenic Symptomatology?". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 20 (1): 203–214. doi:10.1093/schbul/20.1.203. PMID 8197416.

- Bergemann, Niels; Parzer, Peter; Runnebaum, Benno; Resch, Franz; Mundt, Christoph (24 April 2007). "Estrogen, menstrual cycle phases, and psychopathology in women suffering from schizophrenia". Psychological Medicine. 37 (10): 1427–1436. doi:10.1017/S0033291707000578. PMID 17451629.

- Seeman, M. V. (May 2012). "Menstrual exacerbation of schizophrenia symptoms". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 125 (5): 363–371. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01822.x. PMID 22235755.

- McEwen, B S; Davis, P G; Parsons, B; Pfaff, D W (March 1979). "The Brain as a Target for Steroid Hormone Action". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2 (1): 65–112. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.02.030179.000433. PMID 395885.

- Gogos, Andrea; Sbisa, Alyssa M.; Sun, Jeehae; Gibbons, Andrew; Udawela, Madhara; Dean, Brian (2015). "A Role for Estrogen in Schizophrenia: Clinical and Preclinical Findings". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2015: 615356. doi:10.1155/2015/615356. PMC 4600562. PMID 26491441.

- Reed, Beverly G.; Carr, Bruce R. (2000). "The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation". Endotext. MDText. PMID 25905282.

- Grigoriadis, Sophie; Seeman, Mary V (24 June 2016). "The Role of Estrogen in Schizophrenia: Implications for Schizophrenia Practice Guidelines for Women". The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 47 (5): 437–442. doi:10.1177/070674370204700504. PMID 12085678.

- Begemann, Marieke J.H.; Dekker, Caroline F.; van Lunenburg, Mari; Sommer, Iris E. (November 2012). "Estrogen augmentation in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of current evidence". Schizophrenia Research. 141 (2–3): 179–184. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.016. PMID 22998932. S2CID 40584474.

- Case, Allison M.; Reid, Robert L. (13 July 1998). "Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Medical Disorders". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (13): 1405–12. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.13.1405. PMID 9665348.

- Bäckström, Torbjörn; Andersson, Agneta; Andreé, Lotta; Birzniece, Vita; Bixo, Marie; Björn, Inger; Haage, David; Isaksson, Monica; Johansson, Inga-Maj; Lindblad, Charlott; Lundgren, Per; Nyberg, Sigrid; Odmark, Inga-Stina; Strömberg, Jessica; Sundström-Poromaa, Inger; Turkmen, Sahruh; Wahlström, Göran; Wang, Mingde; Wihlbäck, Anna-Carin; Zhu, Di; Zingmark, Elisabeth (December 2003). "Pathogenesis in Menstrual Cycle-Linked CNS Disorders". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1007 (1): 42–53. Bibcode:2003NYASA1007...42B. doi:10.1196/annals.1286.005. PMID 14993039.

- Herzog, Andrew G.; Fowler, Kristen M.; Sperling, Michael R.; Massaro, Joseph M.; Progesterone Trial Study, Group. (May 2015). "Distribution of seizures across the menstrual cycle in women with epilepsy". Epilepsia. 56 (5): e58–e62. doi:10.1111/epi.12969. PMID 25823700.

- Herzog, Andrew G.; Klein, Pavel; Rand, Bernard J. (October 1997). "Three Patterns of Catamenial Epilepsy". Epilepsia. 38 (10): 1082–1088. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01197.x. PMID 9579954.

- Logothetis, J.; Harner, R.; Morrell, F.; Torres, F. (1 May 1959). "The role of estrogens in catamenial exacerbation of epilepsy". Neurology. 9 (5): 352–60. doi:10.1212/wnl.9.5.352. PMID 13657294.

- Herzog, Andrew G. (May 2015). "Catamenial epilepsy: Update on prevalence, pathophysiology and treatment from the findings of the NIH Progesterone Treatment Trial". Seizure. 28: 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2015.02.024. PMID 25770028.

- Navis, Allison; Harden, Cynthia (17 May 2016). "A Treatment Approach to Catamenial Epilepsy". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 18 (7): 30. doi:10.1007/s11940-016-0413-6. PMID 27188699. S2CID 22399239.

- Brockington 2017, pp. 293–295.

- Raju, MSVK (July 1997). "Menstruation-related periodic hypersomnia: successful outcome with carbamazepine (A Case Report)". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 53 (3): 226–227. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(17)30723-2. PMC 5530980. PMID 28769491.

References

- Brockington, Ian (2017). The Psychoses of Menstruation and Childbearing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-72076-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)