Megaron

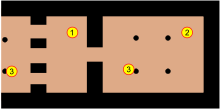

The megaron (/ˈmɛɡəˌrɒn/; Ancient Greek: μέγαρον, [mégaron]), plural megara /ˈmɛɡərə/, was the great hall in ancient Greek palace complexes.[1] Architecturally, it was a rectangular hall that was surrounded by four columns, fronted by an open, two-columned portico, and had a central, open hearth that vented though an oculus in the roof.[2] The megaron also contained the throne-room of the wanax, or Mycenaean ruler, whose throne was located in the main room with the central hearth.[3] Similar architecture is found in the Ancient Near East though the presence of the open portico, generally supported by columns, is particular to the Aegean.[4] Megara are sometimes referred to as "long-rooms", as defined by their rectangular (non-square) shape and the position of their entrances, which are always along the shorter wall so that the depth of the space is larger than the width.[5] There were often many rooms around the central megaron, such as archive rooms, offices, oil-press rooms, workshops, potteries, shrines, corridors, armories, and storerooms for such goods as wine, oil and wheat.[6]

Structure

Rectilinear halls were a characteristic theme of ancient Greek architecture.[7] The Mycenaean megaron originated and evolved from the megaroid, or large hall-centered rectangular building, of mainland Greece dating back to the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.[1][7] Furthermore, it served as the architectural precursor to the Greek temples of the Archaic and Classical periods.[8] With respect to its structural layout, the megaron includes a columned entrance, a pronaos and a central naos (cella) with early versions of it having one of many roof types (i.e., pitched, flat, barrel).[5] The roof, specifically, was supported by wooden beams[9] and since the aforesaid roof types are always destroyed in the remnants of the early megaron, the definite roof type is unknown.[5] The floor was made of patterned concrete and covered in carpet.[10] The walls, constructed out of mud brick,[11] were decorated with fresco paintings.[8] There were wood-ornamented metal doors, often two-leaved,[12] and footbaths were also used in the megaron as attested in Homer's Odyssey where Odysseus's feet were washed by Eurycleia.[13] The proportions involving a larger length than width are similar structurally to early Doric temples.[14]

Purpose

The megaron was used for sacrificial processions,[15] as well as for royal functions and court meetings.[4]

Examples

A famous megaron is in the large reception hall of the king in the palace of Tiryns, the main room of which had a raised throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four Minoan-style wooden columns that served as supports for the roof.[5] The Cretan elements in the Tiryns megaron were adopted by the Mycenaeans from the palace type found in Minoan architecture.[5] Frescoes from Pylos show figures eating and drinking, which were important activities in Greek culture.[15] Artistic portrayals of bulls, a common zoomorphic motif in Mycenaean vase painting,[16] appear on Greek megaron frescoes such as the one in the Pylos megaron where a bull is depicted at the center of a Mycenaean procession.[15] Other famous megara include the ones at the Mycenaean palaces of Thebes and Mycenae.[17] Different Greek cultures had their own unique megara; for example, the people of the Greek mainland tended to separate their central megaron from the other rooms whereas the Cretans did not do this.[18]

References

Citations

- Biers 1996, p. 69: "Perhaps the most conspicuous and distinctive feature of Mycenaean architecture is the central hall, or megaron, which is found not only in the palaces but in private houses as well. A typical mainland form, traceable at least to Early Helladic and perhaps to Neolithic predecessors [...]"

- Pullen 2008, p. 37.

- Kleiner 2016, "Chapter 4 The Prehistoric Aegean", p. 94; Neer 2012.

- "Megaron". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Müller 1944, pp. 342−348.

- Pentreath 2006, "Pre-Classical Beginnings".

- Hitchcock 2010, pp. 200–209.

- Cartwright 2019.

- Werner 1993, p. 16; Rider 1916, pp. 179–180.

- Diehl 1893, p. 53.

- Werner 1993, p. 23.

- Rider 1916, p. 180.

- Rider 1916, p. 183; Homer. Odyssey, XIX.316.

- Rider 1916, p. 140.

- Wright 2004, pp. 161–162.

- Wright 2004, p. 160 (Footnote #116).

- Werner 1993.

- Rider 1916, p. 127.

Sources

- Biers, William R. (1996). The Archaeology of Greece: An Introduction. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-43173-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cartwright, Mark (2019). "Mycenaean Civilization". Ancient History Encyclopedia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diehl, Charles (1893). Excursions in Greece to Recently Explored Sites of Classical Interest: Mycenae, Tiryns, Dodona, Delos, Athens, Olympia, Eleusis, Epidaurus, Tanagra. London: H. Grevel and Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hitchcock, Louise A. (2010). "Chapter 15. Mycenaean Architecture". In Cline, Eric H. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 200−209. ISBN 978-0-19-536550-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleiner, Fred S., ed. (2016). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History. I (15th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-30-554486-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Müller, Valentine (1944). "Development of the "Megaron" in Prehistoric Greece". Archaeological Institute of America. 48 (4): 342–348. JSTOR 499900.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neer, Richard T. (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500–c. 150 BCE. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28877-1. OCLC 745332893.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pentreath, Guy (2006). "ABCs of Greek Architecture". The New York Times: Travel. Fodors LLC. Retrieved 18 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pullen, Daniel (2008). "The Early Bronze Age in Greece". In Shelmerdine, Cynthia W. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–46. ISBN 978-0-521-81444-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rider, Bertha Carr (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to Hellenistic Age. London: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Werner, Kjell (1993). The Megaron during the Aegean and Anatolian Bronze Age: A Study of Occurrence, Shape, Architectural Adaptation, and Function. Jonsered: Paul Åströms Förlag. ISBN 978-9-17-081092-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, James C. (2004). "A Survey of Evidence for Feasting in Mycenaean Society". Hesperia. 73 (2): 133–178. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.675.9036. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.133. ProQuest 216525567.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Homer's Odyssey contains detailed references to the megaron of Odysseus.

- Hopkins, Clark (1968). "The Megaron of the Mycenaean Palace" (PDF). Studi Micenea ed Egeo-Anatolici. 6: 45−53.

- Konsolaki-Yannopoulou, Eleni (2004). "Mycenaean Religious Architecture: The Archaeological Evidence from Ayios Konstantinos, Methana". In Wedde, Michael (ed.). Celebrations: Sanctuaries and the Vestiges of Cult Activity (PDF). Papers from the Norwegian Institute at Athens 6. Athens. pp. 61–94.

- Vermeule, Emily (1972). Greece in the Bronze Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

External links

- Lee, Stephanie (2007). "Megaron". JIAAW Workplace: Archaeologies of the Greek Past. Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World (Brown University).