Marn Grook

Marn Grook or marngrook, from the Woiwurung language for "ball" or "game", is a collective name given the traditional Indigenous Australian football game played at gatherings and celebrations of sometimes more than 100 players.

Marn Grook featured punt kicking and catching a stuffed ball. It involved large numbers of players, and games were played over an extremely large area. The game was subject to strict behavioural protocols and for instance all players had to be matched for size, gender and skin group relationship. However, to observers the game appeared to lack a team objective, having no real rules, or scoring. A winner could only be declared if one of the sides agreed that the other side had played better. Individual players who consistently exhibited outstanding skills, such as leaping high over others to catch the ball, were often praised, but proficiency in the sport gave them no tribal influence.[1]

Anecdotal evidence supports such games being played all over south-eastern Australia, including the Djabwurrung and Jardwadjali[2] people and other tribes in the Wimmera, Mallee and Millewa regions of western Victoria (However, according to some accounts, the range extended to the Wurundjeri in the Yarra Valley, the Gunai people of Gippsland, and the Riverina in south-western New South Wales. The Warlpiri tribe of Central Australia played a very similar kicking and catching game with a possum skin ball, and the game was known as pultja.[3]

The earliest accounts emerged decades after the European settlement of Australia, mostly from the colonial Victorian explorers and settlers. The earliest anecdotal account was in 1841, a decade prior to the Victorian gold rush. Although the consensus among historians is that Marn Grook existed before European arrival, it is not clear how long the game had been played in Victoria or elsewhere on the Australian continent.[4][5][6]

Some historians claim that Marn Grook had a role in the formation of Australian rules football, which originated in Melbourne in 1858 and was codified the following year by members of the Melbourne Football Club.[7] This connection has become culturally important to many Indigenous Australians, including celebrities and professional footballers[8] from communities in which Australian rules football is highly popular.[9]

Eyewitness accounts

Robert Brough Smyth, in an 1878 book, The Aborigines of Victoria, quoted William Thomas, a Protector of Aborigines in Victoria, who stated that in about 1841 he had witnessed Wurundjeri Aborigines east of Melbourne playing the game.

- The men and boys joyfully assemble when this game is to be played. One makes a ball of possum skin, somewhat elastic, but firm and strong. ...The players of this game do not throw the ball as a white man might do, but drop it and at the same time kicks it with his foot, using the instep for that purpose. ...The tallest men have the best chances in this game. ...Some of them will leap as high as five feet from the ground to catch the ball. The person who secures the ball kicks it. ...This continues for hours and the natives never seem to tire of the exercise.[10]

The game was a favourite of the Wurundjeri-willam clan and the two teams were sometimes based on the traditional totemic moieties of Bunjil (eagle) and Waang (crow). Robert Brough-Smyth saw the game played at Coranderrk Mission Station, where ngurungaeta (elder) William Barak discouraged the playing of imported games like cricket and encouraged the traditional native game of marn grook.[11]

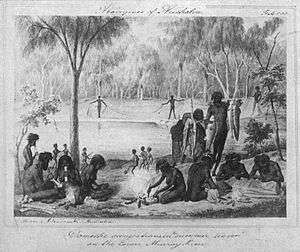

An 1857 sketch found in 2007 describes an observation by Victorian scientist William Blandowski, of the Latjilatji people playing a football game near Merbein, on his expedition to the junction of the Murray and Darling Rivers.[12] The Australian Sports Commission considers this sketch to be depicting the game of Woggabaliri. The image is inscribed:[12]

- "A group of children is playing with a ball. The ball is made out of typha roots (roots of the bulrush). It is not thrown or hit with a bat, but is kicked up in the air with a foot. The aim of the game – never let the ball touch the ground."

Historian Greg de Moore comments:[12]

- "What I can say for certain is that it's the first image of any kind of football that's been discovered in Australia. It pre-dates the first European images of any kind of football, by almost ten years in Australia. Whether or not there is a link between the two games in some way for me is immaterial because it really highlights that games such as Marn Grook, which is one of the names for Aboriginal football, were played by Aborigines and should be celebrated in their own right."

In 1889, anthropologist Alfred Howitt, wrote that the game was played between large groups on a totemic basis – the white cockatoos versus the black cockatoos, for example, which accorded with their skin system. Acclaim and recognition went to the players who could leap or kick the highest. Howitt wrote:

This game of ball-playing was also practised among the Kurnai, the Wolgal (Tumut river people), the Wotjoballuk as well as by the Woiworung, and was probably known to most tribes of south-eastern Australia. The Kurnai made the ball from the scrotum of an "old man kangaroo", the Woiworung made it of tightly rolled up pieces of possum skin. It was called by them "mangurt". In this tribe the two exogamous divisions, Bunjil and Waa, played on opposite sides. The Wotjoballuk also played this game, with Krokitch on one side and Gamutch on the other. The mangurt was sent as a token of friendship from one to another.[13]

Relationship with Australian rules football

.jpg)

Since the 1980s, some commentators, including Martin Flanagan,[4] Jim Poulter and Col Hutchinson postulated that Australian rules football pioneer Tom Wills could have been inspired by Marn Grook.[5]

The theory hinges on evidence which is circumstantial and anecdotal. Tom Wills was raised in Victoria's Western District. As the only white child in the district, it is said that he was fluent in the languages of the Djab wurrung and frequently played with local Aboriginal children on his father's property, Lexington, outside modern-day Moyston.[14] This story has been passed down through the generations of his family.[15]

Col Hutchison, former historian for the AFL, wrote in support of the theory postulated by Flanagan, and his account appears on an official AFL memorial to Tom Wills in Moyston, erected in 1998.

While playing as a child with Aboriginal children in this area [Moyston] he [Tom Wills] developed a game which he later utilised in the formation of Australian Football.

— As written by Col Hutchison on the plaque at Moyston donated by the Australian Football League in 1998.

Sports historian Gillian Hibbins—who researched the origins of Australian rules football for the Australian Football League's official account of the game's history as part of its 150th anniversary celebrations—sternly rejects the theory, stating that while Marn Grook was "definitely" played around Port Fairy and throughout the Melbourne area, there is no evidence that the game was played north of the Grampians or by the Djabwurrung people, and the claim that Wills observed and possibly played the game is improbable:[16]

Hibbin's account was widely publicised[16] causing significant controversy and offending prominent Indigenous footballers who openly criticised the publication.[17]

James Dawson, in his 1881 book titled Australian Aborigines, described a game, which he referred to as 'football', where the players of two teams kick around a ball made of possum fur.[18][19]

Each side endeavours to keep possession of the ball, which is tossed a short distance by hand, then kicked in any direction. The side which kicks it oftenest and furthest gains the game. The person who sends it the highest is considered the best player, and has the honour of burying it in the ground till required the next day. The sport is concluded with a shout of applause, and the best player is complimented on his skill. The game, which is somewhat similar to the white man's game of football, is very rough...

— James Dawson in his 1881 book Australian Aborigines.

In the appendix of Dawson's book, he lists the word Min'gorm for the game in the Aboriginal language Chaap Wuurong.[20][21]

Professor Jenny Hocking of Monash University and Nell Reidy have also published eyewitness accounts of the game having been played in the area in which Tom Wills grew up.[22]

In his exhaustive research of the first four decades of Australian rules football, historian Mark Pennings "could not find evidence that those who wrote the first rules were influenced by the Indigenous game of Marngrook".[23] Melbourne Cricket Club researcher Trevor Ruddell wrote in 2013 that Marn Grook "has no causal link with, nor any documented influence upon, the early development of Australian football."[24]

Chris Hallinan and Barry Judd describe the historical perspective of the history of Australian Rules as Anglo-centric, having been reluctant to acknowledge the Indigenous contribution. They go on to suggest this is an example of white Australians struggling to accept Indigenous peoples "as active and intelligent human subjects".[25]

If Tom Wills had have said "Hey, we should have a game of our own more like the football the black fellas play" it would have killed it stone dead before it was even born.

— Statement by Jim Poulter During 7.30 Report (22 May 2008).[26]

Comparisons with Australian rules football

Advocates of these theories have drawn comparisons in the catching of the kicked ball (the mark) and the high jumping to catch the ball (the spectacular mark) that have been attributes of both games.[6] However, the connection is speculative. For instance spectacular high marking did not become common in Australian rules football until the 1880s.

Marn Grook and the Australian rules football term "mark"

Some claim that the origin of the Australian rules term mark, meaning a clean, fair catch of a kicked ball, followed by a free kick, is derived from the Aboriginal word mumarki used in Marn Grook, and meaning "to catch".[27][28] The application of the word "mark" in "foot-ball" (and in many other games) dates to the Elizabethan era and is likely derived from the practice where a player marks the ground to show where a catch had been taken or where the ball should be placed.[29] The use of the word "mark" to indicate an "impression or trace forming a sign" on the ground dates to c1200.[30]

In popular culture

Due to the theories of shared origins, marn grook features heavily in Australian rules football and Indigenous culture.

A documentary titled Marn Grook was first released in 1996.[31]

In 2002, in a game at Stadium Australia, the Sydney Swans and Essendon Football Club began to compete for the Marngrook Trophy, awarded after home-and-away matches each year between the two teams in the Australian Football League. Though it commemorates marn grook, the match is played under normal rules of the AFL rather than those of the traditional Aboriginal game.[32]

Marn Grook is the subject of children's books, including Neridah McMullin's Kick it to Me! (2012), an account of Tom Wills' upbringing, and Marngrook: The Long Ago Story of Aussie Rules (2012) by Indigenous writer Titta Secombe.

The Marngrook Footy Show, an Indigenous variation of the AFL Footy Show, began in Melbourne in 2007 and has since been broadcast on National Indigenous Television, ABC 2, and Channel 31.

See also

References

- The Sports Factor, ABC Radio National, program first broadcast on 5 September 2008.

- Aboriginal Heritage - History and Heritage - Grampians, Victoria, Australia, archived from the original on 22 April 2011, retrieved 5 January 2011

- "Aboriginal Rules". 2007 video documentary by the Walpiri Media Association

- Martin Flanagan, The Call. St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin, 1998, p. 8 Martin Flanagan, 'Sport and Culture'

- Gregory M de Moore. Victoria University. from Football Fever. Crossing Boundaries. Maribyrnong Press, 2005

- David Thompson, "Aborigines were playing possum", Herald Sun, 27 September 2007. Accessed 3 November 2008

- "A code of our own" celebrating 150 years of the rules of Australian football The Yorker: Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 39, Autumn 2009

- Morrissey, Tim (15 May 2008). "Goodes racist, says AFL historian". Herald Sun.

- AFL turning Indigenous dreamtime to big time - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- Robert Brough-Smyth The Aborigines of Victoria 1878 Pg.176

- Isabel Ellender and Peter Christiansen, pp45 People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days, Merri Creek Management Committee, 2001 ISBN 0-9577728-0-7

- Farnsworth, Sarah (21 September 2007). "Kids play kick to kick -1850s style". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- AW Howitt, "Notes on Australian Message Sticks and Messengers", Journal of the Anthropological Institute, London, 1889, p 2, note 4, Reprinted by Ngarak Press, 1998, ISBN 1-875254-25-0

- Minister opens show exhibition celebrating Aussie Rules' Koorie Heritage Archived 8 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Government Media Release accessed 4 June 2007

- AFL News | Real Footy

- AFL's native roots a 'seductive myth' The Australian 22 March 2008

- Goodes racist, says AFL historian

- James Dawson (1881). Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria, Australia. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-85575-118-0.

- Dawson, James (1881). "Australian Aborigines". archive.org. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- James Dawson (1881). Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria, Australia. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-85575-118-0.

- Dawson, James (1980). "Australian Aborigines". archive.org. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Hocking, Jenny; Nell, Reidy (2016). "Marngrook, Tom Wills and the Continuing Denial of Indigenous History: On the origins of Australian football". Meanjin. Meanjin Company Ltd. 75 (2): 83–93.

- Cardosi, Adam (18 October 2013). "Origins of Australian Football", Australian Football. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- Ruddell, Trevor (19 December 2013). "Pompey Austin - Aboriginal football pioneer", Australian Football. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- Hallinan, Chris & Judd, Barry (2012). "Duelling paradigms: Australian Aborigines, marn-grook and football histories". Sport in Society. 15 (7): 975–986. doi:10.1080/17430437.2012.723364.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Debate over AFL origins continues: The AFL is celebrating its 150th season and this weekend the event will be marked by an Indigenous round with a special match between Essendon and Richmond called "Dreamtime at the G". But the celebrations have reignited a long running debate over the sport's origins. [online]. 7.30 Report (ABC1); Time: 19:42; Broadcast Date: Thursday, 22 May 2008; Duration: 5 min., 18 sec.

- Early History

- Aboriginal Football – Marn Grook Archived 12 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Joseph Strutt The sports and pastimes of the people of England from the earliest period. Harvard University 1801

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- Marn Grook (1996) (VHS. Classification: G. Runtime: 45 min. Produced In: Australia. Produced by: CAAMA (Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association), based in Alice Springs (NT). Directed By: Steve McGregor. Language: English.)

- Richard Hinds, Marn Grook, a native game on Sydney's biggest stage, The Age, 2 March 1991. Accessed 9 November 2008

External links

- "Genesis of footy and its Indigenous heart", ABC radio — Interviews with Titta Secombe, author of Marngrook, the long ago story of Aussie Rules, and Greg de Moore, biographer of Tom Wills

.svg.png)