Maravar

Maravar (also known as Maravan and Marava) is a branch of Mukkulathor/ Thevar Community Tamil community in the state of Tamil Nadu. These people are one of the three branches of the Mukkulathor

.[1] Members of the Maravar community often use the honorific title Thevar.[2][3][4]

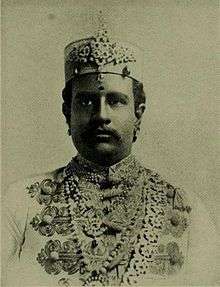

Bhaskara Sethupathi, former Marava ruler of Ramnad kingdom | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India: Ramnad, Madurai, Tirunelveli regions of Tamil Nadu | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kallar, Agamudayar, Tamil people |

The Sethupathi rulers of the erstwhile Ramnad kingdom hailed from this community.[5] As early as the medieval period, the Maravar community had a reputation for thievery, banditry and robbery.[6][7][8]

Etymology

The term Maravar has diverse proposed etymologies;[9] it may come simply from a Tamil word maravar (sin) murder [10] [11] or a term meaning "bravery".[12]

Divisions

There are 7 sub divisions in the Maravar Class. They are Semba Nadu, Kondayan Kottai, Appanur Nadu, Agattha, Oru NAdu, Uppu Katti and Kuruchi Kattu. Among these sub divisions Semba Nadu Maravar are the Principle ones.

History

The Maravars have a long military tradition. They were the inhabitants of the Drylands of ancient Tamilakam, known as Paalai in Sangam literature.

Social Status

According to Pamela G Price the Maravar were warriors who were Rajas of some Zamindaris. During the British colonial era, the Maravars were sometimes recorded as Kshatriyas by the legal officers involved in Zamindari litigation proceedings but more often they classified as Shudras. Occasionally the Setupathis had to respond to the charge they were not ritually pure.[13]

According to historian S. N Sadasivan,

No Marava prince however, resorted to detaching himself from his people by undergoing the costly process of attaining Kshatriyahood but the Brahmins always thronged to his mansion to perform religious ceremonies befitting to the Kshatriya and to receive rewards.. ..Conversion to Kshatriyahood was an ingenious means by which the Brahmins isolated the elite from the masses to keep control of the political power. They were cautious that a few alone in the tribe were accorded the status of Kshatriyas, and the others were branded as Sudras and pushed to the bottom as otherwise, the structural strength of the social pyramid would be adversely affected.[14]

During the formation of Tamilaham the maravar were brought in as socially outcast tribes or traditionally as lowest entrants into the shudra category. The Maravas to this day are feared as a thieving tribe and are an ostracised group in Tirunelveli region. [15][16]

See also

References

- Dirks, Nicholas B. (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-47208-187-5.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-52154-885-4.

- Hardgrave, Robert L. (1969). The Nadars of Tamilnad: The Political Culture of a Community in Change. University of California Press. p. 280.

- Pandian, Anand (2009). Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India. Duke University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-82239-101-2.

- Pamela G. Price. Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press, 14-Mar-1996 - History - 220 pages. p. 26.

- Dirks, Nicholas (2007). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 74.

- Balasubramanian, R (2001). Social and Economic Dimensions of Caste Organisations in South Indian States. University of Madras. p. 88.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Women and Work in Precolonial India: A Reader. Sage Publications. p. 74.

- VenkatasubramanianIndia, T. K. (1986). Political Change and Agrarian Tradition in South India, C. 1600-1801: A Case Study. Mittal Publications. p. 49.

- Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Taylor and Francis. p. 213.

- Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1903). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Published for the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland by Trübner & Co. p. 57.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8108-5379-9.

- Price, Pamela (1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. University of Cambridge. p. 62.

- S. N. Sadasivan. A Social History of India. APH Publishing, 2000. p. 249.

- Ramasamy, Vijaya (2016). Women and work in Precolonial India. SAGE. p. 62.

- Parkin, Robert (2001). Perilous Transactions. Sikshasandhan. p. 130.