Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu is a 15th-century Inca citadel, located in the Eastern Cordillera of southern Peru, on a 2,430-metre (7,970 ft) mountain ridge.[2][3] It is located in the Cusco Region, Urubamba Province, Machupicchu District,[4] above the Sacred Valley, which is 80 kilometres (50 mi) northwest of Cuzco. The Urubamba River flows past it, cutting through the Cordillera and creating a canyon with a tropical mountain climate.[5]

Machu Picchu in 2009 | |

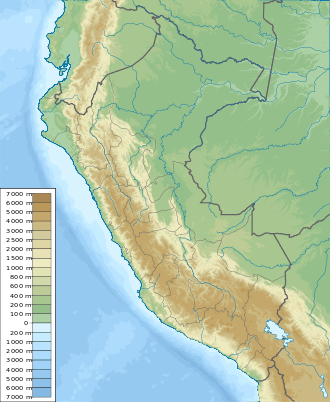

Shown within Peru | |

| Location |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 13°09′48″S 72°32′44″W |

| Height | 2,430 metres (7,970 ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 1450 |

| Abandoned | 1572[1] |

| Cultures | Inca civilization |

| Site notes | |

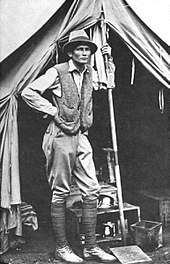

| Archaeologists | Hiram Bingham |

| Official name | Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | i, iii, vii, ix |

| Designated | 1983 (7th session) |

| Reference no. | 274 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

For most speakers of English or Spanish, the first 'c' in Picchu is silent. In English, the name is pronounced /ˌmɑːtʃuː piːtʃuː/[6][7] or /ˌmɑːtʃuː piːktʃuː/,[7][8] in Spanish as [ˈmatʃu ˈpitʃu] or [ˈmatʃu ˈpiktʃu],[9] and in Quechua (Machu Pikchu)[10] as [ˈmatʃʊ ˈpɪktʃʊ].

Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was constructed as an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti (1438–1472). Often mistakenly referred to as the "Lost City of the Incas", it is the most familiar icon of Inca civilization. The Incas built the estate around 1450 but abandoned it a century later at the time of the Spanish conquest. Although known locally, it was not known to the Spanish during the colonial period and remained unknown to the outside world until American historian Hiram Bingham brought it to international attention in 1911.

Machu Picchu was built in the classical Inca style, with polished dry-stone walls. Its three primary structures are the Intihuatana, the Temple of the Sun, and the Room of the Three Windows. Most of the outlying buildings have been reconstructed in order to give tourists a better idea of how they originally appeared. By 1976, 30% of Machu Picchu had been restored and restoration continues.[12]

Machu Picchu was declared a Peruvian Historic Sanctuary in 1981 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983.[3] In 2007, Machu Picchu was voted one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in a worldwide Internet poll.[13]

Etymology

In the Quechua language, machu means "old" or "old person", while pikchu means either "portion of coca being chewed" or "pyramid, pointed multi-sided solid; cone".[14] Thus the name of the site is sometimes interpreted as "old mountain".[15]

History

Machu Picchu is believed (by Richard L. Burger) to be built starting 1450–1460.[17] Construction appears to date from two great Inca rulers, Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui (1438–1471) and Túpac Inca Yupanqui (1472–1493).[18][19]:xxxvi There is a consensus among archaeologists that Pachacutec ordered the construction of the royal estate for himself, most likely after a successful military campaign. Though Machu Picchu is considered to be a "royal" estate, surprisingly, it would not have been passed down in the line of succession. Rather it was used for 80 years before being abandoned, seemingly because of the Spanish Conquests in other parts of the Inca Empire.[17] It is possible that most of its inhabitants died from smallpox introduced by travelers before the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the area.[20]

Daily life in Machu Picchu

During its use as a royal estate, it is estimated that about 750 people lived there, with most serving as support staff (yanaconas, yana)[17][21] who lived there permanently. Though the estate belonged to Pachacutec, religious specialists and temporary specialized workers (mayocs) lived there as well, most likely for the ruler's well-being and enjoyment. During the harsher season, staff dropped down to around a hundred servants and a few religious specialists focused on maintenance alone.[17]

Studies show that according to their skeletal remains, most people who lived there were immigrants from diverse backgrounds. They lacked the chemical markers and osteological markers they would have if they had been living there their whole lives. Instead, there was bone damage from various species of water parasites indigenous to different areas of Peru. There were also varying osteological stressors and varying chemical densities suggesting varying long-term diets characteristic of specific regions that were spaced apart.[22] These diets are composed of varying levels of maize, potatoes, grains, legumes, and fish, but the overall most recent short-term diet for these people was composed of less fish and more corn. This suggests that several of the immigrants were from more coastal areas and moved to Machu Picchu where corn was a larger portion of food intake.[21] Most skeletal remains found at the site had lower levels of arthritis and bone fractures than those found in most sites of the Inca Empire. Inca individuals who had arthritis and bone fractures were typically those who performed heavy physical labor (such as the Mit'a) or served in the Inca military.[17]

Animals are also suspected to have immigrated to Machu Picchu as there were several bones found that were not native to the area. Most animal bones found were from llamas and alpacas. These animals naturally live at altitudes of 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) rather than the 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) elevation of Machu Picchu. Most likely, these animals were brought in from the Puna region[23] for meat consumption and for their pelts. Guinea pigs were also found at the site in special burial caves, suggesting that they were at least used for funerary rituals,[17] as it was common throughout the Inca Empire to use them for sacrifices and meat.[24] Six dogs were also recovered from the site. Due to their placements among the human remains, it is believed that they served as companions of the dead.[17]

Agriculture

.jpg)

Much of the farming done at Machu Picchu was done on its hundreds of man-made terraces. These terraces were a work of considerable engineering, built to ensure good drainage and soil fertility while also protecting the mountain itself from erosion and landslides. However, the terraces were not perfect, as studies of the land show that there were landslides that happened during the construction of Machu Picchu. Still visible are places where the terraces were shifted by landslides and then stabilized by the Inca as they continued to build around the area.[25]

It is estimated that the area around the site has received more than 1,800 mm (71 in) of rain per year since AD 1450, which was more than needed to support crop growth there. Because of the large amount of rainfall at Machu Picchu, it was found that irrigation was not needed for the terraces. The terraces received so much rain that they were built by Incan engineers specifically to allow for ample drainage of the extra water. Excavation and soil analyses done by Kenneth Wright [26][27][28] in the 90s showed that the terraces were built in layers, with a bottom layer of larger stones covered by loose gravel.[25] On top of the gravel was a layer of mixed sand and gravel packed together, with rich topsoil covering all of that. It was shown that the topsoil was probably moved from the valley floor to the terraces because it was much better than the soil higher up the mountain.[17]

However, it has been found that the terrace farming area makes up only about 4.9 ha (12 acres) of land, and a study of the soil around the terraces showed that what was grown there was mostly corn and potatoes, which was not enough to support the 750+ people living at Machu Picchu. This explains why when studies were done on the food that the Inca ate at Machu Picchu, it was found that most of what they ate was imported from the surrounding valleys and farther afield.[22]

Encounters

Even though Machu Picchu was located only about 80 kilometers (50 mi) from the Inca capital in Cusco, the Spanish never found it and so did not plunder or destroy it, as they did many other sites.[29][19]:xxx The conquistadors had notes of a place called Piccho, although no record of a Spanish visit exists. Unlike other locations, sacred rocks often defaced by the conquistadors remain untouched at Machu Picchu.[30]

Over the centuries, the surrounding jungle overgrew the site, and few outside the immediate area knew of its existence. The site may have been discovered and plundered in 1867 by a German businessman, Augusto Berns.[31] Some evidence indicates that the German engineer J. M. von Hassel arrived earlier. Maps show references to Machu Picchu as early as 1874.[32]

In 1911 American historian and explorer Hiram Bingham traveled the region looking for the old Inca capital and was led to Machu Picchu by a villager, Melchor Arteaga. Bingham found the name Agustín Lizárraga and the date 1902 written in charcoal on one of the walls. Though Bingham was not the first to visit the ruins, he was considered the scientific discoverer who brought Machu Picchu to international attention. Bingham organized another expedition in 1912 to undertake major clearing and excavation.[19]:xxx–xxxi

In 1981, Peru declared an area of 325.92 square kilometres (125.84 sq mi) surrounding Machu Picchu a "historic sanctuary". In addition to the ruins, the sanctuary includes a large portion of the adjoining region, rich with the flora and fauna of the Peruvian Yungas and Central Andean wet puna ecoregions.[33]

In 1983, UNESCO designated Machu Picchu a World Heritage site, describing it as "an absolute masterpiece of architecture and a unique testimony to the Inca civilization".[2]

First American expedition

Bingham was a lecturer at Yale University, although not a trained archaeologist. In 1909, returning from the Pan-American Scientific Congress in Santiago, he travelled through Peru and was invited to explore the Inca ruins at Choqquequirau in the Apurímac Valley. He organized the 1911 Yale Peruvian Expedition in part to search for the Inca capital, which was thought to be the city of Vitcos. He consulted Carlos Romero, one of the chief historians in Lima who showed him helpful references and Father Antonio de la Calancha’s Chronicle of the Augustinians. In particular, Ramos thought Vitcos was "near a great white rock over a spring of fresh water." Back in Cusco again, Bingham asked planters about the places mentioned by Calancha, particularly along the Urubamba River. According to Bingham, "one old prospector said there were interesting ruins at Machu Picchu," though his statements "were given no importance by the leading citizens." Only later did Bingham learn that Charles Wiener also heard of the ruins at Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu, but was unable to reach them.[19]

Armed with this information the expedition went down the Urubamba River. En route, Bingham asked local people to show them Inca ruins, especially any place described as having a white rock over a spring.[19]:137

At Mandor Pampa, Bingham asked farmer and innkeeper Melchor Arteaga if he knew of any nearby ruins. Arteaga said he knew of excellent ruins on the top of Huayna Picchu.[34] The next day, 24 July, Arteaga led Bingham and Sergeant Carrasco across the river on a log bridge and up the Huayna Picchu mountain. At the top of the mountain, they came across a small hut occupied by a couple of Quechua, Richard and Alvarez, who were farming some of the original Machu Picchu agricultural terraces that they had cleared four years earlier. Alvarez's 11-year-old son, Pablito, led Bingham along the ridge to the main ruins.[30]

The ruins were mostly covered with vegetation except for the cleared agricultural terraces and clearings used by the farmers as vegetable gardens. Because of the vegetation, Bingham was not able to observe the full extent of the site. He took preliminary notes, measurements, and photographs, noting the fine quality of Inca stonework of several principal buildings. Bingham was unclear about the original purpose of the ruins, but decided that there was no indication that it matched the description of Vitcos.[19]:141, 186–187

The expedition continued down the Urubamba and up the Vilcabamba Rivers examining all the ruins they could find. Guided by locals, Bingham rediscovered and correctly identified the site of the old Inca capital, Vitcos (then called Rosaspata), and the nearby temple of Chuquipalta. He then crossed a pass and into the Pampaconas Valley where he found more ruins heavily buried in the jungle undergrowth at Espíritu Pampa, which he named "Trombone Pampa".[35] As was the case with Machu Picchu, the site was so heavily overgrown that Bingham could only note a few of the buildings. In 1964, Gene Savoy further explored the ruins at Espiritu Pampa and revealed the full extent of the site, identifying it as Vilcabamba Viejo, where the Incas fled after the Spanish drove them from Vitcos.[36][19]:xxxv

Bingham returned to Machu Picchu in 1912 under the sponsorship of Yale University and National Geographic again and with the full support of Peruvian President Leguia. The expedition undertook a four-month clearing of the site with local labour, which was expedited with the support of the Prefect of Cuzco. Excavation started in 1912 with further excavation undertaken in 1914 and 1915. Bingham focused on Machu Picchu because of its fine Inca stonework and well-preserved nature, which had lain undisturbed since the site was abandoned. None of Bingham's several hypotheses explaining the site held up. During his studies, he carried various artifacts back to Yale. One prominent artifact was a set of 15th-century, ceremonial Incan knives made from bismuth bronze; they are the earliest known artifact containing this alloy.[37][38]

Although local institutions initially welcomed the exploration, they soon accused Bingham of legal and cultural malpractice.[39] Rumors arose that the team was stealing artifacts and smuggling them out of Peru through Bolivia. (In fact, Bingham removed many artifacts, but openly and legally; they were deposited in the Yale University Museum. Bingham was abiding by the 1852 Civil Code of Peru; the code stated that "archaeological finds generally belonged to the discoverer, except when they had been discovered on private land." (Batievsky 100)[40] ) Local press perpetuated the accusations, claiming that the excavation harmed the site and deprived local archaeologists of knowledge about their own history.[39] Landowners began to demand rent from the excavators.[39] By the time Bingham and his team left Machu Picchu, locals had formed coalitions to defend their ownership of Machu Picchu and its cultural remains, while Bingham claimed the artifacts ought to be studied by experts in American institutions.[39]

Human sacrifice and mysticism

Little information describes human sacrifices at Machu Picchu, though many sacrifices were never given a proper burial, and their skeletal remains succumbed to the elements.[41] However, there is evidence that retainers were sacrificed to accompany a deceased noble in the afterlife.[41]:107, 119 Animal, liquid and dirt sacrifices to the gods were more common, made at the Altar of the Condor. The tradition is upheld by members of the New Age Andean religion.[42]:263

Geography

Machu Picchu lies in the southern hemisphere, 13.164 degrees south of the equator.[43] It is 80 kilometres (50 miles) northwest of Cusco, on the crest of the mountain Machu Picchu, located about 2,430 metres (7,970 feet) above mean sea level, over 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) lower than Cusco, which has an elevation of 3,400 metres (11,200 ft).[43] As such, it had a milder climate than the Inca capital. It is one of the most important archaeological sites in South America, one of the most visited tourist attractions in Latin America[44] and the most visited in Peru.

Machu Picchu features wet humid summers and dry frosty winters, with the majority of the annual rain falling from October through to March.[43]

Machu Picchu is situated above a bow of the Urubamba River, which surrounds the site on three sides, where cliffs drop vertically for 450 metres (1,480 ft) to the river at their base. The area is subject to morning mists rising from the river.[29] The location of the city was a military secret, and its deep precipices and steep mountains provided natural defenses. The Inca Bridge, an Inca grass rope bridge, across the Urubamba River in the Pongo de Mainique, provided a secret entrance for the Inca army. Another Inca bridge was built to the west of Machu Picchu, the tree-trunk bridge, at a location where a gap occurs in the cliff that measures 6 metres (20 ft).

The city sits in a saddle between the two mountains Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu,[29] with a commanding view down two valleys and a nearly impassable mountain at its back. It has a water supply from springs that cannot be blocked easily. The hillsides leading to it were terraced, to provide more farmland to grow crops and to steepen the slopes that invaders would have to ascend. The terraces reduced soil erosion and protected against landslides.[45] Two high-altitude routes from Machu Picchu cross the mountains back to Cusco, one through the Sun Gate, and the other across the Inca bridge. Both could be blocked easily, should invaders approach along them.

Site

Layout

.jpg)

The site is roughly divided into an urban sector and an agricultural sector, and into an upper town and a lower town. The temples are in the upper town, the warehouses in the lower.[46]

The architecture is adapted to the mountains. Approximately 200 buildings are arranged on wide parallel terraces around an east–west central square. The various compounds, called kanchas, are long and narrow in order to exploit the terrain. Sophisticated channeling systems provided irrigation for the fields. Stone stairways set in the walls allowed access to the different levels across the site. The eastern section of the city was probably residential. The western, separated by the square, was for religious and ceremonial purposes. This section contains the Torreón, the massive tower which may have been used as an observatory.[47]

Located in the first zone are the primary archaeological treasures: the Intihuatana, the Temple of the Sun and the Room of the Three Windows. These were dedicated to Inti, their sun god and greatest deity.

The Popular District, or Residential District, is the place where the lower-class people lived. It includes storage buildings and simple houses.

The royalty area, a sector for the nobility, is a group of houses located in rows over a slope; the residence of the amautas (wise persons) was characterized by its reddish walls, and the zone of the ñustas (princesses) had trapezoid-shaped rooms. The Monumental Mausoleum is a carved statue with a vaulted interior and carved drawings. It was used for rites or sacrifices.

The Guardhouse is a three-sided building, with one of its long sides opening onto the Terrace of the Ceremonial Rock. The three-sided style of Inca architecture is known as the wayrona style.[48]

In 2005 and 2009, the University of Arkansas made detailed laser scans of the entire site and of the ruins at the top of the adjacent Huayna Picchu mountain. The scan data is available online for research purposes.[49]

Temple of the Sun or Torreon

This semicircular temple is built on the same rock overlying Bingham's "Royal Mausoleum", and is similar to the Temple of the Sun found in Cusco and the Temple of the Sun found in Pisac, in having what Bingham described as a "parabolic enclosure wall". The stonework is of ashlar quality. Within the temple is a 1.2 m by 2.7 m rock platform, smooth on top except for a small platform on its southwest quadrant. A "Serpent's Door" faces 340°, or just west of north, opening onto a series of 16 pools, and affording a view of Huayna Picchu. The temple also has two trapezoidal windows, one facing 65°, called the "Solstice Window", and the other facing 132°, called the "Qullqa Window". The northwest edge of the rock platform points out the Solstice Window to within 2’ of the 15th century June solstice rising Sun. For comparison, the angular diameter of the Sun is 32'. The Inca constellation Qullca, storehouse, can be viewed out the Qullqa Window at sunset during the 15th-century June Solstice, hence the window's name. At the same time, the Pleaides are at the opposite end of the sky. Also seen through this window on this night are the constellations Llamacnawin, Llama, Unallamacha, Machacuay, and the star Pachapacariq Chaska (Canopus).[50][51]

Intihuatana stone

The Intihuatana stone is one of many ritual stones in South America. These stones are arranged to point directly at the sun during the winter solstice.[53] The name of the stone (perhaps coined by Bingham) derives from Quechua language: inti means "sun", and wata-, "to tie, hitch (up)". The suffix -na derives nouns for tools or places. Hence Intihuatana is literally an instrument or place to "tie up the sun", often expressed in English as "The Hitching Post of the Sun". The Inca believed the stone held the sun in its place along its annual path in the sky. The stone is situated at 13°9'48" S. At midday on 11 November and 30 January, the sun stands almost exactly above the pillar, casting no shadow. On 21 June, the stone casts the longest shadow on its southern side, and on 21 December a much shorter shadow on its northern side.

Inti Mach'ay and the Royal Feast of the Sun

Inti Mach'ay is a special cave used to observe the Royal Feast of the Sun. This festival was celebrated during the Incan month of Qhapaq Raymi. It began earlier in the month and concluded on the December solstice. On this day, noble boys were initiated into manhood by an ear-piercing ritual as they stood inside the cave and watched the sunrise.[54]

Architecturally, Inti Mach'ay is the most significant structure at Machu Picchu. Its entrances, walls, steps, and windows are some of the finest masonry in the Incan Empire. The cave also includes a tunnel-like window unique among Incan structures, which was constructed to allow sunlight into the cave only during several days around the December solstice. For this reason, the cave was inaccessible for much of the year.[55] Inti Mach'ay is located on the eastern side of Machu Picchu, just north of the "Condor Stone." Many of the caves surrounding this area were prehistorically used as tombs, yet there is no evidence that Mach'ay was a burial ground.[56]

Construction

.jpg)

The central buildings use the classical Inca architectural style of polished dry-stone walls of regular shape. The Incas were masters of this technique, called ashlar, in which blocks of stone are cut to fit together tightly without mortar.

The site itself may have been intentionally built on fault lines to afford better drainage and a ready supply of fractured stone. "Machu Picchu clearly shows us that the Incan civilization was an empire of fractured rocks".[57]

The section of the mountain where Machu Picchu was built provided various challenges that the Incas solved with local materials. One issue was the seismic activity due to two fault lines. It made mortar and similar building methods nearly useless. Instead, the Inca mined stones from the quarry at the site,[58] lined them up and shaped them to fit together perfectly, stabilizing the structures. Inca walls have many stabilizing features: doors and windows are trapezoidal, narrowing from bottom to top; corners usually are rounded; inside corners often incline slightly into the rooms, and outside corners were often tied together by "L"-shaped blocks; walls are offset slightly from row to row rather than rising straight from bottom to top.

Heavy rainfall required terraces and stone chips to drain rain water and prevent mudslides, landslides, erosion, and flooding. Terraces were layered with stone chips, sand, dirt, and topsoil, to absorb water and prevent it from running down the mountain. Similar layering protected the large city center from flooding.[59] Multiple canals and reserves throughout the city provided water that could be supplied to the terraces for irrigation and to prevent erosion and flooding.

The Incas never used wheels in a practical way, although their use in toys shows that they knew the principle. The use of wheels in engineering may have been limited due to the lack of strong draft animals, combined with steep terrain and dense vegetation. The approach to moving and placing the enormous stones remains uncertain, probably involving hundreds of men to push the stones up inclines. A few stones have knobs that could have been used to lever them into position; the knobs were generally sanded away, with a few overlooked.

Roads and transportation

The Inca road system included a route to the Machu Picchu region. The people of Machu Picchu were connected to long-distance trade, as shown by non-local artifacts found at the site. For example, Bingham found unmodified obsidian nodules at the entrance gateway. In the 1970s, Burger and Asaro determined that these obsidian samples were from the Titicaca or Chivay obsidian source, and that the samples from Machu Picchu showed long-distance transport of this obsidian type in pre-Hispanic Peru.[60]

Thousands of tourists walk the Inca Trail to visit Machu Picchu each year.[61] They congregate at Cusco before starting on the one-, two-, four- or five-day journey on foot from kilometer 82 (or 77 or 85, four/five-day trip) or kilometer 104 (one/two-day trip) near the town of Ollantaytambo in the Urubamba valley, walking up through the Andes to the isolated city.

Tourism

| Machu Picchu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Machu Picchu is both a cultural and natural UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since its discovery in 1911, growing numbers of tourists have visited the site each year, including 1,411,279 in 2017.[63] As Peru's most visited tourist attraction and major revenue generator, it is continually exposed to economic and commercial forces. In the late 1990s, the Peruvian government granted concessions to allow the construction of a cable car and a luxury hotel, including a tourist complex with boutiques and restaurants and a bridge to the site.[64] Many people protested the plans, including Peruvians and foreign scientists, saying that more visitors would pose a physical burden on the ruins.[65] In 2018, plans were restarted to again construct a cable car to encourage Peruvians to visit Machu Picchu and boost domestic tourism.[66] A no-fly zone exists above the area.[67] UNESCO is considering putting Machu Picchu on its List of World Heritage in Danger.[64]

During the 1980s a large rock from Machu Picchu's central plaza was moved to a different location to create a helicopter landing zone. In the 1990s, the government prohibited helicopter landings. In 2006, a Cusco-based company, Helicusco, sought approval for tourist flights over Machu Picchu. The resulting license was soon rescinded.[68]

Tourist deaths have been linked to altitude sickness, floods and hiking accidents.[69][70][71][72] UNESCO received criticism for allowing tourists at the location given high risks of landslides, earthquakes and injury due to decaying structures.[73]

In 2014 nude tourism was a trend at Machu Picchu and Peru's Ministry of Culture denounced the activity. Cusco's Regional Director of Culture increased surveillance to end the practice.[74]

January 2010 evacuation

In January 2010, heavy rain caused flooding that buried or washed away roads and railways to Machu Picchu, trapping more than 2,000 locals and more than 2,000 tourists, later airlifted out to safety. Machu Picchu was temporarily closed,[75] reopening on 1 April 2010.[76]

Entrance restrictions

In July 2011, the Dirección Regional de Cultura Cusco (DRC) introduced new entrance rules to the citadel of Machu Picchu.[77] The tougher entrance rules attempted to reduce the effects of tourism. Entrance was limited to 2,500 visitors per day, and entrance to Huayna Picchu (within the citadel) was further restricted to 400 visitors per day. In 2018, additional restrictions were placed on entrance. Three entrance phases will be implemented, increased from two phases previously, to further help the flow of traffic and reduce degradation of the site due to tourism.[78]

In May 2012, a team of UNESCO conservation experts called upon Peruvian authorities to take "emergency measures" to further stabilize the site's buffer zone and protect it from damage, particularly in the nearby town of Aguas Calientes, which had grown rapidly.[79]

Cultural artifacts: Dispute between Peru and Yale University

In 1912, 1914 and 1915, Bingham removed thousands of artifacts from Machu Picchu—ceramic vessels, silver statues, jewelry, and human bones—and took them to Yale University for further study, supposedly for 18 months. Yale instead kept the artifacts until 2012, arguing that Peru lacked the infrastructure and systems to care for them. Eliane Karp, an anthropologist and wife of former Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo, accused Yale of profiting from Peru's cultural heritage. Many of the articles were exhibited at Yale's Peabody Museum.

In 2006, Yale returned some pieces but kept the rest, claiming this was supported by federal case law of Peruvian antiquities.[80] In 2007, Peru and Yale had agreed on a joint traveling exhibition and construction of a new museum and research center in Cusco advised by Yale. Yale acknowledged Peru's title to all the objects, but would share rights with Peru in the research collection, part of which would remain at Yale for continuing study.[81] In November 2010, Yale agreed to return the disputed artifacts.[82] The third and final batch of artifacts was delivered November 2012.[83] The artifacts are permanently exhibited at the Museo Machu Picchu, La Casa Concha ("The Shell House"), close to Cusco's colonial center. Owned by the National University of San Antonio Abad del Cusco, La Casa Concha also features a study area for local and foreign students.

In media

Motion pictures

The Paramount Pictures film Secret of the Incas (1955), with Charlton Heston and Ima Sumac, was filmed on location at Cusco and Machu Picchu, the first time that a major Hollywood studio filmed on site. Five hundred indigenous people were hired as extras in the film.[84]

The opening sequence of the film Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) was shot in the Machu Picchu area and on the stone stairway of Huayna Picchu.[85]

Machu Picchu was featured prominently in the film The Motorcycle Diaries (2004), a biopic based on the 1952 youthful travel memoir of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara.[86]

The NOVA television documentary "Ghosts of Machu Picchu" presents an elaborate documentary on the mysteries of Machu Picchu.[87]

Multimedia artist Kimsooja used footage shot near Macchu Picchu in the first episode of her film series Thread Routes, shot in 2010.[88]

Music

The song "Kilimanjaro", from the South Indian Tamil film Enthiran (2010), was filmed in Machu Picchu.[89] The sanction for filming was granted only after direct intervention from the Indian government.[90][91]

Panoramic views

.jpg)

See also

- List of archaeological sites in Peru

- Salkantay Trek – alternative trek to Machu Picchu

- The Chilean Inca Trail

- Iperu, tourist information and assistance

- Kuelap

- Lares trek, an alternative route to that of the Inca Trail

- List of archaeoastronomical sites by country

- Putucusi, neighboring mountain

- Tourism in Peru

- Caral

- Religion in the Inca Empire

- Paleohydrology

References

- Jarus, Owen (31 August 2012). "Machu Picchu: Facts & History - Abandonment of Machu Picchu". Live Science. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- escale.minedu.gob.pe – UGEL map of the Urubamba Province (Cusco Region)

- Carlotto et al. 2009

- "Machu Picchu". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- "Machu Picchu". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- BBC – Editors. "How to say: Machu Picchu". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Pronounced without the /k/ by most Spanish speakers, but pronounced as spelled by experts, for example in Netflix's Perú: Tesoro escondido.

- Nonato Rufino Chuquimamani Valer, Carmen Gladis Alosilla Morales, Victoria Choque Valer: Qullaw Qichwapa Simi Qullqan. Lima, 2014 p. 70

- Davey 2001.

- "Creating Global Memory". New7Wonders of the World. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe, Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, Quechua – Castellano, Castellano – Quechua.

- Luciano, Pellegrino A. (2011). "Where are the Edges of a Protected Area? Political Dispossession in Machu Picchu, Peru". Conservation and Society. 9 (1): 35–41. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.79186. JSTOR 26393123.

- Burger, Richard L.; Salazar, Lucy C. (2004). Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300097634.

- "Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Bingham, Hiram (1952). Lost City of the Incas. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 112–135. ISBN 978-1-84212-585-4.

- McNeill, William (2010). Plagues and Peoples. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-77366-1.

- Turner, Bethany L. (2010). "Variation in Dietary Histories Among the Immigrants of Machu Picchu: Carbon and Nitrogen Isotope Evidence". Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. 42 (2): 515–534. doi:10.4067/s0717-73562010000200012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017 – via Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Sistema de Información Cientifica Redalyc.

- Turner, Bethany L.; Armelagos, George J. (1 September 2012). "Diet, residential origin, and pathology at Machu Picchu, Peru". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 149 (1): 71–83. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22096. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 22639369.

- Morales, M.; Barberena, R.; Belardi, J.B.; Borrero, L.; Cortegoso, V.; Durán, V.; Guerci, A.; Goñi, R.; Gil, A.; Neme, G.; Yacobaccio, H.; Zárate, M. (2009). "Reviewing human-environment interactions in arid regions of southern South America during the past 3000 years". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 281 (3–4): 283–295. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.09.019.

- Malpass, Michael A. (2009). Daily Life in the Inca Empire, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35549-3.

- Brown, Jeff L. (January 2001). "Rediscovering the lost city". Civil Engineering; New York. 71: 32–39. ProQuest 228471133.

- Kenneth Wright

- Kenneth R Wright

- Kenneth R Wright

- Wright & Valencia Zegarra, p. 1.

- Wright & Valencia Zegarra 2001, p. 1.

- Dan Collyns (6 June 2008). "Machu Picchu ruin 'found earlier'". BBC News.;Michael Marshall (7 June 2008). "Incan lost city looted by German businessman". New Scientist.

- Romero, Simon (7 December 2008). "Debate Rages in Peru: Was a Lost City Ever Lost?".

- Olson, David M.; Dinerstein, Eric; Wikramanayake, Eric D.; Burgess, Neil D.; Powell, George V. N.; Underwood, Emma C.; d'Amico, Jennifer A.; Itoua, Illanga; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933–938. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2.

- Bingham 2010.

- "Yale Expedition to Peru". Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia. 10. 1912. pp. 134–136.

- Rodriguez-Camilloni, Humberto (2009). "Reviewed Work: Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas by Richard L Burger, Lucy C. Salazar". Journal of Latin American Geography. 8 (2): 230–232. doi:10.1353/lag.0.0051. JSTOR 25765271.

- Gordon, Robert and John Rutledge 1984 Bismuth Bronze from Machu Picchu, Peru. American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC. p. 585

- Fellman, Bruce (December 2002). "Rediscovering Machu Picchu". Yale Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Salvatore, Ricardo Donato (2003). "Local versus Imperial Knowledge: Reflections on Hiram Bingham and the Yale Peruvian Expedition". Nepantla: Views from South. 4 (1): 67–80.

- Hoffman, Barbara T. (2006). Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy and Practice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85764-2.

- Gaither, Catherine; Jonathan Kent; Victor Sanchez; Teresa Tham (June 2008). "Mortuary Practices and Human Sacrifice in the Middle Chao Valley of Peru: Their Interpretation in the Context of Andean Mortuary Patterning". Latin American Antiquity. 19 (2): 107, 115, 119 [115]. doi:10.1017/S1045663500007744.

- Hill, Michael (2010). "Myth, Globalization, and Mestizaje in New Age Andean Religion: The Intic Churincuna (Children of the Sun) of Urubamba, Peru". Ethnohistory. 57 (2): 263, 273–2m75. doi:10.1215/00141801-2009-063.

- Wright & Valencia Zegarra, p. ix.

- Davies 1997, p. 163.

- Wright, Valencia Zegarra & Crowley 2000b, p. 2.

- Bordewich, Fergus (March 2003). "Winter Palace". Smithsonian: 110. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Longhena 2010, p. 252.

- Wright & Valencia Zegarra, p. 8.

- "Computer Modeling of Heritage Resources".

- Dearborn, D.S.P.; White, R.E. (1983). "The "Torreon" of Machu Picchu as an Observatory". Archaeoastronomy. 14 (5): S37. Bibcode:1983JHAS...14...37D.

- Krupp, Edwin (1994). Echoes of the Ancient Skies. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-0-486-42882-6.

- Doig 2005.

- Amao, Albert (2012). The Dawning of the Golden Age of Aquarius: Redefining the Concepts of God, Man, and the Universe. AuthorHouse. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4685-3752-9. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Dearborn, Schreiber & White 1987, p. 346.

- Dearborn, Schreiber & White 1987, pp. 349–51.

- Dearborn, Schreiber & White 1987, p. 349..

- Menegat, Rualdo. "Machu Picchu: Ancient Incan sanctuary intentionally built on faults". ScienceDaily, Brazil's Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Tripcevich, Nicholas; Vaughn, Kevin J. (2012). Mining and quarrying in the Ancient Andes : sociopolitical, economic, and symbolic dimension. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 52. ISBN 9781461452003.

In some cases, such as Machu Picchu, rock was quarried on site.

- Wright & Valencia Zegarra 2000.

- Burger & Salazar 2004.

- "Galería de Fotos Camino Inca". Archived from the original on 7 February 2016.

- "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Cusco: Llegada de visitantes al Santuario Histórico de Machu Picchu". MINCETUR. December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Bridge stirs the waters in Machu Picchu". BBC News Online. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Global Sacred Lands: Machu Picchu Sacredland.org, Sacred Land Film Project.

- "Peru to construct cable car system in Machu Picchu". Perú Reports. 16 September 2018. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Peru bans flights over Inca ruins", BBC News Online, 8 September 2006

- Collyns, Dan (8 September 2006). "Peru bans flights over Inca ruins". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- Brooke, Chris (19 September 2013). "Father killed by altitude sickness on dream trip to Machu Picchu". news.com.au. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "US Tourist Dies in Fall While Hiking the Inca Trail Near Machu Picchu". Fox News Latino. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Chase, Rachel. "Peru: German tourist dies while trekking Inca Trail". Peru this Week. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Bates, Stephen (26 January 2010). "Stranded tourists await rescue from Machu Picchu". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Johanson, Mark (28 March 2013). "World's Most Controversial Tourist Attractions". International Business Times. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Liu, Evie (20 March 2014). "Peru to Tourists: 'Stop getting naked at Machu Picchu!'". CNN. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- BBC, jhayzee27 (29 January 2010). "Machu Picchu Airlift Rescues 1,400 Tourists". Disaster Alert Network LLC. UBAlert. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- travel staff, Seattle Times (5 February 2010). "Machu Picchu to reopen earlier than expected after storms". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "Machu Picchu New Entrance Rules", Peru Guide (the only). 18 December 2011

- New entrance times for Machu Picchu 2019, 11 November 2018, retrieved 26 December 2018

- "GHF". Global Heritage Fund. 8 June 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Martineau, Kim (14 March 2006). "Peru Presses Yale on Relics". Hartford Courant.

- Mahony, Edmund H. (16 September 2007). "Yale To Return Incan Artifacts". Hartford Courant.

- "Peru's president: Yale agrees to return Incan artifacts". CNN. 20 November 2010.

- Zorthian, Julia. "Yale returns final Machu Picchu artifacts". Yale Daily News. Yale University. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "Production Notes – Secret of the Incas". TCM Database.

- Herzog 2002.

- Excerpted Clip of Machu Picchu from the film The Motorcycle Diaries directed by Walter Salles, distributed by Focus Features, 2004

- Ghosts of Machu Picchu on IMDb

- Womeninthearts (9 September 2014). "Artist Spotlight: Kimsooja's Threads of Culture". Broadstrokes.

- "Endhiran The Robot : First Indian movie to shoot at Machu Pichu". One India. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- "Enthiran beats James Bond". Behindwoods. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- Lahiri, Tripti (1 October 2010). "Machu Picchu Welcomes Rajnikanth and India". WSJ blog. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

Bibliography

- Bingham, Hiram (2010). Lost City of the Incas. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86533-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bingham, Hiram (1922). "Inca Land: explorations in the highlands of Peru". Nature. 111 (2794): 665. Bibcode:1923Natur.111S.665.. doi:10.1038/111665c0. hdl:2027/gri.ark:/13960/t9p31w18z. OCLC 248230298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bingham, Hiram (1979) [1930]. Machu Picchu, a citadel of the Incas. New York: Hacker Art Books. ISBN 978-0-87817-252-8. OCLC 6579761.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burger, Richard; Salazar, Lucy, eds. (2004). Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09763-4. OCLC 52806202.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlotto, V.; Cardenas, J.; Fidel, L. (2009). "La Geologia, evolucion geomorfologica y geodinamica externa de la ciudad Inca de Machupicchu, Cusco-Perù". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 65 (4): 725–747.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Nigel (1997). The Ancient Kingdoms of Peru. London and New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-023381-0. OCLC 37552622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 10 January 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, Kenneth R.; Valencia Zegarra, Alfredo (2000). Machu Picchu: A Civil Engineering Marvel. Reston, Virginia: ASCE Press (American Society of Civil Engineers). ISBN 978-0-7844-7052-7. OCLC 43526790.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, Kenneth R.; Valencia Zegarra, Alfredo & Crowley, Christopher M. (May 2000). "Completion Report to Instituto Nacional de Cultura on Archaeological Exploration of the Inca Trail on the East Flank of Machu Picchu and on Palynology of Terraces Part 1" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Wright, Kenneth R.; Valencia Zegarra, Alfredo & Crowley, Christopher M. (May 2000). "Completion Report to Instituto Nacional de Cultura on Archaeological Exploration of the Inca Trail on the East Flank of Machu Picchu and on Palynology of Terraces Part 2" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Burger, Richard L.; Salazar, Lucy C. (2004). Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09763-4.

- Wright, Kenneth R.; Valencia Zegarra, Alfredo & Crowley, Christopher M. (May 2000). "Completion Report to Instituto Nacional de Cultura on Archaeological Exploration of the Inca Trail on the East Flank of Machu Picchu and on Palynology of Terraces Part 3" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, Ruth; Valencia Zegarra, Alfredo (2004) [2001]. The Machu Picchu Guidebook: A self-guided tour. Big Earth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55566-327-8. OCLC 53330849.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nava, Pedro Sueldo (2000). A Walking Tour of Machupicchu. Editoral Cumbre. OCLC 2723003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davey, Peter (October 2001). "Outrage: Rebuilding Machu Picchu, Peru". The Architectural Review. Retrieved 7 June 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dearborn, David S. P.; Schreiber, Katharina J.; White, Raymond E. (1 January 1987). "Intimachay: A December Solstice Observatory at Machu Picchu, Peru". American Antiquity. 52 (2): 346–352. doi:10.2307/281786. JSTOR 281786.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McNeill, William (2010). Plagues and Peoples. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-77366-1.

- Longhena, Maria (2007). The Incas and Other Ancient Andean Civilizations. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-1-4351-0003-9.

- Doig, Federico Kauffmann (2005). Machu Picchu: tesoro inca. ICPNA, Instituto Cultural Peruano Norteamericano.

Further reading

- Frost, Peter; Blanco, Daniel; Rodríguez, Abel & Walker, Barry (1995). Machu Picchu Historical Sanctuary. Lima: Nueves Imágines. OCLC 253680819.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kops, Deborah (2008). Machu Picchu. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-7584-9.

- MacQuarrie, Kim (2007). The Last Days of the Incas. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6049-7. OCLC 77767591.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magli, Giulio (2009). "At the other end of the sun's path: A new interpretation of Machu Picchu". Nexus Network Journal – Architecture and Mathematics. 12 (2010): 321–341. arXiv:0904.4882. Bibcode:2009arXiv0904.4882M. doi:10.1007/s00004-010-0028-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reinhard, Johan (2007). Machu Picchu: Exploring an Ancient Sacred Center. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA. ISBN 978-1-931745-44-4. OCLC 141852845.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice, Mark (2018). Making Machu Picchu: The Politics of Tourism in Twentieth-Century Peru (U of North Carolina Press) online review

- Richardson, Don (1981). Eternity in their Hearts. Ventura, CA: Regal Books. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-8307-0925-0. OCLC 491826338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian givers: how the Indians of the Americas transformed the world. New York: Fawcett Columbine. ISBN 978-0-449-90496-1. OCLC 474116190.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- es:Daniel Eisenberg (1989). "Machu Picchu and Cuzco", Journal of Hispanic Philology, vol. 13, pp. 97–101.

- Herzog, Werner; Cronin, Paul (2002). Herzog on Herzog. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-571-20708-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Machu Picchu. |

- Geology of Machu Picchu

- UNESCO – Machu Picchu (World Heritage)

- Wright Paleohydrological Institute with reports on water management at Machu Picchu

- Profile at protectedplanet.net

Images