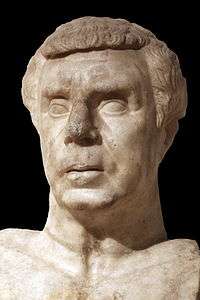

Lucius Munatius Plancus

Lucius Munatius Plancus (c. 87 BC in Tibur – c. 15 BC in Gaeta) was a Roman senator, consul in 42 BC, and censor in 22 BC with Lucius Aemilius Lepidus Paullus. Along with Talleyrand eighteen centuries later, he is one of the classic historical examples of men who have managed to survive very dangerous circumstances by constantly shifting their allegiances.

Early career

Plancus's early career is rather unclear, and we know little about him, only that he was the namesake of his father, grandfather and great-grandfather. He was part of Julius Caesar's officer corps during the conquest of Gaul and the civil war against Pompey. His funerary inscription attests that he founded the cities of Augusta Raurica (44 BC) and Lugdunum (Lyon) (43 BC)[1] and in June 43 BC, some letters attest to his passage through the village of Cularo (present Grenoble) in the Dauphiné Alps.[2]

Civil war

When Caesar was assassinated on 15 March 44 BC, Plancus was the Proconsul of Gallia Comata. In the political confusion that followed, Plancus revealed himself as a master of non-committance in his extensive correspondence with Cicero. While Antony besieged Decimus Brutus in Mutina, Plancus wrote to the Senate in March 43 about his loyalty to the commonwealth, as well as of his need to disguise this during the consolidation of his position.[3] Thereafter he claimed that he would be unable to assist Brutus, as Marcus Aemilius Lepidus would block the movement of his troops: as he wrote to Cicero in May, “I should be ashamed to chop and change in my letters, were it not that these things depend on the fickleness of another person...Lepidus”.[4] After crossing the Alps into Gaul, apparently in support of Brutus, he repeatedly held back his troops from combat on the grounds that the time was not ripe;[5] and once Lepidus, Antony and Octavian formed the Second Triumvirate, he abandoned Brutus (and Cicero) to their fates by joining decisively with their opponent, Antony.[6] Thereafter he held the consulship with Lepidus in 42 BC, and became proconsul of Asia in about 40 BC.

During Mark Antony's expedition (36 BC) to Armenia and Parthia, to avenge Crassus' death (17 years earlier) he was proconsul of Syria. But when Antony's campaign against the Parthians failed, he chose to leave him and join Octavian. According to Suetonius, Plancus was the one who suggested Octavian adopt the title "Augustus" rather than be called Romulus as a "second founder of Rome."[7]

Under Augustus

On 16 Jan. 27 BC, he proposed the title Augustus "revered one" be granted to the young princeps senatus.

In 22 BC, Augustus appointed him and Aemilius Lepidus Paullus to fill the office of censor.[8][9][10] Their censorship is famous not for any remarkable deeds, but because it was the last time that such magistrates were appointed. According to Velleius Paterculus' Roman history,[11] it was a shame for both of the senators:

. . . the censorship of Plancus and Paullus, which, exercised as it was with mutual discord, was little credit to themselves or little benefit to the state, for the one lacked the force, the other the character, in keeping with the office; Paullus was scarcely capable of filling the censor's office, while Plancus had only too much reason to fear it, nor was there any charge which he could make against young men, or hear others make, of which he, old though he was, could not recognize himself as guilty . . .

In Suetonius' Life of Nero,[12] we read that the emperor Nero's grandfather, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, whose wife was Antonia Major, daughter of Mark Antony, "was haughty, extravagant, and cruel, and when he was only an aedile, forced the censor Lucius Plancus to make way for him on the street"; the story seems to hint at the poor reputation Plancus held after his censorship.

Legacy

Plancus is one of the very few important Roman historical figures whose tomb has survived and is identifiable, although his body has long since vanished. The Mausoleum of Plancus, a massive cylindrical tomb now much restored (and consecrated to the Virgin Mary in the late 19th century), is in Gaeta, on a hill overlooking the sea: it houses a small permanent exhibit in honor of him.

Plancus' children included one son and one daughter. His son was Lucius Munatius Plancus (ca 45 BC - aft. 14), consul in AD 13 and legate in 14, who married Aemilia Paulla, daughter of Aemilius Lepidus Paullus and wife Cornelia Lentula. In AD 14 the son went to Germany to help suppress the Rhine legions' mutiny with little success.[13] Plancus' daughter Munatia Plancina (ca 35 BC - aft. 20) married the infamous Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, and they had two sons, Gnaeus and Marcus Piso. Plancina and her husband were accused of poisoning Germanicus.[14] In Syria, she offended common sensibility by attending cavalry exercises and hired a notorious poisoner.[15] After the death of Germanicus, Piso and Plancina first tried to take back control of the province, then slowly returned to Rome, where they were put on trial for fomenting civil war and for poisoning Germanicus. Eventually Livia intervened to save Plancina and she was pardoned. Many years later in AD 34 she was again prosecuted and driven to suicide.[16] Her two sons survived her. Gnaeus Piso had to change his name to Lucius Piso, but later became governor of Africa in AD 39 under Caligula.[17] The charges against Marcus Piso were dismissed by Tiberius.[18]

References

- Funerary inscription of Lucius Munatius Plancus CIL X, 6087 Uchicago.edu

- Cicero, Ad Familiares, X, 17, 18 & 23

- D R Shackleton Bailey trans., Cicero’s Letters to his Friends (Atlanta 1988) p. 552-4

- D R Shackleton Bailey trans., Cicero’s Letters to his Friends (Atlanta 1988) p. 580

- D R Shackleton Bailey trans., Cicero’s Letters to his Friends (Atlanta 1988) p. 634

- D R Shackleton Bailey trans., Cicero’s Letters to his Friends (Atlanta 1988) p. 812

- (Suet. Aug. 7)

- Suet. Aug. 37

- Claud. 16

- Dio, liv.2

- (II.95)

- (ch. 4)

- Tacitus Annals, 1.39

- Tacitus Annals, 2.43.4, 2.74.2, 3.8-18; Dio 57.18.9

- Tacitus Annals, 2.55.5, 2.74.2

- Tacitus Annals, 6.24.4; Dio 58.22.5

- Dio 59.20.7

- Tacitus Annals, 3.17-18

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus |

Consul of the Roman Republic with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus 42 BC |

Succeeded by Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus and Lucius Antonius |