Lodge Bill

The Lodge Bill or Federal Elections Bill or Lodge Force Bill of 1890 was a bill drafted by Representative Henry Cabot Lodge (R) of Massachusetts, and sponsored in the Senate by George Frisbie Hoar; it was endorsed by President Benjamin Harrison. The bill would have authorized the federal government to ensure that elections were fair. In particular, it would have allowed federal circuit courts (after being petitioned by a small number of citizens from any precinct) to appoint federal supervisors of congressional elections. Said supervisors would have many duties, including: attending elections, inspecting registration lists, verifying doubtful voter information, administering oaths to challenged voters, stopping illegal aliens from voting, and certifying the vote count.[1]

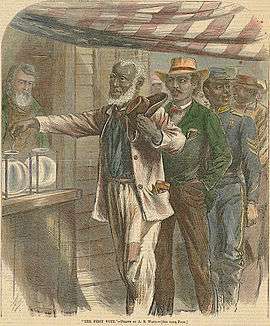

The bill was created primarily to enforce the ability of blacks, predominantly Republican at the time, to vote in the South, as provided for in the constitution. The Fifteenth Amendment already formally guaranteed that right, but white southern Democrats had passed laws related to voter registration and electoral requirements, such as requiring payment of poll taxes and literacy tests (often waived if the prospective voter's grandfather had been a registered voter, the "grandfather clause"), that effectively prevented blacks from voting. That year Mississippi passed a new constitution that disfranchised most blacks, and other states would soon follow the "Mississippi plan".

After passing the House by just six votes,[2] the Lodge bill was successfully filibustered in the Senate, with little action by the President of the Senate, Vice President Levi P. Morton, because Silver Republicans in the West traded it away for Southern support of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and Northern Republicans traded it away for Southern support of the McKinley Tariff.[3][4]

Julius Caesar Chappelle (1852–1904) was among the earliest black Republican legislators in the United States, representing Boston and serving from 1883–1886. In 1890, Chappelle gave a political speech for the right of blacks to vote at an "enthusiastic" meeting at Boston's Faneuil Hall to support the federal elections bill. He was featured in a front page article in The New York Age newspaper covering his support of the Lodge bill.[5]

15th Amendment

The 15th Amendment to the US Constitution states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” [6] Its purpose was to acknowledge African American men’s voting rights.[7] After the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, African Americans were subjected to voting restrictions in certain states. Disenfranchisement of African Americans came in various forms, such as poll taxes, literacy tests, white primaries, and grandfather clauses.

Aftermath

The failure of the passage of the bill led to an increase in voter suppression until the during Civil Rights Movement when President Lyndon Johnson passed the Voting Right Act of 1965. The purpose was to outlaw the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting.[8] The Act enforced the 15th Amendment almost a century after it was ratified. With section five it got rid of provisions that allowed disenfranchisement of African Americans in the United State. It stated that "Under Section 5, jurisdictions covered by these special provisions could not implement any change affecting voting until the Attorney General or the United States District Court for the District of Columbia determined that the change did not have a discriminatory purpose and would not have a discriminatory effect. In addition, the Attorney General could designate a county covered by these special provisions for the appointment of a federal examiner to review the qualifications of persons who wanted to register to vote. Further, in those counties where a federal examiner was serving, the Attorney General could request that federal observers monitor activities within the county's polling place.[9] The Lodge Bill was a precursor of the various Civil Right legislation that followed.

See also

References

- Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, Basic Books, 2000, p. 86.

- "Black Americans in Congress: The Negroes' Temporary Farewell". Office of the Historian, House of Representatives. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- Louis Hacker and Benjamin Kendrick The United States Since 1865(New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1949), 74

- Wendy Hazard, "Thomas Brackett Reed, Civil Rights, and the Fight for Fair Elections," Maine History, March 2004, Vol. 42 Issue 1, pp 1–23

- "At the Cradle of Liberty: Enthusiastic Endorsement of the Elections Bill," The New York Age, front page, Saturday, August 9, 1890.

- "Constitution of the United States, Fifteenth Amendment". Congress.gov. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments". National Park Service (nps.gov). USA.gov. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Our Documents - Voting Rights Act (1965)". www.ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- "History Of Federal Voting Rights Laws". www.justice.gov. 2015-08-06. Retrieved 2020-04-09.