List of eulipotyphlans of the Caribbean

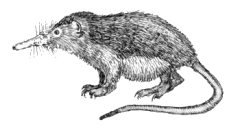

The Caribbean region is home to two unique families of the mammalian order Eulipotyphla (incorporating the now defunct order Soricomorpha), which also includes the hedgehogs, gymnures shrews, moles and desmans. Only one Caribbean family, that of the solenodons, is still extant; the other, Nesophontidae, became extinct within the last few centuries.

For the purposes of this article, the "Caribbean" includes all islands in the Caribbean Sea (except for small islets close to the mainland) and the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, and Barbados, which are not in the Caribbean Sea but biogeographically belong to the same Caribbean bioregion.

Overview

About fifteen species of Caribbean eulipotyphlans are known to have existed during the Quaternary, but not all Nesophontes species are universally accepted as valid.[1] However, most of these, including all Nesophontes, are now extinct, and the two surviving solenodons are classified as "endangered".[2]

The interrelationships of the two Caribbean genera remain unclear. Similarities in skull morphology have led some to propose close affinities between the two, but differences in characters of the teeth are evidence against a close relationship.[3] DNA evidence suggests that Solenodon is sister to a clade of shrews, moles, and erinaceids, with a molecular clock providing evidence that the split from the other families occurred in the Cretaceous period, late in the Mesozoic era.[4] How they came to the Antilles is unknown; they may have arrived either via overwater dispersal or via some sort of land bridge from North America, South America, or even Africa, and Nesophontes and Solenodon may have different origins.[5]

The genera of Caribbean eulipotyphlans are classified as follows:[6]

- Order Eulipotyphla

- Family Nesophontidae: Nesophontes

- Family Solenodontidae: Solenodon

- Unidentified genus[7]

Cuba

Cuba, the largest of the Antilles, also has the largest inventory of eulipotyphlans, including five members of Nesophontes and two solenodons.

- Nesophontes longirostris is known from cave deposits of uncertain age.[8]

- Nesophontes major is known from cave deposits of uncertain age.[8]

- Nesophontes micrus, the most widespread Nesophontes, is known from remains from Cuba dated to the 14th century CE.[8]

- Nesophontes submicrus is known from cave deposits of uncertain age.[9]

- Nesophontes superstes, a large Nesophontes, is known from a single mandible that was found on the surface of a cave deposit together with Rattus, suggesting recent survival.[10]

- Solenodon arredondoi is known from Late Pleistocene deposits in western Cuba.[11]

- Solenodon cubanus, the only surviving Cuban solenodon, has been confirmed only from eastern Cuba as a living animal, but there are several fossil records in the western part of the island.[12]

- Some fossil cave samples from several localities represent solenodons that are larger than S. cubanus, but too small for S. arredondoi. They have been identified as Solenodon cf. cubanus.[13]

Isla de la Juventud

Isla de la Juventud is a large island south of Cuba.

- Nesophontes micrus has been recorded from the island.[8]

Cayman Islands

Two extinct undescribed species of Nesophontes are known from several cave deposits on the Cayman Islands, a British archipelago south of Cuba. The two are similar in morphology, but the species from Grand Cayman is larger than the one from Cayman Brac. They are closely related to each other and to the Cuban–Hispaniolan species N. micrus. The oldest record is from the latest Pleistocene, but they probably arrived there earlier in the Pleistocene, if not in the Pliocene.[14] In the youngest layers of several deposits, Nesophontes is found together with introduced Rattus, indicating that its extinction occurred relatively recently.[15]

Hispaniola

Hispaniola is the second largest of the Antilles. It is divided into Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

- Nesophontes hypomicrus has been found together with Rattus and remains from a cave in the Dominican Republic have been dated to the 13th century CE.[8]

- Nesophontes micrus has also been recorded from Hispaniola.[8]

- Nesophontes paramicrus has been found together with remains of Rattus; some bones from a cave in Haiti have been dated to the 14th century CE.[8]

- Nesophontes zamicrus has been found together with Rattus; some remains have been radiocarbon-dated to the 13th century CE.[10]

- Solenodon marcanoi is known from late Quaternary fossil deposits in southern Haiti and the southwestern Dominican Republic.[16]

- Solenodon paradoxus, one of the two living solenodons, is known both as a living animal and from fossil deposits throughout much of the island, except for northern Haiti.[17] Separate subspecies occur in the northern (S. p. paradoxus) and southern highlands (S. p. woodi).[18]

- Some chest vertebrae and associated ribs of a mammal, probably a solenodontid, have been found in amber in the Dominican Republic. These are probably not older than the late Oligocene. The animal would have been about the size of Nesophontes, with an estimated body mass of 150 grams (5.3 oz).[7]

Gonâve

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is the smallest and easternmost of the Greater Antilles.

Vieques

Vieques is the largest island associated with Puerto Rico; it is located east of the main island.

Saint John

Saint John is one of the main islands of the northern United States Virgin Islands.

Saint Thomas

Saint Thomas is one of the main islands of the northern United States Virgin Islands.

See also

References

- Hutterer, 2005, p. 220

- IUCN, 2015

- Whidden and Asher, 2001, p. 237

- Roca et al., 2004

- Whidden and Asher, 2001, pp. 248–249

- Hutterer, 2005

- MacPhee and Grimaldi, 1996

- Hutterer, 2005, p. 221

- Hutterer, 2005, pp. 220–221

- Hutterer, 2005, p. 222

- Ottenwalder, 2001, fig. 19

- Ottenwalder, 2001, fig. 17

- Ottenwalder, 2001, p. 306

- Morgan, 1994b, pp. 485–487

- Morgan, 1994a, p. 457

- Ottenwalder, 2001, fig. 18

- Ottenwalder, 2001, fig. 16

- Ottenwalder, 2001, p. 299

- Turvey et al., 2007, table 1

- Ottenwalder, 2001, p. 253

- MacPhee et al., 1999, p. 7

Literature cited

- Hutterer, R. (2005). "Order Soricomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 220–231. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on June 20, 2015.

- MacPhee, R.D.E.; Grimaldi, D.A. (1996). "Mammal bones in Dominican amber". Nature. 380 (6574): 489–490. doi:10.1038/380489b0.

- MacPhee, R.D.E.; Flemming, C.; Lunde, D.P. (1999). "Last occurrence" of the Antillean insectivoran Nesophontes: New radiometric dates and their interpretation. American Museum Novitates 3261:1–20.

- Morgan, G.S. (1994a). "Mammals of the Cayman Islands". In Brunt, M.A.; Davies, J.E. (eds.). The Cayman Islands: Natural History and Biogeography. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 435–463. ISBN 978-94-011-0904-8. OCLC 28586438.

- Morgan, G.S. (1994b). "Late Quaternary fossil vertebrates from the Cayman Islands". In Brunt, M.A.; Davies, J.E. (eds.). The Cayman Islands: Natural History and Biogeography. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 465–508. ISBN 978-94-011-0904-8. OCLC 28586438.

- Ottenwalder, J.A. (2001). "Systematics and biogeography of the West Indian genus Solenodon". In Woods, C.A.; Sergile, F.E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives, Second Edition. Boca Raton, London, New York, and Washington, D.C.: CRC Press. pp. 253–330. doi:10.1201/9781420039481-16. ISBN 978-1-4200-3948-1. OCLC 46240352.

- Roca, A.L.; Bar-Gal, G.K.; Eizirik, E.; Helgen, K.M.; Maria, R.; Springer, M.S.; J. O'Brien, S.; Murphy, W.J. (2004). "Mesozoic origin for West Indian insectivores". Nature. 429 (6992): 649–651. doi:10.1038/nature02597. PMID 15190349.

- Turvey, S.T.; Oliver, J.R.; Narganes Storde, Y.M.; Rye, P. (2007). "Late Holocene extinction of Puerto Rican native land mammals". Biology Letters. 3 (2): 193–196. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0585. PMC 2375922. PMID 17251123.

- Whidden, H.P.; Asher, R.J. (2001). "The origin of the Greater Antillean insectivorans". In Woods, C.A.; Sergile, F.E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives, Second Edition. Boca Raton, London, New York, and Washington, D.C.: CRC Press. pp. 237–252. ISBN 978-1-4200-3948-1. OCLC 46240352.