Linseed oil

Linseed oil, also known as flaxseed oil or flax oil (in its edible form), is a colourless to yellowish oil obtained from the dried, ripened seeds of the flax plant (Linum usitatissimum). The oil is obtained by pressing, sometimes followed by solvent extraction. Linseed oil is a drying oil, meaning it can polymerize into a solid form. Owing to its polymer-forming properties, linseed oil can be used on its own or blended with combinations of other oils, resins or solvents as an impregnator, drying oil finish or varnish in wood finishing, as a pigment binder in oil paints, as a plasticizer and hardener in putty, and in the manufacture of linoleum. Linseed oil use has declined over the past several decades with increased availability of synthetic alkyd resins—which function similarly but resist yellowing.[1]

Linseed oil is an edible oil in demand as a dietary supplement, as a source of α-Linolenic acid, (an omega-3 fatty acid). In parts of Europe, it is traditionally eaten with potatoes and quark. It is regarded as a delicacy due to its hearty taste and ability to improve the bland flavour of quark.[2]

Chemical aspects

Linseed oil is a triglyceride, like other fats. Linseed oil is distinctive for its unusually large amount of α-linolenic acid, which has a distinctive reaction with oxygen in air. Specifically, the fatty acids in a typical linseed oil are of the following types:[3]

- The triply unsaturated α-linolenic acid (51.9–55.2%),

- The saturated acids palmitic acid (about 7%) and stearic acid (3.4–4.6%),

- The monounsaturated oleic acid (18.5–22.6%),

- The doubly unsaturated linoleic acid (14.2–17%).

Having a high content of di- and tri-unsaturated esters, linseed oil is particularly susceptible to polymerization reactions upon exposure to oxygen in air. This polymerization, which is called "drying", results in the rigidification of the material. The drying process can be so exothermic as to pose a fire hazard under certain circumstances. To prevent premature drying, linseed oil-based products (oil paints, putty) should be stored in airtight containers.

Like some other drying oils, linseed oil exhibits fluorescence under UV light after degradation.[4]

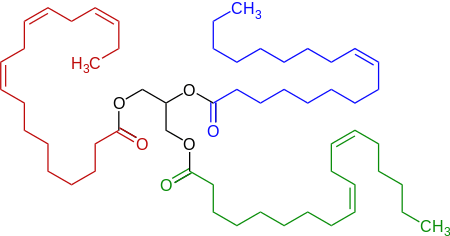

Representative triglyceride found in a linseed oil, a triester (triglyceride) derived of linoleic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, and oleic acid.

Representative triglyceride found in a linseed oil, a triester (triglyceride) derived of linoleic acid, alpha-linolenic acid, and oleic acid.

Uses

Most applications of linseed oil exploit its drying properties, i.e., the initial material is liquid or at least pliable and the aged material is rigid but not brittle. The water-repelling (hydrophobic) nature of the resulting hydrocarbon-based material is advantageous.

Paint binder

Linseed oil is a common carrier used in oil paint. It can also be used as a painting medium, making oil paints more fluid, transparent and glossy. It is available in varieties such as cold-pressed, alkali-refined, sun-bleached, sun-thickened, and polymerised (stand oil). The introduction of linseed oil was a significant advance in the technology of oil painting.

Putty

Traditional glazing putty, consisting of a paste of chalk powder and linseed oil, is a sealant for glass windows that hardens within a few weeks of application and can then be painted over. The durability of putty is owed to the drying properties of linseed oil.

Wood finish

When used as a wood finish, linseed oil dries slowly and shrinks little upon hardening. Linseed oil does not cover the surface as varnish does, but soaks into the (visible and microscopic) pores, leaving a shiny but not glossy surface that shows off the grain of the wood. A linseed oil finish is easily scratched, and easily repaired. Only wax finishes are less protective. Liquid water penetrates a linseed oil finish in mere minutes, and water vapour bypasses it almost completely.[5] Garden furniture treated with linseed oil may develop mildew. Oiled wood may be yellowish and is likely to darken with age. Because it fills the pores, linseed oil partially protects wood from denting by compression.

Linseed oil is a traditional finish for firearm stocks, though very fine finish may require months to obtain. Several coats of linseed oil is the traditional protective coating for the raw willow wood of cricket bats; it is used so that the wood retains some moisture. New cricket bats are coated with linseed oil and knocked-in to perfection so that they last longer.[6] Linseed oil is also often used by billiards or pool cue-makers for cue shafts, as a lubricant/protectant for wooden recorders, and used in place of epoxy to seal modern wooden surfboards.

Additionally, a luthier may use linseed oil when reconditioning a guitar, mandolin, or other stringed instrument's fret board; lemon-scented mineral oil is commonly used for cleaning, then a light amount of linseed oil (or other drying oil) is applied to protect it from grime that might otherwise result in accelerated deterioration of the wood.

Gilding

Boiled linseed oil is used as sizing in traditional oil gilding to adhere sheets of gold leaf to a substrate (parchment, canvas, Armenian bole, etc.) It has a much longer working time than water-based size and gives a firm smooth surface which is adhesive enough in the first 12–24 hours after application to cause the gold to attach firmly to the intended surface.

Linoleum

Linseed oil is used to bind wood dust, cork particles, and related materials in the manufacture of the floor covering linoleum. After its invention in 1860 by Frederick Walton, linoleum, or 'lino' for short, was a common form of domestic and industrial floor covering from the 1870s until the 1970s when it was largely replaced by PVC ('vinyl') floor coverings.[7] However, since the 1990s, linoleum is on the rise again, being considered more environmentally sound than PVC.[8] Linoleum has given its name to the printmaking technique linocut, in which a relief design is cut into the smooth surface and then inked and used to print an image. The results are similar to those obtained by woodcut printing.

Nutritional supplement and food

Raw cold-pressed linseed oil – commonly known as flax seed oil in nutritional contexts – is easily oxidized, and rapidly becomes rancid, with an unpleasant odour, unless refrigerated. Linseed oil is not generally recommended for use in cooking. Alpha linolenic acid (ALA) while bound to flaxseed ALA can withstand temperatures up to 175 °C (350 °F) for two hours.[9]

Food-grade flaxseed oil is cold-pressed, obtained without solvent extraction, in the absence of oxygen, and marketed as edible flaxseed oil. Fresh, refrigerated and unprocessed, linseed oil is used as a nutritional supplement and is a traditional European ethnic food, highly regarded for its nutty flavor. Regular flaxseed oil contains between 57% and 71% polyunsaturated fats (alpha-linolenic acid, linoleic acid).[10] Plant breeders have developed flaxseed with both higher ALA (70%)[10] and very low ALA content (< 3%).[11] The USFDA granted generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status for high alpha linolenic flaxseed oil.[12]

Nutrient content

| Typical fatty acid content | % [13] | % European[14] |

|---|---|---|

| Palmitic acid | 6.0 | 4.0–6.0 |

| Stearic acid | 2.5 | 2.0–3.0 |

| Arachidic acid | 0.5 | 0–0.5 |

| Palmitoleic acid | - | 0–0.5 |

| Oleic acid | 19.0 | 10.0–22.0 |

| Eicosenoic acid | - | 0–0.6 |

| Linoleic acid | 24.1 | 12.0–18.0 |

| Alpha-linolenic acid | 47.4 | 56.0–71.0 |

| Other | 0.5 | - |

Nutrition information from the Flax Council of Canada.[15]

Per 1 tbsp (14 g)

- Calories: 126

- Total fat: 14 g

- Omega-3: 8 g

- Omega-6: 2 g

- Omega-9: 3 g

Flax seed oil contains no significant amounts of protein, carbohydrates or fibre.

Comparison to other vegetable oils

| Type | Processing treatment | Saturated fatty acids | Monounsaturated fatty acids | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Smoke point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[16] | Oleic acid (ω-9) | Total[16] | α-Linolenic acid (ω-3) | Linoleic acid (ω-6) | ω-6:3 ratio | ||||

| Almond oil | |||||||||

| Avocado[18] | 11.6 | 70.6 | 52-66[19] | 13.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 12.5:1 | 250 °C (482 °F)[20] | |

| Brazil nut[21] | 24.8 | 32.7 | 31.3 | 42.0 | 0.1 | 41.9 | 419:1 | 208 °C (406 °F)[22] | |

| Canola[23] | 7.4 | 63.3 | 61.8 | 28.1 | 9.1 | 18.6 | 2:1 | 238 °C (460 °F)[22] | |

| Cashew oil | |||||||||

| Chia seeds | |||||||||

| Cocoa butter oil | |||||||||

| Coconut[24] | 82.5 | 6.3 | 6 | 1.7 | 175 °C (347 °F)[22] | ||||

| Corn[25] | 12.9 | 27.6 | 27.3 | 54.7 | 1 | 58 | 58:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[26] | |

| Cottonseed[27] | 25.9 | 17.8 | 19 | 51.9 | 1 | 54 | 54:1 | 216 °C (420 °F)[26] | |

| Flaxseed/Linseed[28] | 9.0 | 18.4 | 18 | 67.8 | 53 | 13 | 0.2:1 | 107 °C (225 °F) | |

| Grape seed | 10.5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 74.7 | - | 74.7 | very high | 216 °C (421 °F)[29] | |

| Hemp seed[30] | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 82.0 | 22.0 | 54.0 | 2.5:1 | 166 °C (330 °F)[31] | |

| Vigna mungo | |||||||||

| Mustard oil | |||||||||

| Olive[32] | 13.8 | 73.0 | 71.3 | 10.5 | 0.7 | 9.8 | 14:1 | 193 °C (380 °F)[22] | |

| Palm[33] | 49.3 | 37.0 | 40 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 45.5:1 | 235 °C (455 °F) | |

| Peanut[34] | 20.3 | 48.1 | 46.5 | 31.5 | 0 | 31.4 | very high | 232 °C (450 °F)[26] | |

| Pecan oil | |||||||||

| Perilla oil | |||||||||

| Rice bran oil | |||||||||

| Safflower[35] | 7.5 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 12.8 | 0 | 12.8 | very high | 212 °C (414 °F)[22] | |

| Sesame[36] | ? | 14.2 | 39.7 | 39.3 | 41.7 | 0.3 | 41.3 | 138:1 | |

| Soybean[37] | Partially hydrogenated | 14.9 | 43.0 | 42.5 | 37.6 | 2.6 | 34.9 | 13.4:1 | |

| Soybean[38] | 15.6 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 57.7 | 7 | 51 | 7.3:1 | 238 °C (460 °F)[26] | |

| Walnut oil | |||||||||

| Sunflower (standard)[39] | 10.3 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 65.7 | 0 | 65.7 | very high | 227 °C (440 °F)[26] | |

| Sunflower (< 60% linoleic)[40] | 10.1 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 40.1 | 0.2 | 39.8 | 199:1 | ||

| Sunflower (> 70% oleic)[41] | 9.9 | 83.7 | 82.6 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 18:1 | 232 °C (450 °F)[42] | |

| Cottonseed[43] | Hydrogenated | 93.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5:1 | ||

| Palm[44] | Hydrogenated | 88.2 | 5.7 | 0 | |||||

| The nutritional values are expressed as percent (%) by weight of total fat. | |||||||||

Additional uses

- Animal care products

- Bicycle maintenance as a thread fixative, rust inhibitor and lubricant

- Composition ornament for moulded decoration

- Earthen floors

- Animal feeds

- Industrial lubricant

- Leather treatment

- Oilcloth

- Particle detectors[45]

- Textiles

- Wood preservation (including as an active ingredient of Danish oil)

- Cookware seasoning

Modified linseed oils

Stand oil

Stand oil is generated by heating linseed oil near 300 °C for a few days in the complete absence of air. Under these conditions, the polyunsaturated fatty esters convert to conjugated dienes, which then undergo Diels-Alder reactions, leading to crosslinking. The product, which is highly viscous, gives highly uniform coatings that "dry" to more elastic coatings than linseed oil itself. Soybean oil can be treated similarly, but converts more slowly. On the other hand, tung oil converts very quickly, being complete in minutes at 260 °C. Coatings prepared from stand oils are less prone to yellowing than are coatings derived from the parent oils.[46]

Boiled linseed oil

Boiled linseed oil is a combination of raw linseed oil, stand oil (see above), and metallic dryers (catalysts to accelerate drying).[46] In the Medieval era, linseed oil was boiled with lead oxide (litharge) to give a product called boiled linseed oil.[47] The lead oxide forms lead "soaps" (lead oxide is alkaline) which promotes hardening (polymerisation) of linseed oil by reaction with atmospheric oxygen. Heating shortens its drying time.

Raw linseed oil

Raw linseed oil is the base oil, unprocessed and without driers or thinners. It is mostly used as a feedstock for making a boiled oil. It does not cure sufficiently well or quickly to be regarded as a drying oil.[48] Raw linseed is sometimes used for oiling cricket bats to increase surface friction for better ball control.[49] It was also used to treat leather flat belt drives to reduce slipping.

Spontaneous combustion

Rags soaked with linseed oil stored in a pile are considered a fire hazard because they provide a large surface area for rapid oxidation of the oil. The oxidation of linseed oil is an exothermic reaction, which accelerates as the temperature of the rags increases. If heat accumulation exceeds the rate of heat dissipation into the environment, the temperature will increase and may eventually become hot enough to make the rags spontaneously combust.[50]

In 1991, One Meridian Plaza, a high rise in Philadelphia, was severely damaged in a fire, in which three firefighters perished, thought to be caused by rags soaked with linseed oil.[51]

Notes

Further reading

- Knight, William A.; Mende, William R. (2000). Staining and Finishing for Muzzleloading Gun Builders. privately published. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30.

References

- Jones, Frank N. (2003). "Alkyd Resins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_409. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- "Rezept Kartoffeln mit Leinoel".

- Vereshchagin, A. G.; Novitskaya, Galina V. (1965). "The triglyceride composition of linseed oil". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 42 (11): 970–974. doi:10.1007/BF02632457. PMID 5898097.

- E. René de la Rie, Fluorescence of Paint and Varnish Layers (Part II), Studies in Conservation Vol. 27, No. 2 (1982), pp65-69

- Flexner, Bob. Understanding Wood Finishing. Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 2005, p. 75.

- James Laver, "Preparing Your Cricket Bat - Knocking In," ABC of Cricket.

- S. Diller and J. Diller, Craftsman's Construction Installation Encyclopedia, Craftsman Book Company, 2004, p. 503

- Julie K. Rayfield, The Office Interior Design Guide: An Introduction for Facility and Design Professionals, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, p. 209

- Chen, Z. Y.; Ratnayake, W. M. N.; Cunnane, S. C. (1994). "Oxidative stability of flaxseed lipids during baking". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 71 (6): 629–632. doi:10.1007/BF02540591.

- Diane H. Morris (2007). "Chapter 1: Description and Composition of Flax; In: Flax – A Health and Nutrition Primer". Flax Council of Canada. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Thompson, Lilian U.; Cunnane, Stephen C., eds. (2003). Flaxseed in human nutrition (2nd ed.). AOCS Press. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-1-893997-38-7.

- "U.S. FDA/CFSAN Agency Response Letter GRAS Notice No. GRN 00256". U.S. FDA/CFSAN. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- "Linseed" (PDF). Interactive European Network for Industrial Crops and their Applications. October 14, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Fettwissenschaft (see 'Leinöl Europa': Fettsäurezusammensetzung wichtiger pflanzlicher und tierischer Speisefette und -öle Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- "Flax - A Healthy Food". Flax Council of Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- "US National Nutrient Database, Release 28". United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. All values in this table are from this database unless otherwise cited.

- "Fats and fatty acids contents per 100 g (click for "more details"). Example: Avocado oil (user can search for other oils)". Nutritiondata.com, Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, Standard Release 21. 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2017. Values from Nutritiondata.com (SR 21) may need to be reconciled with most recent release from the USDA SR 28 as of Sept 2017.

- "Avocado oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Feramuz Ozdemir; Ayhan Topuz (May 2003). "Changes in dry matter, oil content and fatty acids composition of avocado during harvesting time and post-harvesting ripening period" (PDF). Elsevier. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Marie Wong; Cecilia Requejo-Jackman; Allan Woolf (April 2010). "What is unrefined, extra virgin cold-pressed avocado oil?". Aocs.org. The American Oil Chemists’ Society. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Brazil nut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Katragadda, H. R.; Fullana, A. S.; Sidhu, S.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A. (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry. 120: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- "Canola oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Coconut oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Corn oil, industrial and retail, all purpose salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Wolke, Robert L. (May 16, 2007). "Where There's Smoke, There's a Fryer". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- "Cottonseed oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Linseed/Flaxseed oil, cold pressed, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Garavaglia J, Markoski MM, Oliveira A, Marcadenti A (2016). "Grape Seed Oil Compounds: Biological and Chemical Actions for Health". Nutr Metab Insights. 9: 59–64. doi:10.4137/NMI.S32910. PMC 4988453. PMID 27559299.

- Callaway, J.; Schwab, U.; Harvima, I.; Halonen, P.; Mykkänen, O.; Hyvönen, P.; Järvinen, T. (2005). "Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis". Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 16 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1080/09546630510035832. PMID 16019622.

- "Smoke points of oils" (PDF).

- "Olive oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Palm oil, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Vegetable Oils in Food Technology (2011), p. 61.

- "Safflower oil, salad or cooking, high oleic, primary commerce, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Soybean oil". FoodData Central. fdc.nal.usda.gov.

- "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, (partially hydrogenated), fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Soybean oil, salad or cooking, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Sunflower oil, 65% linoleic, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Sunflower oil, less than 60% of total fats as linoleic acid, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Sunflower oil, high oleic - 70% or more as oleic acid, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Smoke Point of Oils". Baseline of Health. Jonbarron.org. 2012-04-17. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- "Cottonseed oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Palm oil, industrial, fully hydrogenated, filling fat, fat composition, 100 g". US National Nutrient Database, Release 28, United States Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Leah Goldberg (2008-10-26). "Measuring Rate Capability of a Bakelite-Trigger RPC Coated with Linseed Oil". APS Division of Nuclear Physics Meeting Abstracts: DA.033. Bibcode:2008APS..DNP.DA033G.

- Poth, Ulrich (2001). "Drying Oils and Related Products". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_055. ISBN 3527306730.

- Merrifield, Mary P. (2012). Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting: Original Texts. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0486142241.

- George Franks (1999). Classic Wood Finishing (2nd ed.). Sterling. p. 96. ISBN 978-0806970639.

- "Caring for your Bat". Gunn & Moore.

- Ettling, Bruce V.; Adams, Mark F. (1971). "Spontaneous combustion of linseed oil in sawdust". Fire Technology. 7 (3): 225. doi:10.1007/BF02590415.

- Routley, J. Gordon; Jennings, Charles; Chubb, Mark (February 1991), "Highrise Office Building Fire One Meridian Plaza Philadelphia, Pennsylvania" (PDF), Report USFA-TR-049, Federal Emergency Management Agency

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Linseed oil. |