Lighthouse Chapel International

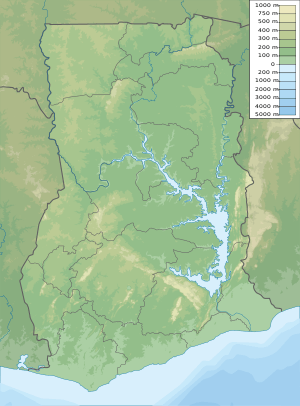

Lighthouse Chapel International (LCI) is a PentecostalChristian church founded in 1987 by Dag Heward-Mills and headquartered in Accra, Ghana. It is considered to be one of the leading charismatic churches in Ghana, and has over 3000 branches in many other countries in Africa, Europe, Asia, the Caribbean, Australia, the Middle East and the Americans.

| Lighthouse Chapel International | |

|---|---|

| |

| Theology | Pentecostal |

| Language | Multilingual |

| Headquarters | Qodesh, Accra, Ghana |

| Founder | Dag Heward-Mills |

| Origin | 1987 |

| Members | 38 756 |

| Official website | lighthousechapel.org |

History

It seemed like a lonely journey devoid of success, when Bishop Dag Heward-Mills began ministering the Christian Gospel in Accra, Ghana. This vision seems to continue unabated. This vision has birthed Lighthouse Chapel International and many other ministries. When he gained admission into the University of Ghana Medical School in October 1982, Dag as he was known as at the time, began a branch of Calvary Road Incorporated (CRI).

London and Victory Church

However events took a different turn when the government of the day closed down Universities for ten months. Towards the end of 1982, Dag left the country for England and worked under the Leadership of Pastor Michael Bassett in Victory Church. The burning desire to share the gospel was very much alive in his heart and so he channelled all his energies into music and the follow up ministry of the church where he met Robert Dodoo who became deputy head Usher of Victory Church. The two carried on in their various roles in church while maturing in Christian fellowship with each other as they constantly shared their ever-burning desire to share their experience of salvation with all who would listen.[1]

Korle-Bu Branch Beginnings

When the Universities re-opened in March 1984 Dag returned to Ghana and a resumption of CRI meetings. On 22 October of the same year Eddy a first year student turned up at one of the meetings and decided to join CRI. A relationship which was fuelled by a love for God and for humanity began to form among the three ‘Brothers’ who continued working assiduously to share the gospel, in addition to studying.

In spite of a desire to resign from CRI while still at Legon, Dag stayed on and still carried on with his duties at CRI. As he counselled and interacted with members of both sexes he decided on a relationship with Adelaide Baiden on August 26, 1985. At the time he was on a community health rotation at the Medical School.

In September of the same Year Dag was transferred to Korle-Bu with the rest of the MB III class of the Medical School. This signalled the beginning of yet another group who met to pray at the Korle-Gonno beach from 10PM TO 12AM every night. Unfortunately, the nightly prayer meetings were brought to an abrupt end when the group was attacked by drug addicts on the beach.

Undeterred, the meetings continued on the Indadfa Park but this was also terminated because of an attack by some armed men. Then started the Dawn Broadcasts or simply put, preaching at dawn. Even though E.A.T. Sackey preached his heart out, it was immediately met with hostile opposition and an unpleasant reaction from the Medical students.

In the midst of this hostility, in 1986, Dawn Broadcasts were also started at the NTC's House 10 where a lot of souls were won to Christ that dawn. These precious saints became the first members of CRI Korle-Bu branch. Finally heeding to the leading of the Holy Spirit to leave CRI and to begin a church, Dag made his assistant at Legon, the leader of CRI Korle-Bu. This was also in preparation for his imminent departure from CRI.

The Korle-Bu branch soon began to meet for Sunday Services at the Korle-Bu Christian Centre and E.A.T. Sackey preached at the first service at the Medical School Auditorium. Subsequent services however, were held at the school of Hygiene Lecture Room. This arrangement was short-lived because the Head of Anatomy Department refused to allow the fellowship to continue meeting at the auditorium. Even though the climate seemed discouraging and the prospects daunting, the fellowship continued to meet at the School of Hygiene Lecture Room on Sunday mornings and Tuesday evenings as well as having all-nights in the open forecourt of the Medical School Auditorium. As expected the church came under attack and persecution from Medical Students who claimed that their worship was a nuisance to them. Following on, a delegation of Medical Students met with the Dean of the Medical School, Professor Akyeampong requesting that the church be closed down or relocated.

The Dean contacted the Principal of the School of Hygiene on this matter and even though the outcome was in favour of the church as they had the Principal's full support, the CRI Headquarters objected to the holding of Sunday services, indicating that their vision was not to start a church at this time. Dag then resigned from CRI and a few weeks later his assistant who was in charge of the CRI Korle-Bu branch also resigned, leaving the fellowship without a leader.

Foundation

Soon after, Dag informed E.A.T. Sackey of his intention to start a church. E.A.T. Sackey was in full support of the decision but anxious about its viability and potential success so he suggested that the church begun in Nsawam, a small town not far from the capital Accra. However, Dag decided to stay his course.

In 1987, in the early hours of the New Year at Mensah Sarbah Hall, Legon, Dag decided to obey God and become a Pastor.[2] [3] He informed Asamoah and E.A.T. Sackey of this final decision to take up the role of pastoring the remnants of Korle-Bu Christian Centre (KCC). Following this decision, CRI Headquarters officially dissociated themselves from Dag and KCC. To drive home their point, the entire executive of CRI came to KCC; into the School of Hygiene Lecture Room on a Sunday morning and delivered a letter, officially ex-communicating Dag. The executive were not given the chance to address the congregation but their message and letter were received upstairs after the service. Dag announced to the fellowship that he was now their pastor much to the dissatisfaction of some of the leadership who therefore became disloyal to his cause. In the same month, Pastor Dag decided to change the name of KCC to ‘The Lighthouse’ because he believed that the vision of the Lighthouse extended beyond the suburb of Korle-Bu. More of the original group that formed KCC however became disenchanted with Pastor Dag's leadership and criticised him endlessly.

In September 1987, Eddy Addy who had completed his course at the University decided to attend ‘The Lighthouse’ regularly along with E.A.T. Sackey and Jake Godwyll.[4] They went on the church's first ever crusade at Agbozume. As events progressed, the main assistant of Pastor Dag came under immense pressure from certain pastors in the town to leave ‘The Lighthouse’. At the same time, another pastor who had once been a regular attendee to CRI meetings when Pastor Dag was leader, refused an invitation to preach at ‘The Lighthouse’ claiming that he did not ‘sow among thorns’.

The church expanded even amidst intense disloyalty and members spilled onto the upstairs corridor of the School of Hygiene. Pastor Dag decided to make changes to the leadership of the ever-growing church and in December 1987, during a meeting at the Medical Students Hostel. E.A.T. Sackey became Pastor Dag's assistant and the leader of Tuesday services.

So began the new year of 1988 with a new team of leaders assisting Pastor Dag. In April ‘The Lighthouse’ moved to the School of Hygiene Lecture Theatre downstairs with its 100 members and soon had to move upstairs because membership doubled. Subsequently, KCC became officially known as The Lighthouse Chapel and so began its vision of being a lighthouse to the lost.

In the middle of building a church and winning souls for Christ, Pastor Dag completed his medical studies on 10 March 1989 and qualified as a Medical Doctor.[4] A month later, on April 1, he started work as a House Officer based at the Paediatric Surgical department and then followed this milestone with the blessing of his marriage to Adelaide Baiden on June 8, 1989. Pastor E.A.T. Sackey had the immense pleasure and honour of officiating the ceremony between Pastor and Mrs Dag Heward-Mills at 4pm, at the Trinity College, Accra Ghana.

Medical School Canteen

Prior to this, LCI had moved to the Medical School Canteen for Sunday services while week day services were held at the Basic Sciences Department. Here many successes were celebrated including the church's first wedding between Mr and Mrs Bernard Brocke.

In July of the same year, the church moved its offices to N46 at the House Officers' flats. That same year in September, Pastor Eddy relocated to Akuse to take up a new position with the Volta River Authority.

Dag rendered an apology to the leaders of CRI for the error he committed towards them at the inception of The Lighthouse Chapel and restored the relationship.

Dag still combined work as a House Officer and lay Pastor. In 1990, he was ordained at the Victory Church, Finchley Road in London by Pastor Michael Basset. Due to church growth, with a 500 membership, LCI International started double services in the canteen. In the meantime Pastor Dag did odd jobs in Europe to raise finances that would enable him launch into full-time ministry and with additional financial support from his sister. Heward-Mills left medicine to become a full-time Pastor in 1991.[4]

The Korle Gonno Cathedral

The Church, in 1992 then renovated and converted an old cinema in the Korle Gonno area into a large cathedral seating over 3000 people. From there Dag began to teach on church planting and sent out many of his members as missionaries to start branches of the Lighthouse Chapel in other nations, towns and cities of the world. Korle Gonno Cathedral was considered as headquarters of LCI, from April 1993 to December 2005.[5] The building was renamed "Light of the World Cathedral" in 2010. In 2003 the main Chapel of the Qodesh drew about 3,000 worshipers to Sunday services.[4]

The Qodesh

In January 2006, "The Qodesh" became the headquarters of LCI, in the North Kaneshie suburb of Accra, Ghana.[6] The building has a seating capacity of 10000. Two chapels are named after bishops Addy and Sackey, and a third is named after Adelaide Heward-Mills, wife of the LCI leader and now first lady and reverend minister of Lighthouse Chapel. [7] The Adelaide chapel includes a beautiful Bell Tower.

In 2011, the Qodesh has an attendance of 2,500. [7] The Qodesh holds multiple services in various chapels on the complex on every day of the week. Services are conducted in Twi, French and English. There are also separate services for youth and children, as well as meetings devoted to prayer, water baptism and healing.

The Qodesh means "The Holy Hill" [lower-alpha 1] and is the largest megachurch Ghana. Led by other Bishops of LCI, from dawn to dusk and beyond there constant services and meetings. Throughout the three morning services, starting at 6.30AM and the early evening service at 4.00pm (for young people).

The Qodesh has hosted many renowned Christian Speakers such as Charles E. Blake, Benny Hinn, Archbishop Nicholas Duncan-Williams, Larry Stockstill, Richard Roberts and Mosa Sono.

In the World

In 2011, LCI claimed to have 687 churches in 79 countries, with 27,811 members in Ghana and 38,756 members worldwide.[7] [9]

Most of the members in Ghana are from urban areas, which LCI targeted first, but as of 2011 the church reported 46 rural missions in Ghana.[7]

LCI imposes strict rules and regulations on its overseas branches and requires them to follow the standard guidelines for key events such as marriages, funerals and outdooring ceremonies.[10] LCI is concerned about the risk that members of the overseas branches may become to permissive morally, and considers it has a mission to keep them on the "narrow path of salvation."[11] LCI considers that it has a mandate to evangelize the world. For example, as of 2014 there were a few hundred members in Switzerland with church services in eleven cities led by missionaries from Ghana.[12]

Humanitarian implication

The denomination maintains a humanitarian ministry to widows, prisoners, the blind and the poor in society as well as the sick.[13] It also founded an orphanage, the Lighthouse Christian Children's Home, to cater for orphans and a primary school, the Lighthouse Christian Mission School, to ensure their education.[14] There is also an hospital, The Lighthouse Mission Hospital & Fertility Center (LMHFC). These outfits are under the management of Heward-Mills' wife, Lady Rev. Adelaide Heward-Mills.

Activities

LCI began as a student evangelistic ministry. It has developed into a transnational church with members mainly from the professional classes but still draws its strength from student evangelism on the campus of the University of Ghana. The Campus Church branch owns buses and banners and organizes crusades.[15] Elders and shepherds are selected from born-again students in this branch, and the founder holds an annual meeting with the elders, shepherds, and members of the branch.[15] Ministers and missionaries are trained at the Anagkazo Bible and Ministry Training Center and the Christ Mission Academy.[16] LCI organizes youth camps which teach Christianity and also include leadership workshops.[17] LCI emphasizes church planting and lay leadership, with lower importance given to healing compared to other churches in the region.[18] Heward-Mills has written that to succeed a church must be run in a strict and hierarchical manner, with rebels quickly identified and ejected.[19]

LCI depends on tithes to cover expenses. As Dag Heward-Mills has written, "Prosperity in its most basic form consists of someone sowing a seed and later harvesting the returns. Not paying your tithes separates you from this most basic principle of sowing and reaping. When you do not pay your tithes you harm your finances because you take away the foundations of prosperity.[20] However, although Pentecostals often say that wealth is a sign of divine prosperity, the problem of extravagant lifestyles of Pentecostal leaders is recognized, and LCI has instituted a code of conduct for its pastors.[21] Heward-Mills wrote the LCI code of ethics, published as Ministerial Ethics: Practical Wisdom for Christian Ministers. In it he recognizes the social pressure felt by ministers.[22] In the case of misbehavior by a minister, such as embezzlement or sexual misconduct, LCI attempts to rehabilitate the offender. After complying with the sanction they are encouraged to resume or continue their ministry.[23]

The church evangelizes through Healing Jesus Crusades and Lighthouse Media. Heward-Mills delivers his message by preaching, through books, and through video and audio cassettes.[7] He describes "soaking" in taped messages as a way to allow the Spirit to enter the body.[24] Heward-Mills publishes the quarterly magazine A Healing Jesus and broadcasts The Mega Word.[16] In July 2009 Heward-Mills conducted a five-day crusade in Obuasi, a decaying gold-mining town, attended by over 280,000 people.[25] In June 2012 Heward-Mills consecrated three ministers of the church as bishops at the Qodesh, the headquarters of the church.[26] A service held on Good Friday in April 2015 in Independence Square, Accra included songs by a 5,000 member mass choir and a sermon by Bishop Dag Heward-Mills. With "tens of thousands" of attendees, the event may have been the largest ever to be held in the city.[27]

Paul Gifford has asserted that Lighthouse and other PCCs are "resolutely opposed" to socioeconomic development. However, according to Akyerefo, Lighthouse and Royalhouse Chapel International members are encouraged to become involved in Ghanaian public culture, and the church may support moves towards grE.A.T. Sackeyer gender equality.[28] Both Lighthouse and Royalhouse make significant efforts in health care, orphan care and education.[29] The LCI orphanage at Aburi in Ghana's Eastern Region was founded in 2006 and was soon caring for four boys and fifteen girls, with ages ranging from infants to eleven-year-olds. The administrator of the orphanage is resident pastor of the local Lighthouse branch. There are five caregivers, known as mothers, and a primary school.[30] In 2013 the orphanage received a donation from members of Action Chapel International, Adenta.[31]

LCI plays an active role when a couple indicates that they are considering marriage, with the pastor sometimes taking part in the negotiations between the families and making every effort to ensure that the "white" wedding is seen as the main ceremony.[32] LCI operates a basic school in Accra teaching to the junior secondary level, and in 2006 founded a 40-bed hospital at its Qodesh complex in Accra. The hospital in 2006 had four medical doctors, nine nurses and five paramedics, and included an X-ray department, eye clinic, laboratory, and pharmacy. Patients of all faiths were admitted and were expected to pay if they were able.[33] During the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in 2014 the church told its members to stop using handshakes and hugs when meeting.[34]

In contrast to other charismatic churches, LCI took a position in opposition to the government of Jerry Rawlings.[35] LCI has clashed with supporters of traditional religions. For example, on Sunday 31 May 1998, a group of traditionalists in the Korle Gonno district of Accra stormed the Lighthouse chapel in Korle Gonno, vandalizing the church and seriously injuring members of the congregation. The immediate cause of the conflict was the church's insistence on loud music during their services, which often lasted through the night, in refusal to recognize the traditional practice of "sacred silence".[36]

Mission

LCI's mission statement lists the following:

1. To build 25,000 churches

2. To have Churches in 150 countries

3. To fight fiercely and relentlessly in all battles for the advancement of the churches and the Gospel

4. To produce radical Christians who work for God

5. To go to heaven and to hear Jesus say - "Well done, good and faithful servant"

Beliefs

The Church is against prosperity theology. [37]

LCI is a member of the National Association of Charismatic and Christian Churches (NACCC)[38] and the Pentecostal World Fellowship. [39]

See also

References

- The Hebrew word qodesh means holy, hallowed or sanctified.[8]

- http://www.lighthousechapelswitzerland.org/ch1/features/history

- TaWo, Afrikaner missionieren das gottlose Europa, tageswoche.ch, Switzerland, October 23, 2014

- LCI, Our history Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, LCI's website, Ghana, retrieved June 22, 2016

- Gifford 2004, p. 25.

- LCI Korle Gonno, Light of the World Cathedral Archived 2016-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, LCI Korle Gonno's website, Ghana, retrieved June 22, 2016

- LCI Korle Gonno, Light of the World Cathedral Archived 2016-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, LCI Korle Gonno's website, Ghana, retrieved June 22, 2016

- Englund 2011, p. 208.

- Englund 2011, p. 215.

- LCI, Worldwide Missions Archived 2016-06-28 at the Wayback Machine, LCI's website, Ghana, retrieved June 22, 2016

- Rijk Van Dijk 2004, p. 458.

- Rijk Van Dijk 2004, p. 460.

- Samuel Schlaefli 2014.

- LCI, Help the helpless, Help the helpless's website, Ghana, retrieved June 22, 2016

- F.A.W. Cofie, Public Relations Practice in the Lighthouse Chapel International and the International Central Gospel Church Archived 2016-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, Doctorate thesis, University of Ghana, Ghana, 2013, page 61

- Englund 2011, p. 206.

- Englund 2011, p. 209.

- Englund 2011, p. 212.

- Sanneh & Carpenter 2005, p. 84.

- Yemisi Ogbe 2014.

- Thomas 2012, p. 139.

- Quampah 2014, p. xi.

- Quampah 2014, p. 144.

- Quampah 2014, p. 143.

- Marleen De Witte 2003, p. 196.

- Good leadership can restore … Obuasi.

- Rev. Fabin consecrated at Lighthouse Chapel International.

- The largest gathering in Accra? 2015.

- Cooper & Morrell 2014, p. 169–170.

- Englund 2011, p. 205.

- Englund 2011, p. 210.

- Obour K. Samuel 2013.

- Rijk Van Dijk 2004, p. 446.

- Englund 2011, p. 211.

- Lighthouse Chapel Bans Handshakes, Hugs.

- Anderson 2013, p. 238.

- Hoover & Kaneva 2009, p. 170–171.

- Samuel Nii Narku Dowuona, Prosperity preaching is 'nonsense' - Bishop Dag, modernghana.com, Ghana, April 6, 2015

- Quampah 2014, p. 4.

- Pentecostal World Fellowship, Membership, pentecostalworldfellowship.org, Malaysia, retrieved January 15, 2020

Sources

- Aboderin, Isabella (2011-12-31). Intergenerational Support and Old Age in Africa. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-0929-0. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adejunmobi, Moradewun (2004-01-01). Vernacular Palaver: Imaginations of the Local and Non-native Languages in West Africa. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-772-5. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adogame, Afeosemime Unuose; Echtler, Magnus; Vierke, Ulf (2008). Unpacking the New: Critical Perspectives on Cultural Syncretization in Africa and Beyond. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-0719-1. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Allan H. (2013-02-21). To the Ends of the Earth: Pentecostalism and the Transformation of World Christianity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538642-4. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burchardt, Marian (2015). Multiple Secularities Beyond the West: Religion and Modernity in the Global Age. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 1-61451-978-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Brenda; Morrell, Robert (2014-08-01). Africa-Centred Knowledges: Crossing Fields and Worlds. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84701-095-7. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Englund, Harri (2011-08-15). Christianity and Public Culture in Africa. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4366-8. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Ghana's Richest Pastors". Modern Ghana. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- Gifford, Paul (2004). Ghana's New Christianity: Pentecostalism in a Globalizing African Economy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21723-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Good leadership can restore the fortunes of Obuasi – Evangelist Heward-Mills". Ghana News Agency. GNA. 20 July 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Gornik, Mark R.; Walls, Andrew (2011-07-22). Word Made Global: Stories of African Christianity in New York City. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6448-2. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoover, Stewart M.; Kaneva, Nadia (2009-08-09). Fundamentalisms and the Media. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84706-133-1. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Lighthouse Chapel Bans Handshakes, Hugs". Peacefm online. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Marleen De Witte (May 2003). "Altar Media's "Living Word": Televised Charismatic Christianity in Ghana". Journal of Religion in Africa. BRILL. 33 (2, Religion and the Media). JSTOR 1581654.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Obour K. Samuel (28 October 2013). "Action Chapel donates to Lighthouse Orphanage". Graphic. Retrieved 16 April 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quampah, Dela (2014-08-20). Good Pastors, Bad Pastors: Pentecostal Ministerial Ethics in Ghana. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62564-051-2. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Rev. Fabin consecrated at Lighthouse Chapel International". Myjoyonline. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Rijk Van Dijk (November 2004). "Negotiating Marriage: Questions of Morality and Legitimacy in the Ghanaian Pentecostal Diaspora". Journal of Religion in Africa. BRILL. 34 (4, Uncivic Religion: African Religious Communities and Their Quest for Public Legitimacy in the Diaspora). JSTOR 1581507.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Jonathan (September 2009). "Prosperity Gospel in the Superchurches of Accra; Review of Paul Gifford, Ghana's New Christianity". H-Net Reviews, H-Africa. Retrieved 8 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Samuel Schlaefli (22 October 2014). "Es wird Zeit, dass wir die Schweiz retten". Die Tages Woche (in German). Retrieved 2015-05-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanneh, Lamin; Carpenter, Joel A. (2005-02-09). The Changing Face of Christianity: Africa, the West, and the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-029216-4. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schifrin, Tomas (21 February 2013). "What kind of light is Lighthouse Chapel International shining?". Modern Ghana. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The largest gathering in Accra?". Ghana web. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- Thomas, Pradip Ninan (2012-07-30). Global and Local Televangelism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-26481-7. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yemisi Ogbe (26 September 2014). "Nigeria's Superstar Men Of God". Citifmonline. Citi 97.3 FM. Retrieved 2015-05-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Nterful, Emmanuel Louis (2013). Church Expansion Through Church Planting in Ghana: A Case Study of the Lighthouse Chapel International Model. North-West University (South Africa). Potchefstroom Campus.

- Dag Heward-Mills (2008-06-04). Ministerial Ethics. Lux Verbi – BM. ISBN 978-0-7963-0808-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kweku Okyerefo, Michael Perry (2014). "African Churches in Europe. Transnational Dynamics in African Christianity: How Global Is The Lighthouse Chapel International Missionary Mandate?". Journal of African Religions. Penn State University Press. 2 (1): 95–124. JSTOR 10.5325/jafrireli.2.1.0095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)