Liberating Expedition of Peru

The Expedición Libertadora del Perú (English: Liberating Expedition of Peru) was a force organized in 1820 by Chilean government, with elements belonging to the Liberating Army of the Andes and to recently restored Army of Chile. On 5 February 1819, a treaty was signed between Chile and the United Provinces to finance and organize the expedition to Peru, but in fact, it is Chile who made the effort to do it, since the United Provinces are distracted by internal conflicts and the direct threat of invasion from Spain.[1] The expedition was the continuation of the plan of liberation that General José de San Martín conceived for the Spanish colonies in the Pacific of South America, with the support of General Bernardo O'Higgins in Chile. While the Chilean government headed by Bernardo O'Higgins played a pivotal role in organizing the expedition, the control of the Chilean Squadron was given to the British sailor Thomas Cochrane and the control of the Army was given to the Argentine General José de San Martín. The expedition liberated parts of Peru from Spanish Crown control. The complete liberation of Peru was achieved in 1824 with the intervention of Simón Bolívar.

| Liberating Expedition of Peru | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1820–1822 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Military forces |

| Role | Battle |

| Engagements | Spanish American wars of independence |

| Commanders | |

| Army Commander | José de San Martín |

| Fleet Commander | Thomas Cochrane |

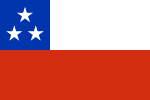

| Insignia | |

| The three stars related to the three nations involved: Chileans, United Provinces and Peruvians. |  |

Maitland Plan

According to Argentine historians like Felipe Pigna and Rodolfo Terragno, José de San Martín, was introduced to the plan during his stay in London in 1811 by members of the Logia Lautaro: a Freemasonic Lodge founded by Francisco de Miranda and Scottish Lord MacDuff (James Duff, 4th Earl Fife). San Martín was allegedly part of the lodge, and he took the Maitland Plan as a blueprint for the movements necessary to defeat the Spanish army in Chile and Peru; he carried on successfully with the last five points of the plan, and thus liberated the southern part of the continent.

Precedents

Between 1812 and 1814 the General Captaincy of Chile was reconquered by Fernando de Abascal, Viceroy of Perú, end in the Disaster of Rancagua, putting an end to the period named Patria Vieja (Old Homeland), in which the Chilean patriots had governed the destinations of the colony and conceived notable reforms to the colonial Spanish diet. After the above-mentioned event, the Chilean troops, along with the representatives of the government, fled to Mendoza, where they were received by the governor of the province of Cuyo General José de San Martín, the one who conceived in that moment a plan of liberation of the South American colonies of the Spanish Empire. This plan would consist of invading Chile with an army shaped by the remains of the Army of Chile, defeated in Rancagua, and Argentine troops. After the invasion and liberation of Chile, for the allied army, this one would embark by sea to Peru to extinguish the Spanish presence in that region, since it was considered a big threat for the independence of other Latin Americans countries.

The emancipation of Perú was to have been a common enterprise by Chile and Argentina.[2] Argentina, then a loose alliance of provinces, distracted by internal strife and another threat of invasion from Spain, was unable to contribute for the expedition and ordered José de San Martín back to Argentina. San Martín choose to disobey (see Acta de Rancagua) and O'Higgins decided that Chile would assume the costs of the Freedom Expedition of Perú.[1](p39)

The Squadron

On 20 August 1820 the expedition sailed from Valparaíso for Paracas, near Pisco in Perú. The escort was provided by the squadron and comprised the flagship O'Higgins (under Captain Thomas Sackville Crosbie), frigate San Martín (Captain William Wilkinson), frigate Lautaro (Captain Martin Guise), the corvette Independencia (Captain Robert Forster), the brigs Galvarino (Captain John Tooker Spry), Araucano (Captain Thomas Carter), and Pueyrredón (Lieutenant William Prunier) and the schooner Moctezuma (Lieutenant George Young).[3](p98)

Every expeditionary ship got a painted number so that it could be identified at a distance. There are discrepancies between authors about the names and number and some names of the transports.[4]

| Ship name | Ship number | tons | Other names | troops | personnel or cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potrillo[Notes 1] | 20 | 180 | 0 | 1400 boxes of munitions for infantry and artillery, 190 boxes munitions for flamethrowerfor and 8 barrels powder | |

| Consecuencia | 11 | 550 | Argentina | 561 | |

| Gaditana | 10 | 250 | 236 | 6 guns | |

| Emprendedora | 12 | 325 | Empresa | 319 | 1280 boxes musket balls, 1500 boxes supplies of tools and repair shop |

| Golondrina | 19 | 120 | 0 | 100 boxes munition, 190 boxes clothes, 460 sack kekse, 670 bunches jerked beef | |

| Peruana | 18 | 250 | 53 | hospital, physicians and 200 boxes | |

| Jerezana | 15 | 350 | 461 | ||

| Minerva | 8 | 325 | 630 | ||

| Águila[Notes 1] | 14 | 800 | not Brigantine Pueyrredón |

752 | 7 guns |

| Dolores[Notes 1] | 9 | 400 | 395 | ||

| Mackenna | ? | 500 | 0 | 960 boxes with weapons, armors and leather goods for infantry and cavalry. 180 quintal iron pieces | |

| Perla | 16 | 350 | 140 | 6 guns | |

| Santa Rosa | 13 | 240 | Santa Rosa de Chacabuco or Chacabuco |

372 | 6 guns |

| Nancy | 21 | 200 | 0 | 80 horses and fodder | |

- Property of Thomas Cochrane, hired out to Chile, Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, page 144

On 8 September 1820 the liberating army disembarked 100 miles southeast of Lima: of the 4118 soldiers, 4000 of them were Chileans.[5](p144)

On the night of 5 November, Cochrane personally and 240 volunteers wearing white with blue armbands captured the Spanish frigate Esmeralda within the port of Callao. She was renamed Valdivia and commissioned into the Chilean Navy.

References

- Simon Collier, William F. Sater, A history of Chile, 1808-1994, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-56075-6

- See English translation of the Treaty in Edmund Burke, The Annual register, or, A view of the history, politics, and literature for the Year 1819, page 138

- Brian Vale, Cochrane in the Pacific, I.B. Tauris & Co ltd, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-446-6

- We use here the list of Gerardo Etcheverry Principales naves de guerra a vela hispanoamericanas. Archived 2012-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 21. January 2011. The Hercules, Veloz and Zaragoza are not in the list.

- Carlos Lopez Urrutia, Historia de la Marina de Chile, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1969, url