Leodegar

Leodegar of Poitiers (Latin: Leodegarius; French: Léger; c. 615 – October 2, 679 AD) was a martyred Burgundian Bishop of Autun. He was the son of Saint Sigrada and the brother of Saint Warinus.

Saint Leodegar (or Leger) Bishop of Autun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 615 Autun, Saône-et-Loire, Burgundy, France |

| Died | October 2, 679 Sarcing, Somme, Picardie, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Cathedral of Autun and the Grand Séminaire of Soissons |

| Feast | October 2 |

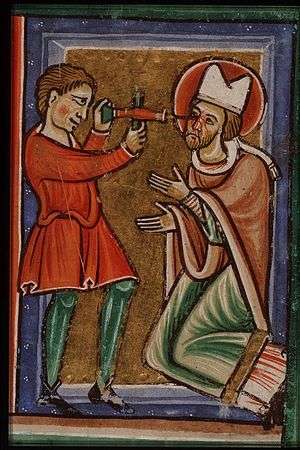

| Attributes | Man having his eyes bored out with a gimlet Bishop holding a gimlet Bishop holding a hook with two prongs |

| Patronage | Millers Invoked against blindness Eye disease Eye problems Sore eyes |

Leodegar was an opponent of Ebroin, the Frankish Mayor of the Palace of Neustria and the leader of the faction of Austrasian nobles in the struggle for hegemony over the waning Merovingian dynasty. His torture and death made him a martyr and saint.[1]

Early life

Leodegar was the son of a high-ranking Burgundian nobleman, Bodilon, Count of Poitiers and Paris and Sigrada of Alsace, who later became a nun at Sainte-Marie de Soissons. His brother was Warinus.[1]

He spent his childhood in Paris at the court of Clotaire II, King of the Franks and was educated at the palace school. When he was older he was sent to Poitiers, where there was a long-established cathedral school, to study under his maternal uncle, Desiderius (Dido), Bishop of Poitiers. At the age of 20 his uncle made him an archdeacon.[1]

Shortly afterwards he became a priest, and in 650, with the bishop's permission, became a monk at the monastery of St Maxentius in Poitou.[2] He was soon elected abbot, and initiated reforms including the introduction of the Benedictine rule.[1]

Career

Around 656, about the time of the usurpation of Grimoald in Austrasia and the banishment of the boy-heir Dagobert II, Leodegar was called to the Neustrian court by the widowed Queen Bathilde to assist in the government of the united kingdoms and in the education of her children. Then in 659 he was named to the see of Autun, in Burgundy. He again undertook the work of reform and held a council at Autun in 661. The council denounced Manichaeism and was the first to adopt the Trinitarian Athanasian Creed. He made reforms among the secular clergy and in the religious communities, and had three baptisteries erected in the city. The church of Saint-Nazaire was enlarged and embellished, and a refuge established for the indigent. Leodegar also caused the public buildings to be repaired and the old Roman walls of Autun to be restored.[3] His authority at Autun placed him as a leader among the Franco-Burgundian nobles.

Meanwhile, in 660 the Austrasian nobles demanded a king, and young prince Childeric II was sent to them through the influence of Ebroin, the mayor of the palace in Neustria. The queen withdrew, from a court that was Ebroin's in all but name, to an abbey she had founded at Chelles, near Paris. On the death of King Clotaire III in 673, a dynastic struggle ensued, with rival claimants as pawns; Ebroin raised Theoderic to the throne, but Leodegar and the other bishops supported the claims of his elder brother Childeric II, who, by the help of the Austrasians and Burgundians, was eventually made king. Ebroin was interned at Luxeuil and Theoderic sent to St. Denis.[3]

Leodegar remained at court, guiding the young king. In 673 or 675, however, Leodegar was also sent to Luxeuil. The cause, a protest against the marriage of Childeric and his first cousin, is a hagiographic convention;[4] as a leader of the Austrasian and Burgundian nobles, Leodegar was easily represented as a danger by his enemies. When Childeric II was murdered at Bondi in 673, by a disaffected Frank, Theoderic III was installed as king in Neustria, making Leudesius his mayor. Ebroin each took advantage of the chaos to make his escape from Luxeuil and hasten to the court. In a short time Ebroin caused Leudesius to be murdered and became mayor once again, still Leodegar's implacable enemy.[3]

About 675 the Duke of Champagne, the Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne and the Bishop of Valence, stirred up by Ebroin, attacked Autun, and Leodegar fell into their hands. At Ebroin's instigation, Leodegar's eyes were gouged out and the sockets cauterized, and his tongue was cut out. Some years later Ebroin persuaded the king that Childeric had been assassinated at the instigation of Leodegar. The bishop was seized again, and, after a mock trial, was degraded and condemned to further exile, at Fécamp, in Normandy. Near Sarcing he was led out into a forest on Ebroin's order and beheaded.[5]

A dubious[4] testament drawn up at the time of the council of Autun has been preserved as well as the Acts of the council. A letter which he caused to be sent to his mother after his mutilation is likewise extant.

In 782, his relics were translated from the site of his death, Sarcing in Artois, to the site of his earliest hagiography – the Abbey of St Maxentius (Saint-Maixent) near Poitiers. Later they were removed to Rennes and thence to Ebreuil, which place took the name of Saint-Léger in his honour. Some relics are still kept in the cathedral of Autun and the Grand Séminaire of Soissons. In 1458 Cardinal Rolin caused his feast day to be observed as a holy day of obligation.

For sources to his biography, there are two early (though not contemporaneous) Lives,[6] drawn from the same lost source (Krusch 1891), and also two later ones (one of them in verse).

Cultural significance

Historically there was a custom among wealthy British merchants to sell in May, spend the summer outside of London, then to return on St Leger's Day. This gave rise to the saying used in regards to financial trading markets, "Sell in May and go away, and come on back on St. Leger's Day".[7]

See also

- Liber Historiae Francorum

- List of Catholic saints

- Saint Leodegar, patron saint archive

Notes

- Butler, Rev. Alban. "The Lives of the Saints, Volume X: October". St. Leodegarius, or Leger, Bishop and Martyr. bartleby.com. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Now Saint-Maixent-l'École, in the région Poitou-Charentes

- MacErlean, Andrew. "St. Leodegar." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 23 October 2017

- Adriaan Breukelaar (1992). "Leodegar". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 4. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 1466–1468. ISBN 3-88309-038-7.

- Weninger, Francis Xavier. "St. Leodegar, Bishop and Martyr", Lives of the Saints, Vol. 2, P. O'Shea, 1876

- Passio Leudegarii I & II. The second one is much more embellished than the first.

- "Sell In May And Go Away". Investopedia. InterActiveCorp. 4 July 2012.

![]()

Sources

Primary sources

- Liber Historiae Francorum, edited by B. Krusch, in MGH SS rer. Merov. vol. ii.

- Passio Leudegarii I & II, edited by B. Krusch and W. Levison, in MGH SS rer. Merov. vol v.

- Vita sancti Leodegarii, by Ursinus, then a monk of St Maixent (Migne, Patrilogia Latina, vol. xcvi.)

- Vita metrica in Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, vol. iii. (Mod. Germ. Hist.)

- Epistolae aevi Merovingici collectae 17, edited by W. Gundlach, in MGH EE vol iii.

Secondary sources

- Adriaan Breukelaar (1992). "Leodegar". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 4. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 1466–1468. ISBN 3-88309-038-7.

- J. Friedrich, Zur Geschichte des Hausmeiers Ebroin, in the Proceedings of the Academy of Munich (1887, pp. 42–61)

- J. B. Pitra, Histoire de Saint Léger (Paris, 1846)