Lenny Bruce

Leonard Alfred Schneider (October 13, 1925 – August 3, 1966), better known by his stage name Lenny Bruce, was an American stand-up comedian, social critic, and satirist. He was renowned for his open, freestyle and critical form of comedy which contained satire, politics, religion, sex and vulgarity.[2] His 1964 conviction in an obscenity trial was followed by a posthumous pardon, the first in the history of New York state, by Governor George Pataki in 2003.[3]

Lenny Bruce | |

|---|---|

Bruce in 1961 | |

| Born | Leonard Alfred Schneider October 13, 1925 Mineola, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 3, 1966 (aged 40) Hollywood Hills, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Drug overdose |

| Resting place | Eden Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1947–1966 |

| Spouse(s) | [1] |

| Children | 1 |

| Comedy career | |

| Medium | Stand-up, television, books |

| Genres | Satire, political satire, black comedy, blue comedy |

| Subject(s) | American culture, American politics, race relations, religion, human sexuality, obscenity, pop culture |

| Notable works and roles | The Lenny Bruce Originals The Carnegie Hall Concert Let the Buyer Beware How to Talk Dirty and Influence People |

| Signature | |

Bruce is renowned for paving the way for outspoken counterculture era comedians. His trial for obscenity is seen as a landmark for freedom of speech in the United States.[4][5][6] In 2017, Rolling Stone magazine ranked him third (behind disciples Richard Pryor and George Carlin) on its list of the 50 best stand-up comics of all time.[7]

Early life

Lenny Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider to a Jewish family in Mineola, New York, grew up in nearby Bellmore, and attended Wellington C. Mepham High School.[8] Lenny's parents divorced before he turned ten, and he lived with various relatives over the next decade. His British-born father, Myron (Mickey) Schneider, was a shoe clerk, and the two saw each other very infrequently. Bruce's mother, Sally Marr (legal name Sadie Schneider, born Sadie Kitchenberg), was a stage performer and had an enormous influence on Bruce's career.[9]

After spending time working on a farm, Bruce joined the United States Navy at the age of 16 in 1942, and saw active duty during World War II aboard the USS Brooklyn (CL-40) fighting in Northern Africa; Palermo, Italy, in 1943; and Anzio, Italy, in 1944. In May 1945, after a comedic performance for his shipmates in which he was dressed in drag, his commanding officers became upset. He defiantly convinced his ship's medical officer that he was experiencing homosexual urges.[10] This led to his undesirable discharge in July 1945. However, he had not admitted to or been found guilty of any breach of naval regulations and successfully applied to have his discharge changed to "Under Honorable Conditions ... by reason of unsuitability for the naval service".[11] In 1959, while taping the first episode of Hugh Hefner's Playboy's Penthouse, Bruce talked about his Navy experience and showed a tattoo he received in Malta in 1942.[12]

After a short stint in California spent living with his father, Bruce settled in New York City, hoping to establish himself as a comedian. However, he found it difficult to differentiate himself from the thousands of other show-business hopefuls who populated the city. One locale where they congregated was Hanson's, the diner where Bruce first met the comedian Joe Ancis,[13] who had a profound influence on Bruce's approach to comedy. Many of Bruce's later routines reflected his meticulous schooling at the hands of Ancis.[14] According to Bruce's biographer Albert Goldman, Ancis's humor involved stream-of-consciousness sexual fantasies and references to jazz.[15]

Bruce took the stage as "Lenny Marsalle" one evening at the Victory Club, as a stand-in master of ceremonies for one of his mother's shows. His ad-libs earned him some laughs. Soon afterward, in 1947, just after changing his last name to Bruce, he earned $12 and a free spaghetti dinner for his first stand-up performance in Brooklyn.[16] He was later a guest—and was introduced by his mother, who called herself "Sally Bruce"—on the Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts radio program. Lenny did a bit inspired by Sid Caesar, "The Bavarian Mimic", featuring impressions of American movie stars (e.g., Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and Edward G. Robinson).[17]

Career

Bruce's early comedy career included writing the screenplays for Dance Hall Racket in 1953, which featured Bruce, his wife Honey Harlow, and mother Sally Marr in roles; Dream Follies in 1954, a low-budget burlesque romp; and a children's film, The Rocket Man, in 1954. In 1956, Frank Ray Perilli, a fellow nightclub comedian who eventually became a screenwriter of two dozen successful films and plays, became a mentor and part-time manager of Bruce.[18] Through Perilli, Bruce met and collaborated with photojournalist William Karl Thomas on three screenplays (Leather Jacket, Killer's Grave and The Degenerate), none of which made it to the screen, and the comedy material on his first three comedy albums.[19]

Bruce was a roommate of Buddy Hackett in the 1950s. The two appeared on the Patrice Munsel Show (1957–1958), calling their comedy duo the "Not Ready for Prime Time Players",[20] twenty years before the cast of Saturday Night Live used the same name. In 1957, Thomas booked Bruce into the Slate Brothers nightclub, where he was fired the first night for what Variety headlined as "blue material"; this led to the theme of Bruce's first solo album on Berkeley-based Fantasy Records, The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce,[21] for which Thomas shot the album cover. Thomas also shot other album covers, acted as cinematographer on abortive attempts to film their screenplays, and in 1989 authored a memoir of their ten-year collaboration titled Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet.[22] The 2016 biography of Frank Ray Perilli titled The Candy Butcher,[23] devotes a chapter to Perilli's ten-year collaboration with Bruce.

Bruce released a total of four albums of original material on Fantasy Records, with rants, comic routines, and satirical interviews on the themes that made him famous: jazz, moral philosophy, politics, patriotism, religion, law, race, abortion, drugs, the Ku Klux Klan, and Jewishness. These albums were later compiled and re-released as The Lenny Bruce Originals. Two later records were produced and sold by Bruce himself, including a 10-inch album of the 1961 San Francisco performances that started his legal troubles. Starting in the late 1950s, other unissued Bruce material was released by Alan Douglas, Frank Zappa and Phil Spector, as well as Fantasy. Bruce developed the complexity and tone of his material in Enrico Banducci's North Beach nightclub, the "hungry i", where Mort Sahl had earlier made a name for himself.

Branded a "sick comic", Bruce was essentially blacklisted from television, and when he did appear thanks to sympathetic fans like Hefner and Steve Allen, it was with great concessions to Broadcast Standards and Practices.[24] Jokes that might offend, like a bit on airplane glue-sniffing teenagers that was done live for The Steve Allen Show in 1959, had to be typed out and pre-approved by network officials. On his debut on Allen's show, Bruce made an unscripted comment on the recent marriage of Elizabeth Taylor to Eddie Fisher, wondering, "Will Elizabeth Taylor become bar mitzvahed?"[25]

On February 3, 1961, in the midst of a severe blizzard, Bruce gave a famous performance at Carnegie Hall in New York. It was recorded and later released as a three-disc set, titled The Carnegie Hall Concert. In the posthumous biography about Bruce, Albert Goldman described the night of the concert as follows:[26]

It's all a trip- and the best of it is you have the faintest idea where you're going! Lenny worshiped the gods of Spontaneity, Candor and Free Association. His greatest fear was getting his act down pat. On this night, he rose to every chance stimulus, every interruption and noise and distraction, with a mad volleying of mental images that suggested the fantastic riches of Charlie Parker's horn. The first flash was simply the spectacle of people pilled up in America's most famous concert hall.

On August 1965, a year before his death, he went on his final stand-up show, mainly talking about his legal troubles about profanity. The performance was believed to be lost, until it was found on a hard drive by YouTube user Max in 2018.[27]

Personal life

In 1951, Bruce met Honey Harlow, a stripper from Manila, Arkansas. They were married that same year, and Bruce was determined she would end her work as a stripper.[28] The couple eventually left New York in 1953 for the West Coast, where they got work as a double act at the Cup and Saucer in Los Angeles. Bruce then went on to join the bill at the club Strip City. Harlow found employment at the Colony Club, which was widely known to be the best burlesque club in Los Angeles at the time.[29]

Bruce left Strip City in late 1954 and found work within the San Fernando Valley at a variety of strip clubs. As the master of ceremonies, he introduced the strippers while performing his material. The clubs of the Valley provided the perfect environment for Bruce to create new routines: According to his primary biographer, Albert Goldman, it was "precisely at the moment when he sank to the bottom of the barrel and started working the places that were the lowest of the low" that he suddenly broke free of "all the restraints and inhibitions and disabilities that formerly had kept him just mediocre and began to blow with a spontaneous freedom and resourcefulness that resembled the style and inspiration of his new friends and admirers, the jazz musicians of the modernist school."[30]

Honey and Lenny's daughter Kitty Bruce was born in 1955.[31] Honey and Lenny had a tumultuous relationship. Many serious domestic incidents occurred between them, usually the result of serious drug use.[32] They broke up and reunited over and over again between 1956 and Lenny's death in 1966. They first separated in March 1956, and were back together again by July of that year when they travelled to Honolulu for a night club tour. During this trip, Honey was arrested for marijuana possession. Prevented from leaving the island due to her parole conditions, Lenny took the opportunity to leave her again, and this time kidnapped the then one-year-old Kitty.[33] In her autobiography, Honey claims Lenny turned her in to the police. She would be later sentenced to two years in federal prison.[34]

Throughout the final decade of his life, Bruce was beset by severe drug addiction. He would use heroin, meth and dilaudids daily. He suffered numerous health problems and personal strife as a result of his addiction.[35]

He had an affair with the jazz singer Annie Ross in the late 1950s.[36] In 1959, Lenny's divorce from Honey was finalized.

Legal troubles

Bruce's desire to help his wife cease working as a stripper led him to pursue schemes that were designed to make as much money as possible. The most notable was the Brother Mathias Foundation scam, which resulted in Bruce's arrest in Miami, Florida, in 1951 for impersonating a priest. He had been soliciting donations for a leper colony in British Guiana (now Guyana) under the auspices of the "Brother Mathias Foundation", which he had legally chartered—the name was his own invention, but possibly referred to the actual Brother Matthias who had befriended Babe Ruth at the Baltimore orphanage to which Ruth had been confined as a child.[37]

Bruce had stolen several priests' clergy shirts and a clerical collar while posing as a laundry man. He was found not guilty because of the legality of the New York state-chartered foundation, the actual existence of the Guiana leper colony, and the inability of the local clergy to expose him as an impostor. Later, in his semifictional autobiography How to Talk Dirty and Influence People, Bruce said that he had made about $8,000 in three weeks, sending $2,500 to the leper colony and keeping the rest.

Obscenity arrests

On October 4, 1961, Bruce was arrested for obscenity[38] at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco; he had used the word cocksucker and riffed that "to is a preposition, come is a verb", that the sexual context of come is so common that it bears no weight, and that if someone hearing it becomes upset, he "probably can't come".[39] Although the jury acquitted him, other law enforcement agencies began monitoring his appearances, resulting in frequent arrests under charges of obscenity.

Bruce was arrested again in 1961, in Philadelphia, for drug possession and again in Los Angeles, two years later. The Los Angeles arrest took place in then-unincorporated West Hollywood, and the arresting officer was a young deputy named Sherman Block, who later became County Sheriff. The specification this time was that the comedian had used the word schmuck, an insulting Yiddish term that is an obscene term for penis. The Hollywood charges were later dismissed.[40]

On December 5, 1962, Bruce was arrested on stage at the legendary Gate of Horn folk club in Chicago.[41] That same year, he played at Peter Cook's The Establishment club in London, and in April the next year he was barred from entering the United Kingdom by the Home Office as an "undesirable alien".[42]

In April 1964, he appeared twice at the Cafe Au Go Go in Greenwich Village, with undercover police detectives in the audience. He was arrested along with the club owners, Howard and Elly Solomon, who were arrested for allowing an obscene performance to take place. On both occasions, he was arrested after leaving the stage, the complaints again pertaining to his use of various obscenities.[43]

A three-judge panel presided over his widely publicized six-month trial, prosecuted by Manhattan Assistant D.A. Richard Kuh, with Ephraim London and Martin Garbus as the defense attorneys. Bruce and club owner Howard Solomon were both found guilty of obscenity on November 4, 1964. The conviction was announced despite positive testimony and petitions of support from—among other artists, writers and educators—Woody Allen, Bob Dylan, Jules Feiffer, Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, William Styron, and James Baldwin, and Manhattan journalist and television personality Dorothy Kilgallen and sociologist Herbert Gans.[44] Bruce was sentenced on December 21, 1964, to four months in a workhouse; he was set free on bail during the appeals process and died before the appeal was decided. Solomon later saw his conviction overturned.[45]

Later years

Despite his prominence as a comedian, Bruce appeared on network television only six times in his life.[46] In his later club performances, he was known for relating the details of his encounters with the police directly in his comedy routine. These performances often included rants about his court battles over obscenity charges, tirades against fascism, and complaints that he was being denied his right to freedom of speech. Bruce was banned outright from several U.S. cities.

In September 1962, his only visit to Australia caused a media storm—although, contrary to popular belief, he was not banned nor was he forced to leave the country. Bruce was booked for a two-week engagement at Aaron's Exchange Hotel, a small pub in central Sydney by the American-born, Australian-based promoter Lee Gordon, who was by then deeply in debt, nearing the end of his formerly successful career, and desperate to save his business. Bruce's first show at 9 p.m. on September 6 was uneventful, but his second show at 11 p.m. led to a major public controversy. Bruce was heckled by audience members during his performance, and when local actress Barbara Wyndon stood up and complained that Bruce was only talking about America, and asked him to talk about something different, a clearly annoyed Bruce responded, "Fuck you, madam. That's different, isn't it?" Bruce's remark shocked some members of the audience and several walked out.

By the next day the local press had blown the incident up into a major controversy, with several Sydney papers denouncing Bruce as "sick" and one even illustrating their story with a retouched photograph appearing to show Bruce giving a fascist salute. The venue owners immediately canceled the rest of Bruce's performances, and he retreated to his Kings Cross hotel room. Local university students (including future OZ magazine editor Richard Neville) who were fans of Bruce's humor tried to arrange a performance at the Roundhouse at the University of New South Wales, but at the last minute the university's Vice-Chancellor rescinded permission to use the venue, with no reason given [47] and an interview he was scheduled to give on Australian television was cancelled in advance by the Australian Broadcasting Commission.[48]

Bruce remained largely confined to his hotel, but eight days later gave his third and last Australian concert at the Wintergarden Theatre in Sydney's eastern suburbs. Although the theatre had a capacity of 2,100, only 200 people attended, including a strong police presence, and Bruce gave what was described as a "subdued" performance. It was long rumored that a tape recording of Bruce's historic performance was made by police, but it was, in fact, recorded by local jazz saxophonist Sid Powell, who brought a portable tape recorder to the show. The tape was rediscovered in 2011 in the possession of Australian singer Sammy Gaha, who had acted as Bruce's chauffeur during his visit, and it was subsequently donated to the Lenny Bruce audio collection at Brandeis University. Bruce left the country a few days later and spoke little about the experience afterwards.[49][50][51][52]

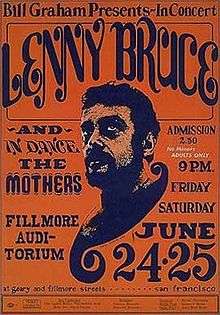

Increasing drug use also affected Bruce's health. By 1966, he had been blacklisted by nearly every nightclub in the U.S., as owners feared prosecution for obscenity. He gave a famous performance at the Berkeley Community Theatre in December 1965, which was recorded and became his last live album, titled The Berkeley Concert; his performance here has been described as lucid, clear and calm, and one of his best. His last performance took place on June 25, 1966, at The Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, on a bill with Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention.[53] The performance was not remembered fondly by Bill Graham, whose memoir describes Bruce as "whacked out on amphetamine;" [54] Graham thought that Bruce finished his set emotionally disturbed. Zappa asked Bruce to sign his draft card, but the suspicious Bruce refused.[55]

At the request of Hefner and with the aid of Paul Krassner, Bruce wrote an autobiography. Serialized in Playboy in 1964 and 1965, this material was later published as the book How to Talk Dirty and Influence People.[56] During this time, Bruce also contributed a number of articles to Krassner's satirical magazine The Realist.[57]

Death and posthumous pardon

On August 3, 1966, a bearded Bruce was found dead in the bathroom of his Hollywood Hills home at 8825 W. Hollywood Blvd.[5] The official photo, taken at the scene, showed Bruce lying naked on the floor, a syringe and burned bottle cap nearby, along with various other narcotics paraphernalia. Record producer Phil Spector, a friend of Bruce, bought the negatives of the photographs "to keep them from the press." The official cause of death was "acute morphine poisoning caused by an overdose." [58]

Bruce's remains were interred in Eden Memorial Park Cemetery in Mission Hills, California, but an unconventional memorial on August 21 was controversial enough to keep his name in the spotlight. Over 500 people came to the service to pay their respects, led by Spector. Cemetery officials had tried to block the ceremony after advertisements for the event encouraged attendees to bring box lunches and noisemakers. Dick Schaap eulogized Bruce in Playboy, with the last line: "One last four-letter word for Lenny: Dead. At forty. That's obscene".

His epitaph reads: "Beloved father – devoted son / Peace at last."

Bruce had one daughter.[59][60] At the time of his death, his girlfriend was comedian Lotus Weinstock.[61]

On December 23, 2003, thirty-seven years after Bruce's death, New York Governor George Pataki granted him a posthumous pardon for his obscenity conviction.[62][63]

Legacy

—syndicated columnist Sydney J. Harris, November 5, 1969.[64]

Bruce was the subject of the 1974 biographical film Lenny, directed by Bob Fosse and starring Dustin Hoffman (in an Academy Award-nominated Best Actor role), and based on the Broadway stage play of the same name written by Julian Barry and starring Cliff Gorman in his 1972 Tony Award-winning role. In addition, the main character's editing of a fictionalized film version of Lenny was a major part of Fosse's own autobiopic, the 1979 Academy Award-nominated All That Jazz; Gorman again played the role of the stand-up comic.

The documentary Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth, directed by Robert B. Weide and narrated by Robert De Niro, was released in 1998. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature

In 2004, Comedy Central listed Bruce at number three on its list of the 100 greatest stand-ups of all time, placing above Woody Allen (4th) and below Richard Pryor (1st) and George Carlin (2nd).[65] Both comedians who ranked higher than Bruce considered him a major influence; Pryor said that hearing Bruce for the first time "changed my life,"[66] while Carlin was arrested along with Bruce after refusing to provide identification when police raided a Bruce performance.[67]

In popular culture

- In 1966, Grace Slick co-wrote and sang the Great Society song "Father Bruce."[68]

- Bruce is pictured in the top row of the cover of the Beatles 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[69]

- The clip of a news broadcast featured in "7 O'Clock News/Silent Night" by Simon & Garfunkel carries the ostensible newscast audio of Lenny Bruce's death. In another track on the album Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, "A Simple Desultory Philippic (or How I Was Robert McNamara'd into Submission)," Paul Simon sings, "... I learned the truth from Lenny Bruce, that all my wealth won't buy me health."[70]

- Tim Hardin's fourth album Tim Hardin 3 Live in Concert, released in 1968, includes his song Lenny's Tune written about his friend Lenny Bruce.[71]

- Nico's 1967 album Chelsea Girl includes a track entitled "Eulogy to Lenny Bruce," which was "Lenny's Tune" by Tim Hardin, with the lyrics slightly altered. In it she describes her sorrow and anger at Bruce's death.[72]

- Bob Dylan's 1981 song "Lenny Bruce" from his Shot of Love album describes a brief taxi ride shared by the two men. In the last line of the song, Dylan recalls: "Lenny Bruce was bad, he was the brother that you never had."[73] Dylan has included this song live in concert as recently as November 2019.[74]

- Phil Ochs wrote a song eulogizing the late comedian, titled "Doesn't Lenny Live Here Anymore?" The song is featured on his 1969 album Rehearsals for Retirement.[75]

- Australian group Paul Kelly And The Dots' 1982 album Manila features a track named "Lenny (To Live Is to Burn)", which includes a couple clips of Lenny Bruce performing.

- R.E.M.'s 1987 song "It's the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)" includes references to a quartet of famous people all sharing the initials L.B. with Lenny Bruce being one of them (the others being Leonard Bernstein, Leonid Brezhnev and Lester Bangs). The opening line of the song mentioning Bruce goes, "... That's great, it starts with an earthquake, birds and snakes, an aeroplane, and Lenny Bruce is not afraid."[76]

- The 1990 cult comedy-drama film Pump Up the Volume starring Christian Slater, featured Lenny Bruce's autobiography entitled: "How to Talk Dirty and Influence People" as the contributing factor behind the vulgarity of the protagonist pirate radio DJ character 'Happy Harry Hard-On', that Slater portrayed.

- "La Vie Boheme," a song from the 1994 Broadway musical RENT, mentions Lenny Bruce in its lyrics. The characters hold a toast to bohemianism and shout out what and who inspires them. "Ginsberg, Dylan, Cunningham, and Cage, Lenny Bruce, Langston Hughes...to the stage!"

- In the 1996 remake "Nutty Professor", Eddie Murphy says to comedian Dave Chappelle, "You the next Lenny Bruce." (Nutty Professor 1996)

- Lenny Bruce appears as a character in Don DeLillo's 1997 novel Underworld. In the novel, Bruce does a stand-up routine about the Cuban Missile Crisis.[77]

- Genesis' 1974 song "Broadway Melody of 1974" depicts a dystopic New York where "Lenny Bruce declares a truce and plays his other hand, Marshall McLuhan, casual viewin', head buried in the sand" and "Groucho, with his movies trailing, stands alone with his punchline failing."[78]

- Joy Zipper's 2005 album The Heartlight Set features a track named "For Lenny's Own Pleasure."[79]

- Nada Surf's song "Imaginary Friends" (from their 2005 album The Weight Is a Gift) references Lenny Bruce in its lyrics: "Lenny Bruce's bug eyes stare from an LP, asking me just what kind of fight I've got in me."[80]

- Shmaltz Brewing Company brews a year-round beer called Bittersweet Lenny's R.I.P.A. and the tagline is "Brewed with an obscene amount of hops."[81]

- A fictionalized version of the comedian is played by Luke Kirby as a recurring character in the Amazon series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, in which he is portrayed as a friend and champion of the titular character. Kirby won an Emmy for his portrayal in 2019.[82]

- Metric's song "On the Sly" (from their 2007 album Grow Up and Blow Away) references Lenny Bruce in its lyrics: "for Halloween I want to be Lenny Bruce"[83]

Bibliography

- Bruce, Lenny. Stamp Help Out! (Self-published pamphlet, 1962)

- Bruce, Lenny. How to Talk Dirty and Influence People (Playboy Publishing, 1967)

- Autobiography, released posthumously

By others:

- Barry, Julian. Lenny (play) (Grove Press, Inc. 1971)

- Bruce, Honey. Honey: The Life and Loves of Lenny's Shady Lady (Playboy Press, 1976, with Dana Benenson)

- Bruce, Kitty. The (almost) Unpublished Lenny Bruce (1984, Running Press) (includes a graphically spruced up reproduction of 'Stamp Help Out!')

- Cohen, John, ed., compiler. The Essential Lenny Bruce (Ballantine Books, 1967)

- Collins, Ronald and David Skover, The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall & Rise of an American Icon (Sourcebooks, 2002)[84]

- DeLillo, Don. Underworld, (Simon and Schuster Inc., 1997)

- Denton, Bradley. The Calvin Coolidge Home for Dead Comedians, an award-winning collection of science fiction stories in which the title story has Lenny Bruce as one of the two protagonists.

- Goldman, Albert, with Lawrence Schiller. Ladies and Gentlemen – Lenny Bruce!! (Random House, 1974)

- Goldstein, Jonathan. Lenny Bruce Is Dead (Coach House Press, 2001)

- Josepher, Brian. What the Psychic Saw (Sterlinghouse Publisher, 2005)

- Kofsky, Frank. Lenny Bruce: The Comedian as Social Critic & Secular Moralist (Monad Press, 1974)

- Kringas, Damian. Lenny Bruce: 13 Days In Sydney (Independence Jones Guerilla Press, Sydney, 2010) A study of Bruce's ill-fated September 1962 tour down under.

- Marciniak, Vwadek P., Politics, Humor and the Counterculture: Laughter in the Age of Decay (New York etc., Peter Lang, 2008).

- Marmo, Ronnie, with Jason M. Burns. I'm Not a Comedian, I'm Lenny Bruce (Play directed by Joe Mantegna, 2017)

- Smith, Valerie Kohler. Lenny (novelization based on the Barry-scripted/Fosse-directed film) (Grove Press, Inc., 1974)

- Thomas, William Karl. Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet [85] Memoir and pictures from Bruce's principal collaborator. First printing, Archon Books, 1989; second printing, Media Maestro, 2002; Japanese edition, DHC Corp. Tokyo, 2001.

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Walking My Baby Back Home | Writer | Uncredited |

| Dance Hall Racket | Vincent | Directed by Phil Tucker | |

| 1954 | Dream Follies | ||

| The Rocket Man | Screenplay | Directed by Oscar Rudolph | |

| 1955 | The Leather Jacket | Actor / writer | 20 minutes of a feature film project that lost funding and was never completed |

| 1959 | One Night Stand: The World of Lenny Bruce | Himself / writer | TV special |

| 1967 | The Lenny Bruce Performance Film | Himself / writer | Filmed in San Francisco 1966, includes Thank You Mask Man, VHS 1992 / DVD 2005 / download |

| 1971 | Thank You Mask Man | Voice of 'The Lone Ranger' / writer / director | Animated short film by John Magnuson Associates |

| Dynamite Chicken | Himself | Sketch comedy film starring Richard Pryor | |

| 1972 | Lenny Bruce Without Tears | Himself | Documentary directed by Fred Baker, VHS 1992 / DVD 2005 / download 2013 |

| 1974 | Lenny | Biography directed by Bob Fosse and starring Dustin Hoffman as Lenny | Hoffman was nominated for:

|

| 1984 | A Toast to Lenny Bruce | Himself | TV tribute available on LaserDisc / VHS |

| 1998 | Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth | Himself | Academy award nominated documentary directed by Robert B. Weide, narrated by Robert De Niro |

| 2011 | Looking for Lenny | Himself | Documentary featuring interviews with Mort Sahl, Phyllis Diller, Lewis Black, Richard Lewis, Sandra Bernhard, Jonathan Winters, Robert Klein, Shelley Berman and others, North American Premiere Toronto Jewish Film Festival May 2011, screened at Paris Beat Generation Days April 2011 |

Discography

Albums

| Year | Title | Label | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Interviews of Our Times | Fantasy Records | LP / LP 1969 / CD 1991 / download | 2 tracks feature Henry Jacobs & Woody Leifer, liner notes by Horace Sprott III & Sleepy John Estes |

| 1959 | The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce | LP / LP / 8-track 1984 / CD 1991, 2012 & 2017 / download 2010 | Liner notes by Ralph J. Gleason | |

| 1960 | I Am Not a Nut, Elect Me! (Togetherness) | LP / CD 1991 / download | ||

| 1961 | American | LP / CD 1991, 2013 & 2016 / download | ||

| 1964 | Lenny Bruce Is Out Again | Lenny Bruce | LP / download 2004 | Self-published live recordings from 1958–1963 |

| 1966 | Lenny Bruce Is Out Again | Philles Records | Totally different version PHLP-4010, produced by Phil Spector |

Posthumous releases

| Year | Title | Label | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Why Did Lenny Bruce Die? | Capitol Records | LP / LP 1974 / download 2014 | Interviews and recordings by Lawrence Schiller, Lionel Olay and Richard Warren Lewis |

| 1967 | Lenny Bruce | United Artists Records | LP / LP 1986 | Recorded February 4, 1961, edited, reissued as In Concert At Carnegie Hall |

| 1968 | The Essential Lenny Bruce Politics | Douglas Records | LP / download 2007 | Clips edited together with archival audio for historical context |

| 1969 | The Berkeley Concert | Bizarre Records/Reprise Records | 2×LP / 2×LP 1971 / cassette 1991 / CD 1989, 2004 & 2017 / download 2005 | Recorded December 12, 1965, produced by John Judnich and Frank Zappa |

| 1970 | To Is A Preposition; Come Is A Verb | Douglas Records | LP / LP 1971, 1975 & 2004 / CD 2000 & 2002 / download 2005 & 2007 | Recorded 1961–1964, LP reissues titled What I Was Arrested For |

| 1971 | Live at the Curran Theater | Fantasy Records | 3×LP / 2×CD 1999 & 2017 / download 2006 | Recorded November 19, 1961 |

| 1972 | Carnegie Hall | United Artists Records | 3×LP / 2×CD 1995 / download 2015 | Recorded February 4, 1961, unabridged |

| 1974 | The Law, Language And Lenny Bruce | Warner-Spector Records | LP / cassette | Produced by Phil Spector |

| 1992 | Lenny Bruce | Rhino Entertainment | CD / CD 2005 | Soundtrack From "The Lenny Bruce Performance Film" and reissued as Live in San Francisco 1966 |

| 1995 | Live 1962: Busted! | Viper's Nest Records | CD / download 2010 & 2018 | Recorded December 4, 1962 at Chicago Gate of Horn, reissued as Dirty Words – Live 1962 & The Man That Shocked Britain: Gate of Horn, Chicago, December 1962 |

| 2004 | Let the Buyer Beware | Shout! Factory | 6×CD / book | Previously unreleased material, produced by Hal Willner |

Compilations

| Year | Title | Label | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | The Best Of Lenny Bruce | Fantasy Records | LP / cassette 1990 / LP 1995 | |

| 1972 | Thank You Masked Man | LP / CD 2004 & 2005 | Enhanced CD with Thank You Masked Man short film | |

| 1975 | The Real Lenny Bruce | 2×LP | Gatefold with inserts and poster | |

| 1982 | Unexpurgated : The Best Of Lenny Bruce | LP | ||

| 1991 | The Lenny Bruce Originals Volume 1 | CD / CD 1992 & 1997 / download 2006 / CD 2013 | Reissue of first and second albums | |

| The Lenny Bruce Originals Volume 2 | Reissue of third and fourth albums | |||

| 2011 | Classic Album Collection | Golden Stars | 3×CD 2012 | First 4 albums with 4 bonus tracks |

| 2013 | Great Audio Moments, Vol. 33: Lenny Bruce | Global Journey | download | 22 tracks, 105 minutes |

| Great Audio Moments, Vol. 33: Lenny Bruce Pt. 1 | 9 tracks, 39 minutes | |||

| Great Audio Moments, Vol. 33: Lenny Bruce Pt. 2 | 9 tracks, 43 minutes | |||

| 2016 | Four Classic Albums Plus Bonus Tracks | Real Gone Music | 4×CD | First 4 albums with bonus tracks |

Audiobooks

| Year | Title | Label | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Shut Your Mouth And Open Your Mind – The Rise & Reckless Fall of Lenny Bruce | Chrome Dreams | CD / CD 2001 & 2005 / CD / download 2006 / CD 2017 | Biography read by Robin Clifford, stand up by Lenny and voices of people who knew him. |

| 2002 | The Trials of Lenny Bruce | Sourcebooks MediaFusion | CD / book | Features excerpts of Lenny's never-before-released trial tapes |

| 2016 | Lenny Bruce: How to Talk Dirty and Influence People: An Autobiography | Hachette Audio | download / CD 2017 | Read by Ronnie Marmo, Preface by Lewis Black & Foreword by Howard Reich |

Tribute albums

| Year | Title | Label | Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Jarl Kulle: Som Lenny Bruce – Varför Gömmer Du Dig I Häcken? | Polar Music | 2×LP | Swedish actor performing Lenny, title translates to Like Lenny Bruce – Why are you hiding in the hedge? |

See also

- List of civil rights leaders

- Dirtymouth, a 1970 biographical film about Bruce

Footnotes

- August, Melissa (September 5, 2005). "Died". Time. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

78, ex-stripper who in 1951 married the soon-to-be-famous comedian Lenny Bruce; in Honolulu. Though the pair split in 1957 (they had a daughter, Kitty), the sometime actress who called herself "Lenny's Shady Lady" helped successfully lobby New York Governor George Pataki to pardon Bruce

- "Let There Be Laughter – Jewish Humor Around the World". Beit Hatutsot.

- Kifner, John (December 24, 2003). "No Joke! 37 Years After Death Lenny Bruce Receives Pardon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- Kifner, John (December 24, 2003). "No Joke! 37 Years After Death Lenny Bruce Receives Pardon". Nytimes.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- AP (August 4, 1966). "Obituary". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2001. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- Watkins, Mel; Weber, Bruce (June 24, 2008). "George Carlin, Comic Who Chafed at Society and Its Constraints, Dies at 71". The New York Times.

- The 50 Best Stand-up Comics of All Time. Rollingstone.com, retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Albert Goldman; Lawrence Schiller (1991). Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!!. Penguin Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-0140133622. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- Thomas, William Karl (December 1, 1989). Lenny Bruce: the making of a prophet. Archon Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-0208022370. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- A.H. Goldman. Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!! (New York: Random House, 1971), p. 91.

- "Lenny Bruce's Gay Naval Ruse: Unearthed documents detail comedian's discharge", TheSmokingGun.com, August 31, 2010

- ""Playboy's Penthouse" Episode #1.1 (TV Episode 1959)". Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Driven, Joey. "Joe Ancis: A Brief Biography". Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Goldman, p. 109.

- Goldman, pp. 105–108.

- "Lenny Bruce". Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Schwartz, Ben. "The Comedy Behind the Tragedy". Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- The Candy Butcher (2016) p. 152.

- Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet (1989) pp. 54–63.

- "Episode 966: Sandy Hackett". WTF with Marc Maron. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet (1989) pp. 276–229.

- Thomas, meta tags by William Karl Thomas; web design by William Karl. "Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet". www.mediamaestro.net. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- "The Candy Butcher (2016)". Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- "The Museum of Television & Radio Presents Two Five-Letter Words: Lenny Bruce". The Paley Center for Media. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Lenny Bruce on YouTube

- Goldman, Albert (1974). "Ladies and gentlemen - Lenny Bruce!!". archive.org. p. 349.

- "Lenny Bruce - Complete Live Standup (Rare, 1965)".

- Kottler, Jeffrey A., Divine Madness: Ten Stories of Creative Struggle (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006), 221.

- Goldman, p. 124.

- Goldman, p. 133.

- "Chronology – The 50s". The Official Lenny Bruce Site. Mystic Liquid. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- A.H. Goldman. Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!! (New York: Random House, 1971), p. 190.

- A.H. Goldman. Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!! (New York: Random House, 1971), p. 206.

- H. Bruce, D. Benenson. Honey: The Life and Loves of Lenny's Shady Lady (Mayflower, 1977)

- A.H. Goldman. Ladies and Gentlemen: Lenny Bruce!! (New York: Random House, 1971), p. 343.

- Gavin, James (October 3, 1993). "A Free-Spirited Survivor Lands on Her Feet". The New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- "Babe Ruth and Brother Matthias". Chatterfromthedugout.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "Lenny Bruce – Chronology". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Bruce, Lenny. "To is a Preposition, Come is a Verb". The Trials of Lenny Bruce. University of Missouri – Kansas City. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Gross, David C. English-Yiddish, Yiddish-English Dictionary: Romanized Hippocrene Books, 1995. p. 144. ISBN 0-7818-0439-6

- "Comedians in Courthouses Getting Cuffed: Lenny Bruce and George Carlin, December 1962". The Critic's Comic. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- "Chronology – The 60's | The Official Lenny Bruce Website". Lennybruceofficial.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Linder, Doug. "The Trials of Lenny Bruce". Famous Trials: The Lenny Bruce Trial 1964. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Excerpts from the Lenny Bruce Trial (Cafe Au Go Go) Archived June 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- People v. Solomon, 26 N.Y.2d. 621.

- "The Museum of Television & Radio Presents Two Five-Letter Words: Lenny Bruce". The Paley Center for Media. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Richard Neville (1995). Hippie Hippie Shake. Australia: William Heinemann. pp. 21–22. ISBN 0855615230.

- Goldman, p. 372.

- Derek Strahan. "When I opened for Lenny Bruce in Australia" (PDF). revolve.com. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- "Lenny Bruce's visit to Sydney 1962". dictionaryofsydney.org. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Michael Adams. "When Lenny Met Sydney" (PDF). michaeladamswrites wordpress site. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- "Lenny Bruce and his ill-fated Sydney tour". April 18, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Graham, Bill; Greenfield, Robert (2004). Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out. Da Capo Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0306813498. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- Graham, p. 159.

- Zappa, Frank; Occhiogrosso, Peter (1989). The Real Frank Zappa Book. Simon and Schuster. p. 69. ISBN 978-0671705725.

- Watts, Steven (2009). Mr Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American dream. John Wiley & Sons. p. 190. ISBN 978-0470501375.

- "The Realist Archive Project". Issues 15, 41, 48, 54.

- Collins, Ronald; Skover, David (2002). The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall and Rise of an American Icon. Sourcebooks Mediafusion. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-57071-986-8.

- Fox, Margalit (September 20, 2005). "Honey Bruce Friedman, 78, Entertainer and 'Lenny's Shady Lady'". New York Times. p. A27. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- O'Malley, Ryan. "Lenny Bruce's daughter reaching out: Pittston resident Kitty Bruce hopes to help women in recovery with "Lenny's House"". Pittston Dispatch. Pittston, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- Weide, Bob. "A Lotus by Any other Name", Whyaduck Productions, 1998, n.d.

- Minnis, Glenn "Lenny Bruce Pardoned", CBS News/Associated Press, December 23, 2003.

- Conan, Neal (December 23, 2003). "Lenny Bruce Pardoned: Interview with Nat Hentoff (with audio link)". Talk of the Nation. National Public Radio. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Harris, Sydney J. Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 5, 1969, p. 36.

- "List of Comedy Central's 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of All Time". listology.com. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- "Pryor: I Owe It All To Lenny Bruce". Contactmusic.com. May 21, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "Profanity". Penn & Teller: Bullshit!. Season 2. Episode 10. August 12, 2004. Showtime.

- "Grace Slick - Original Lyrics to her 1965 Lenny Bruce Tribute, "Father Bruce" (Recorded by the Great Society, her Pre-Jefferson Airplane Group)".

- Roger Griffiths (January 6, 2006). "Who Are They?". Math.mercyhurst.edu. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Bruce Eder. "allmusic album review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Richie Unterberger (April 10, 1968). "Tim Hardin Live 3 in Concert allmusic album review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "sputnikmusic album review". Sputnikmusic.com. April 27, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Paul Nelson (October 15, 1981). "Rolling Stone review". Rollingstone.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "New York, New York". November 24, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- "HuffPost is now a part of Verizon Media".

- Ventre, Michael (October 29, 2005). "Turn up the volume and cast your vote: Songs to inspire you for Election Day 2004". Retrieved September 1, 2006.. MSNBC. Archived from the original on November 4, 2004. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- "DeLillo in London".

- Holm-Hudson, Kevin (July 5, 2017). Genesis and the Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. ISBN 978-1351565806.

- "Joy Zipper – For Lenny's Own Pleasure". Song Meanings. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- "Nada Surf – Imaginary Friends".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 31, 2009. Retrieved July 19, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "71st Emmy Awards Nominees and Winners". emmys.com. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- "Metric – on the Sly".

- "Seattle University". Classes.seattleu.edu. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet". Mediamaestro.net. June 3, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

References

- Test, George A (1977). "On 'Lenny Bruce without Tears'". College English. 38 (5): 517–519. doi:10.2307/376395. JSTOR 376395.

- "Lenny Bruce: Britannica Concise". Retrieved March 27, 2006.

- "Bruce, Lenny – The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05". Retrieved March 27, 2006.

- "Lenny Bruce: A Who2 Profile". Retrieved March 27, 2006.

- "A Genesis Discography". Retrieved September 14, 2012.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lenny Bruce |

- The Official Lenny Bruce Website

- FBI Records: The Vault – Lenny Bruce at fbi.gov

- Lenny Bruce on IMDb

- Lenny Bruce at Find a Grave

- Correspondence and Other Papers Pertaining to Lenny Bruce's Drug Case, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Articles

- "Famous Trials: The Lenny Bruce Trial, 1964", University of Missouri – Kansas City School of Law. Includes Linder, Douglas, "The Lenny Bruce Trial: An Account", 2003. WebCitation archive.

- Azlant, Edward. "Lenny Bruce Again", Shecky Magazine, August 22, 2006

- Gilmore, John. "Lenny Bruce and the Bunny", excerpt from Laid Bare: A Memoir of Wrecked Lives and the Hollywood Death Trip (Amok Books, 1997). ISBN 978-1-878923-08-0

- Harnisch, Larry. "Voices", Los Angeles Times, April 13, 2007. (Reminiscences by saxophonist Dave Pell)

- Kaufman, Anthony. "Robert Weide's 'Lenny Bruce': 12 Years in-the-Negotiations" at the Wayback Machine (archived April 16, 2008) (interview with Swear to Tell the Truth producer), Indiewire.com, April 16, 2008

- Hentoff, Nat. "Lenny Bruce: The crucifixion of a true believer", Gadfly March/April 2001

- Sloan, Will. "Is Lenny Bruce Still Funny?", Hazlitt, November 4, 2014

- Smith, Daniel V. "The Complete Lenny Bruce Chronology" (fan site)

- "Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet" Memoir and pictures from Bruce's principal collaborator, Media Maestro 2001.

- Kringas, Damian (2012). "Lenny Bruce's visit to Sydney 1962". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved October 2, 2015. [CC-By-SA]

Audio/video

- Works by Lenny Bruce at Faded Page (Canada)

- "Come and Gone/Thank you, Mr. Masked Man!", My KPFA – A Historical Footnote (1961 Jazz Workshop performance and two 1963 performances) at the Wayback Machine (archived April 16, 2008)

- Video Clips Relating to the Trial of Lenny Bruce as assembled by the University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School