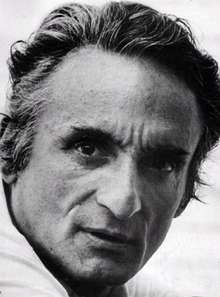

Larry Rivers

Larry Rivers (born Yitzroch Loiza Grossberg, August 17, 1923 – August 14, 2002) was an American artist, musician, filmmaker and occasional actor. Rivers resided and maintained studios in New York City, Southampton, Long Island, and Zihuatanejo, Mexico.

Larry Rivers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Yitzroch Loiza Grossberg August 17, 1923 Bronx, New York |

| Died | August 14, 2002 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Hans Hofmann School |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

| Movement | East Coast figurative painting, new realism, pop art |

| Spouse(s) | Augusta Berger (m. 1945–?; divorced) Clarice Price (m. 1961–1967; legally stayed together ) |

Early life

Larry Rivers was born in the Bronx to Samuel and Sonya Grossberg, Jewish immigrants from Ukraine.[1][2] From 1940–1945 he worked as a jazz saxophonist in New York City, changing his name to Larry Rivers in 1940 after being introduced as "Larry Rivers and the Mudcats" at a local pub. He studied at the Juilliard School of Music in 1945–46, along with Miles Davis, with whom he remained friends until Davis's death in 1991.

Training and career

Rivers is considered by many scholars to be the "Godfather" and "Grandfather" of Pop art, because he was one of the first artists to really merge non-objective, non-narrative art with narrative and objective abstraction.

Rivers took up painting in 1945 and studied at the Hans Hofmann School from 1947–48.[1] He earned a BA in art education from New York University in 1951.[1] He was a pop artist of the New York School, reproducing everyday objects of American popular culture as art. He was one of eleven New York artists featured in the opening exhibition at the Terrain Gallery in 1955. During the early 1960s Rivers lived in the Hotel Chelsea, notable for its artistic residents such as Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Leonard Cohen, Arthur C. Clarke, Dylan Thomas, Sid Vicious and multiple people associated with Andy Warhol's Factory and where he brought several of his French nouveau réalistes friends like Yves Klein who wrote there in April 1961 his Manifeste de l'hôtel Chelsea, Arman, Martial Raysse, Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Christo, Daniel Spoerri or Alain Jacquet, several of whom left, like him, some pieces of art in the lobby of the hotel : for payment of their rooms. In 1965 Rivers had his first comprehensive retrospective in five important American museums.

His final work for the exhibition was The History of the Russian Revolution, which was later on extended permanent display at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC. During 1967 he was in London collaborating with the American painter Howard Kanovitz. In 1968, Rivers traveled to Africa for a second time with Pierre Dominique Gaisseau to finish their documentary Africa and I, which was a part of the groundbreaking NBC series Experiments in Television. During this trip they narrowly escaped execution as suspected mercenaries.

During the 1970s Rivers worked closely with Diana Molinari and Michel Auder on many video tape projects, including the infamous Tits, and also worked in neon.[3]

Rivers's legs appeared in John Lennon and Yoko Ono's 1971 film Up Your Legs Forever.[4]

Personal life

Rivers married Augusta Berger in 1945, and they had one son, Steven.[2] Rivers also adopted Berger's son from a previous relationship, Joseph, and reared both children after the couple divorced.[2] He married Clarice Price in 1961, a Welsh school teacher who cared for his two sons.[5] Rivers and Clarice Price had two daughters, Gwynne and Emma. After six years, they separated.

Shortly after, he lived and collaborated with Diana Molinari, who featured in many of his works of the 1970s. After that Rivers lived with Sheila Lanham, a Baltimore artist and poet. In the early 1980s, Rivers and East Village figurative painter Daria Deshuk lived together and in 1985 they had a son, Sam Deshuk Rivers (now Sam D. Rivers). At the time of his death in 2002, poet Jeni Olin was his companion. Rivers also maintained a relationship with poet Frank O'Hara in the late 1950s and delivered the eulogy at O'Hara's funeral in 1966.

Paintings

Washington Crossing the Delaware is a 1953 painting by Rivers. Made of charcoal, oil paint, and linen, it is painted on linen and is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[6] In 1958 it was damaged by fire.[7]

Legacy

His primary gallery being the Marlborough Gallery in New York City. In 2002 a major retrospective of Rivers' work was held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. New York University bought correspondences and other documents from the Larry Rivers Foundation to house in their archive.[8] However, his daughters Gwynne and Emma objected to one particular film being displayed, as it depicts them naked as young children. The film's purpose is supposedly to be a documentation on their growth through puberty, but it was made without their consent. The matter was addressed in the December 2010 issue of the magazine Vanity Fair, and the October 2010 issue of Grazia. The film will never be publicly displayed as requested by both children.

See also

References

- "Biography". Larry Rivers Foundation. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Kimmelman, Michael (August 16, 2002). "Larry Rivers, Artist With an Edge, Dies at 78". New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- J.D. Reed (June 10, 1985). "The Canvas is the Night: Once a Visual Vagrant, Neon Has a Stylish New Glow". Time magazine.

Neon is the strongest, most direct form of illustration," argued Artist Larry Rivers in Rudi Stern's 1979 book Let There Be Neon. "And the canvas is the night.

- Jonathan Cott (16 July 2013). Days That I'll Remember: Spending Time With John Lennon & Yoko Ono. Omnibus Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-78323-048-8.

- McNay, Michael (August 17, 2002). "Larry Rivers: Rabelaisian American painter whose impressionistic and witty work predated pop art". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "Larry Rivers: Washington Crossing the Delaware". moma.org.

- "Permanent Revolution". New York magazine. September 10, 2012.

- Taylor, Kate (July 7, 2010). "Artist's Daughter Wants Videos Back". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

Further reading

- Baskind, Samantha, Jewish Artists and the Bible in Twentieth-Century America,Philadelphia, PA, Penn State University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-271-05983-9

- Marika Herskovic, New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 0-9677994-0-6. p. 8; p. 32; p. 38; p. 310–313