Lakhori bricks

Lakhori bricks or Badshahi bricks or Kakaiya bricks, are flat thin red colored burnt clay bricks, originating from the Indian subcontinent, that became increasingly popular element of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan; and remained so till early 20th century when lakhori bricks and similar Nanak Shahi bricks were replaced by the larger standard 9"x4"x3" bricks called ghumma bricks introduced by the colonial British India.[1][2][3][4]

Several still surviving famous 17th to 19th century structures of Mughal India, characterized by jharokhas, jalis, fluted sandstone columns, ornamental gateways and grand cusped-arch entrances are made of lakhori bricks, including fort palaces (such as Red Fort), protective bastions and pavilions (as seen in Bawana Zail Fortess), havelis (such as Bagore-ki-Haveli, Chunnamal Haveli, Ghalib ki Haveli, Dharampura Haveli and Hemu's Haveli), temples and gurudwaras (such as in Maharaja Patiala's Bahadurgarh Fort), mosques and tombs (such as Mehram Serai), water wells and baoli stepwells (such as Choro Ki Baoli), bridges (such as Mughal bridge at Karnal), Kos minar road-side milestones (such as at Palwal along Grand Trunk Road) and other structures.[5][6][7][8][9]

Origin

The exact origin of lakhori bricks is not confirmed, especially if they existed, or not, prior to becoming more prevalent in use during the Mughal India. Prior to the rise in frequent use of lakhori bricks during Mughal India, Indian architecture primarily used trabeated prop and lintel (point and slot) gravity-based technique of shaping large stones to fit into each other that required no mortar.[1] The reason lakhori bricks became more popular during the Mughal period, starting from Shah Jahan's reign, is mainly because lakhori bricks that were used to construct structures with the typical elements of Mughal architecture such as arches, jalis, jharokas, mouldings, cornices, cladding, etc. were easy to create intricate patterns due to the small shape and slim size of lakhori bricks.[10]

Regional, socio-strata and dimensional variations

The slim and compact Lakhorie bricks became popular across pan-Indian subcontinental Mughal Empire, specially in North India,[1] resulting in several variations in their dimensions as well as due to the use of lower strength local soil by poor people and higher strength clay by affluent people. Restoration architect author Anil Laul reasons that poor people used local soil to bake slimmer bricks using locally available cheaper dung cakes as fuel and richer people used higher-end thicker and bigger bricks made of higher strength clay baked in kilns using not so easily locally available more expensive coal, both methods yielded bricks of similar strength but different proportions at different economic levels of strata.[11]

“The lower the caste, the slimmer and smaller the brick, the higher the caste, the bigger the brick. It was not that they practiced or propagated the caste system. All that needs to be understood is that a poor person could use the local soil to burn slimmer and better bricks, using lesser fuel, to get a home that would withstand the vagaries of the elements and resist erosion and corrosion alike. In doing so, he could use even cow dung cakes as fuel for burning which would give him the desired brick. The rationale was obvious. The slimmer the brick- the lesser energy required to bake it. The higher caste could afford blending of clays and superior forms of fuel and transport produce over distances."

— Restoration architect author Anil Laul, Green is Red, Urban red herrings: excerpts from the "Green is Red"[11]

Lakhori bricks versus Nanak Shahi bricks

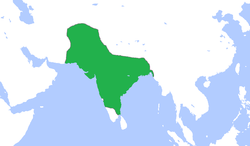

Mughal Empire at its largest spread during the late 17th to early 18th centuries; where lakhori bricks became popular since Shah Jahan's reign.

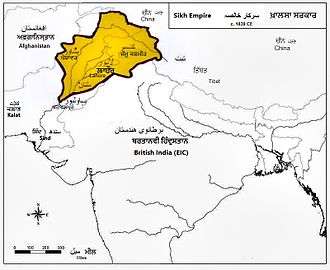

Mughal Empire at its largest spread during the late 17th to early 18th centuries; where lakhori bricks became popular since Shah Jahan's reign. Sikh Empire at its largest spread in the north-west Indian subcontinent during 1839 CE; where usage of Nanak Shahi bricks became more popular.

Sikh Empire at its largest spread in the north-west Indian subcontinent during 1839 CE; where usage of Nanak Shahi bricks became more popular.

Due to the lack of understanding, sometimes contemporary writers confuse the lakhori bricks with other similar but distinct regional variants. For example, some writers use "Lakhori bricks and Nanak Shahi bricks" implying two different things, and others use "Lakhori bricks or Nanak Shahi bricks" inadvertently implying either same or two different things, leading to confusion as if they are same, especially if these words are casually mentioned interchangeably.

Lakhori bricks were used by Mughal Empire that spanned across the Indian subcontinent,[1] whereas Nanak Shahi bricks were used mainly across the Sikh Empire,[12] that was spread across Punjab region in north-west Indian subcontinent,[13] when Sikhs were in conflict with Mughal Empire due to the religious persecution of Sikhs by Mughal Muslims.[14][15][16] Coins struck by Sikh rulers between 1764 CE to 1777 CE were called "Govind Shahi" coins (bearing inscription in the name of Guru Govind Singh), and coins struck from 1777 onward were called "Nanak Shahi" coins (bearing inscription in the name of Guru Nanak).[17][18]

A similar concept applies to the Nanak Shahi bricks of Sikh Empire, i.e. Lakhori and Nanak Shahi bricks being two similar, but a different type of bricks due to the regional variations as well as political reasons. Closely related similar things may be considered separate, and on the other hand considerably different things might be considered the same, in both cases due to the social-political-religious contextual reasons, for example closely related mutually intelligible Sanskritised-Hindustani language Hindi versus Arabised-Hindustani language Urdu being favored as separate languages by Hindus and Muslims respectively as seen in the context of Hindu-Muslim conflict that resulted in Partition of India, whereas mutually unintelligible speech varieties that differ considerably in structure such as Moroccan Arabic, Yemeni Arabic and Lebanese Arabic are considered the same language due to the pan-Islamism religious movement.[19][20][21]

Mughal-era lakhorie bricks predate the Nanak Shahi bricks as seen in Bahadurgarh Fort of Patiala that was built by Mughal Nawab Saif Khan in 1658 CE using earlier-era lakhori bricks, and nearly 80 years later it was renovated using later-era Nanak Shahi bricks and renamed in the honor of Guru Teg Bahadur (where Guru Teg Bahadur stayed at this fort for three months and nine days before leaving for Delhi when he was executed by Aurangzeb in 1675 CE) by Maharaja of Patiala Karam Singh in 1837 CE.[12][22][23][24] Since the timeline of both Mughal Empire and Sikh Empire overlapped, both Lakhori bricks and Nanak Shahi bricks were used around the same time in their respective dominions. Restoration architect author Anil Laul clarifies "We, therefore, had slim bricks known as the Lakhori and Nanakshahi bricks in India and the slim Roman bricks or their equivalents for many other parts of the world."[11]

Mortar recipe

They were used to construct structures with crushed bricks and lime mortar, and walls were usually plastered with lime mortar.[1] The concrete mixture of that era was a preparation of lime, surki (trass), jaggery and bael fruit (wood apple) pulp where some recipe used as much as 23 ingredients including urad ki daal (paste of vigna mungo pulse).[25]

References

- The Architectures of Shahjahanabad.

- "6. Wall gate and golf club.", Lodhi garden and golf club.

- Top 5 features of Lucknow architecture that make it unique..

- Feisal Alkazi, 2014, Srinagar: An Architectural Legacy

- "Haveli to speak of a history lost in time.", Times of India, 21 Dec 2015.

- 5. Havelis of Kucha pati Ram, in South Shahjahanabad, World Monument fund.

- Revival of Hemu's Haveli on the cards, Yahoo News India, 6 Aug 2015.

- A Zail, school and orphanage: Bawana's fortress gets another makeover.", Hindustan Times.

- Seeking brides, family restores old haveli Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, Times of India in INTACH newsletter, 21 Oct 2014.

- Madhulika Liddle, 2015, Crimson City

- Anil Laul, Urban Red Herrings - an extract from the book "Green in Red", 20 Aug 2015.

- Patiala's Mughal era fort to get Rs 4.3cr facelift, Times of India, 1 Jan 2015.

- "Ranjit Singh: A Secular Sikh Sovereign by K.S. Duggal. ''(Date:1989. ISBN 8170172446'')". Exoticindiaart.com. 3 September 2015. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- Markovits 2004, p. 98

- Melton, J. Gordon (Jan 15, 2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1163. Retrieved Nov 3, 2014.

- Jestice 2004, pp. 345–346

- Charles J. Rodgers, 1894, "Coin Collection in Northern India".

- Sun, Sohan Lal, 1885-89, "Umdat-ut-Twarikh", Lahore.

- Yaron Matras, 2010, Romani in Britain: The Afterlife of a Language: The Afterlife of a Language, Edinburgh University Press, p.5]

- Julie Tetel Andresen, Phillip M. Carter, Languages in the world: how history culture and politics shape language, p.7-8]

- Jacob Benesty, M. Mohan Sondhi and Yiteng Huang, 2008, separate language versus dialect and Springer handbook of speech processing, Springer Science+Business Media, p.798-.

- H.R. Gupta. History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. 1. ISBN 9788121502764.

- Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech (2014). The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 236–445, Quote:"this second martyrdom helped to make 'human rights and freedom of conscience' central to its identity." Quote:"This is the reputed place where several Kashmiri Pandits came seeking protection from Auranzeb's army.". ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Chandra, Satish. "Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom". The Hindu. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Bawana’s 19th-century fortress gets a makeover.", Hindustan Times, 20 Feb 2017.

External links

- Lakhori brick rampart of Bavana Fortress of Zail (administrative unit) of Jat chiefs[1]

- Haveli Dharampura built with lakhori bricks has a restaurant named "lakhori"