Léo Major

Léo Major DCM & Bar (January 23, 1921 – October 12, 2008) was a Canadian soldier who was the only Canadian and one of only three soldiers in the British Commonwealth to ever receive the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) twice in separate wars.[1] Major earned his first DCM in World War II in 1945 when he single-handedly liberated the city of Zwolle from German army occupation. He was sent to scout the city with one of his best friends, but he regarded Zwolle as too beautiful for a full-scale attack, deciding instead to clear it out himself. A firefight broke out in which his friend was killed, and after that, he put the commanders of each group of enemy soldiers he found at gunpoint until he could take the unit prisoner back at base. He repeated this until the entire city was clear of Nazi soldiers.[2] He received his second DCM during the Korean War for leading the capture of a key hill in 1951.

Léo Major | |

|---|---|

Major on 1 January 1944 | |

| Born | January 23, 1921 |

| Died | October 12, 2008 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Organization | Canadian Army |

| Children | Denis Major, Jocelyn Major, Daniel-aimé Major, Hélène Major |

Life

Born on January 23, 1921, New Bedford, Massachusetts, to French-Canadian parents, Léo Major moved with his family to Montreal before his first birthday. Due to a poor relationship with his father, he moved to live with an aunt at age 14. This relationship combined with a lack of available work led Major to join the Canadian army in 1940 to prove to his father that he was "somebody to be proud of".

World War II

Major was serving with the Régiment de la Chaudière that landed on the beaches in the Normandy Invasion on June 6, 1944.[3] During a reconnaissance mission on D-Day, Major captured a German armoured vehicle (a Hanomag) by himself. The vehicle contained German communication equipment and secret codes.[4] Days later, during his first encounter with an SS patrol, he killed four soldiers; however, one of them managed to ignite a phosphorus grenade. After the resulting explosion, Major lost one eye but he continued to fight. He continued his service as a scout and a sniper by insisting that he needed only one eye to sight his weapon. According to him, he "looked like a pirate".[5]

Major single-handedly captured 93 German soldiers during the Battle of the Scheldt in Zeeland in southern Netherlands.[6] During a reconnaissance, while alone, he spotted two German soldiers walking along a dike. As it was raining and cold, Major said to himself, "I am frozen and wet because of you so you will pay."[5] He captured the first German and attempted to use him as bait so he could capture the other. The second attempted to use his gun, but Major quickly killed him. He went on to capture their commanding officer and forced him to surrender. The German garrison surrendered themselves after three more were shot dead by Major. In a nearby village, SS troops who witnessed German soldiers being escorted by a Canadian soldier shot at their own soldiers, killing seven and injuring a few. Major disregarded the enemy fire and kept escorting his prisoners to the Canadian front line. Major then ordered a passing Canadian tank to fire on the SS troops. He marched back to camp with nearly a hundred prisoners. Thus, he was chosen to receive a Distinguished Conduct Medal. He declined the invitation to be decorated, however, because according to him General Montgomery (who was to give the award) was "incompetent" and in no position to be giving out medals.[5]

In February 1945, Major was helping a military chaplain load corpses from a destroyed Tiger tank into a Bren Carrier. After they finished, the chaplain and the driver seated themselves in the front whilst Major jumped in the back of the vehicle. The carrier struck a land mine. Major claims to have remembered a loud blast, followed by his body being thrown into the air and smashing down hard on his back. He lost consciousness and awoke to find two concerned medical officers trying to assess his condition. He simply asked if the chaplain was okay. They did not answer his question, but proceeded to load him onto a truck so he could be transported to a field hospital 30 miles (48 km) away, stopping every 15 minutes to inject morphine to relieve the pain in his back.[7]

First Distinguished Conduct Medal

At the beginning of April, the Régiment de la Chaudière were approaching the city of Zwolle, which was shown to have strong German resistance. The commanding officer asked for two volunteers to scout the German force before the artillery began firing on the city. Private Major and his friend Corporal Willie Arseneault stepped forward to accept the task. To keep the city intact, the pair decided to try to capture Zwolle alone, though they were only supposed to ascertain the German numbers and try to contact the Dutch Resistance.

Around midnight on 13 April, Arseneault was killed by German fire after accidentally giving away the pair's position and charging the Germans, killing two in the process. 1 Enraged, Major killed two more of the Germans, but the rest of the group fled in a vehicle. He decided to continue his mission alone. He entered Zwolle near Sassenpoort and came upon a staff car. He ambushed and captured the German driver and then led him to a bar where an armed officer was taking a drink. After disarming the officer, he found that they could both speak French (the officer was from Alsace). Major told him that at 6:00 a.m. Canadian artillery would begin firing on the city, which would cause numerous casualties among both the German troops and the civilians. The officer seemed to understand the situation, so Major took a calculated risk and let the man go, hoping they would spread the news of their hopeless position instead of rallying the troops. As a sign of good faith, he gave the German his gun back. Major then proceeded to run throughout the city firing his sub-machine gun, throwing grenades and making so much noise that he fooled the Germans into thinking that the Canadian Army was storming the city in earnest. As he was doing this, he would attack and capture German troops. About 10 times during the night, he captured groups of 8 to 10 German soldiers, escorted them out of the city and handed them over to French-Canadian troops waiting in the vicinity. After transferring his prisoners, he would return to Zwolle to continue his assault. Four times during the night, he had to force his way into civilians' houses to rest. He eventually located the Gestapo HQ and set the building on fire. Later stumbling upon the SS HQ, he engaged in a quick but deadly fight with eight Nazi officers: four were killed, the others fled. He noticed that two of the SS men he had just killed were disguised as Resistance members. The Zwolle Resistance had been (or was going to be) infiltrated by the Nazis.

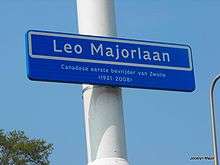

By 4:30 am, the exhausted Major found out that the Germans had retreated. Zwolle had been liberated,[8] and the Resistance contacted. Walking in the street, he met four members of the Dutch Resistance. He informed them that the city was now free of Germans. Major found out later that morning that the Germans had fled to the west of the River IJssel and, perhaps more importantly, that the planned shelling of the city would be called off and his Régiment de la Chaudière could enter the city unopposed. Major then took his dead friend back to the Van Gerner farm until regimental reinforcements could carry him away. He was back at camp by 9:00 am. For his actions, he received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

Second Distinguished Conduct Medal

When the war in Korea broke out, the Canadian government decided to raise a force to join the United Nations in repelling the communist invasion. Major was called back and ended up in the Scout and Sniper Platoon of 2nd Battalion Royal 22e Régiment of the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade,[9] 1st Commonwealth Division. Major fought in the First Battle of Maryang San where he received a bar to his Distinguished Conduct Medal[10] for capturing and holding a key hill in November 1951.

Hill 355, nicknamed Little Gibraltar, was a strategic feature, commanding the terrain for twenty miles around, so the Communists were determined to take it before the truce talks came to an agreement which would lock each side into their present positions. Hill 355 was held by the 3rd US Infantry Division, who linked up with the Canadian's Royal 22e Régiment on the Americans' western flank.[11] On November 22, the 64th Chinese Army (around 40,000 men) began their attack: over the course of two days, the Americans were pushed back from Hill 355 by elements of the Chinese 190th and 191st Divisions. The 3rd US Infantry Division tried to recapture the hill, but without any success, and the Chinese had moved to the nearby Hill 227, practically surrounding the Canadian forces.[12]

To relieve pressure, an elite scout and sniper team led by Léo Major was brought up. Armed with Sten guns, Major and his 18 men silently crept up Hill 355. At a signal, Major's men opened fire, panicking the Chinese who were trying to understand why the firing was coming from the center of their troops instead of from the outside. By 12:45 am, they had retaken the hill. However, an hour later, two Chinese divisions (the 190th and the 191st, totaling around 14,000 men) counter-attacked. Major was ordered to retreat, but refused and found scant cover for his men. He held the enemy off throughout the night, though they were so close to him that Major's own mortar bombs were practically falling on him. The commander of the mortar platoon, Captain Charly Forbes, later wrote that Major was "an audacious man ... not satisfied with the proximity of my barrage and asks to bring it closer...In effect, my barrage falls so close that I hear my bombs explode when he speaks to me on the radio."[13]

Death and legacy

Major died in Longueuil on 12 October 2008 and was buried at the Last Post Fund National Field of Honour in Pointe-Claire, Quebec. He was survived by Pauline De Croiselle, his wife of 57 years; four children; and five grandchildren.[14] A documentary film about his exploits, Léo Major, le fantôme borgne, has been produced in Montreal (Qc).

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2006-07-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fowler, T. Robert (Fall 2008). "Army Biography: Private Leo Major, DCM and BAR" (PDF). Canadian Army Journal: 113–118.

- "Leo Major | Canadian soldier". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- Major, Jocelyn (December 2008). "Leo Major: L'Honneur d'un Canadien" (PDF). Histomag '44 (57): 12–23. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Atherton, Tony (May 7, 2005). "Divergent portraits of war". The Ottawa Citizen. canada.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007.

- "The legendary liberator of Zwolle - Excerpt » The Windmill news articles » goDutch". www.godutch.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16.

- "No. 37235". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 21 August 1945. p. 4266.

- Rae, Bob (26 April 1945). "D-Day Chaud Scout, Stubborn Man, Captures Zwolle On His Own Hook". The Maple Leaf. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Leo Major - TRF". www.kvacanada.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "No. 39467". The London Gazette. 12 February 1952. p. 866.

- National Archives of Canada, RG 24, Vol 18357, R22eR War Diary, Commander's Conference, 19 November 1951.

- "Leo Major - TRF". www.kvacanada.com.

- Charly Forbes, Fantassin (Sillery, Les Éditions du Septentrion, 1994) 315.

- Murphy, Jessica (October 19, 2008). "Decorated hero dies at 87". The Toronto Star. Toronto, Canada.