Koumbi Saleh

Koumbi Saleh, sometimes Kumbi Saleh is the site of a ruined medieval town in south east Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana Empire.

Koumbi Saleh | |

|---|---|

Site of medieval town | |

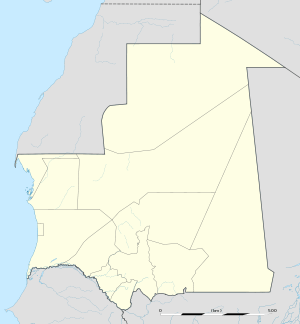

Koumbi Saleh Location within Mauritania | |

| Coordinates: 15°45′56″N 7°58′07″W | |

| Country | |

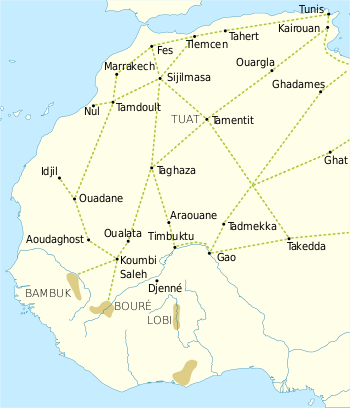

From the ninth century, Arab authors mention the Ghana Empire in connection with the trans-Saharan gold trade. Al-Bakri who wrote in eleventh century described the capital of Ghana as consisting of two towns 10 kilometres (6 mi) apart, one inhabited by Muslim merchants and the other by the king of Ghana. The discovery in 1913 of a 17th-century African chronicle that gave the name of the capital as Koumbi led French archaeologists to the ruins at Koumbi Saleh. Excavations at the site have revealed the ruins of a large Muslim town with houses built of stone and a congregational mosque but no inscription to unambiguously identify the site as that of capital of Ghana. Ruins of the king's town described by al-Bakri have not been found. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the site was occupied between the late 9th and 14th centuries.

Arabic sources and the capital of the Ghana Empire

The earliest author to mention Ghana is the Persian astronomer Ibrahim al-Fazari who, writing at the end of the eighth century, refers to "the territory of Ghana, the land of gold".[1] The Ghana Empire lay in the Sahel region to the north of the West African gold fields and was able to profit from controlling the trans-Saharan gold trade. The early history of Ghana is unknown but there is evidence that North Africa had begun importing gold from West Africa before the Arab conquest in the middle of the seventh century.[2]

In the medieval Arabic sources the word "Ghana" can refer to a royal title, the name of a capital city or a kingdom.[3] The earliest reference to Ghana as a town is by al-Khuwarizmi who died in around 846 AD.[4][5] Two centuries later a detailed description of the town is provided by al-Bakri in his Book of Routes and Realms which he completed in around 1068. Al-Bakri never visited the region but obtained his information from earlier writers and from informants that he met in his native Spain:

The city of Ghāna consists of two towns situated on a plain. One of these towns, which is inhabited by Muslims, is large and possesses twelve mosques, in one of which they assemble for Friday prayer. ... In the environs are wells with sweet water, from which they drink and with which they grow vegetables. The king's town is six miles [10 km] distant from this one and bears the name of Al-Ghāba. Between these two towns are continuous habitations. The houses of the inhabitants are of stone and acacia wood. The king has a palace and a number of domed dwellings all surrounded with an enclosure like a city wall. In the king's town, and not far from his courts of justice, is a mosque where Muslims who arrive in his court pray. Around the king's town are domed buildings and groves and thickets where the sorcerers of these people, men in charge of the religious cult, live.[6]

The descriptions provided by the early Arab authors lack sufficient detail to pinpoint the exact location of the town. In fact, the sources appear contradictory with al-Idrisi placing the town on both sides of the Niger River.[4][7][8] This has led to the suggestion that at some point the capital may have been moved south to the Niger River.[9] The much later 17th-century African chronicle, the Tarikh al-fattash, states that the Malian Empire was preceded by the Kayamagna dynasty which had a capital at a town called Koumbi.[10] The chronicle does not use the word Ghana. The other important 17th-century chronicle, the Tarikh al-Sudan mentions that the Malian Empire came after the dynasty of Qayamagha which had its capital at the city of Ghana.[11] It is assumed that the "Kayamagna" or "Qayamagha" dynasty ruled the empire of Ghana mentioned in the early Arabic sources.[12]

In the French translation of the Tarikh al-fattash published in 1913, Octave Houdas and Maurice Delafosse include a footnote in which they comment that local tradition also suggested that the first capital of Kayamagna was at Koumbi and that the town was in the Ouagadougou region, northeast of Goumbou on the road leading from Goumbou to Néma and Oualata.[13]

The Soninke Wangara exchanged salt for Bambuk gold, though they kept the source of the gold a secret from Muslim traders, with whom they exchanged the gold for clothing and other Maghrib goods. The king received one dinar of gold for each load of Saharn salt imported from the north, and two for each load exported to the south, keeping each gold nugget for himself. Muslim secretaries were employed to keep records of the taxable trade. Yet, in the 11th and 12th centuries, the Bure goldfields were developed, so that by the end of the 12th century, Ghana no longer dominated the gold trade. The Soninke farmers and traders then settled further south and west in the early 13th century.[14][15]

Archaeological site

The extensive ruins at Koumbi Saleh were first reported by Albert Bonnel de Mézières in 1914.[16] The site lies in the Sahel region of southern Mauritania, 30 km north of the Malian border, 57 km south-southeast of Timbédra and 98 km northwest of the town of Nara in Mali. The vegetation is low grass with thorny scrub and the occasional acacia tree. In the wet season (July–September) the limited rain fills a number of depressions, but for the rest of the year there is no rain and no surface water.

Beginning with Bonnel de Mézières in 1914, the site has been excavated by successive teams of French archaeologists. Paul Thomassey and Raymond Mauny excavated between 1949 and 1951,[17][18] Serge Robert during 1975-76 and Sophie Berthier during 1980–81.[19]

The main section of the town lay on a small hill that nowadays rises to about 15 m above the surrounding plain. The hill would have originally been lower as part of the present height is a result of the accumulated ruins.[20] The houses were constructed from local stone (schist) using banco rather than mortar.[21] From the quantity of debris it is likely that some of the buildings had more than one storey.[22] The rooms were quite narrow, probably due to the absence of large trees to provide long rafters to support the ceilings.[23] The houses were densely packed together and separated by narrow streets. In contrast a wide avenue, up to 12 m in width, ran in an east–west direction across the town. At the western end lay an open site that was probably used as a marketplace.[24] The main mosque was centrally placed on the avenue. It measured approximately 46 m east to west and 23 m north to south. The western end was probably open to the sky. The mihrab faced due east.[25] The upper section of the town covered an area of 700 m by 700 m. To the southwest lay a lower area (500 m by 700 m) that would have been occupied by less permanent structures and the occasional stone building.[26] There were two large cemeteries outside the town suggesting that the site was occupied over an extended period. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal fragments from a house near the mosque have given dates that range between the late 9th and the 14th centuries.[27] The French archaeologist Raymond Mauny estimated that the town would have accommodated between 15,000 and 20,000 inhabitants.[24][28] Mauny himself acknowledged that this is an enormous population for a town in the Sahara with a very limited supply of water ("Chiffre énorme pour une ville saharienne").[24]

The archaeological evidence suggests that Koumbi Saleh was a Muslim town with a strong Maghreb connection. No inscription has been found to unambiguously link the ruins with the Muslim capital of Ghana described by al-Bakri. Moreover, the ruins of the king's town of Al-Ghaba have not been found.[29] This has led some historian to doubt the identification of Koumbi Saleh as the capital of Ghana.[30][31]

World Heritage Status

The archaeological site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on June 14, 2001 in the Cultural category.[32]

Notes

- Mauny 1954, p. 201.

- Garrard 1982, p. 450.

- Masonen 2000, p. 516.

- Mauny 1954, p. 205.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 7.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 79–80. A translation into French is available online: El-Bekri 1913, p. 328.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 109, 390 note 8.

- Masonen 2000, p. 355.

- Levtzion 1973, pp. 46-47.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, pp. 75-76.

- Hunwick 2003, p. 13.

- Hunwick 2003, p. 13 note 1.

- Houdas & Delafosse 1913, p. 76 note 2.

- Meredith, Martin (2014). The Fortunes of Africa. New York: Public Affairs. p. 71,75. ISBN 9781610396356.

- Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 89, 92–93. ISBN 9780230308473.

- Bonnel de Mézière 1914.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1951.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1956.

- Berthier 1997.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1951, p. 439.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1951, pp. 440 note 4, 449.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1951, p. 447.

- Thomassey & Mauny 1951, p. 449 note 1.

- Mauny 1961, p. 482.

- Mauny 1961, pp. 472-473.

- Mauny 1961, p. 481.

- Berthier 1997, p. 21.

- Levtzion 1973, pp. 23-24.

- Mauny 1954, p. 207.

- Masonen 2000, p. 523.

- Insoll 1999, p. 84.

- Site archéologique de Kumbi Saleh (in French), UNESCO – World Heritage Convention, 14 June 2001, retrieved 8 October 2011.

References

- Berthier, Sophie (1997), Recherches archéologiques sur la capitale de l'empire de Ghana: Etude d'un secteur, d'habitat à Koumbi Saleh, Mauritanie: Campagnes II-III-IV-V (1975–1976)-(1980–1981), British Archaeological Reports 680, Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 41 (in French), Oxford: Archaeopress, ISBN 0-86054-868-6.

- Bonnel de Mézière, Albert (1914), "Note sur ses récentes découvertes, d'après un télégramme adressé par lui, le 23 mars 1914, à M. le gouverneur Clozel", Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French), 58 (3): 253–257, doi:10.3406/crai.1914.73397.

- El-Bekri (1913) [1859], Description de l'Afrique septentrionale (in French), Mac Guckin de Slane, trans. and ed., Algers: A. Jourdan.

- Garrard, Timothy F. (1982), "Myth and metrology: the early trans-Saharan gold trade", Journal of African History, 23 (4): 443–461, doi:10.1017/s0021853700021290, JSTOR 182035.

- Houdas, Octave; Delafosse, Maurice, eds. (1913), Tarikh el-fettach par Mahmoūd Kāti et l'un de ses petit fils (2 Vols.), Paris: Ernest Leroux. Volume 1 is the Arabic text, Volume 2 is a translation into French. Reprinted by Maisonneuve in 1964 and 1981. The French text is also available from Aluka but requires a subscription.

- Hunwick, John O. (2003), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-12560-4. First published in 1999 as ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Insoll, Timothy (1999), "Review of: Recherches Archéologiques sur la Capitale de l'Empire de Ghana by Sophie Berthier", African Archaeological Review, 16 (1): 83–85, JSTOR 25115527.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0-8419-0431-6. Reprinted by Holmes & Meier in 1980.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 1-55876-241-8. First published in 1981.

- Masonen, Pekka (2000), The Negroland revisited: Discovery and invention of the Sudanese middle ages, Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, ISBN 951-41-0886-8.

- Mauny, R.A. (1954), "The question of Ghana", Journal of the International African Institute, 24 (3): 200–213, JSTOR 1156424.

- Mauny, Raymond (1961), Tableau géographique de l'ouest africain au moyen age, d’après les sources écrites, la tradition et l'archéologie (in French), Dakar: Institut français d'Afrique Noire. Includes a detailed plan of the archaeological site as Figure 95 on page 480.

- Thomassey, Paul; Mauny, Raymond (1951), "Campagne de fouilles à Koumbi Saleh", Bulletin de l'Institut Français de l'Afrique Noire (B) (in French), 13: 438–462, archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

- Thomassey, Paul; Mauny, Raymond (1956), "Campagne de fouilles de 1950 à Koumbi Saleh (Ghana?)", Bulletin de l'Institut Français de l'Afrique Noire (B) (in French), 18: 117–140.

Further reading

- Burkhalter, Sheryl L. (1992), "Listening for Silences in Almoravid History: another reading of 'The Conquest That Never Was'", History in Africa, 19: 103–131, JSTOR 3171996.

- van Doosselaere, Barbara (2014), Le Roi et le Potier: Etude technologique de l'assemblage céramique de Koumbi Saleh, Mauritanie (5e/6e - 17e siècles AD), Reports in African Archaeology 5 (in French), Frankfurt am Main: Africa Magna Verlag, ISBN 978-3-937248-43-1.

- Conrad, David C.; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1982), "The conquest that never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076. I. The external Arabic sources", History in Africa, 9: 21–59, JSTOR 3171598.

- Conrad, David C.; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1983), "The conquest that never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076. II. The local oral sources", History in Africa, 10: 53–78, JSTOR 3171690.

- Delafosse, Maurice (1916), "La question de Ghana et la Mission Bonnel de Mézières", Annuaire et Mémoires du Comité d'Etudes historiques et scientifique de l'AOF: 40–61.

- Masonen, Pekka; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1966), "Not quite Venus from the waves: The Almoravid conquest of Ghana in the modern historiography of Western Africa" (PDF), History in Africa, 23: 197–232, doi:10.2307/3171941, JSTOR 3171941.

- Fisher, Humphrey J. (1982), "Early Arabic sources and the Almoravid conquest of Ghana", Journal of African History, 23: 549–560, doi:10.1017/s0021853700021356, JSTOR 182041.

- Robert, D.; Robert, S. (1972), "Douze années de recherches archéologique en république islamique de Mauritanie", Annales de la faculté de lettres et sciences humaines (Université de Dakar) (in French), 2: 195–214.

External links

- Map showing Koumbi Saleh: Fond Typographique Sheet ND-29-XXIII 1:200,000 Nara, République Islamique de Mauritanie, archived from the original on 2012-04-26.