Kirchhoff's diffraction formula

Kirchhoff's diffraction formula[1][2] (also Fresnel–Kirchhoff diffraction formula) can be used to model the propagation of light in a wide range of configurations, either analytically or using numerical modelling. It gives an expression for the wave disturbance when a monochromatic spherical wave passes through an opening in an opaque screen. The equation is derived by making several approximations to the Kirchhoff integral theorem which uses Green's theorem to derive the solution to the homogeneous wave equation.

Derivation of Kirchhoff's diffraction formula

Kirchhoff's integral theorem, sometimes referred to as the Fresnel–Kirchhoff integral theorem,[3] uses Green's identities to derive the solution to the homogeneous wave equation at an arbitrary point P in terms of the values of the solution of the wave equation and its first order derivative at all points on an arbitrary surface which encloses P.

The solution provided by the integral theorem for a monochromatic source is:

where U is the complex amplitude of the disturbance at the surface, k is the wavenumber, and s is the distance from P to the surface.

The assumptions made are:

- U and ∂U/∂n are discontinuous at the boundaries of the aperture,

- the distance to the point source and the dimension of opening S are much greater than λ.

Point source

Consider a monochromatic point source at P0, which illuminates an aperture in a screen. The energy of the wave emitted by a point source falls off as the inverse square of the distance traveled, so the amplitude falls off as the inverse of the distance. The complex amplitude of the disturbance at a distance r is given by

where a represents the magnitude of the disturbance at the point source.

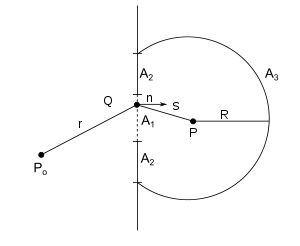

The disturbance at a point P can be found by applying the integral theorem to the closed surface formed by the intersection of a sphere of radius R with the screen. The integration is performed over the areas A1, A2 and A3, giving

To solve the equation, it is assumed that the values of U and ∂U/∂n in the area A1 are the same as when the screen is not present, giving at Q:

where r is the length P0Q, and (n, r) is the angle between P0Q and the normal to the aperture.

Kirchhoff assumes that the values of U and ∂U/∂n in A2 are zero. This implies that U and ∂U/∂n are discontinuous at the edge of the aperture. This is not the case, and this is one of the approximations used in deriving the equation.[4][5] These assumptions are sometimes referred to as Kirchhoff's boundary conditions.

The contribution from A3 to the integral is also assumed to be zero. This can be justified by making the assumption that the source starts to radiate at a particular time, and then by making R large enough, so that when the disturbance at P is being considered, no contributions from A3 will have arrived there.[1] Such a wave is no longer monochromatic, since a monochromatic wave must exist at all times, but that assumption is not necessary, and a more formal argument avoiding its use has been derived.[6]

We have

where (n, s) is the angle between the normal to the aperture and PQ.

Finally, the terms 1/r and 1/s are assumed to be negligible compared with k, since r and s are generally much greater than 2π/k, which is equal to the wavelength. Thus, the integral above, which represents the complex amplitude at P, becomes

This is the Kirchhoff or Fresnel–Kirchhoff diffraction formula.

Equivalence to Huygens–Fresnel equation

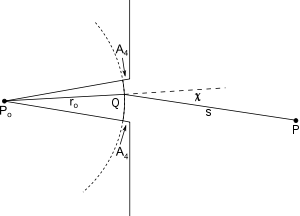

The Huygens–Fresnel principle can be derived by integrating over a different closed surface. The area A1 above is replaced by a wavefront from P0, which almost fills the aperture, and a portion of a cone with a vertex at P0, which is labeled A4 in the diagram. If the radius of curvature of the wave is large enough, the contribution from A4 can be neglected. We also have

where χ is as defined in Huygens–Fresnel principle, and cos(n, r) = 1. The complex amplitude of the wavefront at r0 is given by

The diffraction formula becomes

This is the Kirchhoff's diffraction formula, which contains parameters that had to be arbitrarily assigned in the derivation of the Huygens–Fresnel equation.

Extended source

Assume that the aperture is illuminated by an extended source wave.[7] The complex amplitude at the aperture is given by U0(r).

It is assumed, as before, that the values of U and ∂U/∂n in the area A1 are the same as when the screen is not present, that the values of U and ∂U/∂n in A2 are zero (Kirchhoff's boundary conditions) and that the contribution from A3 to the integral are also zero. It is also assumed that 1/s is negligible compared with k. We then have

This is the most general form of the Kirchhoff diffraction formula. To solve this equation for an extended source, an additional integration would be required to sum the contributions made by the individual points in the source. If, however, we assume that the light from the source at each point in the aperture has a well-defined direction, which is the case if the distance between the source and the aperture is significantly greater than the wavelength, then we can write

where a(r) is the magnitude of the disturbance at the point r in the aperture. We then have

and thus

Fraunhofer and Fresnel diffraction equations

In spite of the various approximations that were made in arriving at the formula, it is adequate to describe the majority of problems in instrumental optics. This is mainly because the wavelength of light is much smaller than the dimensions of any obstacles encountered. Analytical solutions are not possible for most configurations, but the Fresnel diffraction equation and Fraunhofer diffraction equation, which are approximations of Kirchhoff's formula for the near field and far field, can be applied to a very wide range of optical systems.

One of the important assumptions made in arriving at the Kirchhoff diffraction formula is that r and s are significantly greater than λ. A further approximation can be made, which significantly simplifies the equation further: this is that the distances P0Q and QP are much greater than the dimensions of the aperture. This allows one to make two further approximations:

- cos(n, r) − cos(n, s) is replaced with 2cos β, where β is the angle between P0P and the normal to the aperture. The factor 1/rs is replaced with 1/r's', where r' and s' are the distances from P0 and P to the origin, which is located in the aperture. The complex amplitude then becomes:

- Assume that the aperture lies in the xy plane, and the coordinates of P0, P and Q (a general point in the aperture) are (x0, y0, z0), (x, y, z) and (x', y', 0) respectively. We then have:

We can express r and s as follows:

These can be expanded as power series:

The complex amplitude at P can now be expressed as

where f(x', y') includes all the terms in the expressions above for s and r apart from the first term in each expression and can be written in the form

where the ci are constants.

Fraunhofer diffraction

If all the terms in f(x', y') can be neglected except for the terms in x' and y', we have the Fraunhofer diffraction equation. If the direction cosines of P0Q and PQ are

The Fraunhofer diffraction equation is then

where C is a constant. This can also be written in the form

where k0 and k are the wave vectors of the waves traveling from P0 to the aperture and from the aperture to P respectively, and r' is a point in the aperture.

If the point source is replaced by an extended source whose complex amplitude at the aperture is given by U0(r' ), then the Fraunhofer diffraction equation is:

where a0(r') is, as before, the magnitude of the disturbance at the aperture.

In addition to the approximations made in deriving the Kirchhoff equation, it is assumed that

- r and s are significantly greater than the size of the aperture,

- second- and higher-order terms in the expression f(x', y') can be neglected.

Fresnel diffraction

When the quadratic terms cannot be neglected but all higher order terms can, the equation becomes the Fresnel diffraction equation. The approximations for the Kirchhoff equation are used, and additional assumptions are:

- r and s are significantly greater than the size of the aperture,

- third- and higher-order terms in the expression f(x', y') can be neglected.

References

- Born, Max; Wolf, Emil (1999). Principles of optics: electromagnetic theory of propagation, interference and diffraction of light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 986. ISBN 9780521642224.

- Longhurst, Richard Samuel (1986). Geometrical And Physical Optics. Orient BlackSwan. p. 651. ISBN 8125016236.

- Kirchhoff, G. (1883). "Zur Theorie der Lichtstrahlen". Annalen der Physik (in German). Wiley. 254 (4): 663–695. Bibcode:1882AnP...254..663K. doi:10.1002/andp.18832540409.

- J.Z. Buchwald & C.-P. Yeang, "Kirchhoff's theory for optical diffraction, its predecessor and subsequent development: the resilience of an inconsistent theory", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, vol. 70, no. 5 (Sep. 2016), pp. 463–511; doi:10.1007/s00407-016-0176-1.

- J. Saatsi & P. Vickers, "Miraculous success? Inconsistency and untruth in Kirchhoff’s diffraction theory", British J. for the Philosophy of Science, vol. 62, no. 1 (March 2011), pp. 29–46; jstor.org/stable/41241806. (Pre-publication version, with different pagination: dro.dur.ac.uk/10523/1/10523.pdf.)

- M. Born, Optik: ein Lehrbuch der elektromagnetischen Lichttheorie. Berlin, Springer, 1933, reprinted 1965, p. 149.

- M. V. Klein & T. E. Furtak, 1986, Optics; 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York ISBN 0-471-87297-0.

Further reading

- Baker, B.B.; Copson, E.T. (1939, 1950). The Mathematical Theory of Huygens' Principle. Oxford.

- Woan, Graham (2000). The Cambridge Handbook of Physics Formulas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521575072.

- Griffiths, David J. (2012). Introduction to Electrodynamics. Pearson Education, Limited. ISBN 978-0-321-85656-2.

- Band, Yehuda B. (2006). Light and Matter: Electromagnetism, Optics, Spectroscopy and Lasers. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-89931-0.

- Kenyon, Ian (2008). The Light Fantastic: A Modern Introduction to Classical and Quantum Optics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856646-5.

- Lerner, Rita G.; George L., Trigg (1991). Encyclopedia of physics. VCH. ISBN 978-0-89573-752-6.

- Sybil P., Parker (1993). MacGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Physics. McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Limited. ISBN 978-0-07-051400-3.