Keto–enol tautomerism

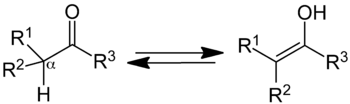

In organic chemistry, keto–enol tautomerism refers to a chemical equilibrium between a keto form (a ketone or an aldehyde) and an enol (an alcohol). The keto and enol forms are said to be tautomers of each other. The interconversion of the two forms involves the movement of an alpha hydrogen atom and the reorganisation of bonding electrons; hence, the isomerism qualifies as tautomerism.

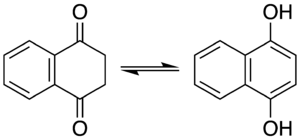

Keto form (left); enol form (right).

A compound containing a carbonyl group (C=O) is normally in rapid equilibrium with an enol tautomer, which contains a pair of doubly bonded carbon atoms adjacent to a hydroxyl (−OH) group, C=C-OH. The keto form predominates at equilibrium for most ketones. Nonetheless, the enol form is important for some reactions. The deprotonated intermediate in the interconversion of the two forms, referred to as an enolate anion, is important in carbonyl chemistry, in large part because it is a strong nucleophile.

Normally, the keto–enol tautomerization chemical equilibrium is highly thermodynamically driven, and at room temperature the equilibrium heavily favors the formation of the keto form. A classic example for favoring the keto form can be seen in the equilibrium between vinyl alcohol and acetaldehyde (K = [enol]/[keto] ≈ 3 × 10−7). However, it is reported that in the case of vinyl alcohol, formation of a stabilized enol form can be accomplished by controlling the water concentration in the system and utilizing the kinetic favorability of the deuterium-produced kinetic isotope effect (kH+/kD+ = 4.75, kH2O/kD2O = 12). Deuterium stabilization can be accomplished through hydrolysis of a ketene precursor in the presence of a slight stoichiometric excess of heavy water (D2O). Studies show that the tautomerization process is significantly inhibited at ambient temperatures ( kt ≈ 10−6 M/s), and the half-life of the enol form can easily be increased to t1/2 = 42 minutes for first-order hydrolysis kinetics.[1]

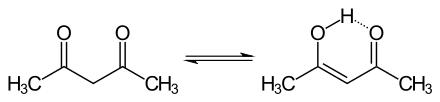

Another exception is the 1,3-diketones, such as acetylacetone (2,4-pentanedione), which favor the enol form.

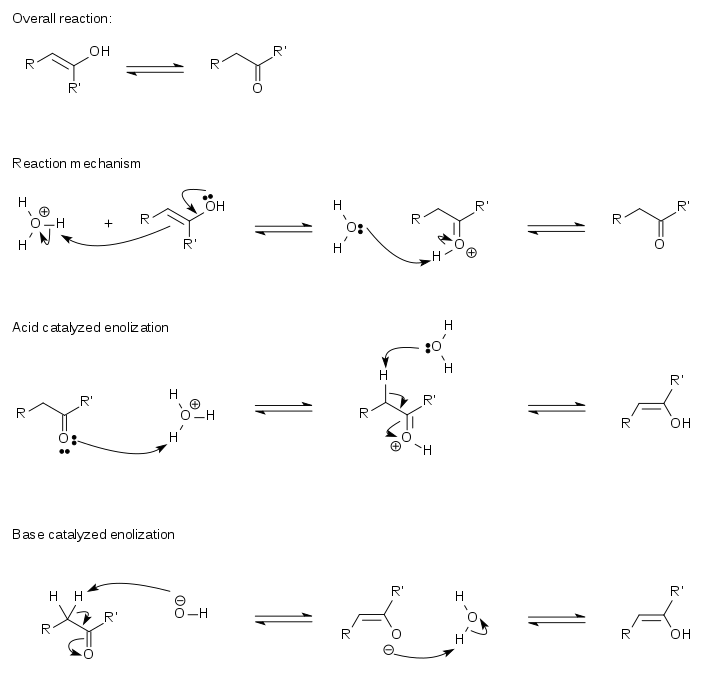

Mechanism

The acid catalyzed conversion of an enol to the keto form proceeds by a two-step mechanism in an aqueous acidic solution. For this, it is necessary that the alpha carbon atom (the carbon atom closest to the functional group) contains at least one hydrogen atom known as the alpha hydrogen atom. This alpha hydrogen atom must additionally be positioned such that it may line up parallel with the antibonding pi-orbital of the carbonyl group. The hyperconjugation of this bond with the C–H bond at the alpha carbon atom reduces the electron density of the C–H bond and weakens it, making the alpha hydrogen atom more acidic. When the alpha hydrogen atom is not aligned with the pi orbital, for example in the adamantanone or other polycyclic ketones, the enolization is impossible or very slow.[2][3]

In the first step of the mechanism, the exposed electrons of the C=C double bond of the enol are donated to a hydronium ion (H3O+). This addition follows Markovnikov's rule, thus the proton is added to the carbon atom with more attached hydrogen atoms. This is a concerted step with the oxygen atom in the hydroxyl group donating electrons to produce the eventual carbonyl group.

Erlenmeyer rule

One of the early investigators into keto–enol tautomerism was Emil Erlenmeyer. His Erlenmeyer rule, developed in 1880, states that all alcohols in which the hydroxyl group is attached directly to a double-bonded carbon atom become aldehydes or ketones. This conversion occurs because the keto form is, in general, more stable than its enol tautomer. The keto form is therefore favored at equilibrium because it is the lower energy form.

Stereochemistry of ketonization

If R1 and R2 (note equation at top of page) are different substituents, there is a new stereocenter formed at the alpha position when an enol converts to its keto form. Depending on the nature of the three R groups, the resulting products in this situation would be diastereomers or enantiomers.

Phenols

In certain aromatic compounds such as phenol, the enol is important due to the aromatic character of the enol but not the keto form. Melting the naphthalene derivative naphthalene-1,4-diol, which has the 1,4-diol as part of an aromatic ring, at 200 °C results in a 2:1 mixture with the diketo form (naphthalene-1,4-dione), where the ring with the oxygen atoms has become non-aromatic. Heating the diketo form in benzene at 120 °C for three days also affords a mixture (1:1 with first-order reaction kinetics). The diketo product is kinetically stable and reverts to the dienol in presence of a base. The diketo form can be obtained in a pure form by stirring the diketo form in trifluoroacetic acid and toluene (1:9 ratio) followed by recrystallisation from isopropyl ether.[4]

When the enol form is complexed with chromium tricarbonyl, complete conversion to the keto form accelerates and occurs even at room temperature in benzene.

Significance in biochemistry

Keto–enol tautomerism is important in several areas of biochemistry. The high phosphate-transfer potential of phosphoenolpyruvate results from the fact that the phosphorylated compound is "trapped" in the less thermodynamically favorable enol form, whereas after dephosphorylation it can assume the keto form. Rare enol tautomers of the bases guanine and thymine can lead to mutation because of their altered base-pairing properties.[5]

DNA

Keto–enol and the analogous amino–imino tautomerism are among the primary causes of spontaneous mutations during DNA replication and repair. In deoxyribonucleic acids (DNA), the nucleotide bases are usually in the keto form, which is stabilized by the hydrogen bonding that holds together the two strands of the DNA double-helix. Single-stranded DNA exists transiently during replication, and there a rare shift to the enol form of thymine (T) or guanine (G) can occur. If the position of the enol base is replicated before it reverts to keto configuration, the result is incorporation of a mismatched base. For example, the tautomeric shift of keto-guanine to enol-guanine (G*) causes it to pair with thymine rather than its normal partner, cytosine. The tautomeric shift is transient and following reversion to the keto form the resulting mismatched nucleotide is usually detected and removed, but in cases of DNA damage or rapid replication, the mismatch may give rise to a permanent sequence change, a transition mutation.

The initial models of DNA constructed by James Watson and Francis Crick envisioned the bases to be in their enol tautomeric form until corrected by Jerry Donohue. This mistaken understanding delayed their solving the structure of DNA until corrected.[6] As a consequence, though, they were the first to recognize the potential role of tautomerism in spontaneous mutation.

See also

- Geminal diol, another form of ketones and aldehydes in water solutions

- Regioselectivity

References

- Investigations into the Chemistry of Thermodynamically Unstable Species. The Direct Polymerization of Vinyl Alcohol, the Enolic Tautomer of Acetaldehyde. Anna K. Cederstav and Bruce M. Novak. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1994, Volume 100 Pages 4073–74.

- Norlander, J.E.; Jindal, S.; Kitko, D. (1969). "Resistance of adamantanone to homoenolization". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications: 1136–1137. doi:10.1039/C29690001136.

- Stothers, J.B.; Tan, C.T. (1974). "Adamantanone: stereochemistry of its homoenolization as shown by 2H nuclear magnetic resonance". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (18): 378–379. doi:10.1039/C39740000738.

- Rediscovery, Isolation, and Asymmetric Reduction of 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydronaphthalene-1,4-dione and Studies of its [Cr(CO)3] Complex E. Peter Kündig, Alvaro Enríquez García, Thierry Lomberget, Gérald Bernardinelli Angewandte Chemie International Edition Volume 45, Issue 1, Pages 98–101 2006 doi:10.1002/anie.200502588

- Wang, W., H. W. Hellinga, et al. (2011). "Structural evidence for the rare tautomer hypothesis of spontaneous mutagenesis." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(43): 17644-17648.

- The Eighth Day of Creation. Judson, Horace Freeland. Simon & Schuster, NY:1979.