Hoplodactylus delcourti

Hoplodactylus delcourti, also commonly known as kawekaweau,[3] Delcourt's sticky-toed gecko[4] or Delcourt's giant gecko, is an extinct species of lizard, the largest known of all geckos with a snout-to-vent length (SVL) of 370 mm (14.6 in) and an overall length (including tail) of at least 600 mm (23.6 in).[5] It was perhaps endemic to New Zealand, where it may have been called kawekaweau.[1][lower-alpha 1] The idea that Hoplodactylus delcourti is the kawekaweau of Maori tradition has been contested.[8][9][10]

| Hoplodactylus delcourti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Diplodactylidae |

| Genus: | Hoplodactylus |

| Species: | †H. delcourti |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hoplodactylus delcourti | |

History

According to his own report, in 1870, a Māori chief killed a kawekaweau he found under the bark of a dead rata tree in the forests of the Waimana Valley,[3] (now protected as part of the northern section of Te Urewera National Park[11]). This is the only documented report of anyone ever seeing one of these animals alive.[3] He described it as being "brownish with reddish stripes and as thick as a man's wrist". Whether his story was true or not is unknown. A single stuffed museum specimen was "discovered" in the basement of the Natural History Museum of Marseille in 1986;[7] however, the origins and date of collection of the specimen remain a mystery, as when it was found, it was not labelled.[3] Scientists examining it have suggested that it was from New Zealand and was in fact the lost "kawekaweau", a giant and mysterious forest lizard of Maori oral tradition. Attempts to extract DNA from the sole specimen in 1994 were unsuccessful[12] though ancient DNA technology has significantly advanced since then. Trevor Worthy suggests that the specimen originated on an island of New Caledonia rather than New Zealand, due to a lack of fossil evidence.[10]

Etymology

This animal's specific epithet, delcourti, is taken from the surname of French museum worker Alain Delcourt, who discovered the forgotten specimen in the basement of the Natural History Museum of Marseille.[4][7]

Notes

- The largest extant species of gecko is Leach's giant gecko of New Caledonia, at 360 mm (14.2 in) long;[6] the Duvaucel's gecko is the largest surviving species of gecko in New Zealand, also one of the largest in the world.[7]

References

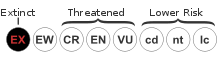

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Hoplodactylus delcourti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T10254A3185278. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T10254A3185278.en.

- "Hoplodactylus delcourti ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- Bauer AM, Russell AP (1986). "Hoplodactylus delcourti n. sp. (Reptilia: Gekkonidae), the largest known gecko" Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, New Zealand Journal of Zoology 13: 141–148. doi:10.1080/03014223.1986.10422655

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Hoplodactylus delcourti, p. 69).

- Wilson, K.-J. (2004). Flight of the Huia: Ecology and Conservation of New Zealand's Frogs, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals. Canterbury University Press. ISBN 0-908812-52-3. OCLC 937349394.

- Ballance, Allison; Morris, Rod (2003). Island Magic; Wildlife of the South Seas. David Bateman Publishing.

- Gill, Brian; Whitaker, Tony (1996). New Zealand Frogs and Reptiles. David Bateman Publishing. ISBN 978-1869532642.

- Worthy, T. H. (March 1997). "Quaternary fossil fauna of South Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 27 (1): 67–162. doi:10.1080/03014223.1997.9517528.

- Tennyson, Alan J. D. (2010). "The origin and history of New Zealand's terrestrial vertebrates" (PDF). New Zealand Ecological Society. 34 (1): 6–27.

- Worthy, Trevor H. (2016), "A Review of the Fossil Record of New Zealand Lizards", New Zealand Lizards, Springer International Publishing, pp. 65–86, ISBN 978-3-319-41672-4, retrieved 2020-04-10

- "Waimana Valley tracks". New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- Cooper, Alan (1994), Herrmann, Bernd; Hummel, Susanne (eds.), "DNA from Museum Specimens", Ancient DNA: Recovery and Analysis of Genetic Material from Paleontological, Archaeological, Museum, Medical, and Forensic Specimens, Springer, pp. 149–165, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4318-2_10, ISBN 978-1-4612-4318-2, retrieved 2020-04-03

| Wikispecies has information related to Hoplodactylus delcourti |