Julia Maesa

Julia Maesa (7 May before 160 AD – c. 224 AD) was a member of the Severan dynasty of the Roman Empire who was the major power behind the throne in the reigns of her grandsons, Elagabalus and Severus Alexander,[1] as Augusta of the Empire from 218 to her death.[2] Born in Emesa, Syria (modern day Homs), Maesa was the daughter of the high priest of Emesa's Temple of the Sun, and the elder sister of Roman empress Julia Domna.

| Julia Maesa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augusta | |||||||||

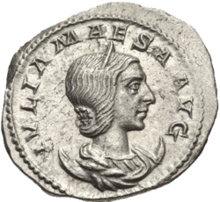

Antoninianus of Julia Maesa | |||||||||

| Born | 7 May before c. 160 Emesa, Syria | ||||||||

| Died | After 224 Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Spouse | Julius Avitus | ||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | Royal family of Emesa | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Severan dynasty | ||||||||

| Father | Julius Bassianus | ||||||||

Through her sister's marriage, Maesa became sister-in-law to Septimius Severus and aunt of Caracalla and Geta, who all became emperors. She herself married fellow Syrian Julius Avitus, who was of consular rank.[3][4] She bore him two daughters, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea,[1] who became mothers of Elagabalus and Severus Alexander respectively.[3]

The Severan dynasty was dominated by powerful women, one of which was Maesa. Politically able and ruthless, she contended for political power after her sister's suicide.[1] She is best known for her plotting and scheming which resulted in the restoration of the Severan dynasty to the Roman throne after the assassination of Caracalla and the usurpation of the throne by Macrinus.[5] Afterwards she held power until she died in Rome.[6] She was later deified in Syria along with her sister.[7][3] The Severan dynasty ended in 235.[8]

Early life and marriage

Julia Maesa was born in 7 May[7] before around 160AD, the elder daughter of the priest Julius Bassianus in Emesa, Syria, modern day Homs.[9] She had a younger sister, Julia Domna who would later become Roman empress after her marriage to Septimius Severus who was by the time of their marriage a senator.[10]

As Maesa was an Arab,[11][2] her cognomen, Maesa, is the feminine nomen agentis of the Arabic verb "masa" which signifies walking with a swinging gait.[12][2] This would be an appropriate female name as the verb from which it was derived was used by Arab poets to describe the figures of the women that they write about.[12] Although no written account describing her appearance survives, her sharp and formidable features, which contradict the soft and sensitive ones of her sister,[13] are well displayed on the coins minted during the reign of her grandchildren.[3]

Maesa later married a fellow Syrian, Julius Avitus, a consul who also served as provincial governor in the empire.[3] She bore him two daughters, her eldest daughter, Julia Soaemias, was born around 180 AD[14] or some time before,[15] and was followed by another daughter, Julia Mamaea not long after.[4]

Life in Rome

After her sister's arrival to Rome and the beginning of her tenure as empress consort, Maesa, accompanied by her family, traveled to Rome where they took up residence in the imperial court,[4] although her husband, Julius Avitus who held several important posts did not stay in Rome for long and had to make many travels across the empire, which she did not accompany him on.[15]

During their stay in Rome, Maesa and her family amassed extreme wealth and fortune,[16] and rose highly in the Roman government and court of Septimius Severus and later, his son and successor Caracalla.[4] Her two daughters attained a prominent position in court while their Syrian husbands held important posts as provincial governors and consuls,[17][4] with Maesa's own husband along with that of her daughter rising from the Equestrian rank to reach Senatorial rank.[17]

Return to Emesa

In 217 AD, after the murder of emperor Caracalla and the usurpation of the throne by Macrinus, Maesa's sister, Domna, now with none of the power or influence she held during the reigns of her husband and her son, suffering from breast cancer, and having lost both of her children, chose to commit suicide by starvation.[1][18]

Maesa and her family, who had resided in Rome for the last two decades,[4] were spared and ordered by Macrinus to leave Rome and return to their home town of Emesa in Syria,[16][4] likely because Macrinus wanted to avoid any action that would seem disloyal to Caracalla's memory to avoid any reprisals from the army.[4] Macrinus made the crucial mistake of leaving Maesa's great wealth, amassed over a period of over 20 years intact,[4][16] a decision which Macrinus would regret not long after.[15]

Maesa, who arrived in Emesa sometime between spring 217 and spring 218,[17] vowed revenge,[19] and Domna's suicide was still far off from ending the influence of the powerful women of the family.[1]

Restoration of the Severan dynasty

Macrinus was in a difficult position after Caracalla's assassination and was struggling to gain legitimacy and maintain loyalty to his rule,[18][4] encouraging Maesa. Her location, Emesa, was close to a military base where many soldiers still held the Severans in high esteem and were loyal to the dynasty,[4] aside from their discontent over Macrinus' peace with the Parthians,[18] making it an excellent choice to launch a coup to restore her family to power.[4]

The first step was to choose a male candidate from within the family to replace the usurper.[4] Maesa's husband died in Cyprus shortly before 217,[4] as well as her eldest daughter's husband.[4] Julia Soaemias had a 14-year-old son, Varius Avitus Bassianus, who was the hereditary priest of the Emesan sun god,[18][4] and Maesa had a different future in mind for him.[4] He had begun attracting the soldiers of the Legio III Gallica stationed near Emesa, who would visit the city's temple occasionally to view the extravagant yet amusing religious rituals of Bassianus.[20]

Now even further encouraged by the attention of the soldiers, Maesa proceeded with her plot by trying to challenge the legitimacy of the new emperor Macrinus, and she did so by claiming that the 14-year-old, who greatly resembled Caracalla, was indeed the former emperor's bastard son and that Caracalla slept with both her daughters.[16][5] The claim that Bassianus was the love child of Caracalla and Soaemias, despite almost certainly being untrue,[20] was not so easily refuted, as aside from the young boy's resemblance to the emperor,[16] Soaemias had been living in the Roman court at the time of Caracalla's reign,[5] and Maesa seemed not to mind that this claim would be sacrificing the honor and reputation of her daughters as it was, after all, an effective move to further her plan.[21]

Julia Maesa began offering to distribute her great wealth and fortune to the loyal soldiers in exchange for their support,[5] news of which began to spread throughout the army camps.[20] Maesa, her daughter and Bassianus were taken into the army camp at night where the 14-year-old boy was immediately acknowledged and hailed as emperor by the soldiers and clad in imperial purple.[20]

Historian Cassius Dio narrates a slightly different version of events; he mentions a certain Gannys, who is not mentioned as partaking in the plot at any other source, as the main instigator of the revolt.[20] Allegedly a 'youth who has not yet reached manhood', Dio claims he was raised by Maesa and was Soaemias' lover and the protector of her son,[20] and at a certain night, dressed Bassianus in clothes worn by Caracalla as a child, took him to the army camp and claimed he was the murdered emperor's son without the knowledge of either Soaemias or Maesa.[20]

It is unlikely that Maesa and Soaemias, with much to gain from Bassianus becoming emperor, would be completely unaware of the actions of Gannys.[20] On the other hand, it is also unlikely that Maesa alone orchestrated the young boy's ascension. In her plan she probably had the support of many important figures from the city of Emesa and even some figures in Rome's ruling elite.[20]

Reaction of Macrinus

.jpg)

With the support of an entire legion, other legionnaires, prompted by discontent over pay, deserted Macrinus and joined Elagabalus' ranks as well. In response to the growing threat, Macrinus sent out a cavalry force under the command of Ulpius Julianus to try and regain control of the rebel soldiers. Rather than capturing the rebel forces, the cavalry instead killed Ulpius and defected to Elagabalus.[22][23]

Following these events, Macrinus traveled to Apamea to ensure the loyalty of Legio II Parthica before setting off to march against Emesa.[24] According to Dio, Macrinus appointed his son Diadumenian to the position of Imperator, and promised the soldiers 20,000 Sesterces each, with 4,000 of these to be paid on the spot. Dio further says that Macrinus hosted a dinner for the residents of Apamea in honour of Diadumenian.[25][26] At the dinner, Macrinus was supposedly presented with the head of Ulpius Julianus who had been killed by his soldiers.[25][27] In response, Macrinus left Apamea and headed south.[24]

Macrinus' and Elagabalus' troops met somewhere near the border of Syria Coele and Syria Phoenice. Despite Macrinus' efforts to quell the rebellion at this engagement, his whole legion defected to Elagabalus forcing Macrinus to retire to Antioch. Elagabus took to the offensive and marched on Antioch.[24]

Battle of Antioch

Elagabalus' armies, commanded by the inexperienced but determined Gannys, engaged Macrinus' Praetorian Guard in a narrowly fought pitched battle.[28] Gannys commanded at least two full legions and held numerical superiority over the fewer levies that Macrinus had been able to raise. Macrinus had ordered the Praetorian Guard to set aside their scaled armour breastplates and grooved shields in favour of lighter oval shields prior to the battle. This made them lighter and more manoeuvrable and negated any advantage light Parthian lancers had.[29][30] The Praetorian Guards broke through the lines of Gannys' force, which turned to flee. During the retreat, however, Julia Maesa and Soaemias, in a surprising act of heroism joined the fray, leaping from their chariots to rally the retreating forces,[31] while Gannys charged on horseback headlong into the enemy. These actions effectively ended the retreat; the troops resumed the assault with renewed morale, turning the tide of battle.[28][32] Fearing defeat, Macrinus fled back to the city of Antioch,[24] attempting escape before being executed in Cappadocia,[33][34] while his son Diadumenian was captured en route in Zeugma, and executed as well.[35]

Elagablus entered Antioch as its emperor, refraining the soldiers from sacking the city and sending a message to the senate who were forced to accept the young boy as their new emperor.[36] Upon ascension he took up the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus.[37]

Reign of Elagabalus

.jpg)

Although now declared emperor, Elagabalus' claim was not uncontested, however, as several others laid claim to the Roman Throne. These included Verus the commander of Legio III Gallica who ironically was the first to proclaim Elagabalus as emperor, and Gellius Maximus the commander of Legio IV Scythica. These rebellions were quashed and their instigators executed.[36]

Elagabalus spent the winter of 218–219 in Nicomedia before he set off to enter Rome.[38] Maesa allegedly urged him to enter the capital draped in Roman clothes, but instead, he had a painting of him made as a priest making offerings to the Emesene deity El-Gabal.[38] The painting was hung right above the statue of Victoria in the senate, putting senators in the awkward position of having to make offerings to the Syrian deity whenever they wanted to make offerings to Victoria.[39]

Both Maesa and her daughter Soaemias are featured heavily in all literary accounts of his reign, and are credited with much influence over the young emperor.[40] Julia Maesa was honored with the titles of 'Augusta, mater castrorum et senatus' (empress, mother of the camp and the senate) and 'avia Augusti' (grandmother of the emperor).[40]

Soon, the young emperor was no longer popular with the praetorians, who did not approve of his revolting behavior and his odd religious rituals,[41] and considering how their support was crucial for his rule to survive, this was an extremely dangerous development.[41] Julia Maesa decided to take measures to prevent things from getting too out of hand.[41] She convinced her grandson to adopt his cousin, her grandson Alexander, and declare him caesar, with the argument that it would leave more time for Elagabalus to devote himself to religious matters.[41] The adoption of the 12 years old Alexander provided a strategic shift for the supporters of Elagablus,[41] as some of the supporters felt it was no longer wise to tie their fate with that of the priest-emperor and saw an alternative in his adopted son.[41][42]

Whatsoever, rivalry was soon increasing between the two boys and Elagabalus regretted adopting his more-popular cousin.[43] The soldiers began to look more favorably upon Elagabalus' cousin, and the allies and supporters of the dynasty as well as the imperial family itself became divided,[43] with Elagabalus and Soaemias on one side, and Mamaea, Maesa and Alexander on the other.[44]

By the beginning of 222, Alexander and Elagabalus became so estranged with each other that they no longer appeared together in public.[44] An assassination attempt against Alexander by Elagabalus enraged the praetorian guards who demanded an assurance for Alexander's safety from Elagabalus and the dismissal of some certain officials.[44] Elagablus broke his promise, prompting the praetorian guard to slay Elagabalus and his mother, cutting their heads off and throwing aside their bodies.[44] Alexander was now proclaimed emperor.[44]

A traditionally held belief is that while the new emperor was mainly involved in religious matters, Julia Maesa and her daughter were the ones effectively running the state.[40] This claim has been treated with caution by contemporary historians such as Barabara Levick, as in ancient Rome, politics and religion were intertwined together and the rule of Elagabalus and the supremacy of his deity broke this relationship.[45] In any case it's certain that Maesa had influence over the young boy, but Elagabalus' disagreements and neglect of advice from Maesa, who can be presented as an advocate of Roman traditionalism, has been reported and it may well be the cause of his downfall.[45]

It is probable that Julia Maesa herself was responsible for the assassination of her daughter and grandson.[46] This would certainly have been a painful sacrifice for Maesa to make but a necessary one to protect her family's grip on power and preserve the empire's stability.[46]

Reign of Severus Alexander

Alexander ascended the throne at the age of around 15, and he was kept in check by his mother and grandmother who were determined to erase the negative impression of Elagabalus. He was given the name Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander to emphasize his relationship to Septimius Severus, the founder of the dynasty.[46]

The epigraphical evidence during Severus Alexander's reign attests that the early years of his reign were dominated by his mother and grandmother, as inscriptions carrying the emperor's name referred to him as Juliae Mamaeae Aug(ustae) filio Juliae Maesae Aug(ustae) nepote (the son of Julia Mamaea and grandson of Julia Maesa).[46]

The changes introduced by Maesa and her daughter included selecting a council of sixteen chosen for their moderation and experience to advise the young emperor, and the two Julias tried to restore a moderate and dignified form of government.[47][6] The eastern religious practices introduced by the former emperor were eradicated in Rome and his religious edicts were reversed, the sacred stone of El-Gabal was returned to Emesa and the vast temple which had been dedicated to him by Elagabalus was rededicated to Jupiter.[46]

Death

Maesa likely died between November 224 and 227.[48][6] Her death deprived her daughter, Julia Mamaea, not only of a mother but also of a political mentor and colleague, and Julia Mamaea was now alone in charge of the imperial government.[6]

Deification

Like her sister Julia Domna before her was,[49] Julia Maesa was deified.[7] In the Feriale Duranum, the list of religious observances of the Cohors XX Palmyrenorum, dating to c. 227 AD,[48] Maesa is made a supplication on her birthday which is the 7th of May.[7] Coins commemorating her deification show her borne aloft on the back of a peacock. Unfortunately the coins are undated, but she also appears deified on the Acta Fratrum Arvalium of 7 November in 224, which lists the number of gods and goddesses the Arval Brethren made sacrifices to on that certain date.[48]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Julia Maesa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Salisbury 2001, p. 183.

- Birley 2002, p. 222.

- Grant 1996, p. 47.

- Burns 2006, p. 207.

- Burns 2006, p. 209.

- Burns 2006, p. 217.

- Lee 2016, p. 16.

- "The Severan Dynasty (193–235 A.D.)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2000. Archived from the original on 2019-05-03. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- Birley 2002, p. 72.

- Levick 2007, p. 23.

- Shahid 1984, p. 33.

- Shahid 1984, p. 41.

- Levick 2007, p. 3.

- Kean 2005, p. 120.

- Icks 2011, p. 56.

- Lightman & Lightman 2008, p. 171.

- Icks 2011, p. 58.

- Birley 2002, p. 192.

- Bunson 2014, p. 193.

- Icks 2011, p. 11.

- Halsberghe 1972, p. 60.

- Gibbon 1961, p. 183.

- Mennen 2011, p. 165.

- Downey 1961, pp. 249–250.

- Dio 1927, p. 417.

- Dio 1927, 79.34.3.

- Dio 1927, 79.34.4.

- Gibbon 1961, p. 184.

- Dio 1927, p. 425.

- Dio 1927, 79.37.4.

- Lightman & Lightman 2008, p. 172.

- Goldsworthy 2009, pp. 78–79.

- Crevier 1814, p. 237.

- Bell 1834, p. 229.

- Vagi 2000, p. 290.

- Icks 2011, p. 14.

- Icks 2011, p. 55.

- Icks 2011, p. 17.

- Heliogabalus (2) – Livius

- Icks 2011, p. 19.

- Icks 2011, p. 37.

- Icks 2011, p. 38.

- Icks 2011, p. 39.

- Burns 2006, p. 214.

- Levick 2007, p. 149.

- Burns 2006, p. 215.

- Burns 2006, p. 216.

- McHugh 2017, p. 181.

- Levick 2007, p. 145.

Bibliography

- Bell, Robert (1834). Volume 2 of A History of Rome. Cabinet Cyclopaedia. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman. OCLC 499310353.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Birley, Anthony R (2002). Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134707461.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunson, Matthew (2014). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438110271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, Jasper (2006). Great Women of Imperial Rome: Mothers and Wives of the Caesars. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134131853.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crevier, Jean Baptiste Louis (1814). The History of the Roman Emperors From Augustus to Constantine, Volume 8. F. C. & J. Rivington. OCLC 2942662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dio, Cassius (1927) [1927]. Roman History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674991965.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Downey, Glanville (1961) [1961]. History of Antioch in Syria: From Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Literary Licensing. ISBN 1-258-48665-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbon, Edward (1961). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 1. Claxton, Remsen, & Haffelfinger. OCLC 3584351.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415127721.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halsberghe, Gaston H. (1972). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-29625-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Icks, Martijn (2011). The Crimes of Elegabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-362-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kean, Roger Michael (2005). The complete chronicle of the emperors of Rome. Thalamus. ISBN 978-1902886053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, A. D. (2016). Pagans and Christians in Late Antiquity: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317408628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levick, Barbara (2007). Julia Domna: Syrian Empress. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134323517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lightman, Marjorie; Lightman, Benjamin (2008). A to Z of Ancient Greek and Roman Women. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438107943.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McHugh, John S (2017). Emperor Alexander Severus: Rome's Age of Insurrection, AD222-235. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1473845824.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193–284. Impact of Empire. Volume 12. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9004203594. OCLC 859895124.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (2001). Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576070925.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahid, Irfan (1984). Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantium and the Arabs. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0884021155.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vagi, David L. (2000). Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, c. 82 B.C.–A.D. 480. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 9781579583163.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)