Jess Willard

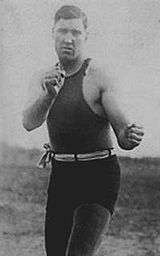

Jess Myron Willard (December 29, 1881 – December 15, 1968) was an American world heavyweight boxing champion known as the Pottawatomie Giant[2][3] who knocked out Jack Johnson in April 1915 for the heavyweight title. He was known for his great strength and size for the time, although today he is also known for his controversial title loss to Jack Dempsey.

| Jess Willard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Statistics | |

| Real name | Jess Myron Willard |

| Nickname(s) | Great White Hope[1] Pottawatomie Giant[2] |

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight |

| Height | 6 ft 6 1⁄2 in (199 cm) |

| Nationality | American |

| Born | December 29, 1881 Pottawatomie County, Kansas |

| Died | December 15, 1968 (aged 86) Los Angeles, California |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 34 |

| Wins | 26 |

| Wins by KO | 20 |

| Losses | 7 |

| Draws | 2 |

| No contests | 0 |

Willard held the championship for more than four years. Today his reign is considered the 11th longest in the heavyweight division. He lost the title to Dempsey in 1919 in one of the most severe beatings ever in a championship bout. Willard was knocked down for the first time in his career during the first round and another seven times before the round was over; some reports claim that he suffered broken ribs, shattered jaw, broken nose, four missing teeth, partial hearing loss in one ear along with numerous cuts and contusions,[4] but these reports are highly disputable. Willard fought for two more rounds before retiring on his stool because of the injuries he received in the first round, relinquishing the title.

At 6 ft 6 1⁄2 in (1.99 m) and 235 lb (107 kg), Willard was the tallest and the largest heavyweight champion in boxing history (and currently the largest of any American heavyweight). He lost that title on June 29, 1933 to the Italian Primo Carnera, at 6 ft 5 1⁄2 in (197 cm) and 275 pounds (125 kg). Then in 2004, the Ukrainian Vitali Klitschko won the WBC title at 6 ft 7 in (201 cm). And finally the 7 ft Russian Nikolai Valuev won the WBA title in 2005 and remains the largest heavyweight champion today.

Early life

Jess Myron Willard was born on 29 December 1881 at Saint Clere, Kansas. In his teenage years and twenties he worked as a cowboy.[2] He was of mostly English ancestry, which had been in North America since the colonial era. The first member of the Willard family arrived in Virginia in the 1630s.[5]

Boxing career

Willard first began boxing at the age of 27. Despite his late start, he proved successful, defeating top-ranked opponents to earn a chance to fight for the Championship. He said he started boxing because he did not have much of an education, but thought his size and strength could earn him a good living. He was a gentle and friendly person and did not enjoy boxing or hurting people, so often waited until his opponent attacked him before punching back, which made him feel at ease as if he were defending himself. He was often maligned as an uncoordinated oaf rather than a skilled boxer, but his counter-punching style, coupled with his enormous strength and stamina, proved successful against top fighters. His physical strength was so great that he was reputed to be able to kill a man with a single punch, which unfortunately proved to be a fact during his fight with Jack "Bull" Young in 1913, who was punched in the head and killed in the 9th round. Willard was charged with second-degree murder, but was successfully defended by lawyer Earl Rogers.

Jack Johnson fight

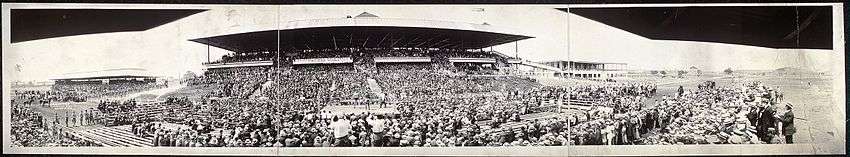

On April 5, 1915, in front of a huge crowd at the new Oriental Park Racetrack in Havana, Cuba, he knocked out champion Jack Johnson in the 26th round to win the world heavyweight boxing championship. Johnson later claimed to have intentionally lost the fight, despite the fact there is evidence of Willard winning fairly, which can be seen clearly in the recorded footage, as well as the comments Johnson made to his cornermen between rounds and immediately after the fight, and that he bet $2500 on himself to win.[6][7][8] Willard said, "If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he'd done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there." Johnson later acknowledged lying about the throwing the fight after footage of the fight was made widely available in the United States. Shortly after the fight Jack Johnson had actually accepted defeat gracefully saying "Willard was too much for me, I just didn't have it."[9]

Johnson found that he could not knock out the giant Willard, who fought as a counterpuncher, making Johnson do all the leading. Johnson began to tire after the 20th round, and was visibly hurt by heavy body punches from Willard in rounds preceding the 26th-round knockout. Johnson's claim of a "dive" gained momentum because most fans only saw a still photo of Johnson lying on the canvas shading his eyes from the broiling Cuban sun. No films of the fight were allowed to be shown in the United States because of an inter-state ban on the trafficking of fight films that was in effect at the time. Most boxing fans only saw the film of the Johnson-Willard fight when a copy was found in 1967.

Willard fought several times over the next four years, but made only one official title defense prior to 1919, defeating Frank Moran on March 25, 1916, at Madison Square Garden.

Jack Dempsey fight

At age 37, Willard lost his title to Dempsey on July 4, 1919, in Toledo. Dempsey knocked Willard down for the first time in his career with a left hook in the first round. Dempsey knocked Willard down seven times in the first round—although it should be remembered that rules at the time permitted standing almost over a knocked-down opponent and hitting him again as soon as both knees had left the canvas. Dempsey won the title when Willard was unable to continue after the third round. In the fight, Willard was later reputed to have suffered a broken jaw, cheekbone, and ribs, as well as losing several teeth. His attempt to fight to the finish, ending when he was unable to come out for the fourth round, is considered one of the most courageous performances in boxing history. However, the extent of Willard's injuries have been highly disputed, since contemporary reports show that only a few days after the fight, there were few traces of any damage other than a couple of bruises:

- A statement was issued after the fight by Jim Byrne, "official physician to a local athletic club in Toledo", that Willard had a dislocated jaw, a fractured cheek bone and several "mashed" ribs and that it would be "at least six weeks before Willard is back to normal condition and can move comfortably." This was reported in the Kansas City Times, July 8, 1919, p. 10 "Willard's Jaw Dislocated.”

- Pacheco and other reporters based the extent of Willard’s injuries on this widely distributed report by Byrne who was not a physician. However it soon turned out that Jim Byrne was not a doctor, but was rather a "rubber" in a bathhouse in Battle Creek, Michigan. According to the reporter in an article, "Willard's Jaw is All Right," Kansas City Star, July 8, 1919, p.11, Byrne "doesn't know a nickel's worth about the human anatomy."

- Other reports also make it clear that Willard was not as severely injured as has been claimed. An interview by a reporter from Kansas City on July 5, 1919, "Jess Refuses to Alibi," Kansas City Star, July 6, 1919, p. 14, the day after the fight, showed that "aside from the swelling on the right side of his face, which is under cold applications, he was none the worse apparently for his encounter with Dempsey."

- In an interview on July 7, the Kansas City Times announced that Jess and his wife were leaving Toledo and driving their car back to Lawrence, Kansas that day. His condition seemed to be fine. "The swelling over his left eye had entirely disappeared and the only mark he bore was a slight discoloration over the eye and a cut lip." ("Willard starts for Home," Kansas City Times, July 8, 1919, p.10).

- Another reporter interviewed Jess in Chicago on his way home. "Hello, Jess" said the reporter, "How do you feel ?" "Hello," said Willard, "I'm feeling great. Would you like to spar a few rounds?" (Kansas City Star, July 10, 1919, p. 10).

- Later, according to a reporter for the Topeka Daily Capital, July 16, 1919, p. 8, who interviewed Jess when he got back to Lawrence, "The ex-champion didn't have any black eye, nor any signs that he was injured in any way."[10]

Contemporaries also reported that Willard had lost no teeth, and that his jaw was not broken. A day after the fight, the New York Times interviewed Willard at length, and speaking would have been very hard if his jaw really had been multiply fractured. Willard said:

- Dempsey is a remarkable hitter. It was the first time that I had ever been knocked off my feet. I have sent many birds home in the same bruised condition that I am in, and now I know how they felt. I sincerely wish Dempsey all the luck possible and hope that he garnishes all the riches that comes with the championship. I have had my fling with the title. I was champion for four years and I assure you that they'll never have to give a benefit for me. I have invested the money I have made.

- Plaster of Paris theory

Shortly after the fight rumors of foul play from Dempsey's corner began to spread. The rumours appeared to be confirmed years later when the January 13, 1964 issue of Sport's Illustrated contained an article titled "He didn't know the gloves were loaded" in which Dempsey's manager, Jack Kearns, confessed to loading Dempsey's gloves with plaster of Paris disguised as talcum powder, without Dempsey's knowledge. Kearns claimed he had bet $10,000 at 10-1 odds that Dempsey would win in the first round and couldn't afford to lose.[10] However, this story has been disputed. Nat Fleischer, later founder of The Ring Magazine, was there when Dempsey's hands were wrapped: "Jack Dempsey had no loaded gloves, and no plaster of Paris over his bandages. I watched the proceedings, and the only person who had anything to do with the taping of Jack's hands was Deforest. Kearns had nothing to do with it, so his plaster of Paris story is simply not true. Deforest himself said that he regarded the stories of Dempsey's gloves being loaded as libel, calling them 'trash' and said he did not apply any foreign substance to them, which I can verify since I watched the taping."[11] Historian J. J. Johnston ended all discussion on that subject when he pointed out that "the films show Willard upon entering the ring walking over to Dempsey and examining his hands. That should end any possibility of plaster of Paris or any other substance on his hands." And if the extent of Willard's injuries was exaggerated, as contemporary sources indicate, there is nothing to explain about Dempsey's hands. Furthermore, tests performed by Cleveland Williams, Hugh Benbow and Perry Payne (William's manager and trainer) for the magazine Boxing Illustrated proved that the plaster of Paris would have crumbled in the intense heat experienced on the day of the fight, rendering it useless for the purpose of inflicting damage or pain on Willard.[10]

- Concealed metal object theory

When interviewed by Harry Carpenter of the BBC Sport in the 1960s at his house in California, Willard said to the reporter, "I'll show you, how I was beaten." He then drew a metal bolt from a cardbox, saying that Dempsey held the bolt in his hand, not within the glove but at the palm of it, attached to the thumb sideways, and used the bolt rather for cutting-and-slicing-like moves to inflict blood-spilling cuts and pain, relinquishing it just as the bout was stopped, and according to Willard, the bolt was found on the floor of the ring at the end of the fight and he kept it. Mike Tyson, who studied the case in-depth and very thoroughly, later joined Carpenter to discuss the subject. Tyson, a great admirer of Dempsey, admitted that "he just did whatever Jack Kearns told him to do," and "in those days anything could have happened" for that there was no agency or other legal authority at the time, which was officially empowered to oversee and protect fighters from violations of such kind.[12]

Comeback

After losing his title fight with Dempsey, Willard went into semiretirement from the ring, fighting only exhibition bouts for the next four years.[2] On May 12, 1923, promoter Tex Rickard arranged for Willard to make a comeback, fighting Floyd Johnson as part of the first line-up of boxing matches at the newly opened Yankee Stadium in New York City.[13] 63,000 spectators attended the match, which the 41-year-old Willard was widely expected to lose.[13] However, after Willard took a beating for several rounds, he came back to knock down Johnson in the 9th and 11th rounds, and Willard earned a TKO victory. Damon Runyon wrote afterward: "Youth, take off your hat and bow low and respectfully to Age. For days and days, the sole topic of conversation in the world of sport will be Willard's astonishing comeback."[13]

Willard followed up this victory by facing contender Luis Ángel Firpo on July 12, 1923.[13] The fight was held at Boyle's Thirty Acres in New Jersey, in front of more than 75,000 spectators. Willard was knocked out in the eighth round, and then permanently retired from boxing.

Later years

_-_Ad_4.jpg)

Willard parlayed his boxing fame into an acting career of a sort. He acted in a vaudeville show, had a role in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, and starred in a 1919 feature film The Challenge of Chance.[14] In 1933, he appeared in a bit part in a boxing movie, The Prizefighter and the Lady, with Max Baer and Myrna Loy.[14]

Death

Willard died on 15 December 1968, in Los Angeles, California, from congestive heart failure. He had been admitted to a hospital a week earlier for a heart condition, but left against a doctor's advice. He returned again after suffering a stroke and died 12 hours later.[15]

Having died at age 86, Willard was the longest-lived heavyweight champion in history until he was surpassed by his old foe Jack Dempsey (who died in 1983, aged 87), and then by Max Schmeling (who died in 2005 at the age of 99, making him the longest-lived heavyweight champion in boxing history).

Willard's body was buried at Forest Lawn, Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles.[16]

Tributes

In 2003 he was inducted posthumously into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.[3]

Cultural references

Willard and a dispute he had with Harry Houdini is the topic of Andy Duncan's Nebula Award nominated novella "The Pottawatomie Giant."[17] In 2020, a television program Antiques Roadshow - Crocker Art Museum (Season 24, Episode 8, Part 2), showed a photograph from his 5 April 1915 championship winning match, and the commemorative pocket watch Willard carried which was estimated to be valued between $15,000 and $50,000.

Professional boxing record

| 34 fights | 25 wins | 7 losses |

| By knockout | 20 | 3 |

| By decision | 5 | 3 |

| By disqualification | 0 | 1 |

| Draws | 2 | |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | Loss | 26–6–2 | KO | 8 (12), 1:55 | 12 Jul 1923 | |||

| 33 | Win | 25–6–2 | TKO | 11 (15) | 12 May 1923 | |||

| 32 | Loss | 24–6–2 | RTD | 3 (12) | 4 Jul 1919 | Lost lineal heavyweight title | ||

| 31 | Win | 23–6–2 | NWS | 10 | 25 Mar 1916 | Retained lineal heavyweight title | ||

| 30 | Win | 22–6–2 | KO | 26 (45), 1:26 | 5 Apr 1915 | Won lineal heavyweight title | ||

| 29 | Win | 21–6–2 | KO | 6 (10) | 28 Apr 1914 | |||

| 28 | Win | 20–6–2 | KO | 9 (10) | 13 Apr 1914 | |||

| 27 | Loss | 19–6–2 | NWS | 12 | 27 Mar 1914 | |||

| 26 | Win | 19–5–2 | KO | 9 (20) | 29 Dec 1913 | |||

| 25 | Win | 18–5–2 | KO | 2 (10) | 12 Dec 1913 | |||

| 24 | Win | 17–5–2 | NWS | 10 | 3 Dec 1913 | |||

| 23 | Win | 16–5–2 | TKO | 2 (10) | 24 Nov 1913 | |||

| 22 | Loss | 15–5–2 | NWS | 10 | 17 Nov 1913 | |||

| 21 | Win | 15–4–2 | KO | 11 (20) | 22 Aug 1913 | |||

| 20 | Win | 14–4–2 | TKO | 8 (10) | 4 Jul 1913 | |||

| 19 | Draw | 13–4–2 | PTS | 4 | 27 Jun 1913 | |||

| 18 | Loss | 13–4–1 | PTS | 20 | 20 May 1913 | |||

| 17 | Win | 13–3–1 | KO | 4 (10) | 5 Mar 1913 | |||

| 16 | Win | 12–3–1 | TKO | 5 (10), 1:50 | 22 Jan 1913 | |||

| 15 | Win | 11–3–1 | KO | 8 (10) | 27 Dec 1912 | |||

| 14 | Win | 10–3–1 | KO | 1 (10) | 2 Dec 1912 | |||

| 13 | Draw | 9–3–1 | NWS | 10 | 19 Aug 1912 | |||

| 12 | Win | 9–3 | NWS | 10 | 29 Jul 1912 | |||

| 11 | Win | 8–3 | KO | 5 | 2 Jul 1912 | |||

| 10 | Win | 7–3 | TKO | 3 (6) | 29 May 1912 | |||

| 9 | Win | 6–3 | KO | 6 (10) | 22 May 1912 | |||

| 8 | Loss | 5–3 | TKO | 5 (10) | 9 Oct 1911 | |||

| 7 | Win | 5–2 | PTS | 10 | 10 Aug 1911 | |||

| 6 | Win | 4–2 | PTS | 10 | 4 Jul 1911 | |||

| 5 | Win | 3–2 | KO | 4 (15) | 15 May 1911 | |||

| 4 | Win | 3–1 | PTS | 4 (10) | 14 Apr 1911 | |||

| 3 | Win | 2–1 | KO | 3 (15), 1:13 | 24 Mar 1911 | |||

| 2 | Win | 1–1 | KO | 3 (10) | 7 Mar 1911 | |||

| 1 | Loss | 0–1 | DQ | 10 (15), 0:45 | 15 Feb 1911 |

See also

- List of heavyweight boxing champions

References

- "'Great White Hope' Jess Willard Succumbs". Ocala Star-Banner. December 16, 1968. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- "Jess Willard Biography". cyberboxingzone.com. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- "HOF Website". International Boxing Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- Archived January 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Life Story of Heavyweight Champion Jess Willard by Jim Mace

- Sports in the Western World By William Joseph Baker

- Tex Rickard: Boxing's Greatest Promoter By Colleen Aycock, Mark Scott pag 115

- Fleischer, Nat, 50 Years At Ringside (Fleet Publishing Corporation, 1958), pp. 88-89.

- The Great White Hopes: The Quest to Defeat Jack Johnson By Graeme Kent

- Cox, Monte D.; Bardelli, John A.; Caico, Bob; Cox, Jeff; Cuoc, Dan; Johnston, Chuck; Moyle, Clay; Stallone, Frank; Ugarkovich, Miles (December 1, 2004). "Were Dempsey's Gloves Loaded? You Decide!". Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Fleischer, Nat, 50 Years At Ringside, p. 118.

- Mike Tyson presents - The Heavyweights (Documentary, 1988).

- "Willard Helped Raise the Roof at Yankee Stadium". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- "Jess Willard IMDB Entry". IMDB. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1898&dat=19681216&id=BwhJAAAAIBAJ&sjid=awUNAAAAIBAJ&pg=3826,4605907&hl=en

- Entry for Willard's grave in Findagrave website (2019). https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/1107/jess-myron-willard

- Duncan, Andy (2012). The Pottawatomie Giant and Other Stories. Hornsea, UK: PS Publishing. p. 308. ISBN 9781848633094.

Further reading

- Allen, Arly (2017). Jess Willard: Heavyweight Champion of the World (1915-1919). McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC. ISBN 9781476664446.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jess Willard. |

- Boxing record for Jess Willard from BoxRec

- Jess Willard's Boxing Gear at Kansas Museum of History

- Willard v. Dempsey on YouTube

- Jess Willard - CBZ Profile

- Boxing Hall of Fame

- ESPN.com

| Achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jack Johnson |

World Heavyweight Champion April 5, 1915 – July 4, 1919 |

Succeeded by Jack Dempsey |

| Tallest Heavyweight Champion April 5, 1915 – April 24, 2004 |

Succeeded by Vitali Klitschko | |

| Oldest Heavyweight Champion January 4, 1919 – July 18, 1951 |

Succeeded by Jersey Joe Walcott | |

| Preceded by Tommy Burns |

Oldest Living Heavyweight Champion May 10, 1955 – December 15, 1968 |

Succeeded by Jack Dempsey |

| Preceded by James J. Jeffries |

Longest Living Heavyweight Champion November 18, 1959 – June 11, 1982 | |