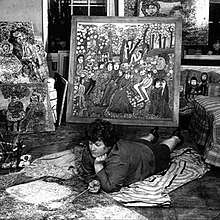

Janet Sobel

Janet Sobel (May 31, 1893 – 1968) was a Ukrainian-American Abstract Expressionist whose career started mid-life, at age 45 . Even with an artistic career as brief as hers, Sobel is the first artist to use the drip painting technique which directly influenced Jackson Pollock.[1]

Janet Sobel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jennie Olechovsky May 31, 1893 Ukraine |

| Died | 1968 (aged 73–74) |

| Nationality | Ukrainian, American |

| Education | No formal artistic education |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Pro and Contra (1941), Through the Glass (1944), Milky Way (1945) |

| Movement | Abstract Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | Max Sobel |

Early life

Janet Sobel was born as Jennie Olechovsky in 1893 in Ukraine. Her father, Baruch Olechovsky,[2] was killed in a Russian pogrom. Sobel along with her mother, Fannie Kinchuk, and siblings moved to Ellis Island in New York City in 1908.[2] At 17, she married Max Sobel and was a mother of five when she began painting in 1937. Sobel became a known suburban artist housewife that inspired the feminist conversation around domestic roles of women. She produced both non-objective abstractions and figurative artwork.[3] Upon recognizing Sobel's talent, her son helped her artistic development and shared her work with émigré surrealists, Max Ernst, André Breton, as well as John Dewey and Sidney Janis.[4]

Career

Understanding Sobel's Career:

Professionally, Sobel was, primarily, a housewife. [3] Clement Greenberg, an art authority in Sobel's time, wrote on avant-garde painting and positioned "Sobel as a forerunner of Abstract Impressionism", but he made sure to emphasize Sobel's work as inferior to Pollocks by reducing it as "'primitive'" and that of a "'housewife'".[3] Generally, Sobel's work was framed by Greenberg only relative to Abstract Expressionism or to Pollock, and he did not address her during the three years her works circulated in New York galleries until framing Pollock's career.[3] The result is a failure of recognition during her career. But, Peggy Guggenheim did include Sobel's work in her The Art of This Century Gallery in 1945.

As described, some of her work is related to the so-called "drip paintings" of Jackson Pollock, who "'admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him'".[3][4] The critic Clement Greenberg, with Jackson Pollock, saw Sobel's work there in 1946,[5] and in his essay "'American-Type' Painting" cited those works as the first instance of all-over painting he had seen, but this style is attributed to appropriated female nature rather than to artistic creativity; her art evolved from recognizable figures to a more abstract style of paint dripping.[6]

Returning to Pollock: one might see how, in his tacit assumption of the position of the woman—the decentered and the voiceless, the one who flows uncontrollably, the one who figures the void and the unconscious—he remained on some level, a man using his masculine authority to appropriate a feminine space. In fact, one woman had tried to articulate that space before Pollock did, in a similar way—not Krasner but Janet Sobel, who made poured, all-over compositions that unmistakably made an impact on Pollock. Greenberg recalls, Pollock (and I myself) admired [Sobel's] pictures rather furtively" at the Art of This Century gallery in 1944; "The effect—and it was the first really 'all-over' one that I had ever seen ... —was strangely pleasing. Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him. When Sobel is mentioned at all in accounts of Pollock's development, however, she is generally described and so discredited as a "housewife," or amateur, a stratagem that preserves Pollock's status as the unique progenitor, both mother and father of his art, a figure overflowing not only with semen but with amniotic fluid.[7]

"Sobel was part folk artist, Surrealist, and Abstract Expressionist, but critics found it easiest to call her a 'primitive.'"[3] As Zalman summarizes, her title of "primitive" was "a category that enabled her acceptance by the art world but restricted her artistic development."[3] Part of her grouping as a 'primitive' painter was part of a greater movement to try to form a unique American form of art, distinct from European art, while still trying to maintain a hierarchy of 'us and them'. Sobel was grouped as inferior due to her status as a housewife, while other painters could've been dismissed as being mentally inferior in some way.[3] In a way, Sobel also serves as a representative of this conflict.

Inspirations and Influences in her Work:

Her belief in the ethics of self-realization in a democracy led to her encounter with philosopher John Dewey. Dewey championed Sobel by writing about her in a catalogue statement at the Puma Gallery in New York in 1944. In this catalogue he states:

Her work is extraordinarily free from inventiveness and from self-consciousness and pretense. One can believe that to an unusual degree her forms and colors well up from a subconsciousness that is richly stored with sensitive impressions received directly from contact with nature, impressions which have been reorganized in figures in which color and form are happily wed[8]

Sobel used music for inspiration and stimulation of her feelings into her canvas. Sobel's works exemplify the tendency to fill up every empty space, often known as horror vacui. She often depicted her feelings through past experiences. Her depiction of soldiers with cannons and imperial armies, as well as traditional jewish families, reflected the experiences of her childhood. Her figures often demonstrated the time of the Holocaust, where she relived the trauma of her youth. Through her traumas and troubling youth, Sobel found a safe realm for her imagination and anguish through art.[9]

Notable Works

Sobel's initial works show a flair for a primitivist figuration reminiscent of early Chagall and serves to herald early Dubuffet. The abundant floral motifs recall Ukrainian peasant art.

In addition, the need to exploit media of all sorts is very evident (including sand). If her drips paintings weren't vivid enough, she would opt to outline them in ink in order to compensate.

Aiding in inventing Abstract Expressionism did not conclude her imagistic work. Her main goal was visual intensity, which she attained with impressive regularity.

Milky Way, created in 1945, is currently displayed in the Museum of Modern Art.[10]

References

- https://monoskop.org/images/c/ce/Greenberg_Clement_1955_1961_American-Type_Painting.pdf p. 218}

- "Will the Real Janet Sobel Please Stand Up?". www.janetsobel.com. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- Zalman, Sandra (2015). "Janet Sobel: Primitive Modern and the Origins of Abstract Expressionism". Woman's Art Journal. 36 (2): 20–29. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 26430653.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-03-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bob Duggan. "Mother of Invention". Big Think.

- Pollock, Jackson (1999). Jackson Pollock. ISBN 9780870700378.

- Pollock, Jackson (1999). Jackson Pollock. ISBN 9780870700378.

- John Dewey, Janet Sobel, Puma gallery, leaflet catalogue, New York, April 24 to May 14, 1944.

- Levin, Gail (2003). Inside Out: Selected Works by Janet Sobel. New York: Gary Snyder Fine Art. pp. 5 and 6.

- "Janet Sobel. Milky Way. 1945 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

External links

- Grandmother of Drip Painting

- Janet Sobel on artnet

- Hollis Taggart Galleries

- Gary Snyder/Project Space on Janet Sobel

- Will the Real Janet Sobel Please Stand Up? (PDF by Libby Seaberg available for download

- ART IN REVIEW By Roberta Smith The New York Times — PDF available for download)

- Mother of Invention (blog)

- Significant Careers of Determined Artists: Janet Sobel; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

- Images of paintings (Pinterest compilation)