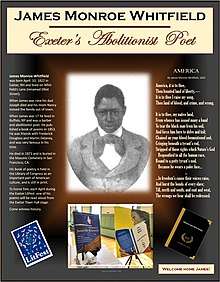

James Monroe Whitfield

James Monroe Whitfield (c. April 10, 1822 – April 23, 1871) was an African-American poet, abolitionist, and political activist. He was a notable writer and activist in abolitionism and African emigration during the antebellum era. He published the book "America and other poems" in 1853, which is still in print.[1]

Early life

Whitfield was born April 10 or 12, 1822, in Exeter, New Hampshire, to Nancy (Paul) of Exeter and Joseph Whitfield, who escaped enslavement in Virginia.[2] His mother Nancy was the daughter of Caesar Nero Paul, a boy of African descent who was enslaved at the age of fourteen as a house-boy in the Maj. John Gilman House, and later became free in 1771 after capture in the French and Indian Wars.[3] Through his mother, James was the nephew of Rev. Thomas Paul of the African Meeting House in Boston, and Jude Hall, veteran of the Revolutionary War.[4] The small family home was on Whitfield's Lane, renamed Elliot Street in 1845. The house on the idyllic tree-lined lane is described in the memoirs of Elizabeth Dow Leonard: "Near the bridge, lived our friend Whitfield in a pretty cottage surrounded by hollyhocks, bachelor's buttons, poppies, saffron, and caraway, and the leafy orchards of their more wealthy neighbors."[5]

James Whitfield attended Exeter schools until the age of nine, when his father died suddenly.[3] His mother Nancy had died when James was seven, so James and his siblings were moved out of town, possibly by his sister.[6] The next records find him in 1839 living in Buffalo, New York, as a barber,[7] at 30 East Seneca St. He owned the shop as well as his home on South Division St. [8] Besides running the barber shop, Whitfield would write in his free time, publishing his own papers by the age of 16.[9]

Whitfield married Frances ((Lewey) b. CT in 1822) on July 12,1843 in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. They had three sons: James Lewey Jr. (b. 1844 in Cleveland), Charles Henry (b. 1846 in Buffalo), and Walter B. (b. 1849 in Buffalo).

His grand-niece was Boston writer and playwright Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins. In her fiction novel of 1900, Contending Forces, she describes a scene at James' home in Exeter with his mother. A 2008 book by Lois Brown goes into detail.[10]

Poetry and writing

Whitfield published a small volume of poetry in 1853 entitled "America and other poems" (publisher James S. Leavitt of Bufffalo) which was dedicated to his friend Martin Delany. Half of the poems are about slavery, the other half about art, nature or people such as John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, or Joseph Cinque.[1] Whitfield found success publishing poems related to abolitionism elsewhere as well, many being printed in The Liberator and The North Star.[9] Whitfield's poems often expressed the oppression affecting African Americans, and moral corruption in politics and religion.[9] One of Whitfield's most famous poems was America, published in 1853 in his poetry book. The poem embodies many of Whitfield's ideas about the hypocrisy of American freedom and democracy, and the difficult lives for both freed and enslaved Africans in the US.[11]

Another of his famous poems, written in 1867 after the Civil War, deals with the topic of the two ships that sailed to the New World in 1620, marking the dual beginnings of America and slavery. It was read before a crowd of two thousand people in San Francisco at a celebration commemorating the fourth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.[12]

Excerpt:

More than two centuries have passed

Since, holding on their stormy way,

Before the furious wintry blast,

Upon a dark December day,

Two sails, with different intent,

Approached the Western Continent.

One vessel bore as rich a freight

As ever yet has crossed the wave;

The living germs to form a State

That knows no master, owns no slave.

She bore the pilgrims to that strand

Which since is rendered classic soil,

Where all the honors of the land

May reach the hardy sons of toil.

The other bore the baleful seeds

Of future fratricidal strife,

The germ of dark and bloody deeds,

Which prey upon a nation's life.

The trafficker in human souls

Had gathered up and chained his prey,

And stood prepared to call the rolls,

When, anchored in Virginia's Bay--

Abolition and emigration movements

In 1850, Frederick Douglass visited Whitfield's barber shop. From their discussion, Douglass became deeply impressed by Whitfield's poetic abilities, calling him in the 1850 Anti-Slavery Bugle a "sable son of genius." Douglass was also impressed by his passion for abolition, commenting that his job as a barber was "painfully disheartening."[13] Although Levine & Ivy, contemporary scholars, contend that the shop was a perfect place to network and exchange ideas.[8]

Beyond abolitionism, Whitfield originally became a prominent member of the Colonization Movement, a popular movement focused on African Americans returning to Africa and indigenous parts of the South or Central Americas.[13] Whitfield broke with Douglass, who was not in favor of emigration and joined with Martin Delany, who favored Haiti or Central America as a location. In August 1853 Delaney, Whitfield and others issued a call for a national convention to address the topic to be held in August 1854 in Cleveland Ohio, which was published in Douglass' North Star. A heated debate between Douglass and Whitfield was published in several issues after that, which helped frame the issue. Whitfield became involved in a proposal by Missouri Senator Frank P. Blair to establish a colony for black colonization in Central America.[7] Later, in 1859, Whitfield was possibly sent out to look for land for the project. [13]

After the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Whitfield dropped the emigration issue and moved to California where he believed there was still opportunity for blacks to flourish without oppressive laws.[8]

Later life

In 1861/62 Whitfield, possibly after his wife died, moved to San Francisco where he was considered by most African-Americans of the Northwest as "the" great African-American poet. [8] His home was at 918 and then 1006 Washington St., and his barber shop at 916 Kearney St., all of which he owned.[8] [14] Whitfield joined the Prince Hall Freemason Hannibal Lodge #1 and later served as a Worshipful Master for their California Grand Lodge 1864-69.[15]

On April 23, 1871, he died of heart disease in San Francisco at the age of 49. Whitfield was interred at the now defunct Masonic Cemetery.[7][16]

Legacy & Honors

"America and other Poems" published in 1853 is held in the Library of Congress.[1]

Whitfield's birth town, Exeter, New Hampshire reads aloud a Whitfield poem at their annual literary festival. [17]

See also

References

- "America and other Poems". Library of Congress. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ""The Works of James M. Whitfield"". Archived from the original on 2018-12-23. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- Dixon, David T., "Freedom Earned, Equality Denied: Evolving Race Relations in Exeter and Vicinity, 1776–1876", Bridge over Troubled Waters.

- Thorenz, Matt, "African Americans at New Windsor: Private Jude Hall, 2nd New Hampshire Regiment", Teaching the Hudson Valley, February 24, 2013.

- Dow Leonard, Elizabeth (1922). A Few Reminisces of my Exeter Life.

- Rimkunas, Barbara. "James Monroe Whitfield: Abolitionist Poet". Exeter Newsletter. Seacoast Online Media. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- "Whitfield, James Monroe (1822–1871) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". BlackPast.org. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- Wilson, Ivy (2011). The Works of James M. Whitfield. UNC Press. p. 205.

- Foundation, Poetry (December 6, 2018). "James Monroe Whitfield". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- Brown, Lois, "Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution", Questia.

- aapone (2008-08-06). "America by James Monroe Whitfield - Poems | Academy of American Poets". America. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- "POEM in honor of the FOURTH ANNIVERSARY of PRESIDENT LINCOLN'S PROCLAMATION OF EMANCIPATION". ClassroomElectric. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Sherman, Joan R. (April 1972). "James Monroe Whitfield, Poet and Emigrationist: A Voice of Protest and Despair". The Journal of Negro History. 57 (2): 169–176. doi:10.2307/2717220. ISSN 0022-2992.

- "Elevator 21 February 1868 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- California Grand Lodge History.

- "Whitfields gravesite". Find a Grave. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Exeter LitFest". exeterlitfest.com. Retrieved 27 December 2019.