James Lenox

James Lenox (August 19, 1800 – February 17, 1880) was an American bibliophile and philanthropist. His collection of paintings and books eventually became known as the Lenox Library and in 1895 became part of the New York Public Library.[1]

James Lenox | |

|---|---|

Photograph taken in the 1870s | |

| Born | August 19, 1800 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 17, 1880 (aged 79) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Columbia College |

| Occupation | Lawyer, philanthropist |

| Parent(s) | Robert Lenox Rachel Carmer Lenox |

| Relatives | David S. Kennedy (cousin) |

| Signature | |

Early life

Lenox was born in New York City on August 19, 1800. He was the only surviving son of six children born to Rachel (née Carmer) Lenox and Robert Lenox (1759–1839).[2][3] His father was a wealthy merchant who was born in Kirkcudbright, Scotland, emigrated to America during the Revolutionary War, and settled in New York in 1783.[4] Of his five sisters, four married and one remained single, like Lenox, throughout her life.[4]

His maternal grandfather was Nicholas Carmer, a New York cabinet maker.[4] Upon his father's death in 1839, Lenox inherited a fortune of over a million dollars and 30 acres of land between Fourth and Fifth Avenues.[4][5] A graduate of Columbia College, he studied law and was admitted to the bar, but never practiced. He retired from business when his father died.[4]

Career

Lenox went to Europe soon after his admission to the bar, and while abroad, began collecting rare books. This, along with collecting art, became the absorbing passion of his life. For half a century, he devoted the greater part of his time and talent to forming a library and gallery of paintings, unsurpassed in value by any other private collection in the New World. In 1870 these, together with many rare manuscripts, marble busts and statues, mosaics, engravings, and curios, became the Lenox Library in New York City.[6] Lenox served as its first president.

The library occupied the crest of the hill on Fifth Avenue, between 70th and 71st Streets, overlooking Central Park. On May 23, 1895, the Lenox Library was consolidated with the Astor Library and the Tilden Trust to form the New York Public Library.[6]

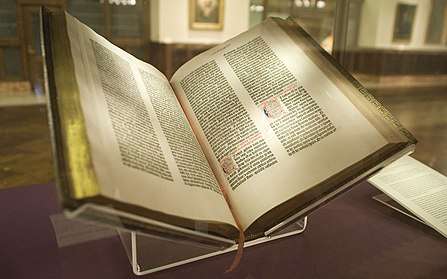

The collection of Bibles, including the Gutenberg Bible—both in number and rarity—were believed to be unequaled even to those of the British Museum; while its Americana, incunabula, and Shakespeariana, surpassed those of any other American library, public or private. The collection was valued at nearly a million dollars, which, with the $900,000 for the land, building, and endowment, made the total above $2,000,000. The Frick Collection stands on the Lenox Library's former site.[6]

Lenox was a founder of the Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. His gifts to it amounted to $600,000. He also made important gifts to Princeton College and Seminary, and gave liberally to numerous churches and charities connected with the Presbyterian Church. Lenox was also the president of the American Bible Society, to which he was a liberal donor. James Grant Wilson reports passing on several anonymous gifts from Lenox to needy men of letters. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1854,[7] and served as the society's vice-president from 1868 to 1880.[8]

Lenox occasionally reprinted limited editions, restricted to ten or twenty copies, of rare books, which he placed in some of the great public libraries and notable private collections, for example that of John Carter Brown. Portraits of Lenox were painted by Francis Grant in 1848, and by G. P. A. Healy three years later. He was also painted by Daniel Huntington in 1874.[9][10]

Personal life

Lenox never married. An early love, the only woman to whom he was romantically attached, refused him and remained unmarried following his death. The broken romance spurred his increasing reclusiveness. He declined proffered visits from the most distinguished men of the day. An eminent scholar, who was occupied for many weeks in consulting rare books not to be found elsewhere, failed to obtain access to Lenox's library. He was assigned an apartment in Lenox's spacious mansion and the works were sent in installments without him ever entering the library or meeting Lenox.[6]

In 1855, there were 19 millionaires in New York. He was the third richest man in New York worth approximately three million dollars.[11]

Lenox died at his home, 53 Fifth Avenue in New York City, on February 17, 1880.[4] He was buried in the New York City Marble Cemetery.[12] Two of his seven sisters outlived him. Henrietta Lenox, the last survivor, gave the Lenox Library 22 valuable adjoining lots and $100,000 for the purchase of books. Lenox Avenue in Harlem is named for James Lenox. In addition to several charities,[13] his estate was left to his relations, including his sister, Henrietta A. Lenox, Mary Lenox Sheafe, another sister, and various nephews and nieces, including Elizabeth S. Maitland, James Lenox Belknap, Robert Lenox Banks, James Lenox Banks, Robert Lenox Kennedy, Rachael Lenox Kennedy, and Mary Lenox Kennedy.[lower-alpha 1] A portion was also left to grand-nieces and grand-nephews including Alexander Maitland, Eliza Lenox Maitland, Robert Lenox Maitland, and Henry Van Rensselaer Kennedy.[17]

References

- Notes

- Lenox's sister, Rachel Carmer Lenox (b. 1792), was married to David Sproat Kennedy (1791–1853).[14] Their son, James Lenox Kennedy (1823–1864), was married to Cornelia Van Rensselaer (1836–1864), a daughter of Henry Bell Van Rensselaer.[15] Their son, Lenox's great-nephew, was Henry Van Rensselaer Kennedy (1863–1912), who married Marian Robbins (1862–1946).[2][16]

- Sources

- "James Lenox | American philanthropist and book collector". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Dinner plates (12)". www.nyhistory.org. New-York Historical Society. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Lenox family papers". archives.nypl.org. New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "DEATH OF JAMES LENOX; THE END OF A PHILANTHROPIC LIFE. THE RECORD OF HIS GENEROUS PUBLIC AND PRIVATE CHARITIES--THE LENOX LIBRARY--A MAN WHO LOVED HIS FELLOWMEN". The New York Times. 19 February 1880. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Miller, Tom (12 August 2013). "Daytonian in Manhattan: The Lost Lenox Mansion -- No. 53 5th Avenue". Daytonian in Manhattan. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Stevens, Henry (1886). Recollections of Mr. James Lenox of New York, & the Formation of His Library. Stevens. p. 3. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- Dunbar, B. (1987). Members and Officers of the American Antiquarian Society. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

-

-

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (2015). The Book of Wealth: A Study of the Achievements of Civilization. Achievements of Civilization. p. 745. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "BURIAL OF JAMES LENOX.; THE SIMPLE TASTES OF THE PHILANTHROPIST RESPECTED AT HIS FUNERAL". The New York Times. 22 February 1880. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "MISCELLANEOUS CITY NEWS; THE WILL OF JAMES LENOX. A PHILANTHROPIC PROVISION MADE FOR THE LIBRARY BEARING HIS NAME". The New York Times. 25 March 1880. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Reynolds, Cuyler (1914). Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Building of a Nation. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 1294. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "DIED" (PDF). The New York Times. December 19, 1864. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- History of the Yale University Class of 1905. Yale University. 1908. p. 229. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "JAMES LENOX'S WILL". The New York Times. 16 March 1880. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Lenox. |