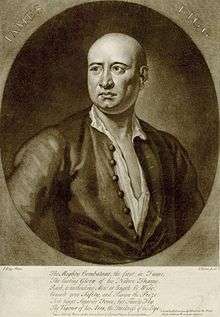

James Figg

James Figg (1684 – 7 December 1734, surname sometimes spelt 'Fig'[2]) exhibited and taught methods of fighting with swords, cudgels and fists from a base in London in the eighteenth century. He is widely recognized as the first English bare-knuckle boxing champion, reigning from 1719 to 1730.

The Mighty Combatant, the first in Fame,

The lasting Glory of his Native Thame,

Rash, & unthinking Men! at length be Wise,

Consult your Safety, and Resign the Prize,

Nor tempt Superior Force; but Timely Fly

The Vigour of his Arm, the Quickness of his Eye.[1]

Life

James Figg was born in Thame in Oxfordshire,[2] "during the reign of William III",[3] and fought his early prize fights there. According to one source, he came to the attention of the Earl of Peterborough, who was a "staunch patron of all brave and manly sports", and who brought him to London.[3] In 1719 he started his own school based at an amphitheatre in Tottenham Court Road, London, where he taught boxing, fencing, and quarterstaff.[2] In 1720, he was fighting at an amphitheatre in Marylebone near the Oxford Road (now called Oxford Street).[4] He also demonstrated his skills at booths and rings set up on parks and fields.

In 1725, the poet John Byrom visited Figg's ampitheatre where, at a cost of 2s 6d, he saw Figg fight Ned Sutton. He reported: "Figg had a wound and bled pretty much; Sutton had a blow with a quarterstaff just upon his knee, which made him lame, so then they gave over".[5]

In June 1727, Sutton had his revenge over Figg, beating him at his own amphitheatre. Figg was forced to withdraw, having suffered a wound in the belly and being "Cloven in the Foot".[6]

On 11 October 1729, it was reported that Figg had been made gate-keeper to Upper St James's Park by the Earl of Essex.[7]

In October 1730, it was reported: "yesterday the invincible Mr. James Figg fought at his Amphitheatre Mr. Holmes, an Irishman, who keeps an Inn at Yaul near Waterford in Ireland, and came into England on purpose to fight this English Champion". It was reported that during the bout, Holmes had his wrist cut to the bone and was therefore forced to retire. It was stated that this fight was the two hundred and seventy-first contest fought by Figg without defeat.[8]

In December 1731, Figg contested a sword-fight with John Sparks before the vising Duke of Lorraine. Foreign ministers and Nobility were also stated to be in the audience for the fighting which took place at the New Theatre, Haymarket.[9][10]

Although records weren't kept as precisely at the time, the common belief is that Figg had a record of 269–1 in 270 fights. His only loss came when Ned Sutton beat him to claim the title. Figg demanded a rematch, which he won, and also went on to retire Sutton in a rubber match. After 1730 he largely gave up fighting, and relied on his three protégés to bring in spectators: Bob Whittaker, Jack Broughton, and George Taylor. Taylor took over Figg's business upon Figg's death in 1734, though Broughton went on to become his most famous protégé.[11]

Figg died on 7 December 1734 and was buried in St Marylebone Parish Churchyard on 12 December of that year.[12]

The Gentleman's Magazine of April 1735, published the following epigram:[13]

Brave Figg is conquer'd, who had conquer'd all,

Yet death can boast but little by his fall,

For, half afraid, he threw a leaden dart,

And maim'd him, e'er he pierc'd his noble heart.

Th' undaunted hero, grimly, as he fell,

Look'd for his arms, and swore by heav'n and hell,

Death never should his conquest have secur'd

Had he fought fairly with a staff or sword.

Legacy

- Captain John Godfrey, who had been trained in sword-fighting by Figg and who later wrote A Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defence, refers to Figg as the "Atlas of the Sword".[14]

- Jack Dempsey called him the father of modern boxing, although this accolade has also been awarded to Jack Broughton. Many of the bouts at the time consisted of boxing, wrestling and fencing with sharp swords. Figg was also a great fencer who engaged in sword duels and singlestick matches.

- Pugilism.org describes Figg as one of the 5 Hardest Men of the Pugilistic Era and founder of the modern sport of boxing.[15]

- Figg was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992.[16]

- In 2010, Figg was inducted in the Bare Knuckle Boxing Hall of Fame.[17]

- A blue plaque dedicated to him was unveiled at The James Figg Pub (formerly The Greyhound Inn), Cornmarket, Thame, on 14 April 2011.[1]

- William Hogarth painted his portrait.

Relationship with William Hogarth

William Hogarth was reputedly a friend and fan. Figg sometimes featured in his pictures, such as Southwark Fair (where he can be seen riding a horse on the far right).[18] It is not unlikely that Hogarth used Figg as model for some of his well known works such as A Rake’s Progress[19] and A Midnight Modern Conversation.[20] But as records in this time are unreliable (Hogarth himself warned against finding likenesses of individuals in his depiction of drunks, stating that "We lash the Vices but the Persons spare")[21] this cannot be ascertained with certainty. A typical example is James Figgs' trade card which was believed to be engraved by Hogarth,[22] but the general consensus is that it was engraved by somebody else, it is even suggested that the trade card itself is a forgery.[23]

In popular culture

James Figg's great-grandson appears as a central character in the Marc Olden novel Poe Must Die and appears alongside other historical figures including Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens. Whilst he is a fictional adaption, Olden's character references the life and experiences of the real Figg.

See also

- List of bare-knuckle boxers

References

- James FIGG (1684–1734). Oxfordshire Blue Plaques

- Miles, Henry Downes (1906). Pugilistica: the history of British boxing containing lives of the most celebrated pugilists. 1. Edinburgh: J. Grant. pp. 8–12.

- Henning, Fred W. J. (1902). Fights for the championship : the men and their times. London: Licensed Victuallers' Gazette. pp. 6–11.

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin; Cunningham, Peter (24 February 2011). London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9781108028073.

- Byrom, John (1854). The Private Journal and Literary Remains of John Byrom: Vol. I, part I. Manchester: Chetham Society. p. 117.

- "The Company at Mr. Figg's". Ipswich Journal. 10 June 1727. p. 3. Retrieved 3 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "London, Oct 2". Newcastle Courant. 11 October 1729. p. 1. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "London October 15". Ipswich Journal. 10 October 1730. p. 4. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "Yesterday a Prize was fought". Caledonian Mercury. 9 December 1731. p. 3. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "London, Dec. 4". Stamford Mercury. 9 December 1731. p. 5. Retrieved 3 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- Derek Birley (1993). Sport and the Making of Britain. Manchester University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-7190-3759-X.

- "London". Derby Mercury. 19 December 1734. p. 4. Retrieved 3 April 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1735). The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume 5. London: Edward Cave. p. 209. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

figg.

- Godfrey, Captain John (1747). A Treatise Upon the Useful Science of Defence: Connecting the Small and Back-sword, and Shewing the Affinity Between Them. London.

- Figg on the Pugilism.org website

- James Figg on the IBHF Website

- "Listing on the website". Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin (1909). Hogarth's London, pictures of the manners of the eighteenth century. New York: E.P. Dutton. p. 432. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- James Figg on BBC Oxford

- A Midnight Modern Conversation (1733) on the website of the Royal Collection Trust

- A Midnight Modern Conversation on the website of the Indianapolis Museum of Art

- James Figgs'trade card on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The trade card on the website of British Museum

External links

- Thame Local History

- James Figg's record at CyberBoxingZone

- James Figg entry at the International Boxing Hall of Fame Website

- Article on James Figg by Iain Abernethy

- Figg article at the England History website

![]()