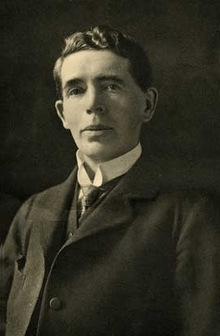

J. B. Bury

John Bagnell Bury, FBA (UK: /ˈbɛrɪ/; 16 October 1861 – 1 June 1927) was an Anglo-Irish[1][2] historian, classical scholar, Medieval Roman historian and philologist. He objected to the label "Byzantinist" explicitly in the preface to the 1889 edition of his Later Roman Empire. He was Erasmus Smith's Professor of Modern History at Trinity College Dublin (1893–1902), before being Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge from 1902 until his death.

J. B. Bury | |

|---|---|

John Bagnell Bury | |

| Born | 16 October 1861 County Monaghan, Ireland |

| Died | 1 June 1927 (aged 65) Rome, Italy |

Early life and education

Bury was born and raised on 16 October 1861 in Clontibret, County Monaghan, as the son of Edward John Bury, where his father was Rector of the Anglican Church of Ireland and Anna Rogers.[3] He was educated first by his parents and then at Foyle College in Derry. He studied classics at Trinity College Dublin, where he was elected a scholar in 1879, and graduated in 1882. He was elected a fellow of Trinity College Dublin in 1885 at the age of 24. In 1893, he was appointed to the Erasmus Smith's Chair of Modern History at Trinity College, which he held for nine years. In 1898 he was appointed Regius Professor of Greek, also at Trinity, a post he held simultaneously with his history professorship.[4] In 1902 he became Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge.

At Cambridge, Bury became mentor to Steven Runciman (the medievalist), who later commented that he had been Bury's "first, and only, student." At first the reclusive Bury tried to brush him off; then, when Runciman mentioned that he could read Russian, Bury gave him a stack of Bulgarian articles to edit, and so their relationship began. Bury was the author of the first truly authoritative biography of Saint Patrick (1905).

Bury remained at Cambridge until his death at the age of 65 in Rome, while on a visit to Italy. He is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

He received the honorary degree Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Glasgow in June 1901,[5] the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Aberdeen in 1905, and the honorary degree Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) from the University of Oxford in October 1902, in connection with the tercentenary of the Bodleian Library.[6]

His brother, Robert Gregg Bury, was an Irish clergyman, classicist, philologist, and a translator of the works of Plato and Sextus Empiricus into English.

Writings

Bury's writings, on subjects ranging from ancient Greece to the 19th-century papacy, are at once scholarly and accessible to the layman. His two works on the philosophy of history elucidated the Victorian ideals of progress and rationality which undergirded his more specific histories. He also led a revival of Byzantine history (which he considered and explicitly called Roman history), which English-speaking historians, following Edward Gibbon, had largely neglected. He contributed to, and was himself the subject of an article in, the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. With Frank Adcock and S. A. Cook he edited The Cambridge Ancient History, launched in 1919.

History as a science

Bury's career shows his evolving thought process and his consideration of the discipline of history as a "science".[7] From his inaugural lecture as Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge in 1902 comes his public proclamation of history as a "science" and not as a branch of "literature". He stated:

I may remind you that history is not a branch of literature. The facts of history, like the facts of geology or astronomy, can supply material for literary art; for manifest reasons they lend themselves to artistic representation far more readily than those of the natural sciences; but to clothe the story of human society in a literary dress is no more the part of a historian as a historian, than it is the part of an astronomer as an astronomer to present in an artistic shape the story of the stars.[8][9]

Bury's lecture continues by defending the claim that history is not literature, which in turns questions the need for a historian's narrative in the discussion of historical facts and essentially evokes the question: is a narrative necessary? But Bury describes his "science" by comparing it to Leopold von Ranke's idea of science and the German phrase that brought Ranke's ideas fame when he exclaimed "tell history as it happened" or "Ich will nur sagen wie es eigentlich gewesen ist." [I only want to say how it actually happened.] Bury's final thoughts during his lecture reiterate his previous statement with a cementing sentence that argues "...she [history] is herself simply a science, no less and no more".[10]

On the argument from ignorance and the burden of proof in his book History of Freedom of Thought he said the following.

Some people speak as if we were not justified in rejecting a theological doctrine unless we can prove it false. But the burden of proof does not lie upon the rejecter.... If you were told that in a certain planet revolving around Sirius there is a race of donkeys who speak the English language and spend their time in discussing eugenics, you could not disprove the statement, but would it, on that account, have any claim to be believed? Some minds would be prepared to accept it, if it were reiterated often enough, through the potent force of suggestion.[11]

Bibliography

Rome

- A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene (2 vols.) (1889)[14][15]

- A History of the Roman Empire From its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius (1893)[16][17]

- A History of the Eastern Roman Empire from the Fall of Irene to the Accession of Basil I (A. D. 802–867) (1912)[18]

- A History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian (1923)[19]

- The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians (1928)[20][21]

- The Life of St. Patrick and His Place in History (1905)[22]

- History of the Papacy in the 19th Century (1864–1878) (1930)

Greece

- A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great (1900)[23]

- The Ancient Greek Historians (Harvard Lectures) (1909)[24]

- The Hellenistic Age: Aspects of Hellenistic Civilization (1923), with E. A. Barber, Edwyn Bevan, and W. W. Tarn[25]

Philosophical

- A History of Freedom of Thought (1913)[26]

- The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into Its Origin and Growth (1920)[27]

As editor

- Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1896–1900) – at Online Library of Liberty

- Edward Augustus Freeman, Freeman's Historical Geography of Europe (third edition, 1903)

- Edward Augustus Freeman, The Atlas To Freeman's Historical Geography (third edition, 1903)

See also

References

- Brian Young, "History", in Mark Bevir, Historicism and the Human Sciences in Victorian Britain, 2017, ISBN 1107166683, p. 181

- Bruce Karl Braswell, A Commentary on Pindar Nemean Nine, 1998, ISBN 3110161249, p. ix

- Hepburn Baynes, Norman (1929). A Bibliography of the Works of J. B. Bury. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 1. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Irish Times, 21 May 2008

- "Glasgow University jubilee". The Times (36481). London. 14 June 1901. p. 10.

- "University intelligence". The Times (36893). London. 8 October 1902. p. 4.

- Goldstein, Doris (October 1977). "J.B. Bury's Philosophy of history: A Reappraisal". The American Historical Review. 82 (4): 896–919. doi:10.1086/ahr/82.4.896. JSTOR 1865117.

-

Bury, John Bagnell (1930). "The science of history". Selected Essays. CUP Archive. p. 9. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

I may remind you that history is not a branch of literature. The facts of history, like the facts of geology or astronomy, can supply material for literary art; for manifest reasons they lend themselves to artistic representation far more readily than those of the natural sciences; but to clothe the story of human society in a literary dress is no more the part of a historian as a historian, than it is the part of an astronomer as an astronomer to present in an artistic shape the story of the stars.

- Stern, Fritz (1972). The Varieties of History: From Voltaire to the Present. Random House. p. 214. ISBN 0-394-71962-X.

- Goldstein, Doris (October 1977). "J.B. Bury's Philosophy of history: A Reappraisal". The American Historical Review. 82 (4): 897 (896–919). doi:10.1086/ahr/82.4.896. JSTOR 1865117.

- {{cite book |title= History of Freedom of Thought|last= Bury|first= J. B.|date= 1913|publisher= Williams & Norgate |location= London|page=20|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n2FUCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT11

- The Nemean Odes of Pindar, archive.org

- The Isthmian Odes of Pindar, archive.org

- "A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Volume One" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- "A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Volume Two" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- A History of the Roman Empire From its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius, archive.org

- Richards, F. T. (25 November 1893). "Review of A History of the Roman Empire, from its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius by J. B. Bury". The Academy. 44 (1125): 459.

- A History of the Eastern Roman Empire from the Fall of Irene to the Accession of Basil I (A. D. 802–867), archive.org

- A History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, LacusCurtius

- The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians, archive.org

- Thorndike, Lynn (April 1929). "Review of The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians by J. B. Bury". The American Historical Review. 34 (3): 564–566. doi:10.2307/1836287. JSTOR 1836287.

- The Life of St. Patrick and His Place in History, archive.org

- A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great, archive.org

- The Ancient Greek Historians (Harvard Lectures), archive.org

- The Hellenistic Age: Aspects of Hellenistic Civilization, archive.org

- A History of Freedom of Thought, gutenberg.org

- The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into Its Origin and Growth, gutenberg.org

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: J. B. Bury |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: J. B. Bury |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Bagnell Bury. |

- Works by J. B. Bury at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about J. B. Bury at Internet Archive

- Works by J. B. Bury at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)