Irish elk

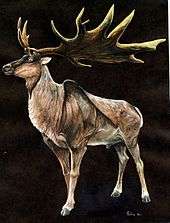

The Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus)[1][2] also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus Megaloceros and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across Eurasia during the Pleistocene, from Ireland into Siberia. Species of the related genus Sinomegaceros occurred in China and Japan. The most recent remains of the species have been carbon dated to about 7,700 years ago in Siberia.[3][4]

| Irish elk | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Mounted skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Cervinae |

| Genus: | †Megaloceros |

| Species: | †M. giganteus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach, 1799) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Although abundant skeletal remains have been found in bogs in Ireland, the animal was not exclusive to Ireland nor closely related to either of the living species currently called elk: Alces alces (the European elk, known in North America as the moose) or Cervus canadensis (the North American elk or wapiti). For this reason, the name "giant deer" is used in some publications, instead of "Irish elk".[5][6][7][8][9] Although one study suggested that the Irish elk was closely related to the red deer (Cervus elaphus),[10] most other phylogenetic analyses support a sister-group relationship with fallow deer (Dama dama).[8][11][12][13]

Taxonomy

Research history

The first scientific descriptions of the animal's remains were made by Irish physician Thomas Molyneux in 1695, who identified large antlers from Dardistown, Dublin—which were apparently commonly unearthed in Ireland—as belonging to the Eurasian elk (called "moose" in North America), concluding that it was once abundant on the island.[14] French scientist Georges Cuvier was the first to challenge that notion, documenting that the Irish elk did not belong to any species of mammal currently living. His study of the Irish elk was a key moment in the history of the study of extinction.

Before the 20th century, the Irish elk, having evolved from smaller ancestors with smaller antlers, was taken as a prime example of orthogenesis (directed evolution), an evolutionary mechanism opposed to Darwinian evolution in which the successive species within the lineage become increasingly modified in a single undeviating direction, evolution proceeding in a straight line void of natural selection. Orthogenesis was claimed to have caused an evolutionary trajectory towards antlers that became larger and larger, eventually causing the species' extinction because the antlers grew to sizes which inhibited proper feeding habits and caused the animal to become trapped in tree branches.[8] In the 1930s, orthogenesis was disputed by Darwinians led by Julian Huxley, who noted that antler size was not grossly large, and was proportional to body size.[15][16] The currently favoured view is that sexual selection was the driving force behind the large antlers rather than orthogenesis or natural selection.[16]

A significant collection of M. giganteus skeletons can be found at the Natural History Museum in Dublin.

Evolution

M. giganteus is one of several species within the genus Megaloceros. The oldest records of the genus are from the late Early Pleistocene.[17] M. giganteus does not appear to be a direct descendant of the common Middle Pleistocene European mid–sized species M. savini. Remains of an indeterminate Megaloceros species from the late Early Pleistocene (~1.2 Ma) of Libakos in Greece are suggested to be closer to M. giganteus than M. savini due to the shared molarisation of the lower fourth premolar (P4).[18] The earliest records of the species comes from Homersfield, Norfolk, thought to be about 450,000 years ago—though the dating is uncertain—and those from Steinheim an der Murr, Germany, (classified as M. g. antecedens) about 400,000–300,000 years ago.[19]

Most remains of the Irish elk are known from the Late Pleistocene. Over 100 individuals have been found in Ballybetagh Bog near Dublin.[21]

Megaloceros is a member of the possibly polyphyletic (invalid) tribe "Megalocerini" or "Megacerini", alongside Megaceroides, Praemegaceros, Eucladoceros and Sinomegaceros.

In 2005, two fragments of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the cytochrome b gene were extracted and sequenced from 4 antlers and a bone. Based on this, Irish elk and red deer may have interbred, which would be unsurprising as hybridisation is known to occur among present-day deer species. It was suggested that, because both have palmated antlers, the Irish elk and fallow deer (Dama spp.) are closely related, but the mtDNA analysis supported a close relation to Cervus.[22] However, a subsequent study in 2015 involving the full mitochondrial genome contradicted this, finding a sister relationship with Dama.[12] This is also supported by morphological analysis of the bony labyrinth, the study also directly suggested that the results of the 2005 study were the result of DNA contamination.[13]

Description

The Irish elk stood about 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulders and carried the largest antlers of any known deer, a maximum of 3.65 m (12.0 ft) from tip to tip and 40 kg (88 lb) in weight. For body size, at about 540–600 kg (1,200–1,300 lb) and up to 700 kg (1,500 lb) or more,[23][24] the Irish elk was the heaviest known cervine ("Old World deer");[11] and tied with the extant Alaska moose (Alces alces gigas) as the third largest known deer. The second and first biggest are Cervalces scotti and C. latifrons, respectively.[23][24] Nonetheless, compared to Alces, Irish elk appear to have had a much more robust skeleton, with older and more mature Alces skeletons bearing some resemblance to those of prime Irish elk, and younger Irish elk resembling prime Alces. Likely due to different social structures, the Irish elk exhibits much more marked sexual dimorphism than Alces, with Irish elk bucks being notably larger than does.[25] In total, Irish elk bucks may have ranged from 450–700 kg (990–1,540 lb), with an average of 575 kg (1,268 lb), and does may have been relatively large, about 80% of buck size, or 460 kg (1,010 lb) on average.[26]

Assuming a similar response to starvation as red deer, a large, healthy Irish elk stag with 40 kg (88 lb) antlers would have had 20-to-28 kg (44-to-62 lb) antlers under poor conditions;[27][24] and an average sized Irish elk stag with 35 kg (77 lb) antlers would have had 18 to 25 kg (40 to 55 lb) antlers under poorer conditions,[28] similar sizes to the moose. A similar change in a typical Irish elk population with prime stags having 35 kg (77 lb) antlers would result in antler weights of 13 kg (29 lb) or less in worsening climatic conditions. This is within the range of present day wapiti/red deer (Cervus spp.) antler weights.[26] Irish elk antlers vary widely in form depending upon the habitat, such as a compact, upright shape in closed forest environments.[28] On islands, the circumference of the base of the antlers reduced by about 41%, and based on this, the total mass was perhaps a fourteenth of those of continental counterparts. This is about 2.7 times more extreme a reduction than what would be expected in red deer.[27] Irish elk likely shed their antlers and re-grew a new pair during mating season. Antlers generally require high amounts of calcium and phosphate, especially those for stags which have larger structures, and the massive antlers of Irish elk may have required much greater quantities. Stags typically meet these requirements in part from their bones, suffering from a condition similar to osteoperosis while the antlers are growing, and replenishing them from food plants after the antlers have grown in or reclaiming nutrients from shed antlers.[24] A finite element analysis of the antlers suggested that during fighting, the antlers were likely to interlock around the middle tine, the high stress when interlocking on the distal tine suggests that the fighting was likely more constrained and predictable than among extant deer, likely involving twisting motions, as is known in extant deer with palmated antlers.[29]

In 1998, Canadian biologist Valerius Geist hypothesised that the Irish elk was cursorial (adapted for running and stamina). He noted that the Irish Elk physically resembled reindeer, and the body proportions of the Irish elk are similar to those of the cursorial addax, oryx, and saiga antelope. These include the relatively short legs, the long front legs nearly as long as the hind legs, and a robust and cylindrical body. Cursorial saiga, gnus, and reindeer have a top speed of over 80 km/h (50 mph), and can maintain high speeds for up to 15 minutes.[26]

Based on Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings, the Irish elk seems to have had overall light colouration, with a dark stripe running along the back, a stripe on either side from shoulder to haunch, a dark collar on the throat and a chinstrap, and a dark hump on the withers (between the shoulder blades). In 1989, American palaeontologist Dale Guthrie suggested that, like bison, the hump allowed a higher hinging action of the front legs to increase stride length while running. The hump may have also been used to store fat. Localising fat rather than evenly distributing it may have prevented overheating while running or in rut during the summer.[26]

Palaeobiology

Reproduction

At Ballybetagh Bog, over 100 Irish elk individuals were found, all small antlered bucks. This indicates that bucks and does segregated during at least winter and spring. Many modern deer species do this in part because males and females have different nutritional requirements and need to consume different types of plants. Segregation would also imply a polygynous society, with stags fighting for control over harems during rut. Because most of the individuals found were juvenile or geriatric and were likely suffering from malnutrition, they probably died from winterkill. It is possible that most Irish Elk specimens known had died from winterkill, and winterkill is the highest source of mortality among many modern deer species. Bucks generally suffer higher mortality rates because they eat little during the autumn rut.[30] For rut, a lean stag normally 575 kg (1,268 lb) may have fattened up to 690 kg (1,520 lb), and would burn through the extra fat over the next month.[26]

The large antlers have generally been explained as being used for male-male battle during mating season.[31] They may have also been used for display,[27] to attract females and assert dominance against rival males.[30]

In deer, gestation time generally increases with body size. A 460 kg (1,010 lb) doe may have had a gestation period of about 274 days. Based on this and patterns seen in modern deer, last year's antlers in Irish elk bucks were potentially shed in early-March, peak antler growth in early-June, completion by mid-July, shedding velvet (a layer of blood vessels on the antlers in-use while growing them) by late-July, and the height of rut falling on the second week of August. Geist, believing the Irish elk to have been a cursorial animal, concluded that a doe would have to have produced nutrient-rich milk so that her calf would have enough energy and stamina to keep up with the herd.[26]

Habitat

Neither exclusive to Ireland nor an elk, it was named so because the most well-known and best-preserved fossil specimens have been found in lake sediments and peat bogs in Ireland. The Irish elk had a far-reaching range, extending from the Atlantic Ocean in the West to Lake Baikal in the East. They do not appear to have extended northward onto the open mammoth steppe, rather keeping to the boreal steppe-woodland environments, which consisted of scattered spruce and pine, as well as low-lying herbs and shrubs including grasses, sedges, Ephedra and Chenopodiaceae.[4] The mesodont condition of the teeth suggests that the species was a mixed feeder, being able to both browse and graze. Pollen remains from teeth found in the North Sea around 43 kya were found to be dominated by Artemisia and other Asteraceae, with minor Plantago, Helianthemum, Plumbaginaceae and Salix.[32] A stable isotope analysis of the terminal Pleistocene Irish population suggests a grass and forb based diet, supplemented by browsing during stressed periods.[33] Dental wear patterns of specimens from the late Middle and Late Pleistocene of Britain suggest a diet tending towards mixed feeding and grazing, but with a wide range including leaf browsing.[34]

Based on the dietary requirements of red deer, a 675 kg (1,488 lb) lean Irish Elk stag would have needed to consume 39.7 kg (88 lb) of fresh forage daily. Assuming antler growth occurred over a span of 120 days, a stag would have required 1,372 g of protein daily, as well as access to nutrient- and mineral-dense forage starting about a month before antlers began sprouting and continuing until they had fully grown. Such forage is not very common, and stags perhaps sought after aquatic plants in lakes. After antler growing, stags could probably satisfy their nutritional requirements in productive sedge lands bordered by willow and birch forests.[26]

The Irish Elk may have been preyed upon by the large carnivores of the time, including the cave lion,[35] and the cave hyena[36]

Extinction

Historically, the extinction of the elk has been attributed to the encumbering size of the antlers, a "maladaptation" making fleeing through forests especially difficult for males while being chased by human hunters,[27] or being too taxing nutritionally when the vegetation makeup shifted.[24] In these scenarios, sexual selection by does for stags with large antlers would have contributed to decline.[37]

However, antler size decreases through the Late Pleistocene and into the Holocene, and so may not have been the primary cause of extinction.[28] A reduction in forest density in the Late Pleistocene and a lack of sufficient high-quality forage is associated with a decrease in body and antler size.[38] Such resource constriction may have cut female fertility rates in half.[28] Human hunting may have forced Irish elk into suboptimal feeding grounds.[3]

The range of the taxon appears to have collapsed during the Last Glacial Maximum, with few remains known between 27.5 and 14.6 kya, with none between 23.3 and 17.5 kya. The remains of the taxon substantially increase during the latest Pleistocene, where it appears to have re-colonised most of its former range, with abundant remains in the UK, Ireland and Germany.[4]

While the range of the taxon was dramatically reduced after the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, it managed to survive in into the early Northgrippian in the western part of its range within European Russia and Siberia, in a belt extending from Maloarchangelsk in the East to Preobrazhenka in the west. It is suggested that extinction was contributed to by further post Holocene transition climatic changes transforming preferred open habitat into uninhabitable dense forest.[4] A Holocene specimen in northern Siberia, dated to approximately 7,700 years ago—well after the end of the last glacial period—shows no sign of nutrient stress, and this specimen came from a region with a continental climate where the forests had not yet gone into decline.[39] The final demise may have been caused by a number of factors both on a continental and regional scale, including climate change and hunting.[38][40]

See also

References

- Geist, Valerius (1998). "Megaloceros: The Ice Age Giant and Its Living Relatives". Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour, and Ecology. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0496-0.

- Lister, A.M. (1987). "Megaceros or Megaloceros? The nomenclature of the giant deer". Quaternary Newsletter. 52: 14–16.

- Stuart, A.J.; Kosintsev, P.A.; Higham, T.F.G.; Lister, A.M. (2004). "Pleistocene to Holocene extinction dynamics in giant deer and woolly mammoth" (PDF). Nature. 431 (7009): 684–689. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..684S. doi:10.1038/nature02890. PMID 15470427. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-14. Supplementary information. Erratum in Stuart, A. J. (2005). "Erratum: Pleistocene to Holocene extinction dynamics in giant deer and woolly mammoth". Nature. 434 (7031): 413. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..413S. doi:10.1038/nature03413.

- Lister, Adrian M.; Stuart, Anthony J. (January 2019). "The extinction of the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach): New radiocarbon evidence". Quaternary International. 500: 185–203. Bibcode:2019QuInt.500..185L. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.03.025.

- Vislobokova, I. A. (2010), Giant Deer: Origin, Evolution, Role in the Biosphere, Paleontological Journal. vol. 46 no. 7 pg. 643-775

- Bro-Jorgensen, J. (2014), "Will their armaments be their downfall? Large horn size increases extinction risk in bovids," Animal Conservation. vol. 17 no. 1 pg. 80-87

- Lemaitre, J. F. (2014), "The allometry between secondary sexual traits and body size is nonlinear among cervids," Biology Letter. vol. 10 no. 3

- Hughes, Sandrine; Hayden, Thomas J.; Douady, Christophe J.; Tougard, Christelle; Germonpré, Mietje; Stuart, Anthony; Lbova, Lyudmila; Carden, Ruth F.; Hänni, Catherine; Say, Ludovic (2006). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (1): 285–291. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.004. PMID 16556506.

- Vislobokova, I. A. (2011), "Historical Development and Geographical Distribution of Giant Deer (Cervidae, Megacerini)", Paleontological Journal. vol. 45 no. 6 pg. 674-688

- Kuehn, Ralph; Ludt, Christian J.; Schroeder, Wolfgang; Rottmann, Oswald (2005). "Molecular Phylogeny of Megaloceros giganteus — the Giant Deer or Just a Giant Red Deer?". Zoological Science. 22 (9): 1031–1044. doi:10.2108/zsj.22.1031. PMID 16219984.

- Lister, Adrian M.; Edwards, Ceiridwen J.; Nock, D. A. W.; Bunce, Michael; van Pijlen, Iris A.; Bradley, Daniel G.; Thomas, Mark G.; Barnes, Ian (2005). "The phylogenetic position of the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus". Nature. 438 (7069): 850–853. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..850L. doi:10.1038/nature04134. PMID 16148942.

- Immel, Alexander; Drucker, Dorothée G.; Bonazzi, Marion; Jahnke, Tina K.; Münzel, Susanne C.; Schuenemann, Verena J.; Herbig, Alexander; Kind, Claus-Joachim; Krause, Johannes (2015). "Mitochondrial Genomes of Giant Deers Suggest their Late Survival in Central Europe". Scientific Reports. 5 (10853): 10853. Bibcode:2015NatSR...510853I. doi:10.1038/srep10853. PMC 4459102. PMID 26052672.

- Mennecart, Bastien; DeMiguel, Daniel; Bibi, Faysal; Rössner, Gertrud E.; Métais, Grégoire; Neenan, James M.; Wang, Shiqi; Schulz, Georg; Müller, Bert; Costeur, Loïc (13 October 2017). "Bony labyrinth morphology clarifies the origin and evolution of deer". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 13176. Bibcode:2017NatSR...713176M. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12848-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5640792. PMID 29030580.

- Molyneux, T. (1695). "A Discourse Concerning the Large Horns Frequently Found under Ground in Ireland, Concluding from Them That the Great American Deer, Call'd a Moose, Was Formerly Common in That Island: With Remarks on Some Other Things Natural to That Country". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 19 (227): 489–512. Bibcode:1695RSPT...19..489M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1695.0083.

- Anderson, Kristina. "What On Earth - A Canadian Newsletter for the Earth Sciences." What On Earth - A Canadian Newsletter for the Earth Sciences. N.p., 15 Nov. 2002. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

- Zimmer, Carl. "The Allure of Big Antlers: The Loom." The Loom. Discover, 3 Sept. 2008. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.

- van der Made, J.; Tong, H.W. (March 2008). "Phylogeny of the giant deer with palmate brow tines Megaloceros from west and Sinomegaceros from east Eurasia". Quaternary International. 179 (1): 135–162. Bibcode:2008QuInt.179..135V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.08.017.

- Van der Made, Jan. 2019. The dwarfed "giant deer" Megaloceros matritensis n.sp. from the Middle Pleistocene of Madrid - A descendant of M. savini and contemporary to M. giganteus. Quaternary International in press. . Accessed 2019-02-04.

- Lister, Adrian M. (September 1994). "The evolution of the giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 112 (1–2): 65–100. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1994.tb00312.x.

- Jaubert, Jacques. L'" art " pariétal gravettien en France : éléments pour un bilan chronologique. OCLC 803593335.

- Johnston, Penny; Kelly, Bernice; Tierney, John. "Megaloceros Giganteus on the Loose" (PDF). Seanda: The NRA Archaeology Magazine. pp. 58–59. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013.

- Kuehn, R.; Ludt, C. J.; Shroeder, W.; Rottmann, O. (2005). "Molecular Phylogeny of Megaloceros giganteus — the Giant Deer or Just a Giant Red Deer?". Zoological Science. 22 (9): 1031–1044. doi:10.2108/zsj.22.1031. PMID 16219984.

- R. D. E. Mc Phee, Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences p.262

- Moen, Ron A.; Pastor, John; Cohen, Yosef (1999). "Antler growth and extinction of Irish elk" (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology Research: 235–249.

- Breda, M. (2005). "The morphological distinction between the postcranial skeleton of Cervalces/Alces and Megaloceros giganteus and comparison between the two Alceini genera from the Upper Pliocene–Holocene of Western Europe". Geobios. 38 (2): 151–170. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2003.09.008.

- Geist, V. (1998). "Megaloceros: the ice age giant and its living relatives". Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour, and Ecology. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0496-0.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1974). "The Origin and Function of 'Bizarre' Structures: Antler Size and Skull Size in the 'Irish Elk,' Megaloceros giganteus". Evolution. 28 (2): 191–220. doi:10.2307/2407322. JSTOR 2407322. PMID 28563271.

- O'Driscoll Worman, Cedric; Kimbrell, Tristan (2008). "Getting to the hart of the matter: Did antlers truly cause the extinction of the Irish elk?". Oikos. 117 (9): 1397–1405. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16608.x.

- Klinkhamer, Ada J.; Woodley, Nicholas; Neenan, James M.; Parr, William C. H.; Clausen, Philip; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R.; Sansalone, Gabriele; Lister, Adrian M.; Wroe, Stephen (2019-10-09). "Head to head: the case for fighting behaviour in Megaloceros giganteus using finite-element analysis". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1912): 20191873. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1873. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6790765. PMID 31594504.

- Barnosky, Anthony D. (19 April 1985). "Taphonomy and Herd Structure of the Extinct Irish Elk, Megalocerous giganteus". Science. New. 228 (4697): 340–344. Bibcode:1985Sci...228..340B. doi:10.1126/science.228.4697.340. PMID 17790237.

- Kitchener, A. (1987). "Fighting behavior of the extinct Irish elk". Modern Geology. 11: 1–28.

- van Geel, B.; Sevink, J.; Mol, D.; Langeveld, B. W.; van der Ham, R. W. J. M.; van der Kraan, C. J. M.; van der Plicht, J.; Haile, J. S.; Rey-Iglesia, A.; Lorenzen, E. D. (November 2018). "Giant deer ( Megaloceros giganteus ) diet from Mid-Weichselian deposits under the present North Sea inferred from molar-embedded botanical remains: GIANT DEER DIET FROM MID-WEICHSELIAN DEPOSITS". Journal of Quaternary Science. 33 (8): 924–933. doi:10.1002/jqs.3069.

- Chritz, Kendra L.; Dyke, Gareth J.; Zazzo, Antoine; Lister, Adrian M.; Monaghan, Nigel T.; Sigwart, Julia D. (November 2009). "Palaeobiology of an extinct Ice Age mammal: Stable isotope and cementum analysis of giant deer teeth". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 282 (1–4): 133–144. Bibcode:2009PPP...282..133C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.08.018.

- Rivals, Florent; Lister, Adrian M. (August 2016). "Dietary flexibility and niche partitioning of large herbivores through the Pleistocene of Britain". Quaternary Science Reviews. 146: 126. Bibcode:2016QSRv..146..116R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.06.007.

- Stuart, A. J.; Lister, A. M. (2011). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17–18): 2337. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2329S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023.

- Diedrich, C. G. (2011). "An Ice Age spotted hyena Crocuta crocuta spelaea (Goldfuss 1823) population, their excrements and prey from the Late Pleistocene hyena den of the Sloup Cave in the Moravian Karst, Czech Republic". Historical Biology. 24 (2): 161–185. doi:10.1080/08912963.2011.591491.

- Kokko, H.; Brooks, R. (2003). "Sexy to die for? sexual selection and the risk of extinction". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 40 (2): 207–219. ProQuest 18804232.

- Gonzalez, Silvia; Andrew Kitchener; Adrian Lister (15 June 2000). "Survival of the Irish elk into the Holocene". Nature. 405 (6788): 753–754. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..753G. doi:10.1038/35015668. PMID 10866185.

- Hughes, S; Hayden, TJ; Douady, CJ; Tougard, C; Germonpré, M; Stuart, A; Lbova, L; Carden, RF; Hänni, C; Say, L (2006). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 40: 285–91. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.004. PMID 16556506. Supplementary data 1, DOC fulltext Supplementary data 2, DOC fulltext Supplementary data 3, DOC fulltext

- Irish Elk Survived after Ice Age Ended Author(s): S. P. Source: Science News, Vol. 166, No. 19 (Nov. 6, 2004), p. 301 Published by: Society for Science & the Public

Further reading

- Kurten, Bjorn (1995): Dance of the Tiger. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20277-5.

- Kurten is a paleo-anthropologist, and in this novel he presents a theory of Neanderthal extinction. Irish elk feature prominently, under the name shelk which Kurten coins (based on the aforementioned old German schelch) to avoid the problematic aspects of "Irish" and "elk" as discussed above. The book was first published in 1980, when the name "Giant Deer" was not yet being used widely.

- ZOOLOGICAL SCIENCE 22: 1031–1044 (2005)

- Juliana, Adelman. "An Insight into Commercial Natural History: Richard Glennon, William Hinchy and the Nineteenth-century Trade in Giant Irish Deer Remains." Archives of Natural History 39.1 (2012): 16–26. Print.

- Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megaloceros giganteus. |

- "Extinct Giant Deer Survived Ice Age, Study Says". National Geographic.

- "CGI picture from Walking with Beasts". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2006.

- "Megaloceros, Irish elk, Giant deer". BBC. Retrieved 25 October 2005.

- "The Case of the Irish Elk". University of California at Berkeley. Archived from the original on 11 November 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2005.