Io (princely title)

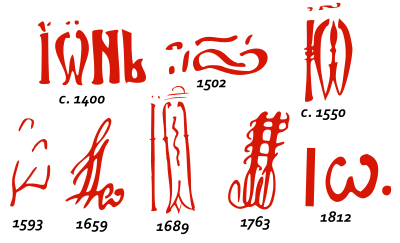

Io (Church Slavonic: Ιω, Iωан or Iωнь; Romanian Cyrillic: Iѡ) is the contraction of a title used mainly by the royalty (hospodars or voivodes) in Moldavia and Wallachia, preceding their names and the complete list of titles. First used by the Asenid rulers of the Second Bulgarian Empire, the particle is the abbreviation of theophoric name Ioan (John), which comes from the original Hebrew Yohanan, meaning "God has favored". Io appeared in most documents (written or engraved), as issued by their respective chancelleries, since the countries' early history; its usage dates back to the foundation of Wallachia, though it spread to Moldavia only in the 15th century.

Initially used with Slavonic and Latin versions of documents, it increasingly appeared in Romanian-language ones after 1600. With time, Io also came to be used by some women of the princely household. It was gradually confounded with the first-person pronoun, Eu, and alternated with the royal we, Noi, until being finally replaced by it in the 19th century.

History

Early usage

The ultimate origin of Io is with the Biblical Yohanan (יוֹחָנָן), a reference to the divine right, and, in the baptismal name "John", an implicit expression of thanks for the child's birth; the abbreviation is performed as with other nomina sacra, but appears as Ioan in Orthodox Church ectenia.[1] The Slavonic Ιω very often features a tilde over the second letter, which is indicative of a silent "n".[2] Io is therefore described by scholar Emil Vârtosu as "both name and title".[3] Its connection to the name "John", and its vocalization as Ioan, are explicitly mentioned by Paul of Aleppo, who visited Wallachia in the 1650s. However, he provides no explanation for why this particular name was favored.[4] Theologian Ion Croitoru argues that Io placed Wallachian and Moldavian Princes under the patronage of John the Evangelist, and that it doubles as a reference to their status as defenders of the Orthodox faith.[5]

The intermediate origin of Io is the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396), located just south of early medieval territories which became Wallachia and Moldavia. As noted by historian A. D. Xenopol, it honors Ivan I Asen, in line with titles such as Caesar and Augustus. He also makes note of its standardized usage by later Asenids, as with the Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander (1355–1356).[6] Xenopol sees the Asenid empire as partly Vlach, and therefore proto-Romanian, but rejects the claim that it ever ruled territories in either Moldavia or Wallachia.[7] Slavist Ioan Bogdan similarly describes Io as borrowed from the Asenids "by diplomatic and paleographic means [...], first in documents, as an imitation of Bulgarian documents, then in other written monuments".[8] The same Bogdan hypothesizes that the title was borrowed in a Moldo–Wallachian context as a posthumous homage to the first Asen rulers, while Nicolae Iorga sees it as a Vlach title which existed in both lands; archivist Damian P. Bogdan suggests a third option, namely that Io was originally a Medieval Greek title used in the Byzantine Empire—a contraction of Ἱωάννης, as used for instance by John II Komnenos and John V Palaiologos.[9]

During Moldavia and Wallachia's early history, the court language was Church Slavonic, using Early Cyrillic. In the 1370s, shortly after Wallachia's creation as an independent polity under the House of Basarab, Vladislav I minted coins with inscriptions in either Renaissance Latin or Slavonic. Only the latter carry variants of Io—Ιω and Iωан; the Latin ones make no such provision.[10] Under Vladislav's brother and successor Radu I, coins in Latin began featuring IONS as a translation of Ιω and contraction of Iohannes.[11] A trove of coins dating back to the rule of Mircea the Elder (1386–1394, 1397–1418) uses IWAN for IONS.[12]

Io only spread to Moldavia only after it became established in Wallachia.[13] For instance, Moldavia's first coin series were all-Latin, and did not use any variant of Io.[14] On various other documents, it alternated with a Slavonic form of the royal we: Мꙑ. As noted by historian Ștefan S. Gorovei, Moldavia's Stephen the Great (reigned 1457–1504) introduced himself using both Ιω (or Iωан) and Мꙑ. The former is always present on stone-carved dedications made by Stephen, and on his version of the Greater Moldavian Seal, but much less so on the Smaller Seal.[15] On only three occasions, the two words were merged into Мꙑ Ιω or Мꙑ Iωан; one of these is a 1499 treaty which also carries the Latin translation, Nos Johannes Stephanus wayvoda.[16] According to Gorovei, it is also technically possible that Stephen's Romanian name was vocalized by his boyars as Ioan Ștefan voievod, since the corresponding Slavonic formula appears in one document not issued by Stephen's own chancellery.[17] A standalone Ιω was also used by Stephen's son and one-time co-ruler Alexandru "Sandrin", and appears as such on his princely villa in Bacău.[18] It makes its first appearance on coins under Bogdan the Blind, who was Stephen's other son, and immediate successor.[19]

The title Ιω could also appear in third-person references, as with church inscriptions and various documents. One early example in Wallachia is Neagoe Basarab's reference to himself and his alleged father, Basarab Țepeluș, named as Io Basarab cel Tânăr.[20] This usage spread to his son and co-ruler Teodosie, who was otherwise not allowed to use a full regnal title. Neagoe would himself be referred to as Io Basarab in a 1633 document by his descendant, Matei Basarab, which unwittingly clarifies that Neagoe was not Țepeluș's son.[21] In the 1530s, Io also appeared in ironic usage, in reference to Vlad Vintilă de la Slatina, who was known to his subjects as Io Braga voievod—referring to his penchant for drinking braga.[22]

While Io entered regular use, and was possibly a name implicitly used by all Princes, these rarely took or kept derivatives of John as their primary names. Before the 17th century, only two Moldavian Princes chose to do so. One was Jacob "John" Heraclides, a foreign-born usurper; the other was John the Terrible, who was likely an illegitimate child, or an impostor.[23] Gorovei proposes the existence of a naming taboo for "Ioan" as a baptismal name, rather than as a title: "I came to the conclusion that princes avoided naming their sons, if born 'in the purple', the name of Ion (Ioan)."[24]

Later stages

The 17th century witnessed a progressive adoption of Romanian as a court vernacular, using the localized Cyrillic alphabet. New Latin variants continued to be featured on coins, as with 1660s Moldavian shillings issued by Eustratie Dabija, or IOHAN ISTRATDORVV; some also had the all-Latin rendition of Ιω as IO.[25] Slavonic continued to appear in princely titles; its use was extended, and it increasingly appeared with female members of the princely families. Possibly the earliest such examples, dated 1597–1600, are associated with Doamna Stanca, wife of Michael the Brave and mother of Nicolae Pătrașcu.[26] Later examples include donations made by Elena Năsturel in 1645–1652. She signs her name as Ιω гспджа Елина зємли Влашкоє ("Io Princess Elina of Wallachia").[27] In the frescoes of Horezu Monastery, completed under Wallachia's Constantin Brâncoveanu, Io is used to describe not just the reigning Prince, but also his wife, Doamna Marica, his mother Stanca, and his late father, Papa Brâncoveanu, who never rose above regular boyardom.[28] The latest appearance of the title alongside a princess is with Doamna Marica, who was also a niece of Antonie Vodă. Ιω is featured on her Slavonic seal of 1689, which she continued to use in 1717—that is, after Prince Constantin had been executed.[29]

Brâncoveanu's downfall inaugurated Phanariote rules, with Princes who spoke Modern Greek, and in some cases Romanian, as their native language. In this new cultural context, Io (Iѡ) preceded statements or signatures in both Romanian and Slavonic, and became confounded with the Romanian first-person singular Eu—which can also be rendered as Io. In 1882, writer Alexandru Macedonski compared the Hurezu murals with the self-styling used by commoners, as in: Eu Gheorghĭe al Petriĭ ("I Gheorghe son of Petru"). On such bases, Macedonski denied that Io was ever a derivative of "John".[30] Historian Petre Ș. Năsturel argues instead that there was a corruption, whereby Io came to be vocalized as a Romanian pronoun, and that this may explain why it was used by princesses.[31] Năsturel points to this transition by invoking a 1631 signature by Lupul Coci (the future Vasile Lupu), "in plain Romanian but with Greek characters": Ιω Λουπουλ Μάρελε Βóρνιχ ("I Lupul the Great Vornic").[32]

Nicholas Mavrocordatos, a Phanariote intellectual who held the throne of both countries at various intervals, also used Latin, in which he was known as Iohannes Nicolaus Alexandri Mavrocordato de Skarlati (1722) and Io Nicolai Maurocordati de Scarleti (1728).[33] Romanian-language documents issued by this Prince, as well as by his competitor Mihai Racoviță, have Slavonic introductions, which include Ιω.[34] Constantine Mavrocordatos used both Io Costandin Nicolae[35] in an all-Romanian text and Noi Costandin Nicolae in a part-Slavonic one.[36] All-Romanian titles were normalized under various other Phanariotes, as with Grigore II Ghica (Io Grigoriu Ghica) and Alexander Mourouzis (Io Alexandrul Costandin Muruz).[37]

Some noted variations were made by other Phanariotes. During his first reign in Wallachia, Alexander Ypsilantis modified the Wallachian arms to include his abbreviated title in Greek letters. Io appeared as IΩ, and twice—as the introductory particle, and as a rendition of Ypsilantis' middle name, Ιωάννης.[38] In 1806, Moldavia's Scarlat Callimachi adopted the Romanian IѡанȢ as his introductory particle. As read by historian Sorin Iftimi, this should mean Io anume ("Io, that is", or "I namely"), rather than the name Ioanŭ.[39] The Phanariote era witnessed reigns by hospodars who were actually named "John". Wallachia's John Caradja was known in his Romanian and Slavonic title as Io Ioan Gheorghe Caragea.[40] In the 1820s, Ioan Sturdza, whose name also translates to "John", did not duplicate it with an introductory particle on various objects produced during his reign;[41] a duplication can still be found on his 1825 frontispiece to Dimitrie Cantemir's Descriptio Moldaviæ, which scholar Cătălina Opaschi reads as Ioanu Ioanu Sandul Sturza.[42]

Iѡ as used by reigning hospodars was gradually replaced in the 18th and 19th centuries by Noi (or Нoi), a localized version of the royal we. A 1783 writ by Alexander Mavrocordatos, regulating the governance of Moldavian Jews, uses both titles—Noi in its introduction, and Io in the princely signature.[43] A variant with the exact spelling Noi appears on the Moldavian Seal used in 1849 by Grigore Alexandru Ghica.[44] Alexandru Ioan Cuza, elected in 1859 as the first Domnitor to rule over both countries (the "United Principalities"), used a transitional mixture of Latin and Cyrillic letters (Нoi Alecsandru Joan 1.) on his Moldavian Seal.[45] Over the following decade, the forgotten origins of Io became the object of scrutiny by historical linguists, beginning in 1863 with an overview by Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu.[46] In 1934, Sextil Pușcariu's general dictionary listed Eu→Io as a popular etymology.[47] The topic endures as "most debated and controversial".[48]

Notes

- Croitoru, pp. 392–394, 406

- Xenopol, p. 147

- Gorovei (2005), p. 45

- Croitoru, p. 406

- Croitoru, pp. 392–394

- Xenopol, p. 147

- Xenopol, pp. 223–230

- Mihăilă, p. 274

- Damian P. Bogdan, "Notițe bibliografice. Dölger Franz, Facsimiles byzantinischer Kaiserurkunden", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. III, Parts II–III, 1933, p. 290

- Moisil, pp. 133–135, 139

- Moisil, pp. 136, 148

- Moisil, p. 418

- Mihăilă, p. 274

- Bița, pp. 194–197

- Gorovei (2005), p. 48

- Gorovei (2005), pp. 45–48

- Gorovei (2005), pp. 47–48

- Ilie, p. 88

- Bița, pp. 196–197

- Ilie, p. 81

- Ilie, pp. 82–83

- Constantin Ittu, "Cnezi ardeleni și voievozi munteni în raporturi cu Sibiul", in Confluențe Bibliologice, Issues 3–4/2007, p. 142

- Gorovei (2014), p. 191

- Gorovei (2014), pp. 190–191

- G. Severeanu, "Monetele lui Dabija-Vodă (1661–1665) și Mihnea-Vodă Radul (1658–1660). Varietăți inedite", in Buletinul Societății Numismatice Române, Vol. XVIII, Issue 48, October–December 1923, pp. 105–109

- Năsturel, pp. 367–368

- Năsturel, pp. 368–369

- Macedonski, p. 525

- Năsturel, pp. 367, 369

- Macedonski, pp. 525–526

- Năsturel, p. 370

- Năsturel, p. 370

- Iftimi, pp. 141–142

- Iorga, passim

- Opaschi, p. 247

- Iorga, p. 33

- Opaschi, pp. 246–248

- Lia Brad Chisacoff, "Filigranul hârtiei produse în timpul primei domnii a lui Alexandru Ipsilanti", in Limba Română, Vol. LX, Issue 4, October–December 2011, pp. 543–545

- Iftimi, pp. 23, 89

- Elena Simona Păun, "Reglementări privind statutul juridic și fiscal al evreilor în Țara Românească (1774–1921)", in Analele Universității din Craiova, Seria Istorie, Vol. XVII, Issue 2, 2012, p. 166; Sterie Stinghe, "Din trecutul Românilor din Schei. Hrisoave, sau cărți domnești de milă și așezământ, prin care se acordă Scheailor dela Cetatea Brașovului unele scutiri și reduceri de dări. Continuare", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 54/1936, p. 2

- Iftimi, pp. 20–21, 70–71

- Opaschi, p. 248

- "Comunicările Societății Istorice Iuliu Barasch. XV. Un hrisov inedit de la 1783", in Revista Israelită, Vol. II, Issue 3, March 1887, p. 83

- Iftimi, p. 90

- Iftimi, pp. 23, 92–93

- Mihăilă, p. 275

- Mihăilă, p. 274

- Gorovei (2005), p. 186

References

- Traian Bița, "Când a devent capul de bour stemă a Moldovei?", in Arheologia Moldovei, Vol. XX, 1997, pp. 187–202.

- Ion Croitoru, "Rolul tiparului în epoca domnului Moldovei Vasile Lupu", in Gheorghe Cojocaru, Igor Cereteu (eds.), Istorie și cultură. In honorem academician Andrei Eșanu, pp. 391–415. Chișinău: Biblioteca Științifică (Institut) Andrei Lupan, 2018. ISBN 978-9975-3283-6-4

- Ștefan S. Gorovei,

- "Titlurile lui Ștefan cel Mare. Tradiție diplomatică și vocabular politic", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, Vol. XXIII, 2005, pp. 41–78.

- "Genealogie dinastică: familia lui Alexandru vodă Lăpușneanu", in Analele Științifice ale Universității Alexandru Ioan Cuza din Iași. Istorie, Vol. LX, 2014, pp. 181–204.

- Sorin Iftimi, Vechile blazoane vorbesc. Obiecte armoriate din colecții ieșene. Iași: Palatul Culturii, 2014. ISBN 978-606-8547-02-2

- Liviu Marius Ilie, "Cauze ale asocierii la tron în Țara Românească și Moldova (sec. XIV–XVI)", in Analele Universității Dunărea de Jos Galați. Series 19: Istorie, Vol. VII, 2008, pp. 75-90.

- Nicolae Iorga, Știri despre Axintie Uricariul. Bucharest: Monitorul Oficial & Cartea Românească, 1934.

- Alexandru Macedonski, "Monumentele istorice. Manastirea Horezu", in Literatorul, Vol. III, Issue 9, 1882, pp. 523–529.

- G. Mihăilă, "'Colecțiunea de documente istorice române aflate la Wiesbaden' și donate Academiei Române de Dimitrie A. Sturdza", in Hrisovul. Anuarul Facultății de Arhivistică, Vol. XIII, 2007, pp. 270–276.

- Constantin Moisil, "Monetăria Țării-Românești în timpul dinastiei Basarabilor. Studiu istoric și numismatic", in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Națională, Vol. III, 1924–1925, pp. 107–159.

- Petre Ș. Năsturel, "O întrebuințare necunoscută a lui 'Io' în sigilografie și diplomatică", în Studii și Cercetări de Numismatică, Vol. I, 1957, pp. 367–371.

- Cătălina Opaschi, "Steme domnești și 'stihuri la gherbul țării' pe vechi tipărituri din Țara Românească și Moldova", in Cercetări Numismatice, Vol. VII, 1996, pp. 245–251.

- A. D. Xenopol, Istoria românilor din Dacia Traiană. Volumul III: Primii domni și vechile așezăminte, 1290—1457. Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 1925.

See also

- Stephen (honorific)

- Kings of Romania