Involuntary treatment

Involuntary treatment (also referred to by proponents as assisted treatment and by critics as forced drugging) refers to medical treatment undertaken without the consent of the person being treated. In almost all circumstances, involuntary treatment refers to psychiatric treatment administered despite an individual's objections. These are typically individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental disorder and are deemed by some form of clinical practitioner, or in some cases law enforcement or others, to be a danger to themselves or to others. Some jurisdictions have more recently allowed for forced treatment for persons deemed to be "gravely disabled" or asserted to be at risk of psychological deterioration. Court approval is typically required outside emergencies, although it is widely claimed that courts often act as "rubber stamps" on such matters.

Effects

A 2014 Cochrane systematic review of the literature found that compulsory community treatment "results in no significant difference in service use, social functioning or quality of life compared with standard voluntary care."[1]

A 2006 review found that as many as 48% of respondents did not agree with their treatment,[2] though a majority of people retrospectively agreed that involuntary medication had been in their best interest.

Law

United States

All states in the U.S. allow for some form of involuntary treatment for mental illness or erratic behavior for short periods of time under emergency conditions, although criteria vary. Further involuntary treatment outside clear and pressing emergencies where there is asserted to be a threat to public safety usually requires a court order, and all states currently have some process in place to allow this. Since the late 1990s, a growing number of states have adopted Assisted Outpatient Commitment (AOC) laws.

Under assisted outpatient commitment, people committed involuntarily can live outside the psychiatric hospital, sometimes under strict conditions including reporting to mandatory psychiatric appointments, taking psychiatric drugs in the presence of a nursing team, and testing medication blood levels. Forty-five states presently allow for outpatient commitment.[3]

In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in O'Connor v. Donaldson that involuntary hospitalization and/or treatment violates an individual's civil rights. The individual must be exhibiting behavior that is a danger to themselves or others and a court order must be received for more than a short (e.g. 72-hour) detention. The treatment must take place in the least restrictive setting possible. This ruling has since been watered down through jurisprudence in some respects and strengthened in other respects. Long term "warehousing", through de-institutionalization, declined in the following years, though the number of involuntary patients has increased dramatically more recently. The statutes vary somewhat from state to state.

In 1979, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit established in Rogers v. Okin that a competent patient committed to a psychiatric hospital has the right to refuse treatment in non-emergency situations. The case of Rennie v. Klein established that an involuntarily committed individual has a constitutional right to refuse psychotropic medication without a court order. Rogers v. Okin established the patient's right to make treatment decisions so long as they are still presumed competent.

Additional U.S. Supreme Court decisions have added more restraints, and some expansions or effective sanctioning, to involuntary commitment and treatment. Foucha v. Louisiana established the unconstitutionality of the continued commitment of an insanity acquittee who was not suffering from a mental illness. In Jackson v. Indiana the court ruled that a person adjudicated incompetent could not be indefinitely committed. In Perry v. Louisiana the court struck down the forcible medication of a prisoner for the purposes of rendering him competent to be executed. In Riggins v. Nevada the court ruled that a defendant had the right to refuse psychiatric medication while he was on trial, given to mitigate his psychiatric symptoms. Sell v. United States imposed stringent limits on the right of a lower court to order the forcible administration of antipsychotic medication to a criminal defendant who had been determined to be incompetent to stand trial for the sole purpose of making them competent and able to be tried. In Washington v. Harper the Supreme Court upheld the involuntary medication of correctional facility inmates only under certain conditions as determined by established policy and procedures.[4]

However, the involuntary treatment of minors remains legally permitted in most states, usually with the consent of a parent or guardian. The use or purported overuse of psychotropic drugs on minors has exploded in recent years, and this fact has received some increased attention from the public, legal experts, former or current patients as well as medical researchers concerned over long-term effects on development.

Proponents and detractors

Supporters of involuntary treatment include organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the American Psychiatric Association, and the Treatment Advocacy Center.

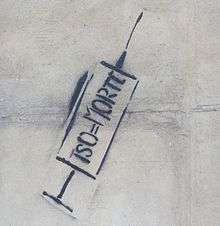

A number of civil and human rights activists, Anti-psychiatry groups, medical and academic organizations, researchers, and members of the psychiatric survivors movement vigorously oppose involuntary treatment on human rights grounds or on grounds of effectiveness and medical appropriateness, particularly with respect to involuntary administration of mind altering substances, ECT, and psychosurgery. Some criticism has been made regarding cost, as well as of conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry. Critics, such as the New York Civil Liberties Union, have denounced the strong racial and socioeconomic biases in forced treatment orders.[5][6]

The Church of Scientology is also aggressively opposed to involuntary treatment.

See also

Related concepts

- Coerced abstinence

- Involuntary commitment (article also addresses psychiatric/psychological treatment as a pretext for politically motivated imprisonment)

- Outpatient commitment

- Political abuse of psychiatry (also known as "political psychiatry" and as "punitive psychiatry")

- Social control

- Specific jurisdictions' provisions for a temporary detention order for the purpose of mental-health evaluation and possible further voluntary or involuntary commitment:

- United States of America:

- California: 5150 (involuntary psychiatric hold) and Laura's Law (providing for court-ordered outpatient treatment)

- Lanterman–Petris–Short Act, codifying the conditions for and of involuntary commitment in California

- Florida: Baker Act and Marchman Act

Notable activists

- Giorgio Antonucci (elimination)

- Thomas Szasz (elimination)

- Robert Whitaker (reduction)

- E. Fuller Torrey (expansion)

- DJ Jaffe (expansion)

Advocacy organizations

- Mental Health America (reduction/modification)

- Mad in America (reduction/elimination)

- PsychRights (reduction/elimination)

- Anti-psychiatry, also known as the "anti-psychiatric movement" (reduction/elimination)

- Citizens Commission on Human Rights (reduction/elimination; founded as a joint effort of the anti-psychiatric Church of Scientology and libertarian mental-health-rights advocate Thomas Szasz)

- MindFreedom International (reduction/elimination)

- Treatment Advocacy Center (expansion)

- Mental Illness Policy (expansion)

- NAMI (expansion)

References

- Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Kisely SR, Campbell LA. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD004408. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub4

- Katsakou C, Priebe S (October 2006). "Outcomes of involuntary hospital admission—a review". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 114 (4): 232–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00823.x. PMID 16968360.

- "Browse by State".

- "Washington et al., Petitioners v. Walter Harper". Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, Inc., "Implementation of Kendra's Law is Severely Biased" (April 7, 2005) http://nylpi.org/pub/Kendras_Law_04-07-05.pdf Archived 28 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- [ NYCLU Testimony On Extending Kendra's La NYCLU Testimony On Extending Kendra's Law]

External links

- National Mental Health Consumers' Self-Help Clearinghouse

- Psychlaws.org — 'Keys to Commitment' (a guide for family members), Robert J. Kaplan, JD

- Rogers Law, concerning involuntary treatment/commitment in Massachusetts