Inverkeithing

Inverkeithing (/ˌɪnvərˈkiːðɪŋ/ ![]()

| Inverkeithing | |

|---|---|

View of Inverkeithing | |

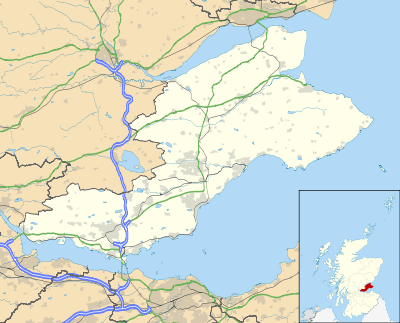

Inverkeithing Location within Fife | |

| Population | 4,890 [3] |

| OS grid reference | NT130829 |

| • Edinburgh | 9 mi (14 km) S |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Inverkeithing |

| Postcode district | KY11 |

| Dialling code | 01383 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

It is situated about 9 miles (15 km) north from Edinburgh Airport and about 4 miles from the centre of Dunfermline. Modern Inverkeithing is almost contiguous with Rosyth and Dalgety Bay. Inverkeithing is a developing town and has many new housing sites, including one next to the town's railway station. It is a busy commuter town, and trains to and from several large towns and cities call at the station. The town is also home to the Ferrytoll Park & Ride, and is served by many buses.

The civil parish has a population of 8,090 (in 2011).[4]

Origin of name

The name is of Scottish Gaelic origin, Inbhir Céitein. Inbhir means "confluence, inflow", thus "mouth of the Keithing/Céitein". The Keithing is the name of a small river or burn that runs through the southern part of the town. Taylor (2006) notes that the name Keithing probably contains the Pictish (Brythonic) *coet, "wood", so the Keithing burn would have meant "stream that runs through or past or issues from woodland".[5][6]

History

Inverkeithing has ancient origins, with some evidence dating back to Agricola's excursion into Northern Scotland in AD 83.[7] The area was well settled by the 5th century, when a church was founded here by St Erat, a follower of St Ninian.

Inverkeithing is first documented in 1114, when it is mentioned in the foundation charter of Scone Abbey granted by Alexander I.[8] In 1163 it appears – as "Innirkeithin" – in Pope Alexander III's summons of the clergy of the British Isles to the Council of Tours.[9] Inverkeithing was one of Fife's first royal burghs, in existence as such by the early 1160s, during the reign of Malcolm IV. It is with Inverkeithing's promotion to burgh status, which conferred particular legal and trading privileges on a settlement, that records become clearer for the town. Inverkeithing was an obvious choice for the King to grant burgh status, given its strategic location on the coast at the narrowest crossing point of the Firth of Forth, with a sheltered bay.[7]

The town was also the last place that Alexander III was seen before he died in a fall from his horse at Kinghorn in 1286. Some texts say he fell off a cliff,[10] and although there are no cliffs where his body was found, there is a very steep rocky embankment, which "would have been fatal in the dark."[11]

Edward I of England ("Longshanks") stayed in Inverkeithing on 2 March 1304 on his return to Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence. This is evidenced by letters written here as he made his way from Dunfermline to St Andrews.[12]

A Franciscan friary was established in Inverkeithing around the mid-14th century, and the above-ground remains may have been the guesthouse or hospitium, but were remodelled as a tenement in the 17th century. The friary garden contains other remains of the original complex, such as stone vaults which were probably storage cellars. The friary would have been a convenient stopping-off point for pilgrims crossing by the Queen's Ferry en route to St Andrews, and would have contributed to the burgh's prosperity. It is one of the few remnants of a house of the Greyfriars to have survived in Scotland.

16th and 17th centuries

Although ditches and wooden palisades were a common means for early Scottish burghs to distance themselves from the surrounding countryside – as well as to collect tolls and to control access – Inverkeithing was one of the few to have four stone "ports" (gates) surrounding its initially small medieval settlement. Stone walls were added in 1557, a remnant of which can be seen on the south side of Roman Road – the only trace of the medieval walling to remain in Inverkeithing. Until that time, Inverkeithing enjoyed a successful trade in wool, fleece and hides, and was considered a hub of trade for the whole of Scotland. As a thriving medieval burgh, Inverkeithing had weekly markets and five annual fairs.[7]

Trade had begun to decrease by the 16th century, and Inverkeithing paid less tax than other nearby burghs as a result of its comparative poverty. But due to political and social instability, caused by both plague and war, Inverkeithing continued to grow poorer in the 17th century. In 1654, Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu mentions Inverkeithing as "formerly a flourishing market" in his Nova Fifae Descriptio.

Inverkeithing was a hotbed for witch trials in the 17th century. In 1621 six Inverkeithing women, Bessie Harlaw, Bessie Chalmers, Beatrice Mudie, Christiane Hamilton, Margaret Kent, and Marion Chatto, were tried for witchcraft in the Tolbooth.[13] Between 1621 and 1652, at least 51 people were executed for witchcraft in Inverkeithing, an unusually large number for a town of this size; the much larger Kirkcaldy only saw 18 executions in the same period.[14] The reason is believed to be a combination of cholera outbreaks, famine, and the appointment of Rev. Walter Bruce – a known witch hunter – as minister of St Peter's.[15] Bruce also played a pivotal role in initiating the so-called Great Scottish witch hunt of 1649-50. The executions were carried out at Witch Knowe, a meadow to the south of town, which today is partially within the boundaries of Hope Street Cemetery.[15][16]

The Battle of Inverkeithing in 1651 was fought on two sites in the area, one north of the town close to Pitreavie Castle, the other to the south on and around the peninsula of North Queensferry and the isthmus connecting it to Inverkeithing. The battle took place during Oliver Cromwell's invasion of the Kingdom of Scotland following the Third English Civil War. It was an attempt by the English Parliamentarian forces to outflank the army of Scottish Covenanters loyal to Charles II at Stirling and get access to the north of Scotland.[17] This was the last major engagement of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and led to Scotland passing into Cromwell's control. Cromwell's troops crushed the Scots, forcing them to abandon Stirling and march south to support Charles II. Of the estimated 800 MacLean clansmen who fought in the battle, only 35 were said to have survived. The Pinkerton Burn was said to have run red with blood for days afterwards. This was a significant episode in the history of Clan MacLean, and the 20th century poet Sorley MacLean mentions Inverkeithing in one of his poems.

Modern era

Daniel Defoe, writing of Inverkeithing in the early 18th century, found it to be a "walled town still populous though greatly decayed".[18] At the time, the parish had a population of over 2,200,[12] but industry had become smaller in scale, although increasingly diverse. Lead and coal were mined, with coal exported in substantial quantities. There was an iron foundry, and by the late 18th century the town had a distillery, a brewery, tan works, soap works, a salt pan and timber works.[7] The importance of fishing declined in line with increasing industrialisation, and by 1891 Inverkeithing only had 14 resident fishermen.[19]

By the 19th century quarrying, engineering and shipbuilding were major industries in the area, and in 1831 the population is recorded as having increased by over 600 in a decade due to an influx of labourers employed in the greenstone quarries. These provided material for major works such as the extension of Leith Pier, and some of the piers of the Forth Bridge.[12] By 1870, engineering and shipbuilding had ceased, and the harbour lost freight traffic to the railways, so that for the first time Inverkeithing was not on a through route for freight. The opening of the Forth Bridge in 1890, however, led to a surge in incomers and new building. By 1925, quarrying remained a major operation, and whilst the saltworks, distillery, iron foundry and sawmill were no longer in operation, a successful papermaking industry developed at the harbour.[7]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Inverkeithing became famous for its shipbreaking at Thos W Ward's yard. The revolutionary battleship HMS Dreadnought was dismantled here in 1923, as was the hull of the Titanic's sister ship RMS Olympic in 1937, and the second RMS Mauretania in 1966. Today the yard is a metal recycling facility.

Notable people

- Gordon Durie, ex East Fife, Glasgow Rangers, Chelsea and Scotland striker studied at Inverkeithing High School

- Samuel Greig, Russian admiral and "Father of the Russian Navy", was a native of Inverkeithing

- Stephen Hendry MBE, former professional snooker player and multiple world champion, went to Inverkeithing High School[20]

- Craig Levein, ex manager and ex director of football at Heart of Midlothian, studied at Inverkeithing High School and played for the under-16s team[21]

- Sir Duncan McDonald FRSE, engineer and industrialist

- Natalie McGarry, SNP politician and former Member of Parliament for Glasgow East[22]

- Robert Moffat, missionary to Africa and father-in-law of explorer David Livingstone, lived here during his early years[23]

- David Spence, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Rev Alexander Stoddart Wilson, minister and botanist, died in Inverkeithing and is buried there

Governance

Inverkeithing forms part of the Dunfermline and West Fife Westminster constituency, currently (2019) held by Douglas Chapman MP for the Scottish National Party (SNP).[24] For the Scottish Parliament Inverkeithing forms part of the Cowdenbeath constituency[25] which falls within the Mid Scotland and Fife electoral region. The constituency is represented (2019) by Annabelle Ewing, also of the SNP.[26]

Landmarks

The heart of the medieval town is around the High Street and Church Street.[27] The B-listed parish church of St. Peter stands in its large churchyard on the east side of Church Street. It was first built as a wooden Celtic church before being adapted into a Norman stone structure, which was bequeathed by the monks of Dunfermline Abbey in 1139.[27] The Norman foundations were reused for the 13th century Gothic structure, and a tower was added in the 14th century. Extensive fire damage in 1825 reduced it to the height of its lower window sills, although the tower survived, but it was rebuilt.[27] The main part of the church is thus a large plain neo-Gothic 'preaching box' of 1826–27. The traceried belfry openings are unusual. Built of soft sandstone, the tower – the only remaining part of the pre-Reformation church – is very weathered, and has been partially refaced. It is crowned by a lead spire with elaborate gabled dormers housing clock faces (1835 and 1883).

The church's roomy interior (now deprived of its galleries) is graced by a little-known treasure, one of the finest medieval furnishings to survive in any Scottish parish church. This is the large, extremely well preserved, grey sandstone font of around 1398, which was rediscovered buried under the church, having been concealed at the Reformation. Its octagonal bowl is decorated with angels holding heraldic shields. These include the royal arms of the King of Scots, and of Queen Anabella Drummond (d.1401), the consort of Robert III (1390–1406). The high quality of the carving is explained by it being a royal gift to the parish church, Inverkeithing being a favourite residence of Queen Anabella.

On the High Street is the category A listed building, the Hospitium of the Grey Friars, one of the best surviving example of a friary building in Scotland.[28] The bulk of the building dates from the 14th century, and it was remodeled into a tenement after the Reformation in the 17th century, and became a museum in 1934–1937.[28] The building is now used as a social community centre.

The town also contains one of the finest examples remaining of a mercat cross in Scotland.[27] The cross, a Grade-A listed monument, is said to have been built as a memorial of the marriage of the Duke of Rothesay with the daughter of the Earl of Douglas.[27] Originally, the cross stood on the north end of the High Street, before moving to face the tollbooth and then to its present site at the junction between Bank Street and High Street, further up the road.[27][29][30] As of 2020, there are plans to move it again, to a more prominent position in the Market Square, as part of a ₤3.6 million, five-year programme of improvements designed to boost tourism in the town.[31]

The core of the mercat cross is said to date from the late 14th century, with the octagonal shaft from the 16th century.[27][29] Two of the shields on the cross bear the arms of Queen Anabella Drummond and the Douglas family.[27] Later, a unicorn and a shield depicting the St Andrew's Cross were added in 1688, the work of John Boyd of South Queensferry.[27][30]

Located on Bank Street, between numbers 2–4, is Thomsoun's House, which dates from 1617 and was reconstructed in 1965.[29]

Opposite St Peter's Church is the A-listed L-plan tower house known as Fordell Lodgings, which dates from 1671 and was built by Sir John Henderson of Fordell.[27] Behind Fordell Lodgings is the C-listed building of the former Inverkeithing Primary School, built in 1894. The building suffered a large fire in November 2018.[32] On King Street is the much altered B-listed Rosebery House, once owned by the Rosebery family,[27] and possibly the oldest surviving house in the burgh.[33] The unusual monopitch lean-to roof is locally known as a 'toofall', and dates the house to no later than the early 16th century.[33] It was owned by the Earl of Dunbar before being purchased by the Earl of Rosebery.[27]

On Townhall Street is the A-listed Inverkeithing Tolbooth, which displays the old town coat of arms, above the front door.[27][29] The Renaissance tower, at the western end of the building, is the oldest part of the tolbooth, dating from 1755.[30] A three-storey classical building followed in 1770 as a replacement for the previous tolbooth.[30] This consists of a prison or the 'black hole' on the ground floor, the court room on the middle and the debtors' prison on the top.[30]

Inverkeithing Cemetery

Inverkeithing Cemetery was created around 1870 to replace the churchyard at St Peter's. It lies south-west of the town on a hill road and is accessed under the railway line.

Despite being sandwiched between the railway line and the M90 motorway, it is quite tranquil; but its isolation has led to much vandalism, especially in the upper area.

Transport

Inverkeithing is bypassed by the M90 motorway. The M90 links Fife to Lothian and Edinburgh via the Queensferry Crossing. The town is also served by Inverkeithing railway station, a hub for the rail network to and from Fife. Passengers travelling to Edinburgh are carried over the Forth Bridge.

Inverkeithing and its hinterland are also served by the Ferrytoll Park and Ride, off Hope Street, which provides car parking and access to bus services to Edinburgh city centre, South Gyle, Edinburgh Airport, Livingston and many parts of Fife, as well as links to the Scottish Citylink coach network.

References

- Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba ~ Gaelic Place-names of Scotland

- "Scotslanguage.com – Names in Scots – Places in Scotland". www.scotslanguage.com.

- "Estimated population of localities by broad age groups, mid-2016". National Records of Scotland. 2016.

- Census of Scotland 2011, Table KS101SC – Usually Resident Population, publ. by National Records of Scotland. Web site http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ retrieved March 2016. See "Standard Outputs", Table KS101SC, Area type: Civil Parish 1930

- Taylor, Simon (2006) The Place-Names of Fife, Shaun Tyas, Donington

- "Fife Place-name Data :: Inverkeithing". fife-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk.

- "Inverkeithing Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). Fife Council. 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Notes on Inverkeithing Parish Church and the Royal Burgh of Inverkeithing" (PDF). Inverkeithing Parish Church. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Jones, John A. Rupert (1917). Rosyth. Dunfermline: A. Romanes & Son. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Wood, James, ed. (1920). The Nuttall Encyclopaedia. London: Warne. p. 13.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Mount, Toni (2015). Dragon's Blood & Willow Bark: The Mysteries of Medieval Medicine. Stroud, Glos.: Amberley. p. 23. ISBN 978-1445643830.

- Millar, Alexander (1895). Fife: Pictorial and Historical; its people, burghs, castles, and mansions. Cupar: A. Westwood & Son. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1895), p. 423.

- "Witches Data Visualization Project". University of Edinburgh.

- "How a small Fife town became a 'hotbed of witch-finding and punishing'". The Scotsman.

- "Ordnance Survey Map 1896 – Fifeshire XLIII.2 (Dunfermline; Inverkeithing)". National Library of Scotland.

- "Historic Environment Scotland". www.historicenvironment.scot.

- Daniel Defoe, Letter XIII, A Tour Through the Whole Islands of Great Britain

- Mackay, Aeneas (1896). The County Histories of Scotland: Fife and Kinross. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "The boy who went to pot". The Herald. 24 May 1994.

- https://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle-2-15039/meet-the-fifer-who-knows-the-score-1-1027682

- "MP from Inverkeithing charged with alleged fraud". Dunfermline Press.

- "Livingstone's Pathfinder". Lothian Life.

- "Douglas Chapman MP". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Cowdenbeath constituency map" (PDF). Boundary commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Annabelle Ewing MSP". The Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Lamont-Brown Fife in History and Legend pp.162–164.

- Fife Regional Council Medieval Abbeys and Historic Churches p.40.

- Pride Kingdom of Fife p.35.

- Walker and Ritchie Fife, Perthshire and Angus pp.82–83.

- "Mercat Cross to be relocated as part of ₤3.6m redevelopment" - The Courier, 8 May, 2020

- "Fire destroys former primary school in Inverkeithing". BBC. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "9 King Street, Rosebery House". Historic Environment Scotland.