Industrial Revolution in the United States

The Industrial Revolution involved a shift in the United States from manual labor-based industry to technical based industry which greatly increased the overall production and economic growth of the United States, signifying a shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy widely accepted to have been a result of Samuel Slater's introduction of British Industrial methods in textile manufacturing to the United States,[1] and necessitated by the War of 1812.[2]

Origins

As Western Europe began industrializing in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the United States remained agrarian in nature with resource processing, such as gristmills and sawmills being its major semi-industrial pursuit,[3] however, as demand for U.S. resources increased, canals and railroads became extremely important to economic growth due to sparse population[4] particularly in areas where resources were rich such as in the Western frontier. This made it necessary for the U.S. to expand its technological capabilities, which led to an Industrial Revolution reaching American shores as entrepreneurs competed and learned from each other to develop better technology, fundamentally and permanently altering the U.S. economy, thrusting it into the new age of industrialization. Much of the technology that initiated the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. was pirated from British designs by ambitious British entrepreneurs hoping to use the technology to create successful companies in the U.S.[5]

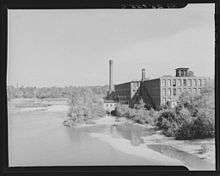

The entrepreneur who initially brought the textile technology typically associated with Industrial Revolution to the U.S. was Samuel Slater. Widely considered the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution",[6] Samuel Slater, was born in Belper, Derbyshire, England on June 9, 1768, and began working at a cotton mill from age 10. He learned that Americans were interested in the Industrial Revolution's new techniques, but since exporting such designs were illegal in England, he memorized as much as he could and departed for New York in 1789 illegally. Moses Brown, a leading Rhode Island industrialist, attempted to operate a mill with a 32-spindle frame in Pawtucket, but he couldn't. It was at that time that Slater offered his services, promising to replicate British designs for Brown and, after an initial investment by Brown to Slater to fulfill initial requirements, the mill successfully opened in 1793 being the first water-powered roller spinning textile mill in the Americas. By 1800, Slater's mill had been duplicated by many other entrepreneurs as Slater grew wealthier and his techniques more and more popular, which brought him the name "Father of the American Industrial Revolution" by Andrew Jackson in the U.S., but also the name "Slater the Traitor" by many in Great Britain who felt he betrayed them to the Americans.[7]

Progression of the First Industrial Revolution

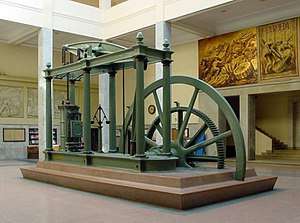

The First Industrial Revolution was marked by shift in labor. Labor in the United States began to shift from an outwork system of labor to a factory system of labor. Throughout the First Industrial Revolution, which lasted into the mid nineteenth century, much of the U.S. population remained in small scale agriculture.[8] Despite a minor percentage of the population working in industry at the time, the U.S. government did take action to try and expand and aid U.S. industry. This can be seen early in the nation's history with Alexander Hamilton's proposal of the "American School" ideas which supported high tariffs in order to protect U.S. industry.[9] This idea was embraced by the Whig Party in the early nineteenth century with their support for Henry Clay's American System. This plan, proposed shortly after the War of 1812, supported not only tariffs to protect U.S. industry but also canals and roads to support the movement of manufactured goods around the country.[10] As was the case in Britain, the first Industrial Revolution in the United States revolved heavily around the textile industry. Early U.S. textile plants were located next to rivers and streams as they would use the running water the power the machinery in the plant. This meant that much of the factories of the First Industrial Revolution existed in the Northeastern United States[11]

To aid the expansion of industry, Congress chartered the Bank of the United States in 1791, giving loans to help merchants and entrepreneurs secure necessary capital. However, Jeffersonians saw this bank as an unconstitutional expansion of federal power, so when its charter expired in 1811, the Jeffersonian-dominated Congress did not renew it.[12] State legislatures were persuaded to charter their own banks to continue helping merchants, artisans, and farmers who needed loans, and, by 1816, there were 246 state-chartered banks. With these banks, states were able to support internal transportation improvements, such as the Erie Canal, which stimulated economic development.[13]

Effects Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution permanently altered the U.S. economy and set the stage for the United States to dominate technological change and growth in the Second Industrial Revolution[14] in its Gilded Age. The Industrial Revolution also saw a decrease in the rampancy of labor shortages which characterized the U.S. economy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[15] This was because there was a "transportation revolution" that happened in the same period, which was massively important due to the sheer size and low population density of the U.S. at the time, connecting population centers such as through the Wilderness Road and the Erie Canal, coupled with the development of steamboats and rail transport, allowing for the phenomenon of urbanization to begin which increased the labor force available around larger cities such as New York City and Chicago, ameliorating the classic American labor shortages of the time. This also allowed for the quicker movement of resources and goods around the country, drastically increasing trade efficiency and output, while allowing for an extensive transport base for the U.S. to grow from in the Second Industrial Revolution.[16]

Techniques to make interchangeable parts were developed in the US, and allowed easy assembly and repair of firearms or other devices, minimizing the time and skill needed to repair or assemble devices. By the beginning of the Civil War, rifles with interchangeable parts had been developed, and after the war, more complex devices such as sewing machines and typewriters were made with interchangeable parts.[17] In 1798, Eli Whitney obtained a government contract to manufacture 10,000 muskets in less than two years. By 1801, he had failed to produce a single musket and was called to Washington to justify his use of Treasury funds. There, he created a demonstration for Congress in which he assembled muskets from parts chosen randomly from his supply.[18] While this demonstration was later proved to be fake, it popularized the idea of interchangeable parts, and Eli Whitney continued using the concept to allow relatively unskilled laborers to produce and repair weapons quickly and at a low cost. Another important innovator is Thomas Blanchard, who in 1819 invented the Blanchard lathe, which could produce identical copies of wooden gun stocks.[19]

Interchangeable parts made the development of the assembly line possible. In addition to making production faster, the assembly line eliminated the need for skilled craftsmen because each worker would only do one repetitive step instead of the entire process.[20]

First Industrial Revolution had a profound effect on labor in the U.S. Companies from the era, such as the Boston Associates, would recruit thousands of New England farm girls to work in textile mills. This practice was beneficial for both the employer and the employee as young girls often demanded much lower wages than men and this factory work gave young women a sense of independence that they did not feel working on a farm. The First Industrial Revolution also marked the beginning of the rise of wage labor in the United States. As wage labor grew over the next century, it would go on to profoundly change American Society.[21]

See also

References

- "The Industrial Revolution in the United States - Primary Source Set | Teacher Resources - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- "Significant Events of the American Industrial Revolution". About.com Education. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- Taylor, George Rogers (1969). The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860. ISBN 978-0873321013.

- Chandler Jr., Alfred D. (1993). The Visible Hand: The Management Revolution in American Business. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674940529

- "Economic Growth and the Early Industrial Revolution [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- "The First American Factories [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- Heath, Neil. "Samuel Slater: American hero or British traitor?". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "The American System of Economics | American Jobs Alliance". www.americanjobsalliance.com. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "U.S. Senate: Classic Senate Speeches". www.senate.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- "Economic Growth and the Early Industrial Revolution [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- Henretta (2018). America's history: for the AP course. Hinderaker, Edwards, Rebecca, Self (Ninth ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martins. pp. 240, 241. ISBN 978-1-319-06507-2. OCLC 1076274245.

- "Economic Growth and the Early Industrial Revolution [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Vatter, Harold G.; Walker, John F.; Alperovitz, Gar (June 1995). "The onset and persistence of secular stagnation in the U.S. economy: 1910–1990, Journal of Economic Issues".

- Habakkuk, H. J. (1962). American and British Technology in the Nineteenth Century. London, U.K., New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521094474

- Eugene S. Ferguson, Oliver Evans, Inventive Genius of the American Industrial Revolution (Hagley Museum & Library, 1980).

- "No. 1252: Interchangeable Parts". uh.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- Editors, History com. "Interchangeable Parts". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-05-21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Thomas Blanchard" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "On the Line Mass production forever alters the lives of workers and consumers". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Economic Growth and the Early Industrial Revolution [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2020-05-22.