Hyperloop

A Hyperloop is a proposed mode of passenger and freight transportation, first used to describe an open-source vactrain design released by a joint team from Tesla and SpaceX.[1] Hyperloop is a sealed tube or system of tubes with low air pressure through which a pod may travel substantially free of air resistance or friction.[2] The Hyperloop could convey people or objects at airline or hypersonic speeds while being very energy efficient.[2] This would drastically reduce travel times versus trains as well as planes[2] over distances of under approximately 1,500 kilometres (930 miles).[3]

Elon Musk first publicly mentioned the Hyperloop in 2012.[4] His initial concept incorporated reduced-pressure tubes in which pressurized capsules ride on air bearings driven by linear induction motors and axial compressors.[5]

The Hyperloop Alpha concept was first published in August 2013, proposing and examining a route running from the Los Angeles region to the San Francisco Bay Area, roughly following the Interstate 5 corridor. The Hyperloop Genesis paper conceived of a hyperloop system that would propel passengers along the 350-mile (560 km) route at a speed of 760 mph (1,200 km/h), allowing for a travel time of 35 minutes, which is considerably faster than current rail or air travel times. Preliminary cost estimates for this LA–SF suggested route were included in the white paper—US$6 billion for a passenger-only version, and US$7.5 billion for a somewhat larger-diameter version transporting passengers and vehicles.[1] (Transportation analysts had doubts that the system could be constructed on that budget. Some analysts claimed that the Hyperloop would be several billion dollars overbudget, taking into consideration construction, development, and operation costs.)[6][7][8]

The Hyperloop concept has been explicitly "open-sourced" by Musk and SpaceX, and others have been encouraged to take the ideas and further develop them. To that end, a few companies have been formed, and several interdisciplinary student-led teams are working to advance the technology.[9] SpaceX built an approximately 1-mile-long (1.6 km) subscale track for its pod design competition at its headquarters in Hawthorne, California.[10]

Currently, India is the only country that is officially pursuing the hyperloop technology for Pune-Mumbai corridor. [11]

History

The general idea of trains or other transportation traveling through evacuated tubes dates back more than a century, although the atmospheric railway was never a commercial success.

Musk first mentioned that he was thinking about a concept for a "fifth mode of transport", calling it the Hyperloop, in July 2012 at a PandoDaily event in Santa Monica, California. This hypothetical high-speed mode of transportation would have the following characteristics: immunity to weather, collision free, twice the speed of a plane, low power consumption, and energy storage for 24-hour operations.[12] The name Hyperloop was chosen because it would go in a loop. Musk envisions the more advanced versions will be able to go at hypersonic speed.[13] In May 2013, Musk likened the Hyperloop to a "cross between a Concorde and a railgun and an air hockey table".[14]

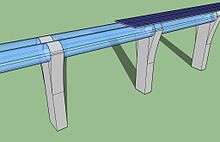

From late 2012 until August 2013, a group of engineers from both Tesla and SpaceX worked on the conceptual modeling of Hyperloop.[15] An early system design was published in the Tesla and SpaceX blogs[1][16] which describes one potential design, function, pathway, and cost of a hyperloop system.[1] According to the alpha design, pods would accelerate to cruising speed gradually using a linear electric motor and glide above their track on air bearings through tubes above ground on columns or below ground in tunnels to avoid the dangers of grade crossings. An ideal hyperloop system will be more energy-efficient,[17][18] quiet, and autonomous than existing modes of mass transit. Musk has also invited feedback to "see if the people can find ways to improve it". The Hyperloop Alpha was released as an open source design.[19] The word mark "HYPERLOOP", applicable to "high-speed transportation of goods in tubes" was issued to SpaceX on April 4, 2017.[20][21]

In June 2015, SpaceX announced that it would build a 1-mile-long (1.6 km) test track to be located next to SpaceX's Hawthorne facility. The track would be used to test pod designs supplied by third parties in the competition.[22][23]

By November 2015, with several commercial companies and dozens of student teams pursuing the development of Hyperloop technologies, the Wall Street Journal asserted that "The Hyperloop Movement", as some of its unaffiliated members refer to themselves, is officially bigger than the man who started it."[24]

The MIT Hyperloop team developed the first Hyperloop pod prototype, which they unveiled at the MIT Museum on May 13, 2016. Their design uses electrodynamic suspension for levitating and eddy current braking.[25]

On January 29, 2017, approximately one year after phase one of the Hyperloop pod competition,[26] the MIT Hyperloop pod demonstrated the first ever low-pressure Hyperloop run in the world.[27] Within this first competition the Delft University team from the Netherlands achieved the highest overall competition score, winning the prize for "best overall design".[28][29] The award for the "fastest pod" was won by the team WARR Hyperloop from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), Germany.[30] The team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) placed third overall in the competition, judged by SpaceX engineers.[31]

The second Hyperloop pod competition took place from August 25–27, 2017. The only judging criteria was top speed, provided it was followed by successful deceleration. WARR Hyperloop from the Technical University of Munich won the competition by reaching a top speed of 324 km/h (201 mph) and therefore breaking the previous record of 310 km/h for Hyperloop prototypes set by Hyperloop One on their own test track.[32][33][34]

A third Hyperloop pod competition took place in July 2018. The defending champions, the WARR Hyperloop team from the Technical University of Munich, beat their own record with a top speed of 457 km/h (284 mph) during their run.[35]

The fourth competition in August 2019 saw the team from the Technical University of Munich, now known as TUM Hyperloop (by NEXT Prototypes e.V.),[36] again winning the competition and beating their own record with a top speed of 463 km/h (288 mph).[29]

Theory and operation

Developments in high-speed rail have historically been impeded by the difficulties in managing friction and air resistance, both of which become substantial when vehicles approach high speeds. The vactrain concept theoretically eliminates these obstacles by employing magnetically levitating trains in evacuated (airless) or partly evacuated tubes, allowing for speeds of thousands of miles per hour. However, the high cost of maglev and the difficulty of maintaining a vacuum over large distances has prevented this type of system from ever being built. The Hyperloop resembles a vactrain system but operates at approximately one millibar (100 Pa) of pressure.[37]

Initial design concept

The Hyperloop concept operates by sending specially designed "capsules" or "pods" through a steel tube maintained at a partial vacuum. In Musk's original concept, each capsule floats on a 0.02–0.05 in (0.5–1.3 mm) layer of air provided under pressure to air-caster "skis", similar to how pucks are levitated above an air hockey table, while still allowing faster speeds than wheels can sustain. Hyperloop One's technology uses passive maglev for the same purpose. Linear induction motors located along the tube would accelerate and decelerate the capsule to the appropriate speed for each section of the tube route. With rolling resistance eliminated and air resistance greatly reduced, the capsules can glide for the bulk of the journey. In Musk's original Hyperloop concept, an electrically driven inlet fan and axial compressor would be placed at the nose of the capsule to "actively transfer high-pressure air from the front to the rear of the vessel", resolving the problem of air pressure building in front of the vehicle, slowing it down.[1] A fraction of the air is shunted to the skis for additional pressure, augmenting that gain passively from lift due to their shape. Hyperloop One's system does away with the compressor.

In the alpha-level concept, passenger-only pods are to be 7 ft 4 in (2.23 m) in diameter[1] and are projected to reach a top speed of 760 mph (1,220 km/h) to maintain aerodynamic efficiency.[1] (Section 4.4) The design proposes passengers experience a maximum inertial acceleration of 0.5 g, about 2 or 3 times that of a commercial airliner on takeoff and landing.

Proposed routes

number of routes have been proposed for Hyperloop systems that meet the approximate distance conditions for which a Hyperloop is hypothesized to provide improved transport times (distances of under approximately 1,500 kilometres (930 miles)).[3] Route proposals range from speculation described in company releases to business cases to signed agreements.

- United States

- The route suggested in the 2013 alpha-level design document was from the Greater Los Angeles Area to the San Francisco Bay Area. That conceptual system would begin around Sylmar, just south of the Tejon Pass, follow Interstate 5 to the north, and arrive near Hayward on the east side of San Francisco Bay. Several proposed branches were also shown in the design document, including Sacramento, Anaheim, San Diego, and Las Vegas.[1]

- No work has been done on the route proposed in Musk's alpha-design; one cited reason is that it would terminate on the fringes of the two major metropolitan areas (Los Angeles and San Francisco), resulting in significant cost savings in construction, but requiring that passengers traveling to and from Downtown Los Angeles and San Francisco, and any other community beyond Sylmar and Hayward, to transfer to another transportation mode in order to reach their final destination. This would significantly lengthen the total travel time to those destinations.[38]

- A similar problem already affects present-day air travel, where on short routes (like LAX-SFO) the flight time is only a rather small part of door to door travel time. Critics have argued that this would significantly reduce the proposed cost and/or time savings of Hyperloop as compared to the California High-Speed Rail project that will serve downtown stations in both San Francisco and Los Angeles.[39][40][41] Passengers travelling from financial center to financial center are estimated to save about two hours by taking the Hyperloop instead of driving the whole distance.[42]

- Others questioned the cost projections for the suggested California route. Some transportation engineers argued in 2013 that they found the alpha-level design cost estimates unrealistically low given the scale of construction and reliance on unproven technology. The technological and economic feasibility of the idea is unproven and a subject of significant debate.[6][7][8][38]

- In November, 2017, Arrivo announced a plan for a maglev automobile transport system from Aurora, Colorado to Denver International Airport, the first leg of a system from downtown Denver.[43] Its contract describes completion of the first leg in 2021. In February 2018, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies announced a similar plan for a loop connecting Chicago and Cleveland and a loop connecting Washington and New York City.[44]

- In 2018 the Missouri Hyperloop Coalition was formed between Virgin Hyperloop One, the University of Missouri, and engineering firm Black & Veatch to study a proposed route connecting St. Louis, Columbia, and Kansas City.[45][46]

- On December 19, 2018, Elon Musk unveiled a 2-mile (3 km) tunnel below Los Angeles. In the presentation, a Tesla Model X drove in a tunnel on the predefined track (rather than in a low-pressure tube). According to Musk the costs for the system are US$10 million.[47] Musk said: "The Loop is a stepping stone toward Hyperloop. The Loop is for transport within a city. Hyperloop is for transport between cities, and that would go much faster than 150 mph."[48]

- The Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, or NOACA, has partnered with Hyperloop Transportation Technologies to conduct a $1.3 million feasibility study for developing a Hyperloop corridor route from Chicago to Cleveland and Pittsburgh for America’s first multistate hyperloop system in the Great Lakes Megaregion. Hundreds of thousands of dollars already have been committed to the project. NOACA’s Board of Directors has awarded a $550,029 contract to Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc. (TEMS) for the Great Lakes Hyperloop Feasibility Study to evaluate the feasibility of an ultra-high-speed Hyperloop passenger and freight transport system initially linking Cleveland and Chicago.[49]

- India

- Hyperloop Transportation Technologies are in process to sign a Letter of Intent with the Indian Government for a proposed route between Chennai and Bengaluru. If things go as planned, the distance of 345 km could be covered in 30 minutes.[50] HTT also signed an agreement with Andhra Pradesh government to build India's first Hyperloop project connecting Amaravathi to Vijayawada in a 6-minute ride.

- On February 22, 2018, Hyperloop One has entered into a MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) with the Government of Maharashtra to build a hyperloop transportation system between Mumbai and Pune that would cut the travel time from the current 180 minutes to just 20 minutes.[51][52]

- Indore-based Dinclix GroundWorks' DGWHyperloop advocates a Hyperloop corridor between Mumbai and Delhi, via Indore, Kota, and Jaipur.[53]

- Elsewhere

- Many of the active Hyperloop routes being planned currently are outside of the U.S. Hyperloop One published the world's first detailed business case for a 300-mile (500 km) route between Helsinki and Stockholm, which would tunnel under the Baltic Sea to connect the two capitals in under 30 minutes.[54] Hyperloop One is also well underway on a feasibility study with DP World to move containers from its Port of Jebel Ali in Dubai.[55] Hyperloop One on November 8, 2016, announced a new feasibility study with Dubai's Roads and Transport Authority for passenger and freight routes connecting Dubai with the greater United Arab Emirates. Hyperloop One is also working on passenger routes in Moscow[56][57] and a cargo Hyperloop to connect Hunchun in north-eastern China to the Port of Zarubino, near Vladivostok and the North Korean border on Russia's Far East.[58] In May 2016, Hyperloop One kicked off their Global Challenge with a call for comprehensive proposals of hyperloop networks around the world.[59] In September 2017, Hyperloop One selected 10 routes from 35 of the strongest proposals: Toronto–Montreal, Cheyenne–Denver–Pueblo, Miami–Orlando, Dallas–Laredo–Houston, Chicago–Columbus–Pittsburgh, Mexico City–Guadalajara, Edinburgh–London, Glasgow–Liverpool, Bengaluru–Chennai, and Mumbai–Chennai.[60][61]

- Others have put forward European routes, including a route beginning at Amsterdam or Schiphol to Frankfurt proposed by Hardt Hyperloop.[62][63][64] A Warsaw University of Technology team is evaluating potential routes from Cracow to Gdańsk across Poland proposed by Hyper Poland.[65]

- TransPod is exploring the possibility of Hyperloop routes which would connect Toronto and Montreal,[66][67] Toronto to Windsor,[68] and Calgary to Edmonton.[69] Toronto and Montreal, the largest cities in Canada, are currently connected by Ontario Highway 401, the busiest highway in North America.[70] In March 2019, Transport Canada commissioned the study of the Hyperloop, so it can be “better informed on the technical, operational, economic, safety, and regulatory aspects of the Hyperloop and understand its construction requirements and commercial feasibility.”[71]

- Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT) reportedly signed an agreement with the government of Slovakia in March 2016 to perform impact studies, with potential links between Bratislava, Vienna, and Budapest, but there have been no developments on that since.[72] In January 2017, HTT signed an agreement to explore the route Bratislava—Brno—Prague in Central Europe.[73]

Open-source design evolution

In September 2013, Ansys Corporation ran computational fluid dynamics simulations to model the aerodynamics of the capsule and shear stress forces that the capsule would be subjected to. The simulation showed that the capsule design would need to be significantly reshaped to avoid creating supersonic airflow, and that the gap between the tube wall and capsule would need to be larger. Ansys employee Sandeep Sovani said the simulation showed that Hyperloop has challenges but that he is convinced it is feasible.[77][78]

In October 2013, the development team of the OpenMDAO software framework released an unfinished, conceptual open-source model of parts of the Hyperloop's propulsion system. The team asserted that the model demonstrated the concept's feasibility, although the tube would need to be 13 feet (4 m) in diameter,[79] significantly larger than originally projected. However, the team's model is not a true working model of the propulsion system, as it did not account for a wide range of technological factors required to physically construct a Hyperloop based on Musk's concept, and in particular had no significant estimations of component weight.[80]

In November 2013, MathWorks analyzed the proposal's suggested route and concluded that the route was mainly feasible. The analysis focused on the acceleration experienced by passengers and the necessary deviations from public roads in order to keep the accelerations reasonable; it did highlight that maintaining a trajectory along I-580 east of San Francisco at the planned speeds was not possible without significant deviation into heavily populated areas.[81]

In January 2015, a paper based on the NASA OpenMDAO open-source model reiterated the need for a larger diameter tube and a reduced cruise speed closer to Mach 0.85. It recommended removing on-board heat exchangers based on thermal models of the interactions between the compressor cycle, tube, and ambient environment. The compression cycle would only contribute 5% of the heat added to the tube, with 95% of the heat attributed to radiation and convection into the tube. The weight and volume penalty of on-board heat exchangers would not be worth the minor benefit, and regardless the steady-state temperature in the tube would only reach 30–40 °F (17–22 °C) above ambient temperature.[82]

According to Musk, various aspects of the Hyperloop have technology applications to other Musk interests, including surface transportation on Mars and electric jet propulsion.[83][84]

Researchers associated with MIT's department of Aeronautics and Astronautics published research in June 2017 that verified the challenge of aerodynamic design near the Kantrowitz limit that had been theorized in the original SpaceX Alpha-design concept released in 2013.[85]

In 2017, Dr. Richard Geddes and others formed the Hyperloop Advanced Research Partnership to act as a clearinghouse of Hyperloop public domain reports and data.[86]

In February 2020, Hardt Hyperloop, Hyper Poland, TransPod and Zeleros formed a consortium to drive standardisation efforts, as part of a joint technical committee (JTC20) set up by European standards bodies CEN and CENELEC to develop common standards aimed at ensuring the safety and interoperability of infrastructure, rolling stock, signalling and other systems.[87]

Mars

According to Musk, Hyperloop would be useful on Mars as no tubes would be needed because Mars' atmosphere is about 1% the density of the Earth's at sea level.[88][13][89][90] For the Hyperloop concept to work on Earth, low-pressure tubes are required to reduce air resistance. However, if they were to be built on Mars, the lower air resistance would allow a Hyperloop to be created with no tube, only a track.[91]

Hyperloop companies

Virgin Hyperloop One

Virgin Hyperloop One (formerly Hyperloop One, and before that, Hyperloop Technologies)[92][93] was incorporated in 2014 and has built a team of 280+, including engineers, technicians, welders, and machinists. It has raised more than US$160 million in capital from investors including DP World, Sherpa Capital, Formation 8, 137 Ventures, Caspian Venture Capital, Fast Digital, GE Ventures, and SNCF.

Hyperloop One was founded by Shervin Pishevar and Brogan BamBrogan.[94] BamBrogan left the company in July 2016,[95] along with three of the other founding members of Arrivo.[96] Hyperloop One then selected co-founder Josh Giegel, a former SpaceX engineer, to be CTO.[97]

Hyperloop One has a 75,000-square foot Innovation Campus in downtown LA and a 100,000-square foot machine and tooling shop in North Las Vegas. By 2017, it had completed a 500m Development Loop (DevLoop) in North Las Vegas, Nevada.[98]

On May 11, 2016, Hyperloop One conducted the first live trial of Hyperloop technology, demonstrating that its custom linear electric motor could propel a sled from 0 to 110 miles an hour in just over one second.[99] The acceleration exerted approximately 2.5 g on the sled. The sled was stopped at the end of the test by hitting a pile of sand at the end of the track, because the test was not intended to test braking components.

In July 2016, Hyperloop One released a preliminary study that suggested a Hyperloop connection between Helsinki and Stockholm would be feasible, reducing the travel time between the cities to half an hour. The construction costs were estimated by Hyperloop One to be around €19 billion (US$21 billion at 2016 exchange rates).[100]

In August 2016, Hyperloop One announced a deal with the world's third largest ports operator, DP World, to develop a cargo offloader system at DP World's flagship port of Jebel Ali in Dubai.[101] Hyperloop One also broke ground on DevLoop, its full-scale Hyperloop test track.

In November 2016, Hyperloop One disclosed that it has established a high-level working group relationship with the governments of Finland and the Netherlands to study the viability of building Hyperloop proof of operations centers in those countries. Hyperloop One also has a feasibility study underway with Dubai's Roads and Transport Authority for passenger systems in the UAE.[102] Other feasibility studies are underway in Russia, Los Angeles, and the Netherlands.

In May 12, 2017, Hyperloop One performed its first full-scale Hyperloop test, becoming the first company in the world to test a full-scale Hyperloop.[103] The system-wide test integrated Hyperloop components including vacuum, propulsion, levitation, sled, control systems, tube, and structures.

On July 12, 2017, the company revealed images of its first generation pod prototype, which will be used at the DevLoop test site in Nevada to test aerodynamics.[104]

On October 12, 2017, the company received a "significant investment" from the Virgin Group founder Richard Branson, leading to a rebrand of the name.[105]

In February 2018, Richard Branson of Virgin Hyperloop One announced that he had a preliminary agreement with the Maharashtra State government of India to build the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop.[106]

In 2019, a partnership was formed between Virgin Hyperloop One, the University of Missouri, and engineering firm Black & Veatch to investigate a Missouri Hyperloop .[45][46]

In March 2019, Missouri governor Mike Parson announced the creation of a "Blue Ribbon" panel to examine the specifics of funding and construction of the Missouri Hyperloop.[107] The route would connect Missouri's largest cites including St. Louis, Kansas City, and Columbia.[108] This comes after a 2018 feasibility study found the route viable, the first such study in the United States.[109]

In June 2019, a partnership with the Sam Fox School of Washington University of St. Louis was announced to further investigate different proposals for the Missouri Hyperloop.[110]

In July 2019, the Government of Maharashtra and Hyperloop One set a target to create the first hyperloop system in the world between Pune and Mumbai.

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies

Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT) is the first Hyperloop company created (founded in 2013), with a current workforce of more than 800 engineers and professionals located around the world.[111] Some collaborate part-time; others are full-time employees and contributors. Some members are full-time paid employees; others work in exchange for salary and stock options.[112]

After Musk's Hyperloop concept proposal in 2012, Jumpstarter, Inc founder Dirk Ahlborn placed a 'call to action' on his Jumpstarter platform.[113] Jumpstarter started pooling resources and amassed 420 people to the team.[113]

HTT announced in May 2015 that a deal had been finalized with landowners to build a 5-mile (8 km) test track along a stretch of road near Interstate 5 between Los Angeles and San Francisco.[114] In December 2016, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies and the government of Abu Dhabi announced plans to conduct a feasibility study on a Hyperloop link between the UAE capital and Al Ain, reducing travel time between Abu Dhabi and Al Ain to just under 10-minutes.[115] In September 2017, HTT announced and signed an agreement with the Andhra Pradesh state government of India to build a track from Amaravathi to Vijayawada in a public-private partnership, and suggested that the more than one hour trip could be reduced to 5 minutes through the project.[116][117] For yet undisclosed reason, neither the test track that HTT announced in May 2015 nor any other test track has been built in the last 3 years.

In June 2018, Ukraine's Infrastructure Ministry reached an agreement with Hyperloop Transportation Technologies to develop its high-speed vacuum transport technology in Ukraine.[118] According to minister, Volodymyr Omelyan, a joint research and development center will be created in Kyiv or Dnipro, which will not only work on Hyperloop but new “materials and components for modern transportation systems.”[118]

Later in 2018, the company signed an agreement with the Guizhou province of China to build a Hyperloop.[119] In its China deal, HTT will provide technology, engineering expertise, and essential equipment in the venture, while Tongren will take charge of relevant certifications, regulatory framework, and construction of the system, the press release said. The venture will be a public private partnership in which 50 percent of the funds will come directly from Tongren, it added.[119]

In May 2019, the company and TÜV SÜD presented the EU with generic guidelines for hyperloop design, operation and certification.[120] In June 2019,Hyperloop Transportation Technologies met with officials from the United States Department of Transportation, USDOT, at HyperloopTT's research facilities in Toulouse, France.[121] Simultaneously, other members of HyperloopTT met with the USDOT at the agency's offices in Washington D.C. presenting a technical overview of Hyperloop technology and the certification guideline completed by TÜV SÜD.[121]

HyperloopTT is now beginning the process of integrating their full-scale passenger capsule for human trials in 2020.[121]

TransPod

TransPod Inc. is a Canadian company designing and manufacturing ultra-high-speed tube transportation technology and vehicles.[122] In November 2016 TransPod raised a US$15 million seed round from Angelo Investments, an Italian high-tech holding group, specializing in advanced technologies for the railway, space, and aviation industries.[123]

In September 2017, TransPod released a scientific peer-reviewed publication in the journal Procedia Engineering.[124] The paper was premiered at the EASD EURODYN 2017 conference,[125] and presents the physics of the TransPod system.[126]

TransPod vehicles are being designed to travel at over 1,000 km/h between cities using fully electric propulsion and zero need for fossil fuels.[126] The TransPod tube system is distinct from the hyperloop concept proposed by Elon Musk's Hyperloop Alpha white paper. The TransPod system uses moving electromagnetic fields to propel the vehicles with stable levitation off the bottom surface, rather than compressed air.[126] TransPod is stated to contain further developments beyond hyperloop.[127][128] To achieve fossil-fuel-free propulsion, TransPod "pods" take advantage of electrically-driven linear induction motor technology, with active real-time control[126] and sense-space systems.[129] The cargo transport TransPod pods will be able to carry payloads of 10–15 tons and have compatibility with wooden pallets, as well as various unit load devices such as LD3 containers, and AAA containers.[130]

At the InnoTrans Rail Show 2016 in Berlin, TransPod premiered their vehicle concept, alongside implementation of Coelux technology—an artificial skylight to emulate natural sunlight within the passenger pods.[131][132]

TransPod has partnered with investor Angelo Investments' member companies MERMEC, SITAEL, and Blackshape Aircraft. With international staff of over 1,000 employees, 650 of whom are engineers, they will collaborate with the development and testing of the TransPod tube system[133][134][123] It has since expanded from its Toronto, Canada headquarters at MaRS Discovery District[135][136] to open offices in Toulouse, France and Bari, Italy.[137][138] TransPod is additionally partnered with university researchers, engineering firm IKOS,[139] REC Architecture and Liebherr-Aerospace.[140][141][142]

TransPod is developing routes worldwide and in Canada such as Toronto-Montreal,[143][67][144] Toronto-Windsor,[68] and Calgary-Edmonton.[69] TransPod is preparing to build a test track for the pod vehicles in Canada.[145] This track will be extendable as part of a full route pending a combination of private and public funding to construct the line.[69]

In July 2017, TransPod released an initial cost study[146] which outlines the viability of building a hyperloop line in Southwestern Ontario between the cities of Windsor and Toronto.[147] The study indicates a TransPod tube system would cost half the projected cost of a high-speed rail line along the same route, while operating at more than four times the top speed of high speed rail.[146]

TransPod has announced plans for a test track to be constructed in the town of Droux near Limoges[148] in collaboration with the French department of Haute-Vienne. The proposed test track would exceed 3 km in length, and operate as a half-scale system 2 m in diameter.[149][150][151] In February 2018 Vincent Leonie, vice president of Limoges Métropole and a deputy mayor of Limoges,[152] has announced agreements for the "Hyperloop Limoges" organization have been signed to promote and accelerate the technology.[149]

DGWHyperloop

Established in 2015, DGWHyperloop is a subsidiary of Dinclix GroundWorks, an engineering company based in Indore, India.[153] DGWHyperloop's initial proposals include a Hyperloop-based corridor between Delhi and Mumbai called the Delhi Mumbai Hyperloop Corridor (DMHC).[154][155] The company has partnered with many government agencies, private companies, and institutions for its research on Hyperloop.[156] DGWHyperloop is the only Indian company working on implementing the Hyperloop system across the nation.[157][158][159]

Arrivo

Arrivo was a technology architecture and engineering company founded in Los Angeles in 2016.[160] In November 2017, it disclosed a plan to build a 200 mph (320 km/h) link for automobiles to Denver International Airport using maglev train technology by 2021.[43] On December 14, 2018 Technology news site The Verge reported Arrivo was shutting down, due to being unable to secure Series A funding.[161]

Hardt Global Mobility

Hardt Global Mobility[162] was founded in 2016 in Delft, emerging from the TU Delft Hyperloop team who won at the SpaceX Pod Competition.[28]

The Dutch team is setting up a full-scale testing center for hyperloop technology in Delft. Hardt has received over €600,000 in funding for the initial rounds of testing, with plans to raise more to build a high-speed test line by 2019.[163] At the unveiling of the test track, Dutch Minister of Infrastructure and Environment Schultz van Haegen said a Hyperloop system could help cement the Netherlands' position as a gateway to Europe by transporting freight arriving at Rotterdam's sprawling port.[164]

In October 9, 2017 a report was released with information from Hardt Global Mobility and Hyperloop One. The report has been sent to the Dutch House of Representatives and judges the added value of a hyperloop test track facility. The report recommends building a test track of 5 km in Flevoland.[165]

Hyper Chariot

Hyper Chariot is a startup company based in Santa Monica, United States, that promoted itself from May to July 2017. The company has an ambitious plan.[166] On July 27, 2017 it announced a partnership with AML Superconductivity and Magnetics for the development of the vehicle and related propulsion system.[167]

Zeleros

Zeleros[168][169] was founded in Valencia (Spain) in November 2016 by Daniel Orient (CTO), David Pistoni (CEO) and Juan Vicén (CMO), former leaders of the Hyperloop UPV team from Universitat Politècnica de València. The team was awarded "Top Design Concept" and "Propulsion/Compression Subsystem Technical Excellence" at SpaceX's Hyperloop Design Weekend, the first phase of the Hyperloop Pod Competition conducted at Texas A&M University on January 29–30, 2016.[170] After building Spain's first Hyperloop prototype with the support of Purdue University[171] and building a 12-meter research test-track in Spain[172] at the university, the company was awarded in November 2017 the international Everis Foundation prize.[173] Zeleros has the support of the Silicon Valley accelerator Plug and Play Tech Center, its partner Alberto Gutierrez, (partner of Plug and Play Spain and founder of Aqua Service), and the Spanish venture capital fund Angels Capital owned by the Spanish businessman Juan Roig, owner of Mercadona. By June 2018, the corporation signed an agreement with the rest of the Hyperloop European companies (Hyper Poland and Hardt) and the Canadian TransPod to collaborate with the European Union and other international institutions for the implementation of a definition of the standards to ensure the interoperability and the security of a Hyperloop. In August 2018, Zeleros held a meeting with Pedro Duque, the ministry of science to push for his support of the European initiative. By September 2018, the corporation announced the construction of a 2 km test track to perform dynamic tests of the system. The test track will be allocated in Sagunto in 2019 with the support of the Sagunto council and the Generalitat Valenciana. In November 2018, Zeleros received the international award in the World Transport Congress in Mascate, Omán.[174] By February 2019, the corporation was formed by a team of 20 engineers and doctors specialized in different fields, developing and testing the systems and subsystems of the Hyperloop integrators.

In June 2020 Zeleros raised more than €7 million in financing, with plans to use them in the development of it's core technologies, the construction of a European Hyperloop Development Centre in Spain and building a 3 km test track. [175]

Hyper Poland

Hyper Poland[65] is a Polish company founded in 2017 by engineers who graduated from the Warsaw University of Technology. In the summer of 2017, acting as the Hyper Poland University Team, they built a hyperloop model which took part in the SpaceX Pod Competition II in California. In March 2018, the company was recognized as one of the best startups in the mobility sector in Europe.[176]

Hyperloop pod competition

A number of student and non-student teams were participating in a Hyperloop pod competition in 2015–16, and at least 22 of them built hardware to compete on a sponsored hyperloop test track in mid-2016.[177]

In June 2015, SpaceX announced that they would sponsor a Hyperloop pod design competition, and would build a 1-mile-long (1.6 km) subscale test track near SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California for the competitive event in 2016.[178][179] SpaceX stated in their announcement, "Neither SpaceX nor Elon Musk is affiliated with any Hyperloop companies. While we are not developing a commercial Hyperloop ourselves, we are interested in helping to accelerate development of a functional Hyperloop prototype."[180]

More than 700 teams had submitted preliminary applications by July,[181] and detailed competition rules were released in August.[182] Intent to Compete submissions were due in September 2015 with more detailed tube and technical specification released by SpaceX in October. A preliminary design briefing was held in November 2015, where more than 120 student engineering teams were selected to submit Final Design Packages due by January 13, 2016.[183]

A Design Weekend was held at Texas A&M University January 29–30, 2016, for all invited entrants.[184] Engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were named the winners of the competition. While the University of Washington team won the Safety Subsystem Award, Delft University won the Pod Innovation Award[185] as well as the second place, followed by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Virginia Tech, and the University of California, Irvine.[177][186] In the Design Category, the winner team was Hyperloop UPV from Universitat Politecnica de Valencia, Spain.[187] On January 29, 2017, Delft Hyperloop (Delft University of Technology) won the prize for the "best overall design" at the final stage of the SpaceX Hyperloop competition,[188] while WARR Hyperloop of the Technical University of Munich won the prize for "fastest pod".[29] The Massachusetts Institute of Technology placed third.[189]

The second Hyperloop pod competition took place from August 25–27, 2017. The only judging criteria being top speed provided it is followed by successful deceleration. WARR Hyperloop from the Technical University of Munich won the competition by reaching a top speed of 324 km/h (201 mph).[32][33][34]

A third Hyperloop pod competition took place in July 2018. The defending champions, the WARR Hyperloop team from the Technical University of Munich, beat their own record with a top speed of 457 km/h (284 mph) during their run.[35] The fourth competition in August 2019 saw the team from the Technical University of Munich, now known as TUM Hyperloop (by NEXT Prototypes e.V.),[36] again winning the competition and beating their own record with a top speed of 463 km/h (288 mph).[29]

Criticism and human factor considerations

Some critics of Hyperloop focus on the experience—possibly unpleasant and frightening—of riding in a narrow, sealed, windowless capsule inside a sealed steel tunnel, that is subjected to significant acceleration forces; high noise levels due to air being compressed and ducted around the capsule at near-sonic speeds; and the vibration and jostling.[190] Even if the tube is initially smooth, ground may shift with seismic activity. At high speeds, even minor deviations from a straight path may add considerable buffeting.[191] This is in addition to practical and logistical questions regarding how to best deal with safety issues such as equipment malfunction, accidents, and emergency evacuations.

Other maglev trains are already in use, which avoid much of the added costs of Hyperloop. The SCMaglev[192] in Japan has demonstrated 603 km/h (375 mph) without a vacuum tube, by using an extremely aerodynamic train design. It also avoids the cost and time required to pressurize and depressurize the exit and entry points of a Hyperloop tube.

There is also the criticism of design technicalities in the tube system. John Hansman, professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, has stated problems, such as how a slight misalignment in the tube would be compensated for and the potential interplay between the air cushion and the low-pressure air. He has also questioned what would happen if the power were to go out when the pod was miles away from a city. UC Berkeley physics professor Richard Muller has also expressed concern regarding "[the Hyperloop's] novelty and the vulnerability of its tubes, [which] would be a tempting target for terrorists", and that the system could be disrupted by everyday dirt and grime.[193]

Political and economic considerations

The alpha proposal projected that cost savings compared with conventional rail would come from a combination of several factors. The small profile and elevated nature of the alpha route would enable Hyperloop to be constructed primarily in the median of Interstate 5. However, whether this would be truly feasible is a matter of debate. The low profile would reduce tunnel boring requirements and the light weight of the capsules is projected to reduce construction costs over conventional passenger rail. It was asserted that there would be less right-of-way opposition and environmental impact as well due to its small, sealed, elevated profile versus that of a rail easement;[1] however, other commentators contend that a smaller footprint does not guarantee less opposition.[38] In criticizing this assumption, mass transportation writer Alon Levy said, "In reality, an all-elevated system (which is what Musk proposes with the Hyperloop) is a bug rather than a feature. Central Valley land is cheap; pylons are expensive, as can be readily seen by the costs of elevated highways and trains all over the world".[194][195] Michael Anderson, a professor of agricultural and resource economics at UC Berkeley, predicted that costs would amount to around US$100 billion.[7]

The Hyperloop white paper suggests that US$20 of each one-way passenger ticket between Los Angeles and San Francisco would be sufficient to cover initial capital costs, based on amortizing the cost of Hyperloop over 20 years with ridership projections of 7.4 million per year in each direction and does not include operating costs (although the proposal asserts that electric costs would be covered by solar panels). No total ticket price was suggested in the alpha design.[1] The projected ticket price has been questioned by Dan Sperling, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis, who stated that "there's no way the economics on that would ever work out."[7]

The early cost estimates of the Hyperloop are a subject of debate. A number of economists and transportation experts have expressed the belief that the US$6 billion price tag dramatically understates the cost of designing, developing, constructing, and testing an all-new form of transportation.[6][7][38][195] The Economist said that the estimates are unlikely to "be immune to the hypertrophication of cost that every other grand infrastructure project seems doomed to suffer."[196]

Political impediments to the construction of such a project in California will be very large. There is a great deal of "political and reputation capital" invested in the existing mega-project of California High-Speed Rail.[196] Replacing that with a different design would not be straightforward given California's political economy. Texas has been suggested as an alternate for its more amenable political and economic environment.[196]

Building a successful Hyperloop sub-scale demonstration project could reduce the political impediments and improve cost estimates. Musk has suggested that he may be personally involved in building a demonstration prototype of the Hyperloop concept, including funding the development effort.[15][196]

The solar panels Musk plans to install along the length of the Hyperloop system have been criticized by engineering professor Roger Goodall of Loughborough University, as not being feasible enough to return enough energy to power the Hyperloop system, arguing that the air pumps and propulsion would require much more power than the solar panels could generate.[193]

Related projects

Historical

The concept of transportation of passengers in pneumatic tubes is not new. The first patent to transport goods in tubes was taken out in 1799 by the British mechanical engineer and inventor George Medhurst. In 1812, Medhurst wrote a book detailing his idea of transporting passengers and goods through air-tight tubes using air propulsion.[197]

In the early 1800s, there were other similar systems proposed or experimented with and were generally known as an atmospheric railway although this term is also used for systems where the propulsion is provided by a separate pneumatic tube to the train tunnel itself.

One of the earliest was the Dalkey Atmospheric Railway which operated near Dublin between 1844 and 1854.

The Crystal Palace pneumatic railway operated in London around 1864 and used large fans, some 22 ft (6.7 m) in diameter, that were powered by a steam engine. The tunnels are now lost but the line operated successfully for over a year.

Operated from 1870 to 1873, the Beach Pneumatic Transit was a one-block-long prototype of an underground tube transport public transit system in New York City. The system worked at near-atmospheric pressure, and the passenger car moved by means of higher-pressure air applied to the back of the car while somewhat lower pressure was maintained on the front of the car.[198]

In the 1910s, vacuum trains were first described by American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard.[196] While the Hyperloop has significant innovations over early proposals for reduced pressure or vacuum-tube transportation apparatus, the work of Goddard "appears to have the greatest overlap with the Hyperloop".[5]

In 1981 Princeton Physicist Gerard K. O'Neill wrote about transcontinental trains using magnetic propulsion in his book 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future. While a work of fiction, this book was an attempt to predict future technologies in everyday life. In his prediction, he envisioned these trains which used magnetic levitation running in tunnels which had much of the air evacuated to increase speed and reduce friction. He also demonstrated a scale prototype device that accelerated a mass using magnetic propulsion to high speeds. It was called a mass driver and was a central theme in his non-fiction book on space colonization "The High Frontier".

Swissmetro was a proposal to run a maglev train in a low-pressure environment. Concessions were granted to Swissmetro in the early 2000s to connect the Swiss cities of St. Gallen, Zurich, Basel, and Geneva. Studies of commercial feasibility reached differing conclusions and the vactrain was never built.[199]

China was reported to be building a vacuum based 600 mph (1,000 km/h) maglev train in August 2010 according to a laboratory at Jiaotong University. It was expected to cost CN¥10–20 million (US$2.95 million at the August 2010 exchange rate) more per kilometer than regular high-speed rail.[200] As of May 2017, it has not been built.

Current

The ET3 Global Alliance (ET3) was founded by Daryl Oster in 1997 with the goal of establishing a global transportation system using passenger capsules in frictionless maglev full-vacuum tubes. Oster and his team met with Elon Musk on September 18, 2013, to discuss the technology,[201] resulting in Musk promising an investment in a 3-mile (5 km) prototype of ET3's proposed design.[202]

See also

References

- Musk, Elon (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop Alpha" (PDF). SpaceX. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- Opgenoord, Max M. J. "How does the aerodynamic design implement in hyperloop concept?". Mechanical Engineering. MIT - Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Ranger, Steve. "What is Hyperloop? Everything you need to know about the race for super-fast travel". ZDNet. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Pando Monthly presents a fireside chat with Elon Musk". pando.com. PandoDaily. July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Beyond the hype of Hyperloop: An analysis of Elon Musk's proposed transit system". Gizmag.com. August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- Bilton, Nick. "Could the Hyperloop Really Cost $6 Billion? Critics Say No". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- Brownstein, Joseph (August 14, 2013). "Economists don't believe the Hyperloop". Al Jazeera America.

- Melendez, Eleazar David (August 14, 2013). "Hyperloop Would Have 'Astronomical' Pricing, Unrealistic Construction Costs, Experts Say". The Huffington Post.

- Hawkins, Andrew J. (June 18, 2016). "Here are the Hyperloop pods competing in Elon Musk's big race later this year". The Verge. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- Etherington, Darrell (September 2, 2016). "Here's a first look at the SpaceX Hyperloop test track". TechCrunch.

- . TechCrunch. September 2, 2016 https://qz.com/india/1679458/richard-bransons-virgin-hyperloop-one-project-gets-nod-in-india/#:~:text=India%20is%20officially%20getting%20serious,which%20is%20200%20kilometres%20away.&text=A%20hyperloop%20is%20an%20ultra,system%20akin%20to%20bullet%20trains. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Pensky, Nathan; Lacy, Sarah; Musk, Elon (July 12, 2012). PandoMonthly Presents: A Fireside Chat with Elon Musk. PandoDaily/YouTube.com. Event occurs at 43:13. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- Elon Musk speaks at the Hyperloop Pod Award Ceremony. YouTube.com. January 30, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Gannes, Liz (May 30, 2013). "Tesla CEO and SpaceX Founder Elon Musk: The Full D11 Interview (Video)". All Things Digital. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "Musk announces plans to build Hyperloop demonstrator". Gizmag.com. August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- Musk, Elon (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop". Tesla. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- Flankl, Michael; Wellerdieck, Tobias; Tüysüz, Arda; Kolar, Johann W. (November 2017). "Scaling laws for electrodynamic suspension in high-speed transportation" (PDF). IET Electric Power Applications. 12 (3): 357–364. doi:10.1049/iet-epa.2017.0480. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Energy Efficiency of an Electrodynamically Levitated Hyperloop Pod. Energy Science Center. November 29, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Mendoza, Martha (August 12, 2013). "Elon Musk to reveal mysterious 'Hyperloop' high-speed travel designs Monday". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- "Word Mark HYPERLOOP". U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Muoio, Danielle (August 17, 2017). "Everything we know about Elon Musk's ambitious Hyperloop plan". Business Insider. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Wattles, Jackie (June 15, 2015). "SpaceX to hold Hyperloop competition". CNN Money. CNN.

- Baker, David R. (June 15, 2015). "Build your own hyperloop! SpaceX announces pod competition". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Chee, Alexander (November 30, 2015). "The Race to Create Elon Musk's Hyperloop Heats Up". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Lee, Dave (May 14, 2016). "Magnetic Hyperloop pod unveiled at MIT". BBC. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Zimmerman, Leda (February 1, 2016). "MIT students win first round of SpaceX Hyperloop contest". Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Hyperloop, MIT (January 30, 2017). "MIT Hyperloop Flight Jan 29th 2017 - First Ever Low Pressure Hyperloop Run". Youtube. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Pieters, Janene (January 30, 2017). "Delft students win Elon Musk's hyperloop competition". NL Times. The Netherlands. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- "Hyperloop". SpaceX. June 8, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "Students from Munich in the final round of SpaceX Hyperloop Competition" (PDF) (Press release). February 5, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- "Here are the big winners of Elon Musk's Hyperloop pod competition". Business Insider Deutschland (in German). Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- "Student group from Technical University of Munich sets new Hyperloop speed record and wins second SpaceX Pod Competition" (PDF) (Press release). August 28, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- "Hyperloop One Goes Farther and Faster Achieving Historic Speeds". Hyperloop One. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- "Here are the big winners from Elon Musk's Hyperloop competition". Business Insider. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- Hawkins, Andrew J. (July 22, 2018). "WARR Hyperloop pod hits 284 mph to win SpaceX competition". The Verge. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "TUM Hyperloop by NEXT Prototypes e.V." Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- De Chant, Tim (August 13, 2013). "Promise and Perils of Hyperloop and Other High-Speed Trains". PBS.org. Nova Next. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- Johnson, Matt (August 14, 2013). "Musk's Hyperloop math doesn't add up". Greater Greater Washington.

- Levy, Alon (August 13, 2013). "Loopy Ideas Are Fine, If You're an Entrepreneur". Pedestrian Observations. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Sinclair, James (August 12, 2013). "Hyperloop proposal: Bad joke or attempt to sabotage California HSR project?". Stop and Move. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Johnson, Matt (August 14, 2013). "Musk's Hyperloop math doesn't add up". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Humphreys, Pat (March 23, 2016). "Pipedreams". Transport and Travel. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- Jenkins, Aric (November 14, 2017). "A Guy Named Brogan BamBrogan Wants to Bring a 200 mph Hyperloop to Denver. Here's His Plan". Fortune. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Bauer, Meredith Rutland (February 23, 2018). "Who's Ready to Hyperloop to Cleveland?". CityLab. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- "Missouri Is One Step Closer to a Hyperloop with In-Depth Feasibility Study". hyperloop-one.com. Virgin Hyperloop One. January 30, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Knapp, Alex (January 30, 2018). "Plans Are Moving Forward To Bring A Hyperloop Route To Missouri". forbes.com. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- WELT (December 19, 2018). ""Loop"-Projekt: Mit nur 80 km/h durch Elons Musks Turbo-Tunnel". DIE WELT. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- Walker, Alissa (December 18, 2018). "Here's what it's like to ride in Elon Musk's tunnel". Curbed LA. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Hyperloop could bring new options".

- technology, BENGALURU (December 7, 2016). "India in talks to build Hyperloop; two Indian companies involved in the project". ET online. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- "Mumbai-Pune 25-minute Hyperloop ride by 2024 could be a pipe dream". Moneycontrol.

- "Brinkwire". en.brinkwire.com.

- "DGWHyperloop - Overview" (PDF). October 29, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- "Hyperloop One, FS Links And KPMG Publish World's First Study Of Full Scale Hyperloop System". PR Newswire. July 5, 2016.

- "Hyperloop One gets $50 million in funding led by Dubai's DP World Group, one of the world's largest ports operators". LA Times. October 12, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- "0 to 400mph in 2 seconds? Russian Railways eyes supersonic Hyperloop technology". RT. May 19, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- "Russland plant Hyperloop-Strecke zwischen Moskau und Sankt Petersburg". Deutsche Wirtschafts Nachrichten. June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- "Hyperloop One Can Open Up Russia's Far East to China Trade | Hyperloop One". Hyperloop One. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- "Hyperloop One Global Challenge". Hyperloop One. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Todd, Jeff (September 14, 2017). "Hyperloop Becomes Closer To Reality In Colorado". CBS4. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- "Hyperloop One Global Challenge Winners". Hyperloop One. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Eldering, Paul (April 17, 2019). "Hyperloop krijgt vleugels: Schiphol - Frankfurt in halfuur" [Hyperloop develops wings: Schiphol - Frankfurt in half an hour]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). The Netherlands. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- van Miltenburg, Olaf (January 23, 2016). "TU Delft onthult Hyperloop-ontwerp - Vervoermiddel van de toekomst" [TU Delft unveils Hyperloop design - Means of transport of the future]. Tweakers.net (in Dutch). Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "Delft Hyperloop - Revealing the Future of Transportation". YouTube.com. January 22, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Wedziuk, Emilia (February 17, 2016). "Hyperloop made in Poland gets more and more realistic". ITkey Media (in Polish). Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Bambury, Brent (September 16, 2016). "Toronto to Montreal in less than 30 minutes? How a Canadian company plans to make it happen". CBC Radio. Canada. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- "Rapid Transit". CBC. CBC. September 18, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Aboelsaud, Yasmin (July 26, 2017). "Toronto tech company proposes Toronto-Windsor hyperloop connection". Daily Hive. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Calgary to Edmonton in 30 minutes? Hyperloop could be the future of transportation in Alberta". CBC. CBC. April 7, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "The Busiest Highway in North America". Opposite Lock. US. April 6, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- Aboelsaud, Yasmin (April 4, 2019). "Virgin Hyperloop One: New transit technology could be here in years not decades". Daily Hive. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Guerrini, Federico (March 10, 2016). "Crowdsourced Hyperloop Venture Inks A Deal With... Bratislava?". Forbes. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- Buhr, Sarah (January 18, 2017). "Hyperloop Transportation Technologies plans to connect all of Europe, starting with the Czech Republic". TechCrunch. US. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- "Sintef vil teste hyperloop for laks" [Sintef will test the hyperloop for salmon]. Dagens Næringsliv AS (in Norwegian). Norway. December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Madslien, Jørn (July 19, 2017). "Investment in hyperloop routes speeds up". UK: Institute of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- Davies, Alex (June 20, 2017). "South Korea Is Building a Hyperloop". Wired. US. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- Danigelis, Alyssa (September 20, 2013). "Hyperloop Simulation Shows It Could Work". Discovery News. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- Statt, Nick (September 19, 2013). "Simulation verdict: Elon Musk's Hyperloop needs tweaking". CNET News. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- "Hyperloop in OpenMDAO". OpenMDAO. October 9, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- "Future Modeling Road Map". OpenMDAO. October 9, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- "Hyperloop: Not So Fast". MathWorks. November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Chin, Jeffrey C.; Gray, Justin S.; Jones, Scott M.; Berton, Jeffrey J. (January 2015). Open-Source Conceptual Sizing Models for the Hyperloop Passenger Pod (PDF). 56th AIAA/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference. January 5–9, 2015. Kissimmee, Florida. doi:10.2514/6.2015-1587.

- Morris, David Z. (January 31, 2016). "MIT Wins Hyperloop Competition, And Elon Musk Drops In". Fortune. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- Musk, Elon (January 30, 2016). Elon Musk speaks at the Hyperloop Pod Award Ceremony. YouTube.com. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Opgenoord, Max M. J.; Caplan, Philip C. (June 5, 2017). On the Aerodynamic Design of the Hyperloop Concept (PDF). 35th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference. US: AIAA. doi:10.2514/6.2017-3740.

- Egli, Dane (July 31, 2017). "Hyperloop will improve transportation and national security". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- D'Silva, Krishtina (February 13, 2020). "European countries to set up JTC20 to regulate hyperloop travel systems". Urban Transport News.

- Williams, Matt (July 3, 2017). "Mars Compared to Earth". Universe Today. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Vanstone, Leon (July 13, 2015). "Elon Musk's high-speed Hyperloop train makes more sense for Mars than California". The Conversation. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Muoio, Danielle (February 6, 2016). "Elon Musk talks Hyperloop on Mars". Tech Insider. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Williams, Matt (February 12, 2016). "Musk Says Hyperloop Could Work On Mars... Maybe Even Better!". Universe Today. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Deep in the Desert, Richard Branson Is Bringing the Hyperloop to Life". Wired. January 13, 2018.

- Fitzpatrick, Alex (May 10, 2016). "The Race to Build the Hyperloop Just Got Real". Time Magazine. United States. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Hyperloop Is Real: Meet The Startups Selling Supersonic Travel". forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- "Ousted Hyperloop One co-founder Brogan BamBrogan is suing Shervin Pishevar, claims harrassment [sic]". Techcrunch. Techcrunch. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Arrivo arrives as a new Hyperloop venture from a Hyperloop One co-founder". Techcrunch. Techcrunch. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Hyperloop One Replaces Co-Founder Brogan BamBrogan with Senior Vice President of Engineering Josh Giegel". wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Photos: Hyperloop One Shows Off 'DevLoop' Test Tube in Nevada". Inverse. March 7, 2017.

- Fallon, Dan (May 11, 2016). "Watch The First Real-World Test Of Hyperloop Technology". Digg. US. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Hawkins, Andrew J. (July 5, 2016). "Hyperloop One says it can connect Helsinki to Stockholm in under 30 minutes". The Verge. US. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- One, Hyperloop. "Hyperloop One, DP World Sign Agreement To Pursue A Hyperloop Route In Dubai". www.prnewswire.com.

- Kharpal, Arjun (November 10, 2016). "Hyperloop One explores setting up high-speed transport system in Finland, Netherlands, Dubai". CNBC. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- "Hyperloop's first real test is a whooshing success". Wired. July 12, 2017.

- Walker, Alissa (July 12, 2017). "Hyperloop One reveals full-size prototype of its shiny new pod design". Curbed.

- Branson, Richard (October 12, 2017). "Introducing Virgin Hyperloop One – the world's most revolutionary train service". Virgin. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- Sommerlad, Joe (February 19, 2018). "Virgin to build super-fast Hyperloop shuttle between Pune and Mumbai as India ramps up infrastructure spending". The Independent. UK. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- McKinley, Edward (March 12, 2019). "Kansas City-St. Louis Hyperloop on a fast track? New panel to look for funding". kansascity.com. Kansas City Star. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- della Cava, Marco (January 30, 2018). "Is Missouri ready for 700 mph hyperloop commutes?". usatoday.com. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Edelstein, Stephen (January 31, 2018). "Missouri May Get Its Own Hyperloop If It Isn't Two Expensive". thedrive.com. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Designing hyperloop infrastructure | The Source | Washington University in St. Louis". The Source. June 24, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Insider, Cadie Thompson, Business. "A company that wants to build a real Hyperloop just revealed details about its next big move". Business Insider. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "Company offers Nasa scientists and experts a piece of the business to deliver Hyperloop". The National. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "The future of transportation? A chat with Hyperloop's CEO". Tech.eu. October 16, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Roberts, Daniel (May 20, 2015). "Elon Musk's craziest project is coming closer to reality". Fortune. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- "Abu Dhabi explores Hyperloop link with Al Ain, potentially transforming cruise tourism in the city". Cruise Arabia & Africa. December 12, 2016.

- Satyanarayan Iyer (September 6, 2017). "First Hyperloop in India to be launched between Amravati and Vijayawada". The Times of India. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ET Bureau (September 6, 2017). "Amaravati to Vijayawada in 5 minutes! This is what hyperloop can do for you". The Economic Times. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- "Infrastructure Ministry promises to launch Hyperloop in Ukraine in 5 years | KyivPost - Ukraine's Global Voice". KyivPost. June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Tan, Huileng (July 20, 2018). "China looks to the future of transportation with new hyperloop deal". CNBC. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "Hyperloop TT outlines how it should be regulated in Europe". Engadget. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "Hyperloop reveals new guidelines - The Medi Telegraph". www.themeditelegraph.com. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "About TransPod". TransPod. TransPod Inc. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "TransPod Raises $15 Million Seed Round to Commercialize Hyperloop Travel". TechVibes. November 23, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Janzen, Ryan (2017). "Trans Pod Ultra-High-Speed Tube Transportation: Dynamics of Vehicles and Infrastructure". Procedia Engineering. 199: 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.142.

- "Keynote Lectures – Eurodyn". Eurodyn 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Janzen, Ryan (2017). "TransPod Ultra-High-Speed Tube Transportation: Dynamics of Vehicles and Infrastructure" (PDF). Procedia Engineering. 199: 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.142. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Janzen, Ryan. "The future of transportation". YouTube. TEDx Toronto. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Galang, Jessica. "TransPod raises $20 million seed round to continue hyperloop development". BetaKit. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Janzen, R; Mann, S (2016). "The Physical-Fourier-Amplitude Domain, and Application to Sensing Sensors". Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia.

- "PARIS AIR FORUM – Intervention de Sebastien Gendron – TransPod Hyperloop". TVLaTribune. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via YouTube.

- "This Canadian Hyperloop Concept Features a Faux Sunroof". WIRED. October 4, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Wood, Eric. "Toronto startup's hyperloop technology makes a splash at Berlin trade show". itbusiness.ca. itbusiness.ca.

- "MERMEC joins Transpod Inc. in hyperloop system development". MERMEC. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Sitael joins TransPod Inc. in hyperloop system development". SITAEL. November 23, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "TransPod Inc. - MaRS". MaRS. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "TransPod Accelerates Global Growth with Opening of Three Offices in North America and Europe". Mass Transit. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "TransPod Accelerates Growth Opening Three Global Offices". Blackshape Aircraft. March 15, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Brown, Mike (March 15, 2017). "TransPod Wants to Develop a Hyperloop for Canada by 2020". Inverse. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "TransPod partners with IKOS on design of hyperloop pod". Canadian Green Tech. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Lewis, Rob. "TransPod Partners with Liebherr-Aerospace to Develop Technology for Hyperloop". Techvibes. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Sebastian Sjöberg (March 23, 2016). "Hyperloop Makers interview: Transpod, an infrastructure startup". 10X Labs. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- Evan Pang (March 15, 2016). "Canadian Tech Company Designing A Pod That Travels 600 KM Per Hour". The Huffington Post Canada. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- "Hyperloop: The tube that promises to get you from Montreal to Toronto in less than 30 minutes". Toronto Star. March 13, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- "Toronto-Montreal Hyperloop plan could see travel time cut to 39 minutes View description Share". The Morning Show. September 18, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Thomas, Brodie. "Hyperloop startup TransPod scouting Alberta for test track options". Metro News. Metro News. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "INITIAL ORDER OF MAGNITUDE ANALYSIS FOR TRANSPOD HYPERLOOP SYSTEM INFRASTRUCTURE" (PDF). TransPod. TransPod. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Kowlton, Thomas (July 13, 2017). "Hype for Hyperloop in Canada: Half the Cost, Quadruple the Speed of Proposed High-Speed Rail Plan". Techvibes. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Une piste pour l'Hyperloop à l'étude au nord de la Haute-Vienne". Le Populaire. January 25, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- Chapperon, Olivier (February 20, 2018). "Première esquisse pour la piste d'essai de l'hyperloop en Haute-Vienne". Le Populaire. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "Limoges-Paris en 40 minutes". 20 Heures. January 25, 2018.

- Gradt, Jean Michel (February 27, 2018). "Train supersonique: HyperloopTT prend de l'avance En savoir plus sur". Les Echos. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "Les élus". Limoges Metropole. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "DGWHyperloop - Overview" (PDF). Dinclix GroundWorks R&D. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Delhi-Mumbai Hyperloop Corridor". DGWHyperloop. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Proposed Hyperloop Project between Delhi and Mumbai". The Hans India. January 18, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Support Us - DGWHyperloop". DGWHyperloop. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Hyperloop Technology Global Market Outlook 2017-2023". Business Insider. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Hyperloop Technology Market to Reach $1.3 Billion by 2022 - Key Players are Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, Hyperloop One, DGWHyperloop, TransPod & AECOM". Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Global Hyperloop Technology Market Analysis, Size, Segmentation and Forecast 2017-2023 by Key Players". Reuters. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Crunchbase - Arrivo". Crunchbase. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Hyperloop startup Arrivo is shutting down as workers are laid off". December 15, 2018.

- "About Hardt". Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Sterling, Toby (June 1, 2017). "Dutch group sets up hyperloop test center". Reuters. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Corder, Mike (June 1, 2017). "Dutch Testing Tube Unveiled for Hyperloop Transport System". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- "Rapport 'Hyperloop in The Netherlands'". Rijksoverheid. October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Bonner, Walt (July 10, 2017). "BLAZING: 'Hyper Chariot' pods can travel 4,000 miles per hour". US: Fox News. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Hyper Chariot". Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Facebook.

- "Zeleros: Overview". LinkedIn. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- "Zeleros | Because time matters". Zeleros. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "MIT leads in first round of Elon Musk's Hyperloop contest, but UW is in the race". GeekWire. February 1, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Service, Purdue News. "Purdue takes collaborative Hyperloop pod to SpaceX competition - Purdue University". www.purdue.edu. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Marca España | First Hyperloop test track in Valencia". marcaespana.es. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "The everis foundation awards a Spanish startup's 'Hyperloop' technology project with €60,000". everis USA. November 22, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "CargoX and Zeleros Hyperloop win the IRU World Congress Startup Competition". www.iru.org. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- "Spain's Zeleros raises 7M€ in financing to lead the development of hyperloop in Europe". June 1, 2020.

- "Hyper Poland jednym z 50 najlepszych startupów w Europie". MamStartup (in Polish). March 5, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- Hawkins, Andrew J. (January 30, 2016). "MIT wins SpaceX's Hyperloop competition, and Elon Musk made a cameo". The Verge. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- Boyle, Alan (June 15, 2015). "Elon Musk's SpaceX Plans Hyperloop Pod Races at California HQ in 2016". NBC. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- "Spacex Hyperloop Pod Competition" (PDF). SpaceX. June 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- "Hyperloop". SpaceX. Space Exploration Technologies. June 9, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- Thompson, Cadie (June 23, 2015). "More than 700 people have signed up to help Elon Musk build a Hyperloop prototype". Business Insider. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- "Hyperloop Competition Rules, v2.0" (PDF). SpaceX. October 20, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- Boyle, Alan (December 15, 2015). "More than 120 teams picked for SpaceX founder Elon Musk's Hyperloop contest". Geekwire.com. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "SpaceX Design Weekend at Texas A&M University". Dwight Look College of Engineering, Texax A&M. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- Kleinman, Jacob (February 1, 2016). "Hyperloop competition winners announced, see the top design". TechnoBuffalo. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- "Hyperloop: MIT students win contest to design Elon Musk's 700mph travel pods". The Guardian. Associated Press. January 30, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- "Awards". Texas A & M University College of Engineering. 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "TU Delft students win Hyperloop Pod Competition". The Netherlands: Delft University of Technology. January 30, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- Murphy, Meg (February 14, 2017). "Safe at any speed". MIT News. Cambridge, MA, USA. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Blodget, Henry (August 20, 2013). "Transport Blogger Ridicules The Hyperloop – Says It Will Cost A Fortune And Be A Terrifying 'Barf Ride'". Business Insider.

- Brandom, Russell (August 16, 2013). "Speed bumps and vomit are the Hyperloop's biggest challenges". The Verge.

- McCurry, Justin (April 21, 2015). "Japan's maglev train breaks world speed record with 600km/h test run". the Guardian.

- Wolverton, Troy (August 13, 2013). "Wolverton: Elon Musk's Hyperloop hype ignores practical problems". The Mercury News. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Salam, Reihan (August 9, 2011). "Alon Levy on Politicals vs. Technicals". National Review. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- Plumer, Brad (August 13, 2013). "There is no redeeming feature of the Hyperloop". The Washington Post.

- "The Future of Transport: No loopy idea". The Economist. Print edition. August 17, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- Anderson, Chris C. (July 15, 2013). "If Elon Musk's Hyperloop Sounds Like Something Out Of Science Fiction, That's Because It Is". Business Insider. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- Beach, Alfred Ely (March 5, 1870). "The Pneumatic Tunnel Under Broadway, N.Y.". Scientific American. 22 (10): 154–156. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican03051870-154.

- "History". Swissmetro.ch. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- Murph, Darren (August 4, 2010). "China's maglev trains to hit 1,000km/h in three years". Engadget.

- Frey, Thomas (October 30, 2013). "Competing for the World's Largest Infrastructure Project: Over 100 Million Jobs at Stake". Futurist Speaker. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- Svaldi, Aldo (August 9, 2013). "Longmont entrepreneur has tubular vision on future of transportation". The Denver Post.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyperloop. |

- Tesla Motors: "Hyperloop Alpha" (PDF).

- SpaceX: "Hyperloop Alpha" (PDF). August 12, 2013

- "Europe's first Hyperloop test track pops up at TU Delft". newatlas.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- The Race to Create Elon Musk's Hyperloop Heats Up, Wall Street Journal, November 30, 2015

- Video of First Successful Test Ride (Wired (magazine)) (YouTube)

- Path Planning for Autonomous Vehicles with Hyperloop Option intellias.com. March 1, 2018.