Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay (Inuktitut: Kangiqsualuk ilua,[2] French: baie d'Hudson) (sometimes called Hudson's Bay, usually historically) is a large body of saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of 1,230,000 km2 (470,000 sq mi). Although not geographically apparent, it is for climatic reasons considered to be a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It drains a very large area, about 3,861,400 km2 (1,490,900 sq mi),[3] that includes parts of southeastern Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec, all of Manitoba and indirectly through smaller passages of water parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana. Hudson Bay's southern arm is called James Bay.

| Hudson Bay | |

|---|---|

Hudson Bay, Canada | |

| |

| Location | North America |

| Coordinates | 60°N 85°W |

| Ocean/sea sources | Arctic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean |

| Catchment area | 3,861,400 km2 (1,490,900 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Canada, United States |

| Max. length | 1,370 km (851.28 mi) |

| Max. width | 1,050 km (652.44 mi) |

| Surface area | 1,230,000 km2 (470,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 100 m (330 ft) |

| Max. depth | 270 m (890 ft)[1] |

| Frozen | mid-December to mid-June |

| Islands | Islands of Hudson Bay |

| Settlements | Rankin Inlet, Arviat, Puvirnituq |

The Eastern Cree name for Hudson and James Bay is Wînipekw (Southern dialect) or Wînipâkw (Northern dialect), meaning muddy or brackish water. Lake Winnipeg is similarly named by the local Cree, as is the location for the city of Winnipeg.

Description

The bay is named after Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Dutch East India Company, and after whom the river that he explored in 1609 is also named. Hudson Bay encompasses 1,230,000 km2 (470,000 sq mi), making it the second-largest water body using the term "bay" in the world (after the Bay of Bengal). The bay is relatively shallow and is considered an epicontinental sea, with an average depth of about 100 m (330 ft) (compared to 2,600 m (8,500 ft) in the Bay of Bengal). It is about 1,370 km (850 mi) long and 1,050 km (650 mi) wide.[4] On the east it is connected with the Atlantic Ocean by Hudson Strait; on the north, with the Arctic Ocean by Foxe Basin (which is not considered part of the bay), and Fury and Hecla Strait.

Hudson Bay is often considered part of the Arctic Ocean; the International Hydrographic Organization, in its 2002 working draft[5] of Limits of Oceans and Seas) defined the Hudson Bay, with its outlet extending from 62.5 to 66.5 degrees north (just a few miles south of the Arctic Circle) as being part of the Arctic Ocean, specifically "Arctic Ocean Subdivision 9.11." Other authorities include it in the Atlantic, in part because of its greater water budget connection with that ocean.[6][7][8][9][10]

Some sources describe Hudson Bay as a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean,[11] or the Arctic Ocean.[12]

Canada treats the bay as an internal body of water and has claimed it as such on historic grounds. This claim is disputed by the United States but no action to resolve it has been taken.[13]

History

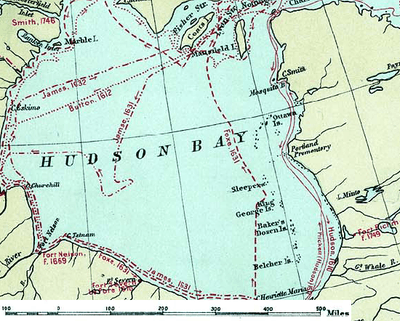

The search for a western route to Cathay and the Indies, which had been actively pursued since the days of Columbus and the Cabots, in the latter part of the fifteenth century, directly resulted in the discovery of Hudson Bay.[14] English explorers and colonists named Hudson Bay after Sir Henry Hudson who explored the bay beginning August 2, 1610 on his ship Discovery.[15]:170 In 1611, Henry Hudson sacrificed his life on its waters, to impress his name indelibly on that great inland sea.[16] On his fourth voyage to North America, Hudson worked his way around Greenland's west coast and into the bay, mapping much of its eastern coast. Discovery became trapped in the ice over the winter, and the crew survived onshore at the southern tip of James Bay. When the ice cleared in the spring, Hudson wanted to explore the rest of the area, but the crew mutinied on June 22, 1611. They left Hudson and others adrift in a small boat. No one knows the fate of Hudson or the crew members stranded with him, but historians see no evidence that they survived for long afterward.[15]:185 In May 1612, Sir Thomas Button sailed from England with two ships to look for Henry Hudson, and to continue the search for the north-west passage to India.[17]

In 1668, Nonsuch reached the bay and traded for beaver pelts, leading to the creation of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) which still bears the historic name.[18] The HBC negotiated a trading monopoly from the English crown for the Hudson Bay watershed, called Rupert's Land.[19]:4 France contested this grant by sending several military expeditions to the region, but abandoned its claim in the Treaty of Utrecht (April 1713).[20]

During this period, the Hudson's Bay Company built several factories (forts and trading posts) along the coast at the mouth of the major rivers (such as Fort Severn, Ontario; York Factory, Churchill, Manitoba and the Prince of Wales Fort). The strategic locations were bases for inland exploration. More importantly, they were trading posts with the indigenous peoples who came to them with furs from their trapping season. The HBC shipped the furs to Europe and continued to use some of these posts well into the 20th century. The Port of Churchill was an important shipping link for trade with Europe and Russia until its closure in 2016 by owner OmniTRAX.[21]

HBC's trade monopoly was abolished in 1870, and it ceded Rupert's Land to Canada, an area of approximately 3,900,000 km2 (1,500,000 sq mi), as part of the Northwest Territories.[19]:427 Starting in 1913, the Bay was extensively charted by the Canadian Government's CSS Acadia to develop it for navigation.[22] This mapping progress led to the establishment of Churchill, Manitoba as a deep-sea port for wheat exports in 1929, after unsuccessful attempts at Port Nelson.

Geography

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the northern limit of Hudson Bay as follows:[23]

A line from Nuvuk Point (62°21′N 78°06′W) to Leyson Point, the Southeastern extreme of Southampton Island, through the Southern and Western shores of Southampton Island to its Northern extremity, thence a line to Beach Point (66°03′N 86°06′W) on the Mainland.

Climate

Northern Hudson Bay has a polar climate (Köppen: ET) being one of the few places in the world where this type of climate is found south of 60 °N, going further south towards Quebec, where Inukjuak is still dominated by the tundra. From Arviat, Nunavut to the west to the south and southeast prevails the subarctic climate (Köppen: Dfc). This is because in the central summer months, heat waves can advance from the hot land and make the weather milder, with the result that the average temperature surpasses 10 °C or 50 °F. At the extreme southern tip of the extension known as James Bay arises a humid continental climate with a longer and generally hotter summer. (Köppen: Dfb)[24] The average annual temperature in almost the entire bay is around 0 °C (32 °F) or below. In the extreme northeast, winter temperatures average as low as −29 °C or −20.2 °F.[25]

The Hudson Bay region has very low year-round average temperatures. The average annual temperature for Churchill at 59°N is −6 °C or 21.2 °F and Inukjuak facing cool westerlies in summer at 58°N an even colder −7 °C or 19.4 °F. By comparison, Magadan in a comparable position at 59°N on the Eurasian landmass in the Russian Far East and with a similar subarctic climate has an annual average of −2.7 °C or 27.1 °F.[26] Vis-à-vis geographically closer Europe, contrasts stand much more extreme. Arkhangelsk at 64°N in northwestern Russia has an average of 2 °C or 36 °F,[27] while the mild continental coastline of Stockholm at 59°N on the shore of an analogous large hyposaline marine inlet – the Baltic Sea – has an annual average of 8 °C or 46 °F.[28]

Water temperature peaks at 8–9 °C (46.4–48.2 °F) on the western side of the bay in late summer. It is largely frozen over from mid-December to mid-June when it usually clears from its eastern end westwards and southwards. A steady increase in regional temperatures over the last 100 years has been reflected in a lengthening of the ice-free period which was as short as four months in the late 17th century.[29]

| Climate data for Arviat Airport (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−20.3 (−4.5) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −29.3 (−20.7) |

−28.3 (−18.9) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −33.1 (−27.6) |

−32.4 (−26.3) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

1.0 (33.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−20.1 (−4.2) |

−27.9 (−18.2) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −48.3 (−54.9) |

−47.0 (−52.6) |

−41.5 (−42.7) |

−36.7 (−34.1) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−34.0 (−29.2) |

−42.5 (−44.5) |

−48.3 (−54.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 10.1 (0.40) |

6.6 (0.26) |

11.4 (0.45) |

12.5 (0.49) |

18.2 (0.72) |

29.6 (1.17) |

36.7 (1.44) |

56.0 (2.20) |

44.0 (1.73) |

24.5 (0.96) |

18.6 (0.73) |

18.3 (0.72) |

286.5 (11.28) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (0.02) |

6.1 (0.24) |

26.3 (1.04) |

36.7 (1.44) |

56.0 (2.20) |

41.2 (1.62) |

7.6 (0.30) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

174.4 (6.87) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 10.1 (4.0) |

6.6 (2.6) |

11.4 (4.5) |

12.1 (4.8) |

12.1 (4.8) |

3.2 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.8 (1.1) |

16.9 (6.7) |

18.8 (7.4) |

18.3 (7.2) |

112.4 (44.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 14.1 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 111.3 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 14.1 | 11.6 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 8.2 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 65.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.1 | 69.9 | 74.4 | 79.8 | 84.6 | 76.8 | 72.7 | 74.7 | 74.6 | 84.1 | 80.7 | 73.3 | 76.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada[30][31] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Churchill Airport (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.9 (98.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −21.9 (−7.4) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −26.0 (−14.8) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −30.1 (−22.2) |

−28.8 (−19.8) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−25.9 (−14.6) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −45.6 (−50.1) |

−45.4 (−49.7) |

−43.9 (−47.0) |

−33.3 (−27.9) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−36.1 (−33.0) |

−43.9 (−47.0) |

−45.6 (−50.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.7 (0.74) |

16.6 (0.65) |

18.1 (0.71) |

23.6 (0.93) |

30.0 (1.18) |

44.2 (1.74) |

59.8 (2.35) |

69.4 (2.73) |

69.9 (2.75) |

48.4 (1.91) |

35.5 (1.40) |

18.4 (0.72) |

452.5 (17.81) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.02) |

1.1 (0.04) |

16.1 (0.63) |

41.0 (1.61) |

59.8 (2.35) |

69.3 (2.73) |

66.0 (2.60) |

20.9 (0.82) |

1.3 (0.05) |

0.1 (0.00) |

276.0 (10.87) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 21.7 (8.5) |

19.3 (7.6) |

20.4 (8.0) |

24.9 (9.8) |

15.5 (6.1) |

3.3 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

4.2 (1.7) |

29.8 (11.7) |

39.2 (15.4) |

22.9 (9.0) |

201.2 (79.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 11.9 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 12.0 | 13.9 | 15.4 | 15.9 | 15.7 | 15.5 | 11.9 | 152.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 10.7 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 6.5 | 0.91 | 0.24 | 67.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 11.9 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.06 | 2.6 | 11.6 | 15.6 | 12.3 | 92.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 79.7 | 117.7 | 177.8 | 198.2 | 197.0 | 243.0 | 281.7 | 225.9 | 112.0 | 58.1 | 55.3 | 53.1 | 1,799.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 36.2 | 45.1 | 48.7 | 45.8 | 37.7 | 44.3 | 51.6 | 47.2 | 29.0 | 18.2 | 23.5 | 26.7 | 37.8 |

| Source: Environment Canada[32][33][34] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Coral Harbour Airport (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | −0.6 | −1.9 | −0.5 | 4.4 | 8.9 | 22.8 | 32.8 | 30.1 | 19.9 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 32.8 |

| Record high °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −25.5 (−13.9) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−20.1 (−4.2) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −29.6 (−21.3) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −33.7 (−28.7) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−20.3 (−4.5) |

−28.6 (−19.5) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −52.8 (−63.0) |

−51.4 (−60.5) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−39.4 (−38.9) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

−48.9 (−56.0) |

−52.8 (−63.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −69.5 | −69.3 | −64.3 | −55.1 | −39.7 | −23.2 | −8.2 | −11.8 | −23.7 | −43.7 | −54.8 | −64.2 | −69.5 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.5 (0.37) |

7.0 (0.28) |

11.2 (0.44) |

18.2 (0.72) |

19.0 (0.75) |

27.6 (1.09) |

34.1 (1.34) |

59.4 (2.34) |

45.4 (1.79) |

33.8 (1.33) |

22.9 (0.90) |

14.8 (0.58) |

302.9 (11.93) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.02) |

4.3 (0.17) |

20.8 (0.82) |

34.1 (1.34) |

58.9 (2.32) |

36.7 (1.44) |

7.2 (0.28) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

163.0 (6.42) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.6 (3.8) |

7.1 (2.8) |

11.3 (4.4) |

18.2 (7.2) |

14.9 (5.9) |

6.9 (2.7) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (0.2) |

8.6 (3.4) |

26.7 (10.5) |

22.9 (9.0) |

14.8 (5.8) |

141.6 (55.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.5 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 125.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 12.5 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 43.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.6 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 87.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.9 | 64.2 | 67.5 | 73.8 | 80.3 | 73.9 | 63.1 | 68.9 | 75.6 | 84.8 | 77.6 | 69.7 | 72.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.9 | 112.1 | 187.4 | 240.2 | 239.9 | 262.2 | 312.3 | 220.4 | 109.8 | 70.8 | 47.9 | 18.8 | 1,859.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.4 | 47.0 | 51.6 | 53.2 | 42.0 | 41.9 | 51.2 | 43.3 | 27.9 | 23.3 | 24.3 | 13.9 | 36.8 |

| Source: Environment Canada Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010[35] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Inukjuak (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | −0.6 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 16.0 | 32.4 | 34.0 | 28.4 | 19.8 | 12.2 | 7.2 | 1.4 | 34.0 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −21.0 (−5.8) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −24.8 (−12.6) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −28.6 (−19.5) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −46.1 (−51.0) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−45.0 (−49.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−43.3 (−45.9) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

| Record low wind chill | −60 | −58 | −55 | −46 | −36 | −15 | −7 | −5 | −12 | −31 | −47 | −55 | −60 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14.4 (0.57) |

11.6 (0.46) |

15.5 (0.61) |

22.6 (0.89) |

27.0 (1.06) |

38.2 (1.50) |

60.1 (2.37) |

61.1 (2.41) |

70.1 (2.76) |

58.6 (2.31) |

50.6 (1.99) |

30.3 (1.19) |

459.9 (18.11) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

3.6 (0.14) |

12.6 (0.50) |

33.6 (1.32) |

59.5 (2.34) |

61.1 (2.41) |

62.2 (2.45) |

28.2 (1.11) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0.4 (0.02) |

264.6 (10.42) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.0 (5.9) |

12.0 (4.7) |

16.1 (6.3) |

19.4 (7.6) |

14.6 (5.7) |

4.4 (1.7) |

1.0 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

7.5 (3.0) |

32.6 (12.8) |

50.0 (19.7) |

32.0 (12.6) |

204.5 (80.5) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 8.5 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 16.2 | 8.6 | 1.2 | 0.13 | 68.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 10.8 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 8.4 | 3.6 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 5.0 | 15.6 | 20.3 | 15.3 | 107.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.5 | 122.5 | 182.5 | 183.2 | 159.4 | 209.4 | 226.0 | 171.7 | 97.9 | 50.4 | 31.8 | 35.2 | 1,533.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 28.6 | 46.7 | 49.9 | 42.5 | 30.6 | 38.4 | 41.6 | 36.0 | 25.4 | 15.8 | 13.4 | 17.5 | 32.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada[36] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Kuujjuarapik Airport (1981−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −18.7 (−1.7) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

0.4 (32.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −23.3 (−9.9) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−15 (5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −27.8 (−18.0) |

−28.3 (−18.9) |

−22.6 (−8.7) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −49.4 (−56.9) |

−48.9 (−56.0) |

−45.0 (−49.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−46.1 (−51.0) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 27.9 (1.10) |

22.7 (0.89) |

23.2 (0.91) |

23.7 (0.93) |

33.5 (1.32) |

59.6 (2.35) |

75.8 (2.98) |

91.6 (3.61) |

109.3 (4.30) |

81.6 (3.21) |

65.9 (2.59) |

46.1 (1.81) |

660.8 (26.02) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.05 (0.00) |

0.64 (0.03) |

2.1 (0.08) |

6.9 (0.27) |

19.9 (0.78) |

55.1 (2.17) |

75.9 (2.99) |

91.6 (3.61) |

106.5 (4.19) |

53.4 (2.10) |

9.4 (0.37) |

0.65 (0.03) |

422.0 (16.61) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 29.3 (11.5) |

22.8 (9.0) |

22.1 (8.7) |

17.3 (6.8) |

14.3 (5.6) |

4.4 (1.7) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.9 (1.1) |

29.4 (11.6) |

58.5 (23.0) |

47.9 (18.9) |

248.8 (98.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.2 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 20.8 | 21.6 | 22.0 | 21.3 | 195.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.17 | 0.38 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 6.9 | 10.6 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 14.1 | 3.6 | 0.41 | 90.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 17.2 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 12.1 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 118.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 71.7 | 112.7 | 155.8 | 165.2 | 166.4 | 205.0 | 213.5 | 163.7 | 81.8 | 64.4 | 34.2 | 40.0 | 1,474.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 29.6 | 41.5 | 42.5 | 39.0 | 33.2 | 39.4 | 41.0 | 35.2 | 21.3 | 19.8 | 13.5 | 17.8 | 31.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada[37] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Rankin Inlet Airport (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | −3.0 | −4.4 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 13.4 | 26.3 | 32.2 | 31.8 | 21.8 | 11.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 32.2 |

| Record high °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.4 (38.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

0.9 (33.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −27.3 (−17.1) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−21.9 (−7.4) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −30.8 (−23.4) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −34.4 (−29.9) |

−33.6 (−28.5) |

−29.2 (−20.6) |

−20.1 (−4.2) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

0.5 (32.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −46.1 (−51.0) |

−49.8 (−57.6) |

−43.4 (−46.1) |

−35.7 (−32.3) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−36.5 (−33.7) |

−43.6 (−46.5) |

−49.8 (−57.6) |

| Record low wind chill | −66.8 | −70.5 | −64.4 | −53.6 | −35.9 | −17.6 | −5.3 | −8.8 | −18.1 | −42.7 | −55.3 | −62.4 | −70.5 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8.7 (0.34) |

8.2 (0.32) |

12.3 (0.48) |

19.9 (0.78) |

19.5 (0.77) |

26.6 (1.05) |

42.0 (1.65) |

57.4 (2.26) |

42.9 (1.69) |

38.0 (1.50) |

21.7 (0.85) |

12.8 (0.50) |

310.1 (12.21) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.1 (0.04) |

7.0 (0.28) |

22.1 (0.87) |

41.9 (1.65) |

57.2 (2.25) |

39.1 (1.54) |

12.9 (0.51) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

181.8 (7.16) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 8.9 (3.5) |

8.5 (3.3) |

12.5 (4.9) |

19.2 (7.6) |

13.0 (5.1) |

4.6 (1.8) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.1) |

3.8 (1.5) |

25.5 (10.0) |

22.4 (8.8) |

13.3 (5.2) |

131.9 (51.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.8 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 14.9 | 12.6 | 10.0 | 122.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 10.4 | 13.2 | 10.5 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 48.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.8 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 10.0 | 79.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.2 | 67.3 | 71.3 | 79.0 | 82.3 | 72.3 | 66.6 | 70.6 | 76.3 | 84.5 | 78.4 | 70.2 | 73.7 |

| Source: Environment Canada Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010[38] | |||||||||||||

Waters

Hudson Bay has a lower average salinity level than that of ocean water. The main causes are the low rate of evaporation (the bay is ice-covered for much of the year), the large volume of terrestrial runoff entering the bay (about 700 km3 (170 cu mi) annually, the Hudson Bay watershed covering much of Canada, many rivers and streams discharging into the bay), and the limited connection with the Atlantic Ocean and its higher salinity. Sea ice is about three times the annual river flow into the bay, and its annual freezing and thawing significantly alters the salinity of the surface layer.

One consequence of the lower salinity of the bay is that the freezing point of the water is higher than in the rest of the world's oceans, thus decreasing the time that the bay remains ice-free.

Shores

The western shores of the bay are a lowland known as the Hudson Bay Lowlands which covers 324,000 km2 (125,000 sq mi). The area is drained by a large number of rivers and has formed a characteristic vegetation known as muskeg. Much of the landform has been shaped by the actions of glaciers and the shrinkage of the bay over long periods of time. Signs of numerous former beachfronts can be seen far inland from the current shore. A large portion of the lowlands in the province of Ontario is part of the Polar Bear Provincial Park, and a similar portion of the lowlands in Manitoba is contained in Wapusk National Park, the latter location being a significant polar bear maternity denning area.[39]

In contrast, most of the eastern shores (the Quebec portion) form the western edge of the Canadian Shield in Quebec. The area is rocky and hilly. Its vegetation is typically boreal forest, and to the north, tundra.

Measured by shoreline, Hudson Bay is the largest bay in the world (the largest in area being the Bay of Bengal).

Islands

There are many islands in Hudson Bay, mostly near the eastern coast. All, as are the islands in James Bay, are part of Nunavut and lie in the Arctic Archipelago. Several are disputed by the Cree.[40] One group of islands is the Belcher Islands. Another group includes the Ottawa Islands.

Geology

Hudson Bay occupies a large structural basin, known as the Hudson Bay basin, that lies within the Canadian Shield. The collection and interpretation of outcrop, seismic and drillhole data for exploration for oil and gas reservoirs within the Hudson Bay basin found that it is filled by, at most, 2,500 m (8,200 ft) of Ordovician to Devonian limestone, dolomites, evaporites, black shales, and various clastic sedimentary rocks that overlie less than 60 m (200 ft) of Cambrian strata that consist of unfossiliferous quartz sandstones and conglomerates, overlain by sandy and stromatolitic dolomites. In addition, a minor amount of terrestrial Cretaceous fluvial sands and gravels are preserved in the fills of a ring of sinkholes created by the dissolution of Silurian evaporites during the Cretaceous Period.[41][42][43][44]

From the large quantity of published geologic data that has been collected as the result of hydrocarbon exploration, academic research, and related geologic mapping, a detailed history of the Hudson Bay basin has been reconstructed.[42] During the majority of the Cambrian Period, this basin did not exist. Rather, this part of the Canadian Shield area was still topographically high and emergent. It was only during the later part of the Cambrian that the rising sea level of the Sauk marine transgression slowly submerged it. During the Ordovician, this part of the Canadian Shield continued to be submerged by rising sea levels except for a brief middle Ordovician marine regression. Only starting in the Late Ordovician and continuing into the Silurian did the gradual regional subsidence of this part of the Canadian Shield form the Hudson Bay basin. The formation of this basin resulted in the accumulation of black bituminous oil shale and evaporite deposits within its centre, thick basin-margin limestone and dolomite, and the development of extensive reefs that ringed the basin margins that were tectonically uplifted as the basin subsided. During Middle Silurian times, subsidence ceased and this basin was uplifted. It generated an emergent arch, on which reefs grew, that divided the basin into eastern and western sub-basins. During the Devonian Period, this basin filled with terrestrial red beds that interfinger with marine limestone and dolomites. Before deposition was terminated by marine regression, Upper Devonian black bituminous shale accumulated in the south-east of the basin.[41][42][43][44]

The remaining history of the Hudson Bay basin is largely unknown as a major unconformity separates Upper Devonian strata from glacial deposits of the Pleistocene. Except for poorly known terrestrial Cretaceous fluvial sands and gravels that are preserved as the fills of a ring of sinkholes around the centre of this basin, strata representing this period of time are absent from the Hudson Bay basin and the surrounding Canadian Shield.[41][44]

The Precambrian Shield underlying Hudson Bay and in which Hudson Bay basin formed is composed of two Archean proto-continents, the Western Churchill and Superior cratons. These cratons are separated by a tectonic collage that forms a suture zone between these cratons and the Trans-Hudson Orogen. The Western Churchill and Superior cratons collided at about 1.9–1.8 Ga in the Trans-Hudson orogeny. Because of the irregular shapes of the colliding cratons, this collision trapped between them large fragments of juvenile crust, a sizable microcontinent, and island arc terranes, beneath what is now the centre of modern Hudson Bay as part of the Trans-Hudson Orogen. The Belcher Islands are the eroded surface of the Belcher Fold Belt, which formed as a result of the tectonic compression and folding of sediments that accumulated along the margin of the Superior Craton before its collision with the Western Churchill Craton.[45][46]

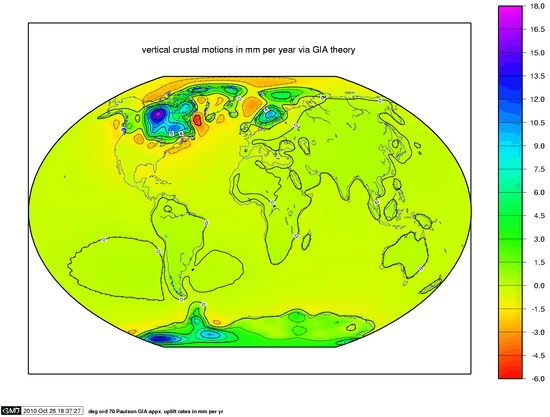

Hudson Bay and the associated structural basin lies within the centre of a large free-air gravity anomaly that lies within the Canadian Shield. The similarity in areal extent of the free-air gravity anomaly with the perimeter of the former Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered this part of Laurentia led to a long-held conclusion that this perturbation in the Earth’s gravity reflected still ongoing glacial isostatic adjustment to the melting and disappearance of this ice sheet. Data collected over Canada by the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite mission allowed geophysicists to isolate the gravity signal associated with glacial isostatic adjustment from longer–time scale process of mantle convection occurring beneath the Canadian Shield. Based upon this data, geophysicists and other Earth scientists concluded that the Laurentide Ice Sheet was composed of two large domes to the west and east of Hudson Bay. Modeling glacial isostatic adjustment using the GRACE data, they concluded that ~25 to ~45% of the observed free-air gravity anomaly was due to ongoing glacial isostatic adjustment, and the remainder likely represents longer time-scale effects of mantle convection.[47]

Southeastern semicircle

Earth scientists have disagreed about what created the semicircular feature known as the Nastapoka arc that forms a section of the shoreline of southeastern Hudson Bay. Noting the paucity of impact structures on Earth in relation to the Moon and Mars, Carlyle Smith Beals[48] proposed that it is possibly part of a Precambrian extraterrestrial impact structure that is comparable in size to the Mare Crisium on the Moon. In the same volume, John Tuzo Wilson[49] commented on Beals' interpretation and alternately proposed that the Nastapoka arc may have formed as part of an extensive Precambrian continental collisional orogen, linked to the closure of an ancient ocean basin. The current general consensus is that it is an arcuate boundary of tectonic origin between the Belcher Fold Belt and undeformed basement of the Superior Craton created during the Trans-Hudson orogeny. This is because no credible evidence for such an impact structure has been found by regional magnetic, Bouguer gravity, or other geologic studies.[45][46] However, other Earth scientists have proposed that the evidence of an Archean impact might have been masked by deformation accompanying the later formation of the Trans-Hudson orogen and regard an impact origin as a plausible possibility.[50][51]

Economy

.svg.png)

Arctic Bridge

The longer periods of ice-free navigation and the reduction of Arctic Ocean ice coverage have led to Russian and Canadian interest in the potential for commercial trade routes across the Arctic and into Hudson Bay. The so-called Arctic Bridge would link Churchill, Manitoba, and the Russian port of Murmansk.[52]

Port

The biggest port in the Hudson bay is the city of Churchill, which lays on the river with the same name, Churchill River. The Port of Churchill is a privately-owned port on Hudson Bay in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Routes from the port connect to the North Atlantic through the Hudson Strait. As of 2008, the port had four deep-sea berths capable of handling Panamax-size vessels for the loading and unloading of grain, bulk commodities, general cargo, and tanker vessels. The port is connected to the Hudson Bay Railway, which shares the same parent company, and cargo connections are made with the Canadian National Railway system at HBR's southern terminus in The Pas. It is the only port of its size and scope in Canada that does not connect directly to the country's road system; all goods shipped overland to and from the port must travel by rail.

The port was originally owned by the Government of Canada but was sold in 1997 to the American company OmniTRAX to run privately. In December 2015, OmniTRAX announced it was negotiating a sale of the port, and the associated Hudson Bay Railway, to a group of First Nations based in northern Manitoba.[53] [54]With no sale finalized by July 2016, OmniTRAX shut down the port and the major railroad freight operations in August 2016.[55] The railway continued to carry cargo to supply the town of Churchill itself until the line was damaged by flooding on May 23, 2017. The Port and the Hudson Bay Railway were sold to Arctic Gateway Group — a consortium of First Nations, local governments, and corporate investors — in 2018.[56] On July 9, 2019, ships on missions to resupply arctic communities began stopping at the port for additional cargo,[57] and the port began shipping grain again on September 7, 2019.[58]

Coastal communities

The coast of Hudson Bay is extremely sparsely populated; there are only about a dozen communities. Some of these were founded as trading posts in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Hudson's Bay Company, making them some of the oldest settlements in Western Canada. With the closure of the HBC posts and stores, although many are now run by The North West Company,[59] in the second half of the 20th century, many coastal villages are now almost exclusively populated by Cree and Inuit people. Two main historic sites along the coast were York Factory and Prince of Wales Fort.

Communities along the Hudson Bay coast or on islands in the bay are (all populations are as of 2016):

- Nunavut

- Arviat, population 2,657[60]

- Chesterfield Inlet, population 437[61]

- Coral Harbour, population 891[62]

- Rankin Inlet, population 2,842[63]

- Sanikiluaq, population 882[64]

- Whale Cove, population 435[65]

- Manitoba

- Ontario

- Fort Severn First Nation, population 361[67]

- Quebec

- Akulivik, population 633[68]

- Inukjuak, population 1,757[69]

- Kuujjuarapik, population 686[70]

- Puvirnituq, population 1,779[71]

- Umiujaq, population 442[72]

- Whapmagoostui, population 984[73]

Military development

The Hudson's Bay Company built forts as fur trade strongholds against the French or other possible invaders. One example is York Factory with angled walls to help defend the fort. In the 1950s, during the Cold War, a few sites along the coast became part of the Mid-Canada Line, watching for a potential Soviet bomber attack over the North Pole. The only Arctic deep-water port in Canada is the Port of Churchill, located at Churchill, Manitoba.

See also

- Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

- Lake Agassiz – A very large glacial lake in central North America at the end of the last glacial period

- List of Hudson Bay rivers

- Tyrrell Sea – Prehistoric sea covering Hudson Bay

References

- "Hudson Bay | sea, Canada". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Wissenladen – Willkommen". www.posterwissen.de.

- "Canada Drainage Basins". The National Atlas of Canada, 5th edition. Natural Resources Canada. 1985. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Private Tutor. Infoplease.com. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- "IHO Publication S-23 Limits of Oceans and Seas; Chapter 9: Arctic Ocean". International Hydrographic Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- Lewis, Edward Lyn; Jones, E. Peter; et al., eds. (2000). The Freshwater Budget of the Arctic Ocean. Springer. pp. 101, 282–283. ISBN 978-0-7923-6439-9. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- McColl, R.W. (2005). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Earle, Sylvia A.; Glover, Linda K. (2008). Ocean: An Illustrated Atlas. National Geographic Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4262-0319-0. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Reddy, M. P. M. (2001). Descriptive Physical Oceanography. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-5410-706-4. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Day, Trevor; Garratt, Richard (2006). Oceans. Infobase Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8160-5327-8. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Calow, Peter (12 July 1999). Blackwell's concise encyclopedia of environmental management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-632-04951-6. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- Wright, John (30 November 2001). The New York Times Almanac 2002. Psychology Press. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-57958-348-4. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- Companies, British and American Joint Commission for the Final Settlement of the Claims of the Hudson's Bay and Puget's Sound Agricultural (1867). Evidence for the United States in the matter of the claims of the Hudson's Bay and Puget's Sound Agricultural Companies. Miscellaneous. Washington, M'Gill & Witherow, Printers, 1867. 2 p. l., 397 p. 25 cm. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Tyrrell, J.B., ed. (1931). Documents Relating to the Early History of Hudson Bay. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 3.

- Butts, Edward (2009-12-31). Henry Hudson: New World voyager. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-55488-455-1. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Tyrrell, J.B., ed. (1931). Documents Relating to the Early History of Hudson Bay. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 3.

- Tyrrell, J.B., ed. (1931). Documents Relating to the Early History of Hudson Bay. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 3.

- "Nonsuch Gallery". Manitoba Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Galbraith, John S. (1957). The Hudson's Bay Company. University of California Press.

- Tyrrell, Joseph (1931). Documents Relating to the Early History of Hudson Bay: The Publications of the Champlain Society. Toronto: Champlain Society. doi:10.3138/9781442618336.

- "Port of Churchill shut down after being refused bailout, premier suggests | The Star". thestar.com.

- "CSS Acadia". Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "Interactive Canada Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map". www.plantmaps.com. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- s.r.o., © Solargis. "Solargis :: iMaps". solargis.info. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "КЛИМАТ МАГАДАНА". Погода и Климат. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- GHCN climatic monthly data, GISS, using 1995–2007 annual averages

- "Climate normals for Sweden 1981-2010". Météo Climat. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- General Survey of World Climatology, Landsberg ed., (1984), Elsevier.

- "Arviat A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2300MKF. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- "Arviat Climate". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Churchill A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- "Churchill Marine". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- "Churchill Climate". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- "Coral Harbour A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2301000. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000". Environment Canada. Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- "Kuujjuarapik Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- "Rankin Inlet A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2303401. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, globalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg Archived 2008-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Cree ask court to defend traditional rights on James Bay islands". Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- Burgess, P.M., 2008, Phanerozoic evolution of the sedimentary cover of the North American craton., in Miall, A.D., ed., Sedimentary Basins of the United States and Canada, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, pp. 31–63.

- Lavoie, D., Pinet, N., Dietrich, J. and Chen, Z., 2015. The Paleozoic Hudson Bay Basin in northern Canada: New insights into hydrocarbon potential of a frontier intracratonic basin. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 99(5), pp. 859–888.

- Roksandic, M.M., 1987, The tectonics and evolution of the Hudson Bay region, in C. Beaumont and A. J. Tankard, eds., Sedimentary basins and basin-forming mechanisms. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists Memoir 12, p. 507–518.

- Sanford, B.V. and Grant, A.C., 1998. Paleozoic and Mesozoic geology of the Hudson and southeast Arctic platforms. Geological Survey of Canada Open File 3595, scale 1:2 500 000.

- Darbyshire, F.A., and Eaton, D.W., 2010. The lithospheric root beneath Hudson Bay, Canada from Rayleigh wave dispersion: No clear seismological distinction between Archean and Proterozoic mantle, Lithos. 120(1-2), 144–159, doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2010.04.010.

- Eaton, D.W., and Darbyshire, F., 2010. Lithospheric architecture and tectonic evolution of the Hudson Bay region, Tectonophysics. 480(1-4), 1–22, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.09.006.

- Tamisiea, M.E., Mitrovica, J.X. and Davis, J.L., 2007. GRACE gravity data constrain ancient ice geometries and continental dynamics over Laurentia. Science, 316(5826), pp. 881–883.

- Beals, C.S., 1968. On the possibility of a catastrophic origin for the great arc of eastern Hudson Bay. In: Beals, C.S. (Ed.), pp. 985–999. Science, History and Hudson Bay, Vol. 2, Department of Energy Mines and Resources, Ottawa.

- Wilson, J.T., 1968. Comparison of the Hudson Bay arc with some other features. In: Beals, C.S. (Ed.), pp. 1015–1033. Science, History and Hudson Bay, Vol. 2. Department of Energy Mines and Resources, Ottawa.

- Goodings, C.R. & Brookfield, M.E., 1992. Proterozoic transcurrent movements along the Kapuskasing lineament (Superior Province, Canada) and their relationship to surrounding structures. Earth-Science Reviews, 32: 147–185.

- Bleeker, W., and Pilkington, M., 2004. The 450-km-diameter Nastapoka Arc: Earth's oldest and largest preserved impact scar? Program with Abstracts – Geological Association of Canada; Mineralogical Association of Canada: Joint Annual Meeting, 2004, Vol. 29, pp. 344.

- "Russian ship crosses 'Arctic bridge' to Manitoba". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009.

- "OmniTrax sells Port of Churchill, Hudson Bay rail line to First Nations group". CBC News. December 19, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- "Port of Churchill shut down after being refused bailout, premier suggests | The Star". thestar.com. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "How Ottawa abandoned Churchill, our only Arctic port". www.macleans.ca. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Kavanagh, Sean (September 14, 2018). "Feds to spend $117M for Churchill railway sale, repairs". CBC News. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- "First ship docks at Churchill July 9 to load cargo bound for Nunavut". Thompson Citizen. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Grain leaves Churchill for first time in four years". Grainews. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Operations | The North West Company". www.northwest.ca.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Arviat". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Statistics Canada: 2016 Census Profile Chesterfield Inlet". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "2016 Coral Harbour Census". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Rankin Inlet". Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Sanikiluaq". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- "Statistics Canada: 2016 Census Profile Whale Cove". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Churchill, Town [Census subdivision], Manitoba and Division No. 23, Census division [Census division], Manitoba". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Fort Severn 89, Indian reserve [Census subdivision], Ontario and Kenora, District [Census division], Ontario". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "(Code 2499125) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017.

- "(Code 2499085) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Kuujjuarapik, Village nordique [Census subdivision], Quebec and Nord-du-Québec, Census division [Census division], Quebec". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Puvirnituq, Village nordique [Census subdivision], Quebec and Quebec [Province]". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Umiujaq, Village nordique [Census subdivision], Quebec and Nord-du-Québec, Census division [Census division], Quebec". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Census Profile". Canada 2016 Census. Statistics Canada.

Notes

- Atlas of Canada, online version.

- Some references of geological/impact structure interest include:

- Rondot, Jehan (1994). Recognition of eroded astroblemes. Earth-Science Reviews 35, 4, p. 331–365.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (1968) Comparison of the Hudson Bay arc with some other features. In: Science, History and Hudson Bay, v. 2. Beals, C. S. (editor), p. 1015–1033.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hudson Bay. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). 1911.