Hub-center steering

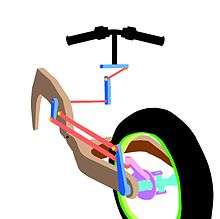

Hub-center steering (HCS) is one of several different types of front end suspension/steering mechanisms used in motorcycles and cargo bicycles. Hub-center steering is characterized by the steering pivot points being inside the hub of the wheel, rather than above the wheel in the headstock as in the traditional layout. Most hub-center arrangements employ a swingarm that extends from the bottom of the engine/frame to the centre of the front wheel.

The advantages of using a hub-center steering system instead of a more conventional motorcycle fork are that hub-center steering separates the steering, braking, and suspension functions.

With a fork the braking forces are put through the suspension, a situation that leads to the suspension being compressed, using up a large amount of suspension travel which makes dealing with bumps and other road irregularities extremely difficult. As the forks dive the steering geometry of the bike also changes making the bike more nervous, and inversely on acceleration becomes more lazy. Also, having the steering working through the forks causes problems with stiction, decreasing the effectiveness of the suspension. The length of the typical motorcycle fork means that they act as large levers about the headstock requiring the forks, the headstock, and the frame to be very robust adding to the bike's weight.

Hub-center steering systems use an arm, or arms, on bearings to allow upward wheel deflection, meaning that there is no stiction, even under braking. Braking forces can be redirected horizontally along these arms, or tie rods, away from the vertical suspension forces, and can even be put to good use to counteract weight shift. Finally, the arms typically form some form of parallelogram which maintains steering geometry over the full range of wheel travel, allowing agility and consistency of steering that forks currently cannot get close to attaining. The hub center steering's Achilles heel, however, has been steering feel. Complex linkages tend to be involved in the steering process, and this can lead to slack, vague, or inconsistent handlebar movement across its range.

Hub-center steering systems have only appeared on a very few production motorcycles, and not with any great success. Evolution, rather than revolution, tends to drive advancements in new models, and dictate sales. After so many years of telescopic forks, people are used to riding a bike that handles in a specific way, and almost expect the limitations, and compensation is part of the experience. Also there is a depth of knowledge known about fork based chassis design that attempts each year to get around the limitations through technological advances on the current system. Thicker and thicker fork tubes are used to reduce flex, special coatings are used to aid stiction, and greater and greater steering angles are used to counteract dive.

The hub-center steer concept is a very old one used as early as 1910 by the British James Cycle Co, and in 1920 by Ner-a-Car, and enjoyed an aftermarket vogue in the 1970s through the work of Jack Difazio in the UK. Mead & Tomkinson Racing pioneered the use of hub-centre steering in long-distance motorcycle endurance racing. Their first version of "Nessie" was powered by a modified Laverda 3C 1000 cc triple, but they later designed a Kawasaki-engined bike that became known as Nessie II. The Tomkinson's efforts encouraged the Elf racing team in the 1980s to create a succession of endurance and GP race bikes. In the 90's there was a flurry of action, first was the Bimota Tesi 1D in 1991 however this was expensive and was only ever produced in small numbers. Then in 1993 Yamaha launched the GTS1000 based on James Parker's RADD design. It raced at the Isle of Man TT but was always blighted with a reputation for being a bit heavy and clumsy in use.

However, Steven Linsdell changed this reputation slightly with an 8th place finish in the 1994 Formula One TT, 6th place in the 1995 Formula one TT and 10th place in 1996 on his Flitwick Motorcycles machine, with very competitive times against factory machines from the likes of Honda and their RC45. His prototype, based on a heavily modified Yamaha GTS1000, featured a Yamaha YZF750 engine due to the Formula one regulations and achieved 178mph through the Sulby speedtrap section of the course. His average speed of over 117mph on the twisty and undulating 37.73 mile long hedge and wall lined street course was very reputable at an international event, on a machine built in his garden workshop during his spare time away from work.

Michael Tryphonos also built a prototype based on the Defazio system that did race at the Isle of Man with some success reaching 11th in the Senior TT.

Royce Creasey, designer of feet forwards motorcycles, is an ardent advocate of HCS.

Currently, Bimota's Tesi 3D and the Vyrus 984C3 2V and the 985C3 4V are the only production motorcycles using hub-center steering systems, however Italjet also use hub-center steering on their top of the range scooters. Sidecar manufacturers occasionally employ hub-center steering in their designs, such as the GG Duetto. An aftermarket hub center steering assembly is made by ISR Brakes of Sweden.[1]

Cargo bicycles

Cargo bicycles have a low-set cargo platform ahead of the rider with a small diameter front wheel ahead of this. The conventional fork and steerer rises above this, often inconveniently for cargo loading. In 2011 Elian developed a cargo bicycle with hub-centre steering to the wheel.[2]

References

- Hub Center Steering Kit from ISR of Sweden

- "A revolutionary ride". Elian Cycles.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hub-center steering. |

- Steering For The Future by Tony Foale - Expert article on alternative motorcycle front suspension systems