Horace Pippin

Horace Pippin (February 22, 1888 – July 6, 1946) was a self-taught American artist who painted a range of themes, including scenes inspired by his service in World War I, landscapes, portraits, and biblical subjects. Some of his best-known works address the U.S.'s history of slavery and racial segregation.

Horace Pippin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 22, 1888 |

| Died | July 6, 1946 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

A Pennsylvania State historical Marker was placed at 327 Gay Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania, to commemorate his accomplishments and mark his home where he lived at the time of his death.[1] He was eulogized by the New York Times upon his death as the "most important Negro painter" in American history.[2] He is buried at Chestnut Grove Annex Cemetery in West Goshen Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania.[3]

Early life

He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1888, on Washington's birthday, to Horace and Harriet Pippin.[4] He grew up in and around Goshen, New York, but would return to West Chester in adulthood.[5] In Goshen, he attended segregated schools until he was 15, when he went to work to support his ailing mother.[6] As a boy, Horace responded to an art supply company's advertising contest and won his first set of crayons and a box of watercolors. As a youngster, Pippin made drawings of racehorses and jockeys from Goshen's celebrated racetrack.[5] Prior to 1917, Pippin worked as a hotel porter, a furniture packer, and an iron moulder.[7] He was a member of St. John's African Union Methodist Protestant Church.[8] In 1920, Pippin married Jennie Fetherstone Wade Giles, who had been widowed twice and had a six-year-old-son.[5]

World War I

In World War I, Pippin served in K Company, the 3rd Battalion of the 369th infantry, known for their bravery in battle as the famous Harlem Hellfighters. The Hellfighters, an all black infantry, were faced with so much prejudice that they were placed under the command of the French Army. They were the longest serving regiment on the war's frontlines, holding their ground against enemy fire almost continuously from mid-July until the end of the war.[9] In October 1918, Pippin was shot in the right shoulder by a German sniper. The injury initially cost him the use of his arm and always limited his range of motion. He was honorably discharged in 1919 and earned the French Croix de Guerre in the same year. He was retroactively awarded a Purple Heart for his service in 1945.[5] He said of his combat experience:

I did not care what or where I went. I asked God to help me, and he did so. And that is the way I came through that terrible and Hellish place. For the whole entire battlefield was hell, so it was no place for any human being to be.[10]

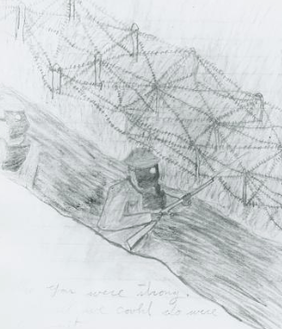

During the war, Pippin created illustrated journals that describe his military service.[11][12] These works document his experience serving in a segregated military as well as the inventions of modern warfare.[9] Pippin's return from war marked the start of a serious art practice in which he began to process the ordeal of war pictorially while incidentally performing a kind of physical therapy. The artist has stated that WWI "brought out all the art in me".[5]

- Horace Pippin's War Diary Notebooks, 1917–18

Three Soldiers on March

Three Soldiers on March Soldiers with Gas Masks in Trench

Soldiers with Gas Masks in Trench

Career

Although Pippin displayed an interest in art throughout childhood, he started his art practice in earnest rather late in life, nearing the age of forty.[13] Pippin took up art in the 1920s, reportedly in part to rehabilitate from the war, and began painting in oil in 1930 with The End of the War: Starting Home. He later explained his creative process: "The pictures which I have already painted come to me in my mind, and if to me it is a worth while picture, I paint it."[14] He addressed a range of themes, from landscapes and still lifes to biblical subjects and political statements. Some draw on his personal experience of the war or turn-of-the-century domestic life.

His "discovery" came when his painting Cabin in the Cotton I caught the eyes of art critic Christian Brinton and artist N.C. Wyeth. Pippin's work was exhibited for the first time by Brinton, who arranged to have his paintings shown at the West Chester Community Center in 1937, marking the onset of Pippin's swift rise to fame.[15] He soon attracted curators Dorothy Miller and Holger Cahill and, by 1940, the Philadelphia art dealer Robert Carlen and the collector Albert C. Barnes. Carlen and Barnes played especially prominent roles in Pippin's career. Pippin attended art appreciation classes at the Barnes Foundation in the spring 1940 semester.[16]

In the eight years between his national debut in the Museum of Modern Art's traveling exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting” (1938) and his death at the age of fifty-eight, Pippin's recognition grew exponentially across the country and internationally. During this period, he had solo exhibitions in commercial galleries in Philadelphia (1940, 1941) and New York (1940, 1944), and at the Arts Club of Chicago (1941), and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1942). Private collections and museums such as the Barnes Foundation, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, acquired his works. His paintings were featured in national surveys held at the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, PA; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Dayton Art Institute, OH; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. and Tate Gallery, London, UK.[16]

In the catalogue for his memorial exhibition in 1947, critic Alain Locke described Pippin as "a real and rare genius, combining folk quality with artistic maturity so uniquely as almost to defy classification."

Artworks

Pippin's oeuvre includes a variety of subject matter and compositional strategies. Beginning with art that reflected his experience in the war, Pippin went on to create landscapes, portraits, history and genre paintings, and biblical scenes.

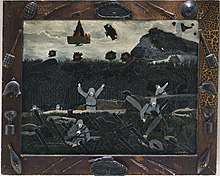

His first oil painting,The End of the War: Starting Home, 1930, depicts the cease-fire going into effect on November 11, 1918.[17] Out of the many war-related pictures Pippin made, this is the only one that portrays a scene at which the artist could not have been present. At the time of the German surrender, Pippin would have been recovering from his gunshot wound in a French hospital.[17] He depicted World War I several times thereafter in the 1930s and once more in 1945. Another unique feature of this work is its custom frame, which Pippin embellished with material signifiers of combat. Various weapons surround a German infantry helmet on the frame's left, which mirrors a French infantry helmet on the right.[18]

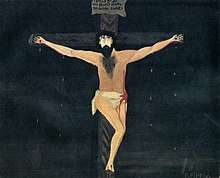

Pippin painted several religious subjects, both those illustrating Bible passages and more visionary statements like his Holy Mountain series. He was a religious man, staying close to the church throughout his life by teaching Sunday school and singing in his church choir.[19]

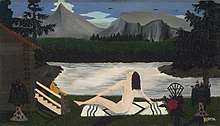

Some of Pippin's most celebrated pictures include his Holy Mountain series. Reminiscent of the bucolic Peaceable Kingdom series by Quaker artist Edward Hicks, Pippin's work adds elements that contextualize the theme in his own time. Barely visible figures in the backgrounded forest reveal forces that may precede or threaten the peace rendered in the foreground. In The Holy Mountain I and III, a brown silhouetted figure can be seen hanging among the trees, presumably a victim of lynching, which was a not uncommon atrocity in the segregated southern United States.[20] Among the paintings, soldiers, airplanes, bombs, and grave markers are also visible in the forest. Pippin suggests that discord and harmony are never too far apart. He links concepts of destruction to those of peace again by signing each painting in the series with a significant date from WWI. The Holy Mountain I is marked with "June 6", dating to D-Day. "Dec 7" marks The Holy Mountain II, signifying the attack on Pearl Harbor. Lastly, The Holy Mountain III is dated "Aug 9", the day the United Stated dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan.[21] In the foreground, it has been noted that the shepherd figure, which Pippin added among the animals also seen in Hicks' works, bears a striking resemblance to the artist himself.[20] Pippin's dealer Robert Carlen likely exposed Pippin to Hicks' series as he was a principle advocate of both self-taught artists.[22]

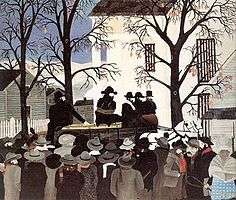

His Self-portrait of 1941 shows him seated at the easel. His painting of John Brown Going to his Hanging (1942) is in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia is part of a trilogy on the subject of the abolitionist who is sometimes credited with igniting the Civil War.

Horace Pippin, John Brown Going to His Hanging

Horace Pippin, John Brown Going to His Hanging

His portraits include a depiction of the contralto Marian Anderson singing, painted in 1941.

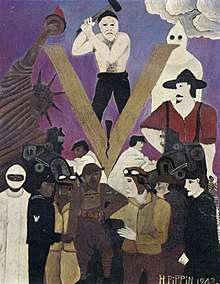

Mr. Prejudice, made at the request of an unidentified patron, is unique in Pippin's oeuvre for its experimental composition and more overt use of iconography. The image sorts figures compositionally by race, with an African-American group on the left and white group on the right. The lower register reveals an assortment of military types. It has been suggested that the figure at center left, a soldier outfitted in an anachronistic WWI uniform, could signify Pippin himself. The black figures face forward, towards the viewer, while the white figures face left, towards the African-American group. In the painting's upper register, a white man is seen with a hammer, presumably splitting the large, golden V that surrounds him and divides the figures below. Winston Churchill coined the slogan "V for Victory" in the Allied campaign to end WWII. The slogan was expanded by African-American groups into the "Double V" campaign, which elaborated on the hope for victory abroad to include victory over discrimination and racism at home. Larger figures are shown along the edges of the picture's upper register. On the left, a brown-skinned Statue of Liberty raises her torch, lighting the way to freedom. On the right, a broad figure dressed in red holds a noose in one hand, with his gaze directed at Lady Liberty. Looming above him is a hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan.[23]

Among Pippin's work there are many genre paintings, such as the Domino Players (1943), in the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., and several versions of Cabin in the Cotton. Many of these works portray memories from the artist's childhood in Goshen, New York, such as After Supper, West Chester (1935). They depict everyday, domestic activities both outdoors and within the home. At the time of Pippin's youth, prior to the great migrations to come during his adulthood, more than 90 percent of African-Americans resided below the Mason-Dixon line. Consequently, Northern blacks "tended to be relatively invisible to the white masses".[24] Pippin's domestic scenes thus provided a view into black people's lives of which most white patrons would have been ignorant or unaware.[24]

Pippin also created genre paintings that reacted to popular culture. His Cabin in the Cotton series can be connected to a 1932 film of the same name, with Cabin in the Cotton I directly reflecting the composition of the film's opening and closing credit sequences. The artist drew inspiration from a musical source for his painting Old Black Joe, which pictorially expresses the lyrics of Stephen Foster's song by the same name.[25]

Pippin left The Park Bench unfinished in his studio at this death in 1946. Romare Bearden later said: "the man, I think, symbolizes Pippin himself, who, having completed his journey and his mission, sits wistfully, in the autumn of the year, all alone on a park bench."[26]

Collections and retrospective exhibitions

Pippin painted about 140 works, many in museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, N.Y.; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA; the Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania; the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA.

Pippin was the first African American artist to be the subject of a monograph, Selden Rodman's Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America of 1947.[28] He has since been the subject of three major retrospective exhibitions and catalogues since his death:

- Horace Pippin. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., February 25–March 1977; Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, April 5–30, 1977; and Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pa., June 4–September 5, 1977.

- I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, January 21–April 17, 1994; Art Institute of Chicago, April 30–July 10, 1994; Cincinnati Art Museum, July 28–October 9, 1994; Baltimore Museum of Art, October 26, 1994 – January 1, 1995; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 1–April 30, 1995.

- Horace Pippin: The Way I See It. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., April 25–July 19, 2015

Notes

- "Horace Pippin - Pennsylvania Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- Conn, Steve (1997). "The Politics of Painting: Horace Pippin the Historian". American Studies. 38 (1): 5–26. ISSN 0026-3079. JSTOR 40642856.

- Holmes, Kristin E. "Horace Pippin's last resting site no longer hidden". The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 5, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. New York, NY: Universe Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 0-87663-785-3.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 3. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Forgey, 1977, p. 74.

- Judith Stein. I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. New York, 1993.

- William E. Krattinger (December 2009). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Olivet Chapel". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 58. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- "Pippin, Horace." Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 15, copyright 1991.

- Horace Pippin Notebook and Letters Online at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

- "Horace Pippin memoir of his experiences in World War 1, ca. 1921 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/horace-pippin-memoir-his-experiences-world-war-i-7434. Retrieved April 11, 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 4. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- American folk painters of three centuries. Lipman, Jean; Armstrong, Tom; Whitney Museum of American Art. Hudson Hills Press. 1980. ISBN 0933920059.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Conn, Steve (1997). "The Politics of Painting: Horace Pippin the Historian". American Studies. 38 (1): 6. ISSN 0026-3079. JSTOR 40642856.

- Monahan, Anne (4 February 2020). Horace Pippin, American modern. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-24330-7. OCLC 1111940032.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 59. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 61. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 105. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 132. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. pp. 133, 134. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. pp. 128, 129. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Smith, Jessica T. (February 22, 2019). "Horace Pippin, Mr. Prejudice". Smarthistory. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 142. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Stein, Judith E. (1993). I tell my heart : the art of Horace Pippin. West, Cornel,, Wilson, Judith,, Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe,, Powell, Richard J., 1953-, Bockrath, Mark,, Buckley, Barbara. New York, NY. p. 147. ISBN 0-87663-785-3. OCLC 28148136.

- Bearden, Romare (1977). Horace Pippin. Washington, D.C: The Phillips Collection.

- "Barnes Takeout: Art Talk on Horace Pippin's Supper Time". Barnes Foundation. 2 April 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Rodman, Selden (1947). Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America. New York: Quadrangle Press.

Sources

- Forgey, Benjamin, "Horace Pippin's 'personal spiritual journey'", ARTnews 76 (Summer 1977): pp. 74-xx

- "Pippin, Horace." Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 15, copyright 1991. Grolier Inc., ISBN 0-7172-5300-7

- Barnes, Albert. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin Exhibition, Carlen Gallery. Philadelphia, 1940.

- Bearden, Romare. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin, The Phillips Collection. Washington, D.C., 1976.

- Conn, Steve. "The Politics of Painting: Horace Pippin the Historian", American Studies (Spring 1997): pp. 5–26

- Locke, Alain. "Horace Pippin." In Horace Pippin Memorial Exhibition, The Art Alliance, April 8–May 4, 1947. Philadelphia, 1947.

- Monahan, Anne. Horace Pippin, American Modern. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Rodman, Selden. Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America. New York, 1947.

- Judith E. Stein (1993). "I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin". Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015 – via http://judithestein.com.

Further reading

- Bernier, Celeste-Marie. Suffering and Sunset: World War I in the Art and Life of Horace Pippin. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2015.

- Bryant, Jen. A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin. New York, 2013.

- Horace Pippin: The Way I See It, exh. cat. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., 2015

- I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin, exh. cat. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1993.

- Monahan, Anne. Horace Pippin, American Modern. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

External links

- Horace Pippin links

- Horace Pippin Notebook and Letters Online at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art