Hope Theatre

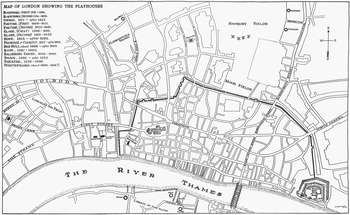

The Hope Theatre was one of the theatres built in and around London for the presentation of plays in English Renaissance theatre, comparable to the Globe, the Curtain, the Swan, and other famous theatres of the era.[2]

..png)

The Hope was built in 1613–14 by Philip Henslowe and a partner, Jacob Meade, on the site of the old Beargarden on the Bankside in Southwark, on the south side of the River Thames — at that time, outside the legal bounds of the City of London. Henslowe had had a financial interest in the Beargarden (the ring for bear-baiting and similar "animal sports") since 1594; on 29 August 1613 he contracted with the carpenter Gilbert Katherens to tear down the Beargarden, and to build a theatre in its place, for a fee of £360. (After the Hope was built, it was often still called the "Beargarden" in common parlance and in the extant documentary record.)

Construction was slow, taking over a year. The Hope may have been delayed because the Globe was being rebuilt at the same time — it had burned down on 29 June 1613 — and two such large jobs, done simultaneously, may have taxed the personnel and resources of the "construction industry" of Southwark, such as it was at the time. (The Hope was located just to the northwest of the Globe, so that the two projects could have competed directly for men and material.) Also, the Hope was likely a more complex construction job, since it was designed as a dual-purpose facility from the start. The contract calls for a:

- Plaiehouse fitt & convenient in all thinges, bothe for players to playe in, and for the game

- of Beares and Bulls to be bayted in the same, and also a fitt and convenient Tyre house and

- a stage to be carryed and taken awaie, and to stande vppon tressels....

So, the Hope would have required facilities for keeping animals that the Globe did not need.

Because Henslowe's original contract with Katherens survives, we know something about the specifics of the construction of the Hope, more so than for other theatres of the period. The contract states that the Hope must be built according to the pattern of the Swan, with two staircases on the outside, and the "heavens" built over the stage, without posts or supports on the stage to disrupt the audience's view — a somewhat different concept from current ideas about the theatres of the period. (The Hope's stage had to be removable, to make room for the "Beares and Bulls.")

The Hope was completed and opened to the public in October 1614. On 31 October, Ben Jonson's Bartholomew Fair was acted in the Hope by the Lady Elizabeth's Men. In the printed text of his play, Jonson describes the Hope as being "as dirty as Smithfield and stinking every whit" — Smithfield being the district of London dominated by the livestock market and slaughterhouses.

On Henslowe's death in 1616, his son-in-law Edward Alleyn inherited Henslowe's share in the Hope, which Alleyn then leased to Meade. The Hope remained an active facility for the coming decades. In its early years the Hope was used more for playing than animal baiting — the days devoted to dramas outnumbered those devoted to animal sports by three to one. Lady Elizabeth's Men were joined by Prince Charles's Men around 1615; when the Lady Elizabeth's company left to tour the provinces in 1616, Prince's Charles's Men remained for another three years. Yet the mix of the two activities was never easy, and the actors grew more unhappy with the arrangements at the Hope as time went on. The actors left for the Cockpit Theatre in 1619, and the Hope was thereafter used for bear and bull baiting, prizefighting, fencing contests, and similar entertainments.

The Corporation of London outlawed both play-acting and bear-baiting at the start of the English Civil War in 1642. Animal sports were suppressed by the Puritan regime in 1656. The last seven surviving bears were shot to death by a company of soldiers; the dogs and the cocks kept there were also killed.[3] (The Commonwealth commander Thomas Pride was responsible for this action; in 1680 — 24 years after the bears' deaths, and 22 years after Pride's — an anonymous satirist composed Pride's confessional Last Speech...being touched in Conscience for his inhuman Murder of the Bears in the Beargarden.)[4]

By one (questionable) account, the Hope Theatre was "pulled down to make tenements, by Thomas Walker, a petticoat maker in Canon Street," on Tuesday, 25 March 1656.[5] Yet the practice of animal sports resumed at the Restoration in 1660; if the Hope had been torn down, a replacement facility was soon established. The Diary of Samuel Pepys records a visit Pepys and his wife made to the Beargarden on 14 August 1666.[6] The last word of animal sports at the facility dates from 12 April 1682. By 1714, a development called Bear Garden Square had been built on the site of the old Hope.

Notes

- Cooper, Tarnya, ed. (2006). "A view from St Mary Overy, Southwark, looking towards Westminster, c.1638". Searching for Shakespeare. London: National Portrait Gallery. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-300-11611-3.

- Halliday, pp. 231-2.

- Durston, p. 157.

- McMains, p. 223 n. 7.

- Manuscript addition to the 1631 edition of Stow and Howes's Chronicle, quoted in Halliday, p. 232, and Wheatley, Vol. 2, pp. 229-30. The addition contains errors. It states that the Hope was built in 1610. Thomas Walker was the master of The Clink Prison.

- Halliday, p. 56.

References

- Durston, Christopher. Cromwell's Major Generals: Godly Government During the English Revolution. Manchester, Manchester University press, 2001.

- Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. Third edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964.

- McMains, H. F. The Death of Oliver Cromwell. Lexington, KY, University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin. London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. 3 Volumes, London, Scribner & Welford, 1891.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hope Theatre. |

- Shakespearean Playhouses, by Joseph Quincy Adams, Jr. from Project Gutenberg

- The Borough of Southwark.