Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: Corpus Hippocraticum), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. Even though it is considered as a singular corpus that represents Hippocratic medicine, they vary (sometimes significantly) in content, age, style, methods, and views practiced; therefore, authorship is largely unknown.[1] Hippocrates began society's development of medicine, through a delicate blending of the art of healing and scientific observations.[1] The Hippocratic Corpus became the foundation for which all future medical systems would be built.[2]

Authorship, name, origin

Of the texts in the corpus, none is proven to be by Hippocrates himself.[3] The works of the corpus range from Hippocrates' time and school to many centuries later and rival points of view. Franz Zacharias Ermerins identifies the hands of at least nineteen authors in the Hippocratic Corpus.[4] However, the varied works of the corpus have gone under Hippocrates' name since antiquity.

The corpus may be the remains of a library of Cos, or a collection compiled in the third century BC in Alexandria. However, the corpus includes works beyond those of the Coan school of Ancient Greek medicine; works from the Cnidian school are included as well.[5][6]

Only a fraction of the Hippocratic writings have survived. The lost medical literature is sometimes referred to in the surviving treatises, as at the beginning of Regimen.[7] Some Hippocratic works are known only in translation from their original Greek to other languages; given that the quality and accuracy of a translation without a suriving original cannot be known, it is difficult to identify the author with certainty. "Hippocratic" texts survive in Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac, and Latin.

Dates and groupings

The majority of the works in the Hippocratic Corpus date from the Classical period, the last decades of the 5th century BC and the first half of the 4th century BC. Among the later works, The Law, On the Heart, On the Physician, and On Sevens are all Hellenistic, while Precepts and On Decorum are from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.[7]

Some of the earliest works of the corpus (mid-fifth century) are connected to the Cnidian school: On Diseases II–III and the early layer within On the Diseases of Women I–II and On Sterile Women.[8] Prorrhetics I is also mid-fifth century.[8] In the second half of the fifth century, a single author likely produced the treatises On Airs, Waters, Places; Prognostics; Prorrhetics II; and On the Sacred Disease.[8] Other fifth-century works include On Fleshes, Epidemics I and III (c. 410 BC), On Ancient Medicine, On Regimen in Acute Diseases, and Polybus' On the Nature of Man/Regimen in Health (410–400 BC).[8]

At the end of the fifth or the beginning of the fourth century, one author likely wrote Epidemics II–IV–VI and On the Humors. The coherent group of surgical treatises (On Fractures, On Joints, On Injuries of the Head, Surgery, Mochlicon) is of similar date.[8]

The gynecological treatises On the Nature of the Woman, On the Diseases of Women, Generation, On the Nature of the Child, and On Sterile Women constitute a closely related group. Hermann Grensemann identified five layers of material in this group, from the mid-fifth century to the mid-fourth century.[9] The oldest stratum is found in On the Nature of the Woman and On the Diseases of Women II.[9] Generation and On the Nature of the Child constitute a single work by a late-fifth-century author,[10] who may also be identified as the author of On Diseases IV and of sections of On the Diseases of Women I.[10] The latest layer is On Sterile Women, which was composed after the other gynecological treatises were in existence.[9]

A single fourth-century author probably wrote On Fistulae and On Hemorrhoids.[8]

Content

The Hippocratic Corpus contains textbooks, lectures, research, notes and philosophical essays on various subjects in medicine, in no particular order.[3][11] These works were written for different audiences, both specialists and laymen, and were sometimes written from opposing view points; significant contradictions can be found between works in the Corpus.[12]

Case histories

One significant portion of the corpus is made up of case histories. Books I and III of Epidemics contain forty-two case histories, of which 60% (25) ended in the patient's death.[13] Nearly all of the diseases described in the Corpus are endemic diseases: colds, consumption, pneumonia, etc.[14]

Theoretical and methodological reflections

In several texts of the corpus, the ancient physicians develop theories of illness, sometimes grappling with the methodological difficulties that lie in the way of effective and consistent diagnosis and treatment. As scholar Jouanna Jacques writes, "One of the great merits of the physicians of the Hippocratic Corpus is that they are not content to practice medicine and to commit their experience to writing, but that they have reflected on their own activity".[15]

Reason and experience

While the approaches range from empiricism to a rationalism reminiscent of the physical theories of the pre-Socratic philosophers, these two tendencies can exist side-by-side: "The close association between knowledge and experience is characteristic of the Hippocratics," despite "the Platonic attempt to drive a wedge between the two".[16]

The author of On Ancient Medicine launches immediately into a critique of opponents who posit a single "cause in all cases" of disease, "having laid down as a hypothesis for their account hot or cold or wet or dry or anything else they want".[17] The method put forward in this treatise "could certainly be characterized as an empirical one", preferring the effects of diet as observed by the senses to cosmological speculations, and it was seized upon by Hellenistic Empiricist doctors for this reason.[18] However, "unlike the Empiricists, the author does not claim that the doctor's knowledge is limited to what can be observed by the senses. On the contrary, he requires the doctor to have quite extensive knowledge of aspects of the human constitution that cannot be observed directly, such as the state of the patient's humors and internal organs".[19]

Epistemology and the scientific status of medicine

The author of The Art is at pains to defend the status of medicine as an art (techne), against opponents who (perhaps following Protagoras' critique of expert knowledge[20]) claim it produces no better results against disease than chance (an attack served by the fact that doctors refused to treat the serious and difficult cases they judged to be incurable by their art[21]). The treatise may be considered "the first attempt at general epistemology bequeathed to us by antiquity", although this may only be because we have lost fifth-century rhetorical works that took a similar approach.[22]

For this writer, as for the author of On the Places in Man, the art of medicine has been wholly discovered. While for the author of On the Places in Man "the principles discovered in it clearly have very little need of good luck", the author of The Art acknowledges the practical limitations that arise in the therapeutic application of these principles.[23] Likewise for the author of On Regimen, the "knowledge and discernment of the nature of man in general—knowledge of its primary constituents and discernment of the components by which it is controlled" may be completely worked out, and yet in practice it is difficult to determine and apply the correct and proportionate diet and exercise to the individual patient.[24]

Natural vs. divine causality

Whatever their disagreements, the Hippocratic writers agree in rejecting divine and religious causes and remedies of disease in favor of natural mechanisms. Thus On the Sacred Disease considers that epilepsy (the so-called "sacred" disease) "has a natural cause, and its supposed divine origin is due to men's inexperience and to their wonder at its peculiar character." An exception to this rule is found in Dreams (Regime IV), in which prayers to the gods are prescribed alongside more typically Hippocratic interventions. Though materialistic determinism goes back in Greek thought at least to Leucippus, "One of the greatest virtues of the physicians of the Hippocratic Collection is to have stated, in its most universal form, what was later to be called the principle of determinism. All that occurs has a cause. It is in the treatise of The Art that the most theoretical statement of this principle is to be found: 'Indeed, under a close examination spontaneity disappears; for everything that occurs will be found to do so through something [dia ti].'"[25] In a famous passage of On Ancient Medicine, the author insists on the importance of knowledge of causal explanations: "It is not sufficient to learn simply that cheese is a bad food, as it gives a pain to one who eats a surfeit of it; we must know what the pain is, the reasons for it [dia ti], and which constituent of man is harmfully affected."[25]

Medical ethics and manners

The duties of the physician are an object of the Hippocratic writers' attention. A famous maxim (Epidemics I.11) advises: "As to diseases, make a habit of two things—to help, or at least to do no harm."

The most famous work in the Hippocratic Corpus is the Hippocratic Oath, a landmark declaration of medical ethics. The Hippocratic Oath is both philosophical and practical; it not only deals with abstract principles but practical matters such as removing stones and aiding one's teacher financially. It is a complex and probably not the work of one man.[26][27] It remains in use, though rarely in its original form.[27]

The preamble of On the Physician offers "a physical and moral portrait of the ideal physician", and the Precepts also concern the physician's conduct.[28] Treatises such as On Joints and Epidemics VI are concerned with the provision of such "courtesies" as providing a patient with cushions during a procedure,[29] and Decorum includes advice on good manners to be observed in the doctor's office or when visiting patients.

Urology within the Hippocratic Corpus

With many books incorporating different urology practices and observations and nearly 30 works in the Hippocratic book collection entitled Aphorism seemingly solely dedicated to urology in general, urology was one subject that was thoroughly investigated.[30] Seemingly, the main and most problematic topic covered in urology was that of bladder disease in patients, especially when urinary tract stones (that is, stones within either the kidneys or the bladder) were present.[30][31] Urinary tract stones, in general, have been seen within records all throughout history, even as far back as the ancient days of Egypt.[31] Theorizing how these urinary tract stones formed, how to detect them and other bladder issues, and the controversy on how to treat them were all major investigating points to the authors of the Hippocratic Corpus.

Stone Formation Theories

Throughout the books of the Hippocratic Corpus, there are varying hypotheses as to reasons why and exactly how urinary tract stones actually formed. It is noted that these hypotheses were all based on the use of uroscopy and observation of patients by doctors of the time.[30]

- Within the work On the Nature of Man, suggest that the bladder stones first form within or attached to the aorta, much like any other tumor-like object would. In this place, the stone will essentially form pus. Afterward, this stone formation is transported by the blood vessels and forced into the bladder where urine will also be transported.[30]

- In another work, On Airs, Waters, Places, it is suggested that drinking water can attribute to urinary tract stones. If water consumed consists of a mixture of more than one water sources, the water is of impure quality. The different waters are in conflict with one another and therefore produce deposits of sediment. The accumulation of these deposits within the urinary tract due to drinking the waters can then result in urinary tract stones.[30]

- Additionally in On Airs, Waters, Places, another passage describes that formation of urinary tract stones will occur when urine cannot flow through the system easily and causes the sediment in the urine to collect in one area and meld, forming a stone. This can occur when inflammation occurs within the part of the bladder leading to the urethra. When the stone forms at this point, it can block flow and, therefore, cause pain. In this scenario, it was hypothesized that males are more likely to form stones than females due to the anatomy of the bladder.[30]

Detecting Bladder Disease/Stones

The main mechanism of detecting bladder disease’s symptoms, including inflammation and urinary tract stone formations, is through the appearance of the urine itself and the changes that occur with the urine over time.[30] In Aphorism, it was simply stated that as the appearance of urine diverges more and more from the appearance of “healthy” urine, the more likely it is to be diseased and the worse the disease becomes.[30]

In Aphorism works, it was noted that urine lacking color could indicate diseases of the brain – some today think that this author who made this statement was meaning to refer to chronic renal failure or even diabetes. It was also suggested that the appearance of blood within urine could indicate vessels of the kidney to have burst, potentially due to necrosis of blood arteries or vessels. Furthermore, doctors noted that if bubbles formed on top of urine, the kidneys were diseased and showed the potential of long-lasting disease.[30]

Treatment of Bladder Disease/Stones

When it comes to the treatment of urinary tract stones, many solutions were suggested, including drinking a lot of a water/wine mixture, taking strong medication, or trying different positions when trying to flush them out.[30][31]

Extracting the urinary tract stones was another option; however, this method was not utilized very often due to its serious risks and possible complications of cutting into the bladder.[32] Other than leakage of urine into the body cavity, another common complication was that of the cells of the testes dying due to the spermatic cord inadvertently being cut during the procedure.[30][33]

In fact, due to these and other complications and the lack of antiseptics and pain medicines, the Hippocratic Oath opted for the avoidance of surgery – unless absolutely necessary – especially when concerning surgeries that dealt with the urinary tract and more so when stone removal was the intent.[30][31][32] Although, the urinary tract stone removal was not a necessary surgery and it appeared to be avoided in most cases, some argue that the Hippocratic Oath only wards of these procedures if the doctor holding the knife is inexperienced in that area.[30][33] This idea puts forth the development of medical specialties – that is, doctors focusing on one particular area of medicine versus studying the wide array of material that is medicine.[30][31] The doctors whom have become experts in the urinary tract – whom we would call urologists today – are those that could perform the heightened risk procedure of stone removal.[30][31][33] With this reliance on specialized doctors of the urinary tract, some believe that urology itself was the first definable expertise of medical history.[31][33]

.jpg)

Wine within the Hippocratic Corpus

References to wine can be found throughout Greek antiquity in both dramas and medical texts.[34] The Hippocratic texts describe wine as a powerful substance, that when consumed in excess can cause physical disorders, today known as, intoxication. Although the negative effects of wine on the human body are documented within the Hippocratic Corpus, the author/authors maintain an objective attitude towards wine. During this time, those studying medicine were interested in the physical effects of wine, therefore no medical text condemned the use of wine in excess. According to the Hippocratic text, the consumption of wine significantly affects two regions of the body: the head and the lower body cavity.[34] Excessive drinking can cause heaviness of the head and pain in the head, in addition to disturbances in thought. In the lower body cavity, excess wine ingestion can have a purging effect; it can be the source of stomach pain, diarrhea, and vomiting.[34] An overall effect of wine that all Greek doctors of the time have observed and agree on is its warming property. Therefore, wine’s properties are described as “hot and dry.”[34] As documented in the Hippocratic texts, extreme use of wine can result in death.

Physicians tried to study the human body with pure objectivity to give the most accurate explanation for the effects of external substances that could be given for the time. During this period, physicians believed not all wines were equally potent in producing a range of perilous symptoms. According to the Hippocratic texts, physicians carefully categorized wine by properties such as color, taste, viscosity, smell, and age. According to Hippocrates, a more concentrated wine leads to a heavy head and difficulty thinking, and a soft wine inflames the spleen and liver and produces wind in the intestine.[34] Other observations of the ingestion of wine included the varying levels of tolerance within the population being observed. This observation led to the belief that the size of your body and your environment had an influence on your ability to handle wine.[34] Physician’s also hypothesized that gender contributed to the effects of wine on the body. It was not common practice between physicians of the time to recommend the consumption of wine for children. Physician’s collectively believed that there was no purpose for children to drink wine. However, in rare circumstances, there are records of some doctors recommending wine for children, only if heavily diluted with water, to warm the child or to ease hunger pains.[34] Mostly, doctors prohibited wine consumption for people under eighteen.

Greek physicians were very interested in observing and recording the effects of wine and intoxication, the excessive use of wine was well known to be harmful, however, it was also documented as a useful remedy. Several of the Hippocratic texts list the properties and use of foods consumed during 5th century BC.[34][35] Wine was first defined as a food by all doctors. Directions for consumption varied based on gender, season, and other events in daily life. Men were encouraged to consume dark, undiluted wine before copulation, not to the point of intoxication, however enough to provide power and guarantee strength to the fetus.[34] Because of wine's visual similarity to blood, physicians had assumed a relationship between the two substances. For this reason, men suffering from cardiac illness, lack of strength, or pale complexion were encouraged to consume dark, undiluted wine.[34] Multiple texts within the Hippocratic Corpus advise the use of wine in accordance with the seasons. During the winter, wine must be undiluted, to counter the cold and wet, because wine’s properties are dry and hot. During fall and spring, wine should be moderately diluted, and during the summer, wine should be diluted as much as possible with water, because of the hot temperatures. The practice of mixing wine and diluting wine is also seen in prescription form, however, the dosage and quantities are left to the doctor.[34] The prescription of wine as a treatment was prohibited with diseases that affected the head, brain, and those accompanied by a fever.[34] Wine could also be used as an external remedy by mixing it with other substances such as honey, milk, water, or oil to make salves or soaks.[36] Patients suffering from pneumonia like illnesses would soak in a wine mixture and breath in the vapors with the intent to expel the pus from their lungs.[36] Wine was frequently prescribed as a topical remedy for sores because of its drying effect.[35]

Epidemics 1

In Epidemics 1, it begins by describing each season’s characteristics. The season autumn; described by strong south winds and many rainy days. Winter had south winds with the occasional north wind, and droughts. Spring was southerly and cold with slight rain. Summer was cloudy and didn’t rain.[37] Starting in the spring, many people began having mild fevers and in some, it caused hemorrhage. The hemorrhage was rarely fatal and only accounts for very few deaths. Swelling next to both ears was also a common occurrence. Coughs and sore throats accompanied the other symptoms.[38] Based on modern knowledge about various diseases, it is clear that the swelling next to the ears was mumps. This is known because mumps causes swollen salivary glands that are located under the ears and the descriptions in the Hippocratic Corpus were so vivid that even over a thousand years later, the symptoms could be identified.[39] The fever and cough can simply be associated with allergies or the common cold, although it cannot be for certain. Epidemics 1 goes on to describe the climate in two different occasions with the illnesses associated with them, called Constitutions. Some of the symptoms include more serious, sometimes lethal fevers, eye infections, and dysentery.[37]

On Diseases

Jaundice is a disease that is mentioned numerous times throughout and is described as occurring in five different ways. Jaundice is when the skin or eyes turn yellow.[40] The Greek physicians thought of Jaundice to be a disease itself rather than what medical professionals know now to be a symptom of various other diseases. The Greeks also believed that there were five different kinds of jaundice that can occur and report the differences between them.[41]

The first kind can quickly turn fatal. The skin appears to be green. The analogy made in the text is that the skin is greener than a green lizard.[41] The patient will have fevers, shiver, and the skin becomes very sensitive. In the mornings, sharp pains occur in the abdominal region. If the patient survives more than two weeks, they have a chance of recovery. The treatments suggest drinking a mixture of milk and other nuts and plants in the morning and at night.[41] The second form develops only during the summer because it was believed the heat of the sun causes bile, a dark green fluid produced by the liver, to rest underneath the skin. This causes a yellowish color to the skin, and pale eyes and urine. The scalp also develops a crusty substance. The treatment calls for several baths a day on top of the mixture mentioned in the first remedy. Surviving past two weeks with this form of jaundice was rare.[41] In two other forms of this disease, occurring during the winter, set in due to drunkenness, chills, and the excess production of phlegm. The last form is the least fatal and most common. It is associated with eating and drinking too much. The symptoms include yellow eyes and skin, fever, headache, and weakness.[41] The treatment however, it very different from the rest. The physician will draw blood from the elbows, and advise to take hot baths, drink cucumber juice, and induce vomiting to clear the bowels. If the treatment is followed, a full recovery is possible.[42] The several forms of jaundice that the Greek physicians proclaimed might be because jaundice occurs due to varying sicknesses like hepatitis, gallstones and tumors. The diverse set of symptoms were probably the effects of the sicknesses rather than the jaundice itself.

Empyemas in the Hippocratic Corpus

An empyema is a Greek word derived from the word “empyein” which means “pus-producing.”[43] According to the Hippocratic Corpus, they can occur in the thorax, the uterus, the bladder, the ear, and other parts of the body.[44] However, the writings indicate that the thorax was the most common and provided more description. Physicians at the time thought that the cause of an empyema was by orally ingesting some form of foreign body where it will enter the lungs. This could be done by inhaling or drinking the foreign body. The physicians also thought that empyemas could occur after parapneumonic infections or pleurisy because the chest has not recovered from those illnesses.[44] Parapneumonic infections can be tied to modern pneumonia which can still be fatal.

There are many symptoms associated with an empyema ranging from mild to severe. The most common ones are fever, thoracic pain, sweating, heaviness in the chest, and a cough.[44] Treating an empyema was primarily done using herbal remedies or non-invasive treatments. Mostly mixtures of different plants and organic matter were drank or bathed in. There are a few extreme cases in which invasive procedures were performed and mentioned in detail. One of these treatments included the patient behind held down in a chair while the physician cut between the ribs with a scalpel and inserted a drainage tube which would remove all of the pus.[44] The research and descriptions that the Greek physicians performed were so accurate that they were the foundation of what we know about empyemas today.

Style

The writing style of the Corpus has been remarked upon for centuries, being described by some as, "clear, precise, and simple".[45] It is often praised for its objectivity and conciseness, yet some have criticised it as being "grave and austere".[46] Francis Adams, a translator of the Corpus, goes further and calls it sometimes "obscure". Of course, not all of the Corpus is of this "laconic" style, though most of it is. It was Hippocratic practice to write in this style.[47]

The whole corpus is written in Ionic Greek, though the island of Cos was in a region that spoke Doric Greek.

The Art and On Breaths show the influence of Sophistic rhetoric; they "are characterized by long introductions and conclusions, antitheses, anaphoras, and sound effects typical of Gorgianic style". Other works also have rhetorical elements.[48] In general, it can be said that "the Hippocratic physician was also an orator", with his role including public speeches and "verbal wrestling matches".[49]

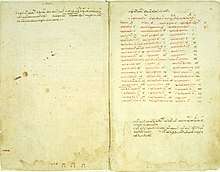

Printed editions

The entire Hippocratic Corpus was first printed as a unit in 1525. This edition was in Latin and was edited by Marcus Fabius Calvus in Rome. The first complete Greek edition followed the next year from the Aldine Press in Venice. A significant edition was that of Émile Littré who spent twenty-two years (1839–1861) working diligently on a complete Greek edition and French translation of the Hippocratic Corpus. This was scholarly, yet sometimes inaccurate and awkward.[50] Another edition of note was that of Franz Zacharias Ermerins, published in Utrecht between 1859 and 1864.[50] Kühlewein's Teubner edition (1894–1902) "mark[ed] a distinct advance".[50]

Beginning in 1967, an important modern edition by Jacques Jouanna and others began to appear (with Greek text, French translation, and commentary) in the Collection Budé. Other important bilingual annotated editions (with translation in German or French) continue to appear in the Corpus medicorum graecorum published by the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

English translations

The first English translation from the Hippocratic Corpus, Peter Lowe's Chirurgerie ("Surgery"), was published in 1597, but a complete English translation of a dozen and a half "genuine" works was not offered in English until Francis Adams' publication of 1849. Other works of the corpus remained untranslated into English until the resumed publication of the Loeb Classical Library edition beginning in 1988.[51] The first four Loeb volumes were published in 1923–1931, and six further volumes between 1988 and 2012.

List of works of the Corpus

(Ordering from Adams 1891, pp. 40–105; LCL = vols. of the Loeb Classical Library edition)

|

|

See also

- Huangdi Neijing, a work of comparable importance in Chinese medicine, published during the same time period

Notes

- Reinventing Hippocrates. Cantor, David. Aldershot, Eng.: Ashgate. 2002. ISBN 978-0754605287. OCLC 46732640.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pavlidis, N.; Karpozilos, A. (2004-09-01). "The treatment of cancer in Greek antiquity". European Journal of Cancer. 40 (14): 2033–2040. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.036. ISSN 1879-0852. PMID 15341975.

- Singer & Underwood 1962, p. 27.

- Tuke 1911, p. 518.

- Margotta 1968, p. 64.

- Martí-Ibáñez 1961, pp. 86–87.

- Gillispie 1972, p. 420.

- Jouanna 1999, pp. 373–416 (Appendix 3: The Treatises of the Hippocratic Collection).

- Hanson 1991, p. 77.

- Lonie 1981, p. 71.

- Rutkow 1993, p. 23.

- Singer & Underwood 1962, p. 28.

- Garrison 1966, p. 95.

- Jones 1923, p. lvi.

- Jouanna 1988, p. 83.

- Schiefsky 2005, p. 117.

- On Ancient Medicine 1.1, trans. Schiefsky 2005, p. 75

- Schiefsky 2005, pp. 65–66.

- Schiefsky 2005, p. 345.

- Jouanna 1999, p. 244.

- Jouanna 1999, p. 108.

- Jouanna 1999, pp. 246–248, 255–256.

- Jouanna 1999, p. 238.

- Regimen 1.2 (Jones 1959, pp. 227–229)

- Jouanna 1999, pp. 254–255.

- Jones 1923, p. 291.

- Garrison 1966, p. 96.

- Jouanna 1999, pp. 404–405.

- Jouanna 1999, p. 133.

- Poulakou-Rebelakou E, Rempelakos A, Tsiamis C, Dimopoulos C (February 2015). ""I will not cut, even for the stone": origins of urology in the Hippocratic Collection". International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 41 (1): 26–9. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.05. PMC 4752053. PMID 25928507.

- Bloom DA (July 1997). "Hippocrates and urology: the first surgical subspecialty". Urology. 50 (1): 157–9. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00114-3. PMID 9218041.

- Tung T, Organ CH (January 2000). "Ethics in surgery: historical perspective". Archives of Surgery. 135 (1): 10–3. doi:10.1001/archsurg.135.1.10. PMID 10636339.

- Herr HW (September 2008). "'I will not cut . . . ': the oath that defined urology". BJU International. 102 (7): 769–71. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.07796.x. PMID 18647301.

- Jacques, Jouanna (2012-07-25). Greek medicine from Hippocrates to Galen : selected papers. Eijk, Ph. J. van der (Philip J.),, Allies, Neil. Leiden. ISBN 9789004232549. OCLC 808366430.

- M., Craik, Elizabeth (2014). The 'Hippocratic' corpus : content and context. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 9781138021693. OCLC 883647666.

- Papavramidou, Niki; Christopoulou-Aletra, Helen (2008-03-01). ""Empyemas" of the Thoracic Cavity in the Hippocratic Corpus". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 85 (3): 1132–1134. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.031. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 18291225.

- Jones, W. H. S. (1923). Hippocrates, with and English Translation by W. H. S. Jones. London: Heinemann. pp. 147–150, 472–473.

- Craik, Elizabeth M. (2015). The 'Hippocratic' corpus : content and context. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-138-02169-3. OCLC 883647666.

- "Mumps | Home | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- "Jaundice". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Papavramidou, Niki; Fee, Elizabeth; Christopoulou-Aletra, Helen (2007-11-13). "Jaundice in the Hippocratic Corpus". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 11 (12): 1728–1731. doi:10.1007/s11605-007-0281-1. ISSN 1091-255X. PMID 17896166.

- Nutton, Vivian. (2004). Ancient medicine. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08611-6. OCLC 53038721.

- "Definition of Empyema". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Christopoulou-Aletra, Helen; Papavramidou, Niki (March 2008). ""Empyemas" of the Thoracic Cavity in the Hippocratic Corpus". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 85 (3): 1132–1134. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.031. PMID 18291225.

- Garrison 1966, p. 99.

- Jones 1923, p. xv.

- Adams 1891, p. 18.

- Schironi 2010, p. 350.

- Jouanna 1999, p. 79–85.

- Jones 1923, pp. lxviii–lxix.

- Vivian Nutton, review of Loeb vols. 5–6 (1988).

- The Coan Prenotions, once thought by Littré and others to be the ancient source of Prognostics, is now universally agreed to be a compilation derivative of Prognostics and other Hippocratic works.(Jouanna 1999, p. 379)

References

- Adams, Francis (1891). The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. New York: William Wood and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1972). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. VI. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 419–427.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garrison, Fielding H. (1966). History of Medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanson, Ann Ellis (1991). "Continuity and Change: Three Case Studies in Hippocratic Gynecological Therapy and Theory". In Pomeroy, Sarah B. (ed.). Women's History and Ancient History. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4310-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lonie, Iain M. (1981). The Hippocratic Treatises "On Generation," "On the Nature of the Child," "Diseases IV". Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, W.H.S (1923). General Introduction to Hippocrates. Loeb Classical Library. 1. Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, W.H.S (1959). Hippocrates with an English translation by W. H. S. Jones. Loeb Classical Library. 4. Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jouanna, Jacques (1988). Hippocrate: Oeuvres complètes. Collection Budé. 5 (part 1). p. 83. ISBN 978-2-251-00396-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jouanna, Jacques (1999). Hippocrates. Translated by DeBevoise, M.B. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP. ISBN 978-0-8018-5907-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Margotta, Roberto (1968). The Story of Medicine. New York: Golden Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martí-Ibáñez, Félix (1961). A Prelude to Medical History. New York: MD Publications, Inc. Library of Congress ID: 61–11617.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rutkow, Ira M. (1993). Surgery: An Illustrated History. London and Southampton: Elsevier Science Health Science div. ISBN 978-0-801-6-6078-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schiefsky, Mark J (2005). Hippocrates: On Ancient Medicine. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13758-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schironi, Francesca (2010). "Technical Languages: Science and Medicine". In Bakker, Egbert J. (ed.). A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-4051-5326-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singer, Charles; Underwood, E. Ashworth (1962). Short History of Medicine. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Library of Congress ID: 62–21080.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tuke, John Batty (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 517–519.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hippocrates. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hippocratic Corpus |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Hippocrates |

English translations and Greek/English bilingual editions

- Loeb edition (1923–1931): vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4

- Hippocrates: Greek texts and English translations from the Perseus Project

- English translations by Francis Adams: HTML anthology; 1891 edition via Harvard; earlier editions

Other Greek texts

Bibliography

- Gerhard Fichtner, Hippocratic bibliography (2011) (Berlin Academy)