Hexaplex trunculus

Hexaplex trunculus (also known as Murex trunculus, Phyllonotus trunculus, or the banded dye-murex) is a medium-sized sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Muricidae, the murex shells or rock snails.

| Hexaplex trunculus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hexaplex trunculus | |

| |

| Hexaplex trunculus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Subgenus: | Trunculariopsis[1] |

| Species: | H. trunculus |

| Binomial name | |

| Hexaplex trunculus | |

| Synonyms | |

This species is a group of opportunist predatory snails that are known to attack their prey in groups. What is peculiar about this specific species is that they show no preference for the size of their prey, regardless of their hunger levels.[2]

The snail appears in fossil records dating between the Pliocene and Quaternary periods (between 3.6 and 0.012 million years ago). Fossilized shells have been found in Morocco, Italy, and Spain.[3]

This sea snail is historically important because its hypobranchial gland secretes a mucus used to create a distinctive purple-blue indigo dye. Ancient Mediterranean cultures, including the Minoans, Canaanites/Phoenicians, Hebrews, and classical Greeks created dyes from the snails. One of the dye's main chemical ingredients is red dibromo-indigotin, the main component of tyrian purple.[4] The dye will turn indigo blue, similar to the color of blue jeans, if exposed to sunlight before the dye sets. Indigo dye produced in this manner is known as Tekhelet.[5]

Distribution

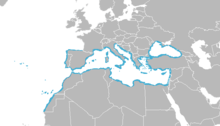

This species lives in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa, specifically Spain, Portugal, Morocco, the Canary Islands, Azores.[1] This murex occurs in shallow, sublittoral waters.

Shell description

Hexaplex trunculus has a broadly conical shell about 4 to 10 cm long. It has a rather high spire with seven angulated whorls, and the shell is formed similar to the shape of a fish. The shell is variable in sculpture and coloring with dark banding, in four varieties. The ribs sometimes develop thickenings or spines and give the shell a rough appearance. The shell is often covered in algae, which camouflages it, making it appear very similar to the seabed.

Apertural view of a shell

Apertural view of a shell.jpg) Dorsal view of a shell

Dorsal view of a shell Hexaplex Trunculus camouflaged in microalgae

Hexaplex Trunculus camouflaged in microalgae- Fossil shell of Hexaplex trunculus conglobatus from Pliocene

Human use

Snail secretions were used as dye in ancient times. People still eat the snail in Portugal.[6]

As ancient dye

The purple dye originated in Phoenician colonies. The Phoenician port cities on the coast of current-day Lebanon, exported the dye across the Mediterranean.

The ancient method for mass-producing purple-blue dye from Hexaplex trunculus has not been successfully reproduced; the purplish hue quickly degrades, resulting in blue only. Nonetheless, archeologists have confirmed Hexaplex trunculus as the species used to create the purple-blue dye; large numbers of shells were recovered from inside ancient live-storage chambers that were used for harvesting. Apparently, 10- to 12,000 murex yielded only one gram of dye. Because of this, the dye was highly prized. Also known as Royal Purple, it was prohibitively expensive and was only used by the highest ranking aristocracy.

A similar dye, Tyrian purple, which is purple-red in color, was made from a related species of marine snail, Murex brandaris. This dye (alternatively known as imperial purple, see purple) was also prohibitively expensive.

Jews may have used the pigment from the shells to create a sky-blue, tekhelet, dye to put on the fringes that the Torah specifies for the corner of the prayer shawl. This blue dye would have been made by taking the yellow dye solution and letting it sit in the sunlight, and then dipping the wool in it. This dye was lost to history until it was rediscovered by Professor Otto Elsner of the Shenkar College of Fibers in Haifa. Since then, it has been re-introduced as the authentic tekhelet and has once again been reenstated to the Jewish garment [7] although only with limited acceptance.

References

- Houart, R.; Gofas, S. (2009). "Hexaplex trunculus (Linnaeus, 1758)". In Bouchet, P.; Gofas, S.; Rosenberg, G. (eds.). World Marine Mollusca Database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- Guler, Mehmet; Lok, Aynur (2019). "Foraging Behaviors of a Predatory Snail (Hexaplex trunculus) in Group-Attacking". Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 19 (5): 391–398. doi:10.4194/1303-2712-v19_5_04. ISSN 1303-2712.

- Fossilworks

- Radwin, G. E.; D'Attilio, A. (1986). Murex shells of the world. An illustrated guide to the Muricidae. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 93. 284 pp incl 192 figs. & 32 pls.

- Navon, Mois (December 30, 2013). "Threads of Reason-A Collection of Essays on Tekhelet" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

In 1985, while writing a book about Tzitzit entitled Kelil Tekhelet, R. Eliyahu Tavger became convinced that the source of authentic Tekhelet had been found. Determined to actualize his newfound knowledge, and after much trial and error, he succeeded in applying the process, according to Halakhah, from beginning to end. He thus became the first person, since the loss of the Ḥillazon, to dye Tekhelet for the purpose of Tzitzit. In 1991, together with R. Tavger, Ptil Tekhelet was formed to produce and distribute Tekhelet strings for Tzitzit.

- Vasconcelos, P.; Carvalho, S.; Castro, M.; Gaspar, M. B. (2008). "The artisanal fishery for muricid gastropods (banded murex and purple dye murex) in the Ria Formosa lagoon (Algarve coast, southern Portugal)". Scientia Marina. 72 (2): 287–298. doi:10.3989/scimar.2008.72n2287.

- http://tekhelet.com/tekhelet/introduction-to-tekhelet/

- Ruppert, E.E., R.S. Fox and R.D. Barnes 2004 Invertebrate Zoology. A functional evolutionary approach. 7th Ed. Brooks/Cole, Thomson Learning learning, Inc. 990 p.

- Templado, J. and R. Villanueva 2010 Checklist of Phylum Mollusca. pp. 148-198 In Coll, M., et al., 2010. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 5(8):36pp

External links

- Photos of Hexaplex trunculus on Sealife Collection