Hemileia vastatrix

Hemileia vastatrix is a fungus of the order Pucciniales (previously also known as Uredinales) that causes coffee leaf rust (CLR), a disease that is devastating to susceptible coffee plantations. Coffee serves as the obligate host of coffee rust, that is, the rust must have access to and come into physical contact with coffee (Coffea sp.) in order to survive. There is no cure at the moment, although farms have managed to reduce their impact by replanting infected farms with hybrids that have a strong genetic resistance to rust.[1]

| Hemileia vastatrix | |

|---|---|

| |

| Symptoms of coffee rust caused by Hemileia vastatrix on foliage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Genus: | Hemileia |

| Species: | H. vastatrix |

| Binomial name | |

| Hemileia vastatrix | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Wardia vastatrix J.F.Hennen & M.M.Hennen (2003) | |

Appearance

The mycelium with uredinia looks yellow-orange and powdery, and appears on the underside of leaves as points ~0.1 mm in diameter. Young lesions appear as chlorotic or pale yellow spots some millimetres in diameter, the older being a few centimetres in diameter. Hyphae are club-shaped with tips bearing numerous pedicels on which clusters of urediniospores are produced.

Telia are pale yellowish, teliospores often produced in uredinia; teliospores more or less spherical to limoniform, 26–40 × 20–30 µm in diameter, wall hyaline to yellowish, smooth, 1 µm thick, thicker at the apex, pedicel hyaline.

Urediniospores are more or less reniform, 26–40 × 18-28 µm, with hyaline to pale yellowish wall, 1–2 µm thick, strongly warted on the convex side, smooth on the straight or concave side, warts frequently longer (3–7 µm) on spore edges.

Spermogonia and aecia are unknown.

Lifecycle

Hemileia lifecycle begins with the germination of uredospores through germ pores in the spore. It mainly attacks the leaves and is only rarely found on young stems and fruit. Appressoria are produced, which in turn produce vesicles, from which entry into the substomatal cavity is gained. Within 24–48 hours, infection is completed. After successful infection, the leaf blade is colonized and sporulation will occur through the stomata. One lesion produces 4–6 spore crops over a 3–5 month period releasing 300–400,000 spores.

While the predominant hypothesis is that H. vastatrix is heteroecious, completing its life cycle on an alternate host plant which has not yet been found, an alternative hypothesis is that H. vastatrix actually represents an early-diverging autoecious rust, in which the teliospores are non-functional and vestigial, and the sexual life cycle is completed by the urediniospores. Hidden meiosis and sexual reproduction (cryptosexuality) has been found within the generally asexual urediniospores.[2] This finding may explain why new physiological races have arisen so often and so quickly in H. vastatrix.

Management

Several different methods can be used to control the presence of Coffee Leaf Rust including culture methods and chemical methods. Understanding that the extended presence of water on the leaves allows Hemileia vastatrix to infect can help decide what can be done to prevent infection. Cultural methods like pruning the branches back to allow more air circulation and light penetration can dry the moisture on the leaves, hindering urediniospore germination, and preventing favorable conditions that the pathogen needs to successfully infect. Planting coffee trees in wide rows and preventing weed growth also allows for more air circulation. The goal is to create an environment that is not conductive to development of the pathogen. The correct amount of fertilizer application can also play a role in host susceptibility.[3] Fertilizating with nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) tends to reduce the susceptibility to rust, but excessive potassium (K) increases susceptibility. There are tradeoffs between growing coffee trees in the shade versus direct sunlight. Growing in the shade decreases the presence of dew on the leaves but moisture that exists on the leaves does not evaporate as fast. Alternatively, growing coffee trees in direct sunlight will evaporate dew faster decreasing the time period the pathogen has to infect with available moisture. Chemical methods for controlling Coffee Leaf Rust are another popular option but have several factors to consider. When deciding what application type and frequency to spray, any given fungicide application has to be considered a long-term investment, with effects not only in the current season but in future seasons as well.[3] Chemical applications, such as a copper based fungicide can be costly and run the risk of pathogens developing ways to get around the fungicide.

Ecology

Hemileia vastatrix is an obligate parasite that lives mainly on the plants of genus Coffea, reportedly also on Gardenia in South Africa.

The rust needs suitable temperatures to develop (between 16 °C and 28 °C).[4] High altitude plantations are generally colder, so inoculum won't develop as easily as in plantations located in warmer regions. The presence of free water is required for infection to be completed. Loss of moisture after germination starts inhibits the whole infection process.

Sporulation is most influenced by temperature, humidity, and host resistance. The colonization process is not dependent on leaf wetness but is influenced greatly by temperature and by plant resistance. The main effect of temperature is to determine the length of time for the colonization process (incubation period).

Hemileia vastatrix has two fungal parasites, Verticillium haemiliae and Verticillium psalliotae.

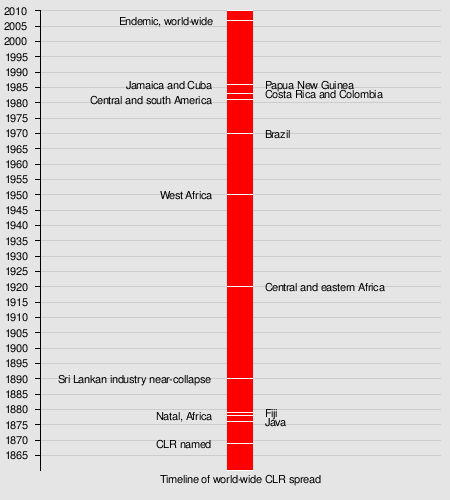

The fungus is of East African origin, but nowadays widely spread in Africa, tropical Asia, and Central and South America. Coffee originates from high altitude regions of Ethiopia, Sudan, and Kenya and the rust pathogen is believed to have originated from the same mountains. The earliest reports of the disease hail from the 1860s. It was reported first by a British explorer from regions of Kenya around Lake Victoria in 1861 from where it is believed to have spread to Asia and the Americas.

Rust was first reported in the major coffee growing regions of Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1867. The causal fungus was first fully described by the English mycologist Michael Joseph Berkeley and his collaborator Christopher Edmund Broome after an analysis of specimens of a “coffee leaf disease” collected by George H.K. Thwaites in Ceylon. Berkeley and Broome named the fungus Hemileia vastatrix, "Hemileia" referring to the half smooth characteristic of the spores and "vastatrix" for the devastating nature of the disease.[5]

It is unknown exactly how the rust reached Ceylon from Ethiopia. Over the years that followed, the disease was recorded in India in 1870, Sumatra in 1876, Java in 1878, and the Philippines in 1889. During 1913 it crossed the African continent from Kenya to the Congo, where it was found in 1918, before spreading to West Africa, the Ivory Coast (1954), Liberia (1955), Nigeria (1962–63) and Angola (1966).

Uredospores are disseminated across long distances mainly by wind and can end up thousands of miles from where they were produced. Over short distances uredospores are disseminated by both wind and rain splash. Other agents such as animals, mainly insects and contaminated equipment, occasionally have been shown to be involved with dissemination.

Pathogenesis

Hemileia vastatrix affects the plant by covering leaf surface area and destroying cell function resulting in a reduction in the rate of photosynthesis. Continuous colonization of the pathogen depletes the plants resources for surviving until the plant no longer has enough energy to grow or survive.[6] Coffee plants bred for resistance succeed because of cytological and biochemical resistance mechanisms. Such mechanisms involve transmitting signals to the infection sight to stop cell function. The plants cell degradation response frequently occurs after the formation of the first haustorium and result in rapid hypersensitive cell death. Because Hemileia vastatrix is an obligate parasite, it can no longer survive when surrounded by dead cells. This can be recognized by the presence of browning cells in local regions on a leaf.[7]

Environment

Temperature and moisture specifically play the largest role in infection rate of the coffee plant. Humidity is not enough to allow infection to occur. There must be a presence of water on the leaf for the urediospores to infect; although, dry urediospores can survive up to 6 weeks without water. Dispersal happens primarily by wind, rain, or a combination of both. Transmission over large distances is likely the result of human intervention by spores clinging to clothes, tools, or equipment. Dispersal by insects is unlikely and therefore insignificant.[8] Spore germination only happens when temperature ranges from 13 to 31 degrees Celsius and peaks at 21 degrees Celsius; furthermore, appressorium formation is highest at 11 degrees Celsius and has a linear decline in production until 32 degrees Celsius when there is little to no production.[9] Although temperature and moisture are key factors for infection, dispersal, and colonization, plant resistance is also important in determining whether Hemileia vastatrix will survive.

History

The disease was first described and named by Berkley and Broom in the November 1869 edition of the Gardeners Chronicle.[10]:171 They used specimens sent from Sri Lanka, where the disease was already causing enormous damage to productivity. Many coffee estates in Sri Lanka were forced to collapse or convert their crops to alternatives not affected by CLR, such as tea.[10]:171–2 The planters nicknamed the disease "Devastating Emily"[11] and it affected Asian coffee production for over twenty years.[12] By 1890 the coffee industry in Sri Lanka was nearly destroyed, although coffee estates still exist in some areas. Historians suggest that the devastated coffee production in Sri Lanka is one of the reasons why Britons have come to prefer tea, as Sri Lanka switched to tea production as a consequence of the disease.[13]

By the 1920s CLR was widely found across much of Africa and Asia, as well as Indonesia and Fiji. It reached Brazil in 1970 and from there it rapidly spread at a rate enabling it to infect all coffee areas in the country by 1975.[10]:171–2 From Brazil, the disease spread to most coffee-growing areas in Central and South America by 1981, hitting Costa Rica and Colombia in 1983.

As of 1990, coffee rust has become endemic in all major coffee-producing countries.[10]:171–2

2012 coffee leaf rust epidemic

In 2012, there was a major increase in coffee rust across ten Latin American and Caribbean countries. The disease became an epidemic and the resulting crop losses led to a fall in supply, outstripping demand. Coffee prices rose as a result, although other factors such as growing demand for gourmet beans in China, Brazil, and India also contributed.[14][15]

The reasons for the epidemic remain unclear but an emergency rust summit meeting in Guatemala in April 2013 compiled a long list of shortcomings. These included a lack of resources to control the rust, the dismissal of early warning signs, ineffective fungicide application techniques, lack of training, poor infrastructure and conflicting advice. In a keynote talk at the “Let’s Talk Roya” meeting (El Salvador, November 4, 2013), Dr Peter Baker, a senior scientist at CAB International, raised several key points regarding the epidemic including the proportional lack of investment in research and development in such a high value industry and the lack of investment in new varieties in key coffee producing countries such as Colombia.[5]

Economic Impact

Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR) has direct and indirect economic impacts on coffee production. Direct impacts include decreased quantity and quality of yield produced by the diseased plant. Indirect impacts include increased costs to combat and control the disease. Methods of combating and controlling the disease include fungicide application and stumping diseased plants and replacing them with resistant breeds. Both methods include significant labor and material costs and in the case of stumping, include a years-long decline in production (coffee seedlings are not fully productive for three to five years after planting).

Due to the complexity of accurately accounting for losses attributed to CLR, there are few records quantifying yield losses. Estimates of yield loss vary by country and can range anywhere between 15-80%. Worldwide loss is estimated at 15%.

Some early data from Ceylon documenting the losses in the late 19th century indicate coffee production was reduced by 75%. As farmers shifted from coffee to other crops not affected by CLR, land used for growing coffee was reduced by 80%, from 68,787 to 14,170 ha.

In addition to the costs mentioned above, additional costs include research and development costs in producing resistant cultivars. These costs are normally borne by the industry, local and national governments and international aid agencies.[10]:174

Colombia's National Federation of Coffee Growers (Fedecafe) set up a research lab specifically designed to find ways to stop the disease, as the country is a leading exporter of the Coffea arabica bean that is particularly prone to the disease.[13]

Disease reports

Coffee crops in Guatemala have been ruined by coffee rust, and a state of emergency has been declared in February 2013.[16][17]

CLR has been a problem in Mexico.[18]

CLR disease is a big problem in coffee plantations in Peru, declared in sanitary emergency by government (Decreto Supremo N° 082-2013-PCM).

References

- "Coffee Rust Threatens Latin American Crop; 150 Years Ago, It Wiped Out An Empire". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- Carvalho CR, Fernandes RC, Carvalho GM, Barreto RW, Evans HC (2011). "Cryptosexuality and the genetic diversity paradox in coffee rust, Hemileia vastatrix". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e26387. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626387C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026387. PMC 3216932. PMID 22102860.

- "Coffee rust". Coffee rust. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Compendium of coffee diseases and pests. Gaitán, Alvaro León. St. Paul, Minnesota. 2015. ISBN 978-0-89054-472-3. OCLC 1060617649.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "PlantVillage". Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Fernando (2019-04-22). "How to Monitor For & Prevent Coffee Leaf Rust". Perfect Daily Grind. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Silva, Maria do Céu; Várzea, Victor; Guerra-Guimarães, Leonor; Azinheira, Helena Gil; Fernandez, Diana; Petitot, Anne-Sophie; Bertrand, Benoit; Lashermes, Philippe; Nicole, Michel (2006). "Coffee resistance to the main diseases: Leaf rust and coffee berry disease". Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology. 18: 119–147. doi:10.1590/s1677-04202006000100010.

- https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/fungalbasidio/pdlessons/Pages/CoffeeRust.aspx. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Bebber, Daniel P.; Castillo, Ángela Delgado; Gurr, Sarah J. (2016). "Modelling coffee leaf rust risk in Colombia with climate reanalysis data". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1709): 20150458. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0458. PMC 5095537. PMID 28080984.

- Waller, J.M.; Bigger, M.; Hillocks, R.J. (2007). Coffee Pests, Dieases & Their Management. CABI. ISBN 978-1845931292.

- Watson, Mike (10 May 2008). "Why Sri Lanka Is Everyone's Cup of Tea". Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales). Questia Online Library. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Steiman, Shawn. "Hemileia vastatrix". Coffee Research.org. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- Penarredonda, Jose Luis. "The disease that could change how we drink coffee". Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- Kollewe, Julia (2011-04-21). "Coffee prices expected to rise as a result of poor harvests and growing demand". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- "Coffee Price Increase 2011-2012 – Coffee Prices – Coffee Shortage Due to Emerging Markets". Gourmetcoffeelovers.

- "Guatemala's coffee rust 'emergency' devastates crops". BBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Guatemala declares national coffee emergency February 08, 2013 BusinessWeek

- Saliba, Frédéric (26 March 2013). "Coffee rust plagues farmers in Mexico". Retrieved 30 August 2016 – via The Guardian.

- Coffee Research Institute: Coffee rust

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Coffee rust

- The University of Hawaii page on Hemileia vastatrix

- U.S.Dept.Agriculture page on Coffee Leaf Rust

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hemileia vastatrix. |