Helianthus annuus

Helianthus annuus, the common sunflower, is a large annual forb of the genus Helianthus grown as a crop for its edible oil and edible fruits. This sunflower species is also used as wild bird food, as livestock forage (as a meal or a silage plant), in some industrial applications, and as an ornamental in domestic gardens. The plant was first domesticated in the Americas. Wild Helianthus annuus is a widely branched annual plant with many flower heads. The domestic sunflower, however, often possesses only a single large inflorescence (flower head) atop an unbranched stem. The name sunflower may derive from the flower's head's shape, which resembles the sun.

| Helianthus annuus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Horticultural variety of common sunflower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Helianthus |

| Species: | H. annuus |

| Binomial name | |

| Helianthus annuus | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

Sunflower seeds were brought to Europe from the Americas in the 16th century, where, along with sunflower oil, they became a widespread cooking ingredient.

Description

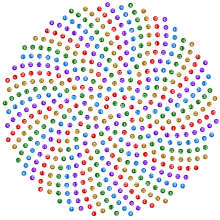

The plant has an erect rough-hairy stem, reaching typical heights of 3 metres (9.8 ft). The tallest sunflower on record achieved 9.17 metres (30.1 ft).[2] Sunflower leaves are broad, coarsely toothed, rough and mostly alternate. What is often called the "flower" of the sunflower is actually a "flower head" or pseudanthium of numerous small individual five-petaled flowers ("florets"). The outer flowers, which resemble petals, are called ray flowers. Each "petal" consists of a ligule composed of fused petals of an asymmetrical ray flower. They are sexually sterile and may be yellow, red, orange, or other colors. The flowers in the center of the head are called disk flowers. These mature into fruit (sunflower "seeds"). The disk flowers are arranged spirally. Generally, each floret is oriented toward the next by approximately the golden angle, 137.5°, producing a pattern of interconnecting spirals, where the number of left spirals and the number of right spirals are successive Fibonacci numbers. Typically, there are 34 spirals in one direction and 55 in the other; however, in a very large sunflower head there could be 89 in one direction and 144 in the other.[3][4][5] This pattern produces the most efficient packing of seeds mathematically possible within the flower head.[6][7][8]

Most cultivars of sunflower are variants of Helianthus annuus, but four other species (all perennials) are also domesticated. This includes H. tuberosus, the Jerusalem artichoke, which produces edible tubers.

Mathematical model of floret arrangement

A model for the pattern of florets in the head of a sunflower was proposed by H. Vogel in 1979.[9] This is expressed in polar coordinates

where θ is the angle, r is the radius or distance from the center, and n is the index number of the floret and c is a constant scaling factor. It is a form of Fermat's spiral. The angle 137.5° is related to the golden ratio (55/144 of a circular angle, where 55 and 144 are Fibonacci numbers) and gives a close packing of florets. This model has been used to produce computer graphics representations of sunflowers.[10]

Genome

The sunflower, Helianthus annuus, genome is diploid with a base chromosome number of 17 and an estimated genome size of 2871–3189 Mbp.[11][12] Some sources claim its true size is around 3.5 billion base pairs (slightly larger than the human genome).[13]

Cultivation and uses

To grow best, sunflowers need full sun. They grow best in fertile, moist, well-drained soil with heavy mulch. In commercial planting, seeds are planted 45 cm (1.48 ft) apart and 2.5 cm (0.98 in) deep. Sunflower "whole seed" (fruit) are sold as a snack food, raw or after roasting in ovens, with or without salt and/or seasonings added. Sunflowers can be processed into a peanut butter alternative, sunflower butter. In Germany, it is mixed with rye flour to make Sonnenblumenkernbrot (literally: sunflower whole seed bread), which is quite popular in German-speaking Europe. It is also sold as food for birds and can be used directly in cooking and salads. Native Americans had multiple uses for sunflowers in the past, such as in bread, medical ointments, dyes and body paints.[14]

Sunflower halva is popular in countries in Eastern Europe, including Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Russia, and Ukraine as well as other countries of the former Soviet Union. It is made of sunflower seeds instead of sesame.

Sunflower oil, extracted from the seeds, is used for cooking, as a carrier oil and to produce margarine and biodiesel, as it is cheaper than olive oil. A range of sunflower varieties exist with differing fatty acid compositions; some "high-oleic" types contain a higher level of monounsaturated fats in their oil than even olive oil. The oil is also sometimes used in soap.[15]

The cake remaining after the seeds have been processed for oil is used as a livestock feed.[16] The hulls resulting from the dehulling of the seeds before oil extraction can also be fed to domestic animals.[17] Some recently developed cultivars have drooping heads. These cultivars are less attractive to gardeners growing the flowers as ornamental plants, but appeal to farmers, because they reduce bird damage and losses from some plant diseases. Sunflowers also produce latex, and are the subject of experiments to improve their suitability as an alternative crop for producing hypoallergenic rubber.

Traditionally, several Native American groups planted sunflowers on the north edges of their gardens as a "fourth sister" to the better-known three sisters combination of corn, beans, and squash.[18] Annual species are often planted for their allelopathic properties.[19] It was also used by Native Americans to dress hair.[15]

However, for commercial farmers growing commodity crops other than sunflowers, the wild sunflower, like any other unwanted plant, is often considered a weed. Especially in the Midwestern US, wild (perennial) species are often found in corn and soybean fields and can decrease yields.

Sunflowers can be used in phytoremediation to extract toxic ingredients from soil, such as lead, arsenic and uranium, and used in rhizofiltration to neutralize radionuclides and other toxic ingredients and harmful bacteria from water. They were used to remove caesium-137 and strontium-90 from a nearby pond after the Chernobyl disaster,[20] and a similar campaign was mounted in response to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[21][22]

Seed dehulled (left) and with hull (right)

Seed dehulled (left) and with hull (right) Near Rietz-Neuendorf, Germany

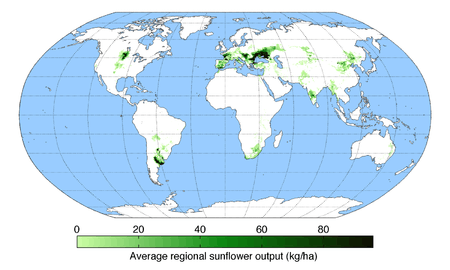

Near Rietz-Neuendorf, Germany Worldwide sunflower output

Worldwide sunflower output

Cultivars

Sunflowers are grown as ornamentals in a domestic setting. Being easy to grow and producing spectacular results in any good, moist soil in full sun, they are a favourite subject for children. A large number of cultivars, of varying size and colour, are now available to grow from seed. The following are cultivars of sunflowers (those marked agm have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit):-[23]

- American Giant

- Arnika

- Autumn Beauty

- Aztec Sun

- Black Oil

- Chianti Hybrid

- Claret agm[24]

- Dwarf Sunspot

- Evening Sun

- Florenza

- Giant Primrose

- Gullick's Variety agm[25]

- Incredible

- Indian Blanket Hybrid

- Irish Eyes

- Italian White

- Kong Hybrid

- Large Grey Stripe

- Lemon Queen agm[26]

- Loddon Gold agm[27]

- Mammoth Russian

- Miss Mellish agm[28]

- Mongolian Giant

- Orange Sun

- Pastiche agm[29]

- Peach Passion

- Peredovik

- Prado Red

- Red Sun

- Ring of Fire

- Rostov

- Skyscraper

- Solar Eclipse

- Soraya

- Strawberry Blonde

- Sunny Hybrid

- Sunshine

- Taiyo

- Tarahumara

- Teddy Bear

- Thousand Suns

- Titan

- Valentine agm[30]

- Velvet Queen

- Yellow Disk

Prado Red

Prado Red Mammoth Russian

Mammoth Russian_02.jpg) Teddy Bear

Teddy Bear

Heliotropism in Helianthus annuus

_%E2%98%86%E5%BD%A111.jpg)

A common misconception is that flowering sunflower heads track the Sun across the sky. Although immature flower buds exhibit this behaviour, the mature flowering heads point in a fixed (and typically easterly) direction throughout the day.[31][32] This old misconception was disputed in 1597 by the English botanist John Gerard, who grew sunflowers in his famous herbal garden: "[some] have reported it to turn with the Sun, the which I could never observe, although I have endeavored to find out the truth of it."[33] The uniform alignment of sunflower heads in a field might give some people the false impression that the flowers are tracking the Sun.

This alignment results from heliotropism in an earlier development stage, the young flower stage, before full maturity of flower heads (anthesis).[34] Young sunflowers orient themselves in the direction of the sun. At dawn the head of the flower faces east and moves west throughout the day. When sunflowers reach full maturity they no longer follow the sun, and continuously face east. Young flowers reorient overnight to face east in anticipation of the morning. Their heliotropic motion is a circadian rhythm, synchronized by the sun, which continues if the sun disappears on cloudy days or if plants are moved to constant light.[35] They are able to regulate their circadian rhythm in response to the blue-light emitted by a light source.[35] If a sunflower plant in the bud stage is rotated 180°, the bud will be turning away from the sun for a few days, as resynchronization by the sun takes time.[36]

When growth of the flower stalk stops and the flower is mature, the heliotropism also stops and the flower faces east from that moment onward. This eastward orientation allows rapid warming in the morning and, as a result, an increase in pollinator visits.[35] Sunflowers do not have a pulvinus below their inflorescence. A pulvinus is a flexible segment in the leaf stalks (petiole) of some plant species and functions as a 'joint'. It effectuates leaf motion due to reversible changes in turgor pressure, which occurs without growth. The sensitive plant's closing leaves are a good example of reversible leaf movement via pulvinuli.

History

This species was one of several plants cultivated by Native Americans in prehistoric North America as part of the Eastern Agricultural Complex. Although it was commonly accepted that the sunflower was first domesticated in what is now the southeastern US, roughly 5000 years ago,[37] there is evidence that it was first domesticated in Mexico[38] around 2600 BC. These crops were found in Tabasco, Mexico at the San Andres dig site. The earliest known examples in the United States of a fully domesticated sunflower have been found in Tennessee, and date to around 2300 BC.[39] Other very early examples come from rockshelter sites in Eastern Kentucky.[40] Many indigenous American peoples used the sunflower as the symbol of their solar deity, including the Aztecs and the Otomi of Mexico and the Incas in South America. In 1510 early Spanish explorers encountered the sunflower in the Americas and carried its seeds back to Europe.[41] Of the four plants known to have been domesticated in eastern North America[42] and to have become important agricultural commodities, the sunflower is currently the most economically important.

During the 18th century, the use of sunflower oil became very popular in Russia, particularly with members of the Russian Orthodox Church, because sunflower oil was one of the few oils that was allowed during Lent, according to some fasting traditions.[43] In the early 19th century it was first commercialized in the village of Alexeyevka in Voronezh Governorate by the merchant named Daniil Bokaryov, who developed a technology suitable for its large-scale extraction, and quickly spread around. The town's coat of arms includes an image of a sunflower ever since.

During the 19th century, it was believed that nearby plants of the species would protect a home from malaria.[15]

Among the Zuni people, the fresh or dried root is chewed by the medicine man before sucking venom from a snakebite and applying a poultice to the wound.[44] This compound poultice of the root is applied with much ceremony to rattlesnake bites.[45] Blossoms are also used ceremonially for anthropic worship.[46]

Culture

- The sunflower is the state flower of the US state of Kansas, and one of the city flowers of Kitakyūshū, Japan.

- The sunflower is often used as a symbol of green ideology. The sunflower is also the symbol of the Vegan Society.

- During the late 19th century, the flower was used as the symbol of the Aesthetic Movement.

- The flowers were the subject of Van Gogh's Sunflowers series of paintings.

- The sunflower is the national flower of Ukraine.

- The sunflower was chosen as the symbol of the Spiritualist Church for many reasons, but mostly because it turns toward the sun as "Spiritualism turns toward the light of truth". As stated earlier in the article, this is in fact, not true. Modern Spiritualists often have art or jewelry with sunflower designs.[47]

- Sunflowers were also worshipped by the Incas because they viewed it as a symbol for the Sun.[48]

- The sunflower is the symbol behind the Sunflower Movement, a 2014 mass protest in Taiwan.

Other species

There are many species in the sunflower genus Helianthus, and many species in other genera that may be called sunflowers.

- The Maximillian sunflower (Helianthus maximiliani) is one of 38 species of perennial sunflower native to North America. The Land Institute and other breeding programs are currently exploring the potential for these as a perennial seed crop.

- The sunchoke (Jerusalem artichoke or Helianthus tuberosus) is related to the sunflower, another example of perennial sunflower.

- The Mexican sunflower is Tithonia rotundifolia. It is only very distantly related to North American sunflowers.

- False sunflower refers to plants of the genus Heliopsis.

Sunflower hybrids

In today's market, most of the sunflower seeds provided or grown by farmers are hybrids. Hybrids or hybridized sunflowers are produced by crossbreeding different types and species of sunflower, for example crossbreeding cultivated sunflowers with wild species of sunflowers. By doing so, new genetic recombinations are obtained ultimately leading to the production of new hybrid species. These hybrid species generally have a higher fitness and carry properties or characteristics that farmers look for, such as resistance to pathogens.[49]

Hybrid, Helianthus annuus dwarf2 does not contain the hormone gibberellin and does not display heliotropic behavior. Plants treated with an external application of the hormone display a temporary restoration of elongation growth patterns. This growth pattern diminished by 35% 7–14 days after final treatment.[35]

Hybrid male sterile and male fertile flowers that display heterogeneity have a low crossover of honeybee visitation. Sensory cues such as pollen odor, diameter of seed head, and height may influence pollinator visitation of pollinators that display constancy behavior patterns.[50]

Threats and diseases

One of the major threats that sunflowers face today is Fusarium, a filamentous fungus that is found largely in soil and plants. It is a pathogen that over the years has caused an increasing amount of damage and loss of sunflower crops, some as extensive as 80 percent of damaged crops.[49]

Downy mildew is another disease to which sunflowers are susceptible. Its susceptibility to downy mildew is particular high due to the sunflower's way of growth and development. Sunflower seeds are generally planted only an inch deep in the ground. When such shallow planting is done in moist and soaked earth or soil, it increases the chances of diseases such as downy mildew.

Another major threat to sunflower crops is broomrape, a parasite that attacks the root of the sunflower and causes extensive damage to sunflower crops, as high as 100 percent.[51]

See also

- List of sunflower diseases

- International Sunflower Guerrilla Gardening Day

References

- Footnotes

- "Helianthus annuus". The Global Compositae Checklist (GCC) – via The Plant List.

- "Tallest Sunflower". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Adam, John A. (2003). John A. Adam, Mathematics in Nature. ISBN 978-0-691-11429-3. Retrieved 2011-01-31 – via Google Books.

- "R. Knott, Interactive demos". Mcs.surrey.ac.uk. 2009-02-12. Archived from the original on 2009-09-16. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- "R. Knott, Fibonacci in plants". Mcs.surrey.ac.uk. 2010-10-30. Archived from the original on 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- Motloch, John L (2000-08-25). Introduction to landscape design - Google Books. ISBN 978-0-471-35291-4. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- Jean, Roger V (1994). Phyllotaxis. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-521-40482-2. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

fibonacci packing efficiency.

- "Parastichy pair(13:21) of CYCAS REVOLUTA (male) florets_WebCite". Archived from the original on October 3, 2009.

- Vogel, H (1979). "A better way to construct the sunflower head". Mathematical Biosciences. 44 (3–4): 179–189. doi:10.1016/0025-5564(79)90080-4.

- Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw; Lindenmayer, Aristid (1990). The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Springer-Verlag. pp. 101–107. ISBN 978-0-387-97297-8.

- "Helianthus annuus (common sunflower) Genome Project". NCBI. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- "Helianthus annuus". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "Sunflower Genome Holds the Promise of Sustainable Agriculture". ScienceDaily. 2010-01-14.

- Pelczar, Rita. (1993) The Prodigal Sunflower. American Horticulturist 72(8).

- Niering, William A.; Olmstead, Nancy C. (1985) [1979]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. Knopf. p. 384. ISBN 0-394-50432-1.

- Heuzé V., Tran G., Hassoun P., Lessire M., Lebas F., 2016. Sunflower meal. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/732

- Heuzé V., Tran G., Hassoun P., Lessire M., Lebas F., 2018. Sunflower hulls and sunflower screenings. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/733

- Kuepper and Dodson (2001) Companion Planting: Basic Concept and Resources Archived 2008-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Nikneshan, P., Karimmojeni, P., Moghanibashi, M., Hosseini, N. (2011) Australian Journal of Crop Science. 5(11):1434-40. ISSN 1835-2707. Allelopathic potential of sunflower on weed management in safflower and wheat

- Adler, Tina (July 20, 1996). "Botanical cleanup crews: using plants to tackle polluted water and soil". Science News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- AFP (June 24, 2011). "Sunflowers to clean radioactive soil in Japan". Yahoo News. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- Antoni Slodkowski; Yuriko Nakao (19 August 2011). "Sunflowers melt Fukushima's nuclear "snow"". Reuters. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 43. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus annuus 'Claret' / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus 'Gullick's Variety' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus 'Lemon Queen' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus 'Loddon Gold' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus 'Miss Mellish' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus annuus 'Pastiche' / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "RHS Plant Selector Helianthus annuus 'Valentine' / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- "Many people are under the misconception that the flower heads of the cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus) track the sun... Immature sunflower flower heads do exhibit solar tracking and on sunny days the buds will track the sun across the sky from east to west... However, as the flower bud matures and blossoms, the stem stiffens and the flower head becomes fixed facing the eastward direction." Hangarter, Roger P. "Solar tracking: sunflower plants". Plants-In-Motion website. Indiana University. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Sunflowers in the blooming stage are not heliotropic anymore. The stem has frozen, typically in an eastward orientation". Archived from the original on 2013-05-23.

- Gerard, John (1597). Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes. London: John Norton. pp. 612–614. Retrieved 2012-08-08. Popular botany book in 17th century England

- "Sunflower, Developmental stages (life cycle)". GeoChemBio website. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Atamian, Hagop S.; Creux, Nicky M.; Brown, Evan A.; Garner, Austin G.; Blackman, Benjamin K.; Harmer, Stacey L. (2016-08-05). "Circadian regulation of sunflower heliotropism, floral orientation, and pollinator visits". Science. 353 (6299): 587–590. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..587A. doi:10.1126/science.aaf9793. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27493185.

- Donat-Peter Häder; Michael Lebert (2001). Photomovement. Elsevier. pp. 673–. ISBN 978-0-444-50706-8. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Blackman et al. (2011). . PNAS.

- Lentz et al. (2008). PNAS.

- Rieseberg, Loren H., et al. (2004). Origin of Extant Domesticated Sunflowers in Eastern North America. Nature 430.6996. 201-205.

- Henderson & Pollack (2012). .

- Putt, E.D. (1997). "Early history of sunflower". In A.A. Schneiter (ed.). Sunflower Technology and Production. Agronomy Series. 35. Madison, Wisconsin: American Society of Agronomy. pp. 1–19.

- Smith (2006). . PNAS.

- SUNFLOWERS: The Secret History. (2007). Kirkus Reviews 75.23:1236. Academic Search Complete. Web. 17 November 2012.

- Camazine, Scott and Robert A. Bye (1980) A Study Of The Medical Ethnobotany Of The Zuni Indians of New Mexico. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2:365-388 (p.375)

- Stevenson, Matilda Coxe (1915) Ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians. SI-BAE Annual Report #30 (p.53-54)

- Stevenson, p.93

- Awtry-Smith, Marilyn J. The Symbol of Spiritualism: The Sunflower. Reprinted from the New Educational Course on Modern Spiritualism. Appendix IV in Talking to the Other Side: A History of Modern Spiritualism and Mediumship, ed. by Todd Jay Leonard. ISBN 0-595-36353-9.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-18. Retrieved 2014-03-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gontcharov, SV. Antonova, TS. and Saukova, SL. 2006. Sunflower breeding for resistance to fusarium. Helia [accessed September 14, 2014]; 29 (45): 49-54.

- Martin, Cinthia Susic; Farina, Walter M. (2016-03-01). "Honeybee floral constancy and pollination efficiency in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) crops for hybrid seed production". Apidologie. 47 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1007/s13592-015-0384-8. ISSN 0044-8435.

- Encheva, J. Christov, M and Shindrova, P. Developing Mutant Sunflower Line (Helianthus Annuus L.) By Combined Used Of Classical Method With Induced Mutagenesis and Embryo Culture Method. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science [accessed October 15, 2014]; 14(4):397-404

- General

- Pope, Kevin; Pohl, Mary E. D.; Jones, John G.; Lentz, David L.; von Nagy, Christopher; Vega, Francisco J.; Quitmyer Irvy R. (18 May 2001). "Origin and Environmental Setting of Ancient Agriculture in the Lowlands of Mesoamerica". Science, 292(5520):1370–1373.

- Shosteck, Robert (1974) Flowers and Plants: An International Lexicon with Biographical Notes. New York: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co. ISBN 9780812904536.

- Wood, Marcia. (June 2002). "Sunflower Rubber? Agricultural Research". USDA. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sunflowers. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sunflowers |

| Look up sheller in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- National Sunflower Association

- Sunflowerseed—USDA Economic Research Service. Summary of sunflower production, trade, and consumption and links to relevant USDA reports.

- Sunflower cultivation—New Crop Resource Online Program, Purdue University

- Helianthus annuus —Home garden cultural information on growing sunflowers

- Sunflower seed vigor—Relationship between seed size and NaCl on germination, seed vigor and early seedling growth of sunflower (Helianthus annuus)