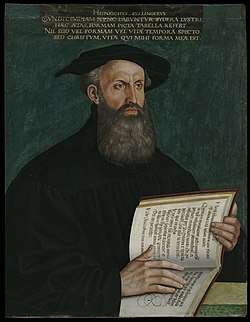

Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss reformer, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Zürich church and pastor at Grossmünster. One of the most important reformers in the Swiss reformation, Bullinger is known for authoring the Helvetic Confessions with Peter Vermingli and his work with John Calvin on the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Heinrich Bullinger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 July 1504 Bremgarten (Aargau), Canton of Aargau in the Old Swiss Confederacy |

| Died | 17 September 1575 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation | Theologian, Antistes |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Adlischwyler |

| Parent(s) | Heinrich Bullinger & Anna Wiederkehr |

Bullinger's importance in the Reformation has long been underestimated; recent research shows that he was one of the most influential theologians of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century.[1]

Life

Early life (1504–1515)

Heinrich Bullinger was born to Heinrich Bullinger Sr., a priest, and Anna Wiederkehr, at Bremgarten, Aargau, Switzerland.[2] The bishop of Constance, who had clerical oversight over Aargau, had unofficially sanctioned clerical concubinage, having waived all penalties against the offense in exchange for an annual fee called a cradle tax.[3]:18 As such, Heinrich and Anna were able to live as virtual husband and wife, and Heinrich was the fifth son born to the couple.

Studies (1516–1522)

At 12 years of age, Bullinger was sent a Latin school of Emmerich in the Duchy of Cleves where he was influenced by the Brethren of the Common Life and their Devotio moderna traditions.[4][3]:18

In 1519, at the age of 14, his parents sent him to the University of Cologne, intending him to follow his father into the clergy.[4] Although he didn't study theology at the university, two of his teachers, Johannes Pfrissemius and Arnold von Wesel, were followers of the new humanist education trend. In addition, he was in university during Martin Luther's Ninety-five Theses and the subsequent Diet of Worms controversies. Thus, during this time Bullinger was exposed works by the Latin and Greek church fathers, Thomas Aquinas and the medieval scholastics, Erasmus' humanism, and Luther.[3]:18 Bullinger later wrote in his diary that it was reading Erasmus, Luther, and Melanchthon that led him to his embrace of Lutheranism.[5][3]:18 In 1522, now a convinced follower of Martin Luther, Bullinger ceased receiving the Eucharist and gave up his previous intention of entering the Carthusian order and earned his Master of Art degree. Because of his Lutheran beliefs and actions, he was banned from obtaining a clerical position in the Roman Catholic Church.[6]

Kappel Abbey and the early Swiss Reformation (1523–1531)

In 1523, he accepted a post as a teacher at the Cisterian monastery, Kappel Abbey, though only under the conditions that he wouldn't take monastic vows or attend mass. At the school, Bullinger initiated a systematic program of Bible reading and exegesis for the monks.[2] He also endeavored to reform the monastery's Trivium curriculum in a more humanist and Protestant direction.[4][3]:18

During this time, he heard Huldrych Zwingli and Leo Jud preach several times during the Reformation in Zürich.[4] Under the influence of the Waldensians and Zwingli, Bullinger moved to a more symbolic understanding of the Eucharist. In 1527, he spent five months in Zürich studying ancient languages and regularly attending the Prophezei that Zwingli had set up there. While at Zürich, the local authorities sent him with their delegation to assist Zwingli at the Bern Disputation where he met Martin Bucer, Ambrosius Blaurer, and Berthold Haller. In 1528, at the urging of the Zürich Synod, he left Kappel Abbey and became ordained as a parish minister in the then new Reformed church of Zürich.[3]:18

In 1529, Bullinger's father renounced Roman Catholicism in favour of Protestant doctrines. Consequently, his congregation at Bremgarten removed him as their priest. Several candidates were invited to preach sermons as potential replacements, including Bullinger. His sermon caused a rise in iconoclasm in the church, and the congregation stripped the images from their church and burned them. Bullinger succeeded his father and became the pastor of the church in Bremgarten.[2] In this same year, he married Anna Adlischweiler, a former nun.[2] They eventually had six sons and five daughters.[7] All of his sons became Protestant ministers.

Start of ministry at Zürich (1531)

After the defeat at Second War of Kappel (11 October 1531), where Zwingli died, the Aargau region, including Bremgarten, was forced to return to Catholicism.[4] Bullinger and two other ministers were expelled from Bremgarten, and Bullinger fled to Zürich.[2] Having gained a reputation as a leading Protestant preacher, Bullinger quickly received offers to take up the position of pastor from Zürich, Basel, Bern, and Appenzell.[2] Bullinger, out of loyalty to Zürich, wanted to stay and succeed Zwingli as head of the Zürich church. However, the Zürich government and populace were concerned over the aftermath of the Second War of Kappel, and did not want an independent clergy that could proclaim political agendas, like Zwingli's war against the Catholics in 1531.[4] Bullinger insisted that he should have a right to preach the Bible, even if it contradicted the position of the civic authorities. In a compromise, they gave Bullinger the right to run the churches in Zürich under the condition that he made sure that the clergy were not preaching politically.[4]

Bullinger took up the position of minister in 1531, and on the first Sunday after his arrival he stood in the pulpit of Grossmünster. According to a well-known quote by a contemporary at the time, Bullinger "thundered a sermon from the pulpit that many thought Zwingli was not dead but resurrected like the phoenix".[5] In December of the same year, he was, at the age of 27, elected to be the successor of Zwingli as antistes of the Zürich church. He accepted the election only after the council had assured him explicitly that he was in his preaching "free, unbound and without restriction" even if it necessitated critique of the government. He kept this office up to his death in 1575.[7]

Rebuilding the Zürich church, the First Helvetic Confession, and the Consensus Tigurinus (1531–1549)

In the aftermath of the Second War of Kappel and Zwingli's death, Bullinger's largest task was to quickly rebuild the Zürich church.[3]:19

Bullinger quickly established himself as a staunch defender of the ecclesiological system developed by Zwingli. In 1532, when Leo Jud proposed making ecclesiastical discipline entirely separate from the secular power, Bullinger argued that separation of church and state courts was only needed if the government is not Christian. Also in 1532, he was instrumental in creating a joint committee of magistrates and ministers to oversee the church.

In light of Protestant disunity, Bullinger, together with Basel reformers Oswald Myconius and Simon Grynaeus, drafted the First Helvetic Confession in 1536 to unify the beliefs of the Reformed churches in Switzerland. The confession was eventually adopted by most European Protestant churches, and set the standard for later confessions of faiths. The confession of faith was a combination of Zwinglian and Lutheran theology.[7]

Although the goal of the First Helvetic Confession was eventually to unite the Swiss churches with the Lutheran churches in the Wittenberg Concord, Bullinger distrusted Martin Bucer, and by 1538 negotiations broke down.[3]:19 The break between the Swiss Reformed churches and the Lutheran never healed, during the last years of Luther's life, Luther continued to denounce the Swiss Zwinglians in Luther's 1543 Short Confession of the Lord's Supper. Bullinger responded to this with his own True Confession in 1545.[3]:20

During this time he also was addressing and debating the Anabaptists, especially with his 1531 work, Four Books to Warn the Faithful of the Shameless Disturbance, Offensive Confusion, and False Teachings of the Anabaptists. By the 1540s, Bullinger could find no agreement with the Roman Catholics, Lutherans, or Anabaptists, which drew him and reformer John Calvin of Geneva into closer contact. Together they penned a response to the Council of Trent. Then, in 1549, they drafted the Consensus Tigurinus together, which is viewed as a significant point of agreement on the doctrine of the Eucharist between the Calvinists and the Zwinglians.[7][3]:20

During this time, Bullinger opened Zürich to Protestant fugitives. In the late 1540s, Anne Hooper, then a Protestant fugitive from England, became Bullinger's correspondent. In 1546, Bullinger was the godfather of Hooper's daughter during her infant baptism.[8]

Later years (1550–1575)

He worked closely with Thomas Erastus to promote the Reformed orientation of the Reformation of the Electorate of the Palatinate in the 1560s.

Bullinger played a crucial role in the drafting of the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. What eventually became the Second Helvetic Confession originated in a personal statement of his faith which Bullinger intended to be presented to the Zürich Rathaus upon his death. In 1566, when the Frederick III the Pious, elector palatine introduced Reformed elements into the church in his region, Bullinger felt that this statement might be useful for the elector, so he had it circulated among the Protestant cities of Switzerland who signed to indicate their assent. Later, the Reformed churches of France, Scotland, and Hungary would do likewise.

He died at Zürich and was followed as antistes by Zwingli's son-in-law Rudolf Gwalther. His circle of collaborators in the Zürich church and Carolinum academy included Gwalther, Konrad Pellikan, Theodor Bibliander, Peter Martyr Vermigli, Johannes Wolf, Josias Simler, and Ludwig Lavater.

Among his descendants was the noted Biblical scholar E.W. Bullinger.

See Carl Pestalozzi, Leben (1858); Raget Christoffel, H. Bullinger (1875); Justus Heer, in Hauck's Realencyklopädie (1897).

Impact on England

Bullinger accepted many Protestant fugitives from England after the passing of the Six Articles in 1539 by Henry VIII and again during the rule of Mary I of England from 1553–1558. When the English fugitives returned to England after the death of Mary I, Bullinger's writings found a broad distribution in England. In England, from 1550–1560, there were 77 editions of Bullinger's Latin Decades and 137 editions of their vernacular translation House Book, a treatise in pastoral theology. In comparison, Calvin's Institutes had two editions in England during the same time.[8] In an 1586 order of the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgrift ordered all non-graduate ordinands to buy and read Bullinger's Decades.[5]

Second Helvetic Confession

The Second Helvetic Confession (Latin: Confessio Helvetica posterior, or CHP) was mainly written by Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575), pastor and the successor of Huldrych Zwingli in Zürich, Switzerland. The Second Helvetic Confession was written in 1561 as a private exercise. It came to the notice of the elector palatine Frederick III, who had it translated into German and published in 1566. It gained a favourable hold on the Swiss churches in Bern, Zürich Schaffhausen St. Gallen, Chur, Geneva and other cities. The Second Helvetic Confession was adopted by the Reformed Church not only throughout Switzerland but in Scotland (1566), Hungary (1567), France (1571), Poland (1578), and next to the Heidelberg Catechism is the most generally recognized Confession of the Reformed Church. Slight variations of this confession existed in the French Confession de Foy (1559), the Scottish Confessio Fidei (1560) the Belfian Ecclasiarum Belgicarum Confessio (1561) and the Heidelberg Catechism (1563).

Marian views

Mary is mentioned several times in the Second Helvetic Confession, which expounds Bullinger's mariology. Chapter Three quotes the angel’s message to the Virgin Mary, " – the Holy Spirit will come over you " - as an indication of the existence of the Holy Spirit and the Trinity. The Latin text described Mary as diva, indicating her rank as a person, who dedicated herself to God. In Chapter Nine, the Virgin birth of Jesus is said to be conceived by the Holy Spirit and born without the participation of any man. The Second Helvetic Confession accepted the "Ever Virgin" notion from John Calvin, which spread throughout much of Europe with the approbation of this document in the above-mentioned countries.[9] Bullinger's 1539 polemical treatise against idolatry[10] expressed his belief that Mary's "sacrosanctum corpus" ("sacrosanct body") had been assumed into heaven by angels:

Hac causa credimus et Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum.[11]

For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels.[12]

The French Confession de Foy, the Scottish Confessio Fidei, the Belgian Ecclasiarum Belgicarum Confessio and the Heidelberg Catechism, all include references to the Virgin Birth, mentioning specifically, that Jesus was born without the participation of a man.[9] Invocations to Mary were not tolerated, however, in light of Calvin’s position that any prayer to saints in front of an altar is prohibited.

Works

Bullinger's works comprise 127 titles, in addition to 12,000 surviving letters. In total, his total amount of writings exceed Luther and Calvin combined.[5] During his lifetime they were translated in several languages and counted among the best known theological works in Europe.

Theological works

His main work were the Decades, a treatise in pastoral theology, in the vernacular called "House Book".

The (second) Helvetic Confession (1566) adopted in Switzerland, Hungary, Bohemia and elsewhere, was originally believed to be only his work. However, this has been recently challenged, in that Peter Martyr Vermigli played a decisive role in this document as well. The volumes of the Zürich Letters, published by the Parker Society, testify to his influence on the English reformation in later stages.

Many of his sermons were translated into English (reprinted, 4 vols., 1849). His works, mainly expository and polemical, have not been collected.

- Second decade, eighth sermon, The Magistrate

- Second decade, ninth sermon, "Of War; Whether it be Lawful for a Magistrate to Make War. What the Scripture Teacheth Touching War. Whether a Christian Man May Bear the Office of a Magistrate. And of the Duty of Subjects." (Emphasis added.)

- Fourth decade, fourth sermon, Predestination

- An Answer Given To A Certain Scotsman, In Reply To Some Questions Concerning The Kingdom Of Scotland And England

- Microfiche collection of his original works

- Werke - Institut für schweizerische Reformationsgeschichte, Universität Zürich

Historical

Besides theological works, Bullinger also wrote some historical works of value. The main of it, the "Tiguriner Chronik" is a history of Zürich from Roman times to the Reformation, others are a history of the Reformation and a history of the Swiss confederation. Bullinger also wrote in detail on Biblical chronology, working within the framework that was universal in the Christian theological tradition until the second half of the 17th century, namely that the Bible affords a faithful and normative reference for all ancient history.[13]

Letters

There exist about 12,000 letters from and to Bullinger, the most extended correspondence preserved from Reformation times. He mainly wrote in Latin with some quotes in Hebrew and Greek, with about 10 percent in Early New High German.

Bullinger was a personal friend and advisor of many leading personalities of the reformation era. He corresponded with Reformed, Anglican, Lutheran, and Baptist theologians, with Henry VIII of England, Edward VI of England, Lady Jane Grey and Elizabeth I of England, Christian II of Denmark, Philipp I of Hesse and Frederick III, Elector Palatine.

Legacy

Bullinger's Helvetic Confessions are still used by Reformed churches as a theological standard. His legacy as a writer and historian survives today. His idea of covenant influenced the development of covenant theology in America.[5]

Due to his involvement and correspondence with the English Reformers, some historians count Bullinger together with Bucer as the most influential theologian of the Anglican reformation.

Bullinger also accepted fugitives from northern Italy and France, especially after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre.[7] Johann Pestalozzi was a descendant of the Italian fugitives.[8]

References

- Kirby, Torrance (2005). "Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575): Life - Thought - Influence". Zwingliana. 32. ISSN 0254-4407.

- "Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575)". Musée protestant. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Gordon, Bruce (2004). Gordon, Bruce; Campi, Emidio (eds.). Architect of Reformation: An Introduction to Heinrich Bullinger, 1504-1575. Texts and Studies in Reformation and Post-Reformation Thought. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801028991.

- Bruce, Gordon (2003). Bullinger, Heinrich (1504–1575). Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World. Charles Scribner & Sons. ISBN 9780684312002.

- Ives, Eric (2012). The Reformation Experience: Living Through The Turbulent 16th Century. Lion Books. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9780745952772.

- "Heinrich Bullinger | Swiss religious reformer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Shane, E. D. (2002). Bullinger, Heinrich. New Catholic Encyclopedia. Gale Research Inc. ISBN 9780787640040.

- Ben Lowe (2 March 2017). Commonwealth and the English Reformation: Protestantism and the Politics of Religious Change in the Gloucester Vale, 1483–1560. Routledge. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-1-351-95038-1.

- Chavannes 426

- De origine erroris libri duo (On the Origin of Error, Two Books) . "In the De origine erroris in divorum ac simulachrorum cultu he opposed the worship of the saints and iconolatry; in the De origine erroris in negocio Eucharistiae ac Missae he strove to show that the Catholic conceptions of the Eucharist and of celebrating the Mass were wrong. Bullinger published a combined edition of these works in 4 ° (Zürich 1539), which was divided into two books, according to themes of the original work." The Library of the Finnish nobleman, royal secretary and trustee Henrik Matsson (ca. 1540–1617), Terhi Kiiskinen Helsinki: Academia Scientarium Fennica (Finnish Academy of Science), 2003, ISBN 951-41-0944-9 ISBN 9789514109447, p. 175

- De origine erroris, Caput XVI (Chapter 16), p. 70 (thumbnail 146)

- The Thousand Faces of the Virgin Mary (1996), George H. Tavard, Liturgical Press ISBN 0-8146-5914-4 ISBN 9780814659144, p. 109.

- Refer to Jean-Marc Berthoud's paper for a fuller discussion. In this respect, Berthoud compares Bullinger to James Ussher and Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heinrich Bullinger. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bullinger, Heinrich. |

- Works by Heinrich Bullinger at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Works by Heinrich Bullinger at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Heinrich Bullinger at Internet Archive

- Heinrich Bullinger, Reformationsgeschichte, on-line

- Burnett, Amy Nelson and Campi, Emidio (eds). A Companion to the Swiss Reformation, Leiden - Boston: Brill, 2016. ISBN 978-90-04-30102-3

- Bruce Gordon and Emidio Campi (eds) Architect of Reformation. An Introduction to Heinrich Bullinger (Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI, 2004) 978-0801028991

- Carl Pestalozzi: Heinrich Bullinger: Leben und ausgewählte Schriften, 1858 on-line

- The Successor, Magazine Reformierte Presse 2004

- Heinrich Bullinger and the Reformation. A comprehensive faith by Jean-Marc Berthoud

- The Civil Magistrate and the cura religionis: Heinrich Bullinger’s Prophetical Office and the English Reformation

- Heinrich Bullinger 1504-75: Man of Reconciliation

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Huldrych Zwingli |

Antistes of Zürich 1532–1575 |

Succeeded by Rudolph Gualther |