Health at Every Size

Health at Every Size (HAES) is a hypothesis advanced by certain sectors of the fat acceptance movement. It is promoted by the Association for Size Diversity and Health, a tax-exempt nonprofit organization that owns the phrase as a registered trademark.[1][2][3] Proponents reject the scientific consensus regarding the health effects greater body weight,[4][5] and argue that traditional interventions focused on weight loss, such as dieting, do not reliably produce positive health outcomes.[6] The benefits of lifestyle interventions such as nutritious eating and exercise are presumed to be real, but independent of any weight loss they may cause. At the same time, HAES advocates espouse that sustained, large-scale weight loss is difficult to the point of effective impossibility for the majority of people, including those who are obese. HAES proponents believe that health is a result of behaviors that are independent of body weight and that favoring being thin discriminates against the overweight and the obese.[7] Efforts towards such weight loss are instead held to cause rapid swings in size that inflict far worse physical and psychological damage than would obesity itself.[8]

History

Health at Every Size first appeared in the 1960s, advocating that the changing culture toward aesthetics and beauty standards had negative health and psychological repercussions to fat people. They believed that because the slim and fit body type had become the acceptable standard of attractiveness, fat people were going to great pains to lose weight, and that this was not, in fact, always healthy for the individual. They contend that some people are naturally a larger body type, and that in some cases losing a large amount of weight could in fact be extremely unhealthy for some. On November 4, 1967, Lew Louderback wrote an article called "More People Should Be Fat!" that appeared in a major national magazine, The Saturday Evening Post.[9] In the opinion piece, Louderback argued that:

- "Thin fat people" suffer physically and emotionally from having dieted to below their natural body weight.

- Forced changes in weight are not only likely to be temporary, but also to cause physical and emotional damage.

- Dieting seems to unleash destructive and emotional tendencies.

- Eating without dieting allowed Louderback and his wife to relax and feel better while maintaining the same weight.

Bill Fabrey, a young engineer at the time, read the article and contacted Louderback a few months later in 1968. Fabrey helped Louderback research his subsequent book, Fat Power, and Louderback supported Fabrey in founding the National Association to Aid Fat Americans (NAAFA) in 1969, a nonprofit human rights organization. NAAFA would subsequently change its name by the mid-1980s to the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance.

In the early 1980s, four books collectively put forward ideas related to Health At Every Size. In Diets Don't Work (1982), Bob Schwartz encouraged "intuitive eating",[10] as did Molly Groger in Eating Awareness Training (1986). Those authors believed this would result in weight loss as a side effect. William Bennett and Joel Gurin's The Dieter's Dilemma (1982), and Janet Polivy and C. Peter Herman's Breaking The Diet Habit (1983) argued that everybody has a natural weight and set-point, and that dieting for weight loss does not work.[11]

Science

Proponents claim that evidence from certain scientific studies has provided some rationale for a shift in focus in health management from weight loss to a weight-neutral approach in individuals who have a high risk of type 2 diabetes and/or symptoms of cardiovascular disease, and that a weight-inclusive approach focusing on health biomarkers, instead of weight-normative approaches focusing on weight loss alone, provides greater health improvements.[12][13]

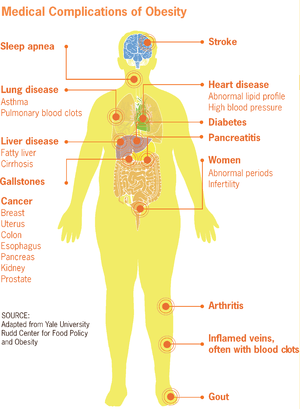

There is a considerable amount of evidence that being overweight is associated with increased all-causes mortality, and significant weight loss (>10%), using a variety of diets, improves or reverses metabolic syndromes and other health outcomes associated with overweight and obesity.[14][15][16][17] Obesity has been correlated with a wide variety of health problems.[15][4] These problems range from congestive heart failure,[18] high blood pressure,[19] deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism,[20] type 2 diabetes,[21] infertility,[22] birth defects,[23] stroke,[24] dementia,[25] cancer,[26] asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[27] and erectile dysfunction.[28] A BMI greater than 30 is associated with twice the average risk of congestive heart failure.[29][30] Obesity is associated with cardiovascular diseases including angina and myocardial infarction.[31][32] A 2002 report concluded that 21% of ischemic heart disease is due to obesity,[33] while a 2008 European consensus puts the number at 35%.[34] Obesity has been cited as a contributing factor to approximately 100,000–400,000 deaths in the United States per year[35] (including increased morbidity in car accidents).[36]

In a study with a middle-aged to elderly sample, personal recollection of maximum weight in their lifetime was recorded and an association with mortality was seen with 15% weight loss for the overweight. Moderate weight loss was associated with reduced cardiovascular risk amongst obese men. Intentional weight loss was not directly measured, but it was assumed that those that died within 3 years, due to disease etc., had not intended to lose weight.[37]

There is no evidence to support the view that some obese people eat little yet gain weight due to a slow metabolism; on average, obese people have a greater energy expenditure than their healthy-weight counterparts due to the energy required to maintain an increased body mass.[38][39][40]

Obesity, overweight and specific nutrient excess are recognized as diseases by the World Health Organization,[41] and preventable causes of death worldwide.[42]

Criticism

Amanda Sainsbury-Salis, an Australian medical researcher, calls for a rethink of the HAES concept,[43] arguing it is not possible to be and remain truly healthy at every size, and suggests that a HAES focus may encourage people to ignore increasing weight, which her research states is easiest to lose soon after gaining. She does, however, note that it is possible to have healthy behaviours that provide health benefits at a wide variety of body sizes.

David L. Katz, a prominent public health professor at Yale, wrote an article in the Huffington Post entitled "Why I Can't Quite Be Okay With 'Okay at Any Size'".[44] He does not explicitly name HAES as its topic, but discusses similar concepts. While he applauds the confrontation and combating of anti-obesity bias, his opinion is that a continued focus on being 'okay at any size' may normalize ill-health and prevent people from taking steps to reduce obesity.

In May 2017, scientists at the European Congress on Obesity expressed scepticism about the possibility of being "fat but fit".[45] A twenty-year observational study of 3.5 million participants showed that "fat but fit" people are still at higher risk of a number of diseases and adverse health effects than the general population.[46]

References

- ""Health at Every Size®" is now a Registered Trademark". Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "Trademark Guidelines". Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH). Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "Association for Size Diversity and Health Archived 2018-05-30 at the Wayback Machine". Tax Exempt Organization Search. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "www.who.int" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Ed Cara (April 22, 2016). "Health at Every Size Movement: What Proponents Say vs. What Science Says". Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

HAES has directly attacked commonly held ideas about obesity and weight...

- Mann, Traci; Tomiyama, Janet A.; Westling, Erika; Lew, Ann-Marie; Samuels, Barbra; Chatman, Jason (April 2007). "Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer". American Psychologist. Eating Disorders. 62 (3): 220–233. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.666.7484. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.62.3.220. PMID 17469900.

- Brown, Lora Beth (March–April 2009). "Teaching the 'Health at Every Size' Paradigm Benefits Future Fitness and Health Professionals". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 41 (2): 144–145. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2008.04.358. PMID 19304261.

- "Does sustained weight loss lead to decreased morbidity and mortality?". International Journal of Obesity. 23 (S5): s20–s21. 1993. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0800982.

- Louderback, Lew (November 4, 1967). "More People Should Be Fat". The Saturday Evening Post.

- Bob Schwartz (1996). Diets don't work. Breakthru Pub. ISBN 978-0-942540-16-1. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- Bruno, Barbara Altman (April 30, 2013) [2009]. "the HAES® files: History of the Health At Every Size® Movement—the 1970s & 80s (Part 2)". Health at Every Size Blog. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Tylka, TL; Annunziato, RA; Burgard, D; Daníelsdóttir, S; Shuman, E; Davis, C; Calogero, RM (2014). "The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss". Journal of Obesity. 2014: 983495. doi:10.1155/2014/983495. PMC 4132299. PMID 25147734.

- Bacon L, Aphramor L (2011). "Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift". Nutr J. 10: 9. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-10-9. PMC 3041737. PMID 21261939.

- Jensen, MD; Ryan, DH; Apovian, CM; Ard, JD; Comuzzie, AG; Donato, KA; Hu, FB; Hubbard, VS; Jakicic, JM; Kushner, RF; Loria, CM; Millen, BE; Nonas, CA; Pi-Sunyer, FX; Stevens, J; Stevens, VJ; Wadden, TA; Wolfe, BM; Yanovski, SZ; Jordan, HS; Kendall, KA; Lux, LJ; Mentor-Marcel, R; Morgan, LC; Trisolini, MG; Wnek, J; Anderson, JL; Halperin, JL; Albert, NM; Bozkurt, B; Brindis, RG; Curtis, LH; DeMets, D; Hochman, JS; Kovacs, RJ; Ohman, EM; Pressler, SJ; Sellke, FW; Shen, WK; Smith SC, Jr; Tomaselli, GF; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, Guidelines.; Obesity, Society. (June 24, 2014). "2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society". Circulation (Professional society guideline). 129 (25 Suppl 2): S102-38. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. PMC 5819889. PMID 24222017.

- Thom, G; Lean, M (May 2017). "Is There an Optimal Diet for Weight Management and Metabolic Health?" (PDF). Gastroenterology (Review). 152 (7): 1739–1751. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.056. PMID 28214525.

- Kuchkuntla, AR; Limketkai, B; Nanda, S; Hurt, RT; Mundi, MS (December 2018). "Fad Diets: Hype or Hope?". Current Nutrition Reports (Review). 7 (4): 310–323. doi:10.1007/s13668-018-0242-1. PMID 30168044.

- "Obesity and overweight". who.int. 2018.

- Kenchaiah, Satish; Evans, Jane C.; Levy, Daniel; Wilson, Peter W.F.; Benjamin, Emelia J.; Larson, Martin G.; Kannel, William B.; Vasan, Ramachandran S. (2002). "Obesity and the risk of heart failure". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (5): 305–313. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020245. PMID 12151467.

- Haslam, DW; James, WP (October 2005). "Obesity". The Lancet. 366 (9492): 1197–1209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. PMID 16198769. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- Darvall, K.A.L.; Sam, R.C.; Silverman, S.H.; Bradbury, A.W.; Adam, D.J. (2007). "Obesity and thrombosis". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 33 (2): 223–233. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.006. PMID 17185009.

- Peter G. Kopelman; Ian D. Caterson; Michael J. Stock; William H. Dietz (2005). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4051-1672-5. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- Hammoud, Ahmad O.; Gibson, Mark; Peterson, C. Matthew; Meikle, A. Wayne; Carrell, Douglas T. (2008). "Impact of male obesity on infertility: a critical review of the current literature". Fertility and Sterility. 90 (4): 897–904. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.026. PMID 18929048.

- Stothard, Katherine J.; Tennant, Peter W. G.; Bell, Ruth; Rankin, Judith (2009). "Maternal Overweight and Obesity and the Risk of Congenital Anomalies". JAMA. 301 (6): 636–50. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.113. PMID 19211471.

- Kurth, Tobias; Gaziano, J. Michael; Berger, Klaus; Kase, Carlos S.; Rexrode, Kathryn M.; Cook, Nancy R.; Buring, Julie E.; Manson, Joann E. (2002). "Body Mass Index and the Risk of Stroke in Men". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (22): 2557–62. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.22.2557. PMID 12456227.

- Beydoun, MA; Beydoun, HA; Wang, Y (May 2008). "Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews. 9 (3): 204–218. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00473.x. PMC 4887143. PMID 18331422.

- Calle, Eugenia E.; Rodriguez, Carmen; Walker-Thurmond, Kimberly; Thun, Michael J. (2003). "Overweight, Obesity, and Mortality from Cancer in a Prospectively Studied Cohort of U.S. Adults". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (17): 1625–1638. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021423. PMID 12711737.

- Poulain M, Doucet M, Major GC, Drapeau V, Sériès F, Boulet LP, et al. (2006). "The effect of obesity on chronic respiratory diseases: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies". CMAJ. 174 (9): 1293–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051299. PMC 1435949. PMID 16636330.

- Esposito, Katherine; Giugliano, Francesco; Di Palo, Carmen; Giugliano, Giovanni; Marfella, Raffaele; d'Andrea, Francesco; d'Armiento, Massimo; Giugliano, Dario (2004). "Effect of Lifestyle Changes on Erectile Dysfunction in Obese Men". JAMA. 291 (24): 2978–84. doi:10.1001/jama.291.24.2978. PMID 15213209.

- Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, et al. (August 2002). "Obesity and the risk of heart failure". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (5): 305–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020245. PMID 12151467.

- Haslam DW, James WP (October 2005). "Obesity". Lancet. 366 (9492): 1197–209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. PMID 16198769.

- Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. (May 2006). "Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26 (5): 968–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.7066. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000216787.85457.f3. PMID 16627822.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. (2004). "Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study". Lancet. 364 (9438): 937–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. PMID 15364185.

- "Obesity and Overweight" (PDF). Fact Sheet. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health, World Health Organization. 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- Tsigos C, Hainer V, Basdevant A, et al. (2008). "Management of obesity in adults: European clinical practice guidelines". Obes Facts. 1 (2): 106–16. doi:10.1159/000126822. PMC 6452117. PMID 20054170. as PDF Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Walker, W. Allan; Blackburn, George L. (July 2005). "Science-based solutions to obesity: What are the roles of academia, government, industry, and health care?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 82 (1): 207S–210S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/82.1.207S. PMID 16002821.

- Rice, T. M.; Zhu, M. (January 21, 2013). "Driver obesity and the risk of fatal injury during traffic collisions". Emergency Medicine Journal. 31 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201859. PMID 23337422. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- Ingram DD, Mussolino ME (2010). "Weight loss from maximum body weight and mortality: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Linked Mortality File". Int J Obes. 34 (6): 1044–1050. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.41. PMID 20212495.

- Adams JP; Murphy PG (July 2000). "Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care". Br J Anaesth. 85 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.91. PMID 10927998. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- Kushner, Robert (2007). Treatment of the Obese Patient (Contemporary Endocrinology). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-59745-400-1. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- Jebb, SA; Prentice, AM (November 1995). "Is obesity an eating disorder?". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 54 (3): 721–8. doi:10.1079/pns19950071. PMID 8643709.

- World Health Organization (April 2019). "ICD-11 - Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int.

- "Obesity and overweight Fact sheet N°311". WHO. January 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Sainsbury, Amanda (March 18, 2014). "Call for an urgent rethink of the 'health at every size' concept". J Eat Disord. 2 (8): 8. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-2-8. PMC 3995323. PMID 24764532.

- Katz, David (October 17, 2012). "Why I Can't Quite Be Okay With 'Okay at Any Size'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- Mundasad, Smitha (May 17, 2017). "Fat but fit is a big fat myth". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018 – via bbc.co.uk.

- "'Healthy obesity' is a myth, study suggests". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2018.