Harry Burton (Egyptologist)

Harry Burton (13 September 1879 – 27 June 1940) was an English archaeological photographer and Egyptologist, best known for his photographs of excavations in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. His most famous photographs are the 1,400 he took documenting Howard Carter's excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb from 1922 to 1932.[1]

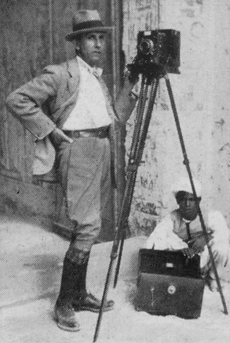

Harry Burton | |

|---|---|

Burton outside Tutankhamun's tomb, 1923 | |

| Born | 13 September 1879 Stamford, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 27 June 1940 (aged 60) Asyut, Egypt |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Photographer and Egyptologist |

| Known for | Archaeological photography, notably of Tutankhamun's tomb |

| Spouse(s) | Minnie Catherine née Duckett, (married 1914) |

| Children | None |

Life and work

Burton was born in Stamford, Lincolnshire, England, to journeyman cabinet maker William Burton and Ann Hufton, the fifth of eleven children.[2]

In his teens he began to work for the art historian Robert Henry Hobart Cust and in 1896 moved to Florence, Italy, acting as Cust's secretary and establishing a reputation as an art photographer.[2]

While in Florence, Burton met Theodore M. Davis, a wealthy American lawyer who sponsored a number of excavations of ancient tombs in Egypt. When in 1910 Cust returned to England, Burton went to Egypt, where Davis employed him as a photographer to record his excavations, including the artefacts found.[3] Burton also supervised a number of tomb excavations and clearances, including KV3 and KV47 in 1912, and KV7 in 1913–14.[4]

When Davis relinquished his excavation permit in 1914, Burton was engaged by the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Egyptian Expedition to serve as their official photographer, often working closely with Herbert E. Winlock. Over the next few years Burton worked with the Metropolitan team on numerous excavations, mostly around Thebes. His photographs frequently appeared in the Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other publications, although they were often not credited.[5]

Tutankhamun's tomb

In November 1922 Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun, its contents largely intact. Carter realised that "the first and pressing need was for photography, for nothing could be touched until a complete photographic record had been made, a task involving technical skill of the highest order."[6] The Metropolitan Museum's excavation team, working nearby, readily agreed to Carter's request for the loan of Burton to formally photograph the findings of the British excavation at Tutankhamun's tomb.[7]

In total, Burton spent ten years photographing Tutankhamun's tomb and its artefacts, with over 1,400 photographs preserved.[8][9] Burton used gelatine silver glass plates that recorded a high quality detailed image. For lighting he preferred sunlight reflected into the tomb by mirrors, sometimes over a distance of 100 feet, the light caught by reflectors that were kept constantly in motion to disperse the light evenly on the subject.[10] Burton also made use of two movable powerful electric standard lamps that Carter had installed in the dark tomb, producing an even light that could produce a high quality photograph on a slow exposure. To develop the pictures Burton used a previously cleared tomb nearby,[11] requiring constant journeys between tombs. Carter commented "These periodic dashes of his from tomb to tomb must have been a godsend to the crowd of curious visitors who kept vigil above the tomb, for there were many days during the winter in which it was the only excitement they had."[12] Burton made use of early colour autochrome plates, with the Illustrated London News publishing his colour photographs in November 1923.[8] Burton also learned to operate a motion picture camera, using it to record objects as they were removed from the tomb, as well as producing some of the earliest documentary film footage of life in the Nile valley.[13]

While working on Tutankhamun’s tomb, Burton continued to do photographic work for the Metropolitan Museum's concession at nearby Deir el-Bahari, this taking up much of his time from 1927.[14] He however continued to support Carter until the completion of the Tutankhamun clearance in 1932,[15] the two remaining on good terms, with Carter later naming him as an executor of his will.[11]

Later work

From 1931 to 1934 Burton worked at the Metropolitan concession further down the Nile at Lisht.[16] He remained in Egypt after the Metropolitan Museum ceased its major excavations in 1935, and continued to record other monuments and artefacts.[17] From 1937 Burton's health deteriorated. He died of diabetes in Egypt on 27 June 1940, aged 60. He was buried in the American cemetery in Asyut.[16]

On 18 July 1914 Burton married Minnie Catherine Young at Chelsea Registry Office in London. When not in Egypt, they lived mainly in Florence.[18] Minnie outlived her husband, dying in Florence in May 1957. The couple had no children.[19]

Legacy

While the 1,400 images[9] from the tomb of Tutankhamun are widely known, and played a significant part in the "Egyptomania" of the 1920s,[20] Burton also produced many other photographic records of the highest quality, including 7,500 for the Metropolitan Museum, over 3,000 of Theban tombs and monuments and 600 of antiquities in Cairo and Italy.[8]

Burton's key role in photographing archaeological finds, including those relating to Tutankhamun, was often downplayed or overlooked. His pictures were frequently published without attribution, he rarely featured in press reports, with only brief mentions in contemporary books.[11] He however earned a reputation among Egyptologists as the finest archaeological photographer of the time.[21] Carter valued his work highly, describing his photographs as "of outstanding beauty as well as great archaeological value".[22] In May 1923 Carter wrote to Albert Lythgoe, who had agreed the loan of Burton from the Metropolitan concession, confirming that Burton had completed his work "in a splendid and admirable manner. In fact, I do not know how to praise his work sufficiently. He had a colossal task which he carried out to the end in the most efficient manner possible, and I should like to convey through you my most sincere gratitude to your trustees and Director for his good aid."[23]

Burton's photographs have featured in a number of exhibitions:

- 2001: The Pharaoh's Photographer: Harry Burton, Tutankhamun, and the Metropolitan's Egyptian Expedition, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art;[13]

- 2006: Wonderful Things! The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun: The Harry Burton Photographs, at the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute;[24]

- 2006-07: Discovering Tutankhamun: The Photographs of Harry Burton, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art;[17]

- 2014: Discovering Tutankhamun, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, featured many of Burton's original photographs alongside records and drawings from the Griffith Institute;[25]

- 2018: Photographing Tutankhamun, at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, showed many of Harry Burton's photographs.[20]

References

- Dawson, Uphill & Bierbrier 1995.

- Ridley 2013, p. 118.

- Ridley 2013, p. 119.

- Ridley 2013, p. 120.

- Ridley 2013, pp. 121-123.

- Carter 1923, pp. 107-108.

- Ridley 2013, p. 124.

- Ridley 2013, p. 129.

- Some sources say up to 3,400 photos, (e.g. BBC article) This may include unpublished items.

- Ridley 2013, p. 128.

- Ridley 2013, p. 125.

- Carter 1923, pp. 127.

- "The Pharaoh's Photographer: Harry Burton, Tutankhamun. 2001 Expedition". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- James 1992, p. 162.

- Ridley 2013, p. 126.

- Ridley 2013, p. 127.

- "Discovering Tutankhamun: The Photographs of Harry Burton. 2006-7 Exhibition Overview". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Ridley 2013, p. 121.

- "Diary of Minnie Burton". Griffith Institute. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Discovering King Tutankhamun's tomb: Harry Burton's photographs". BBC News website. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Harry Burton: The Pharaoh's Photographer". The Met: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Carter 1927, p. Preface.

- James 1992, pp. 262-263.

- "Wonderful Things! The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. 2006 Exhibition". Oriental Institute Website. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Discovering Tutankhamun. 2014". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

Sources

- Carter, Howard (1923). The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume I. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, Howard (1927). The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume II. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawson, W; Uphill, E; Bierbrier, M (1995). Who Was Who in Egyptology, 3rd edition. Egypt Exploration Society, London. ISBN 0856981257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, T G H (1992). Howard Carter. Kegan Paul International, London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ridley, Ronald T (2013). The Dean of Archaeological Photographers: Harry Burton Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 99, 2013. SAGE Publishing, California.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harry Burton. |

External links

- Burton's Tutankhamun photographs: online gallery All of Burton's photographs of the Tutankhamun excavation (The Griffith Institute)

- Wonderful Things! The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun: The Harry Burton Photographs

- Burton, Harry: Tutankhamun tomb photographs: a photographic record in 5 albums containing 490 original photographic prints (Heidelberg University)

- Lecture: Photographing Tutankhamun: How the Camera Helped Create 'King Tut' - Christina Riggs, 7 November 2018 (Harvard Museums of Science & Culture)