Haman

Haman (Hebrew: המן Hâmân; also known as Haman the Agagite or Haman the evil) is the main antagonist in the Book of Esther, who according to the Hebrew Bible was a vizier in the Persian empire under King Ahasuerus, commonly identified as Xerxes I (died 465 BCE) but traditionally equated with Artaxerxes I or Artaxerxes II.[1] As his epithet Agagite indicates, Haman was a descendant of Agag, the king of the Amalekites.[2]

Haman in the Hebrew Bible

As described in the Book of Esther, Haman was the son of Hammedatha the Agagite. After Haman was appointed the principal minister of the king Ahasuerus, all of the king's servants were required to bow down to Haman, but Mordechai refused to. Angered by this, and knowing of Mordechai's Jewish nationality, Haman convinced Ahasuerus to allow him to have all of the Jews in the Persian empire killed.[3]

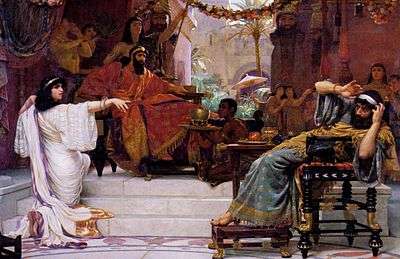

The plot was foiled by Queen Esther, the king's recent wife, who was herself a Jew. Esther invited Haman and the king to two banquets. In the second banquet, she informed the king that Haman was plotting to kill her (and the other Jews). This enraged the king, who was further angered when (after leaving the room briefly and returning) he discovered Haman had fallen on Esther's couch, intending to beg mercy from Esther, but which the king interpreted as a sexual advance.[4]

On the king's orders, Haman was hanged from the 50-cubit-high gallows that had originally been built by Haman himself, on the advice of his wife Zeresh, in order to hang Mordechai.[5] The bodies of Haman's ten sons were also hanged, after they died in battle against the Jews.[6] "All the enemies of the Jews" were additionally killed by the Jews, 75,000 of them.[6]

The apparent purpose of this unusually high gallows can be understood from the geography of Shushan: Haman's house (where the pole was located) was likely in the city of Shushan (a flat area), while the royal citadel and palace were located on a mound about 15 meters higher than the city. Such a tall pole would have allowed Haman to observe Mordechai's corpse while dining in the royal palace, had his plans worked as intended.[7]

Haman in other sources

Midrash

According to midrash, his mother was named Amathlai daughter of Orvati.[8]

In Rabbinical tradition, Haman is considered to be an archetype of evil and persecutor of the Jews. Having attempted to exterminate the Jews of Persia, and rendering himself thereby their worst enemy, Haman naturally became the center of many Talmudic legends. Being at one time extremely poor, he sold himself as a slave to Mordechai.[9] He was a barber at Kefar Karzum for the space of twenty-two years.[10] Haman had an idolatrous image embroidered on his garments, so that those who bowed to him at command of the king bowed also to the image.[11]

Haman was also an astrologer, and when he was about to fix the time for the genocide of the Jews he first cast lots to ascertain which was the most auspicious day of the week for that purpose.[2] Each day, however, proved to be under some influence favorable to the Jews.[2] He then sought to fix the month, but found that the same was true of each month; thus, Nisan was favorable to the Jews because of the Passover sacrifice; Iyyar, because of the small Passover.[2] But when he arrived at Adar he found that its zodiacal sign was Pisces, and he said, "Now I shall be able to swallow them as fish which swallow one another" (Esther Rabbah 7; Targum Sheni 3).[2]

Haman had 365 counselors, but the advice of none was so good as that of his wife, Zeresh.[2] She induced Haman to build a gallows for Mordechai, assuring him that this was the only way in which he would be able to prevail over his enemy, for hitherto the just had always been rescued from every other kind of death.[2] As God foresaw that Haman himself would be hanged on the gallows, He asked which tree would volunteer to serve as the instrument of death. Each tree, declaring that it was used for some holy purpose, objected to being soiled by the unclean body of Haman. Only the thorn-tree could find no excuse, and therefore offered itself for a gallows (Esther Rabbah 9; Midrash Abba Gorion 7 (ed. Buber, Wilna, 1886); in Targum Sheni this is narrated somewhat differently).

Haman's lineage is given in the Targum Sheni as follows: "Haman the son of Hammedatha the Agagite, son of Srach, son of Buza, son of Iphlotas, son of Dyosef, son of Dyosim, son of Prome, son of Ma'dei, son of Bla'akan, son of Intimros, son of Haridom, son of Sh'gar, son of Nigar, son of Farmashta, son of Vayezatha, (son of Agag, son of Sumkei,) son of Amalek, son of the concubine of Eliphaz, firstborn son of Esau". There are apparently several generations omitted between Agag, who was executed by Samuel the prophet in the time of King Saul, and Amalek, who lived several hundred years earlier.

Josephus

Haman is mentioned by Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews. Josephus' account of the story is drawn from the Septuagint translation of the Book of Esther and from other Greek and Jewish sources, some no longer extant.

Septuagint

In the LXX, Haman is called a "Macedonian" by Xerxes (see Esther 16:10). Scholars have had two different explanations for this naming. 1. Macedonian was used to replace the word "Mede", and emphasises this when he also says that there was no Persian blood in him. (In practice the Persians and the Medes co-ruled an empire, but there was great friction between them.) 2. Another opinion is that Xerxes was calling him a Macedonian Spy, due to his insistence on causing civil war within Persia between the Jews and the Persians.

The Septuagint translates the "hang" (Hebrew: ויתלו, lit. 'hang', 'hang up') of Esther 7:9-10 as "crucify" or "impale" (Ancient Greek: σταυρωθήτω, romanized: staurōthētō, lit. 'impale'), using the same verb later used in the New Testament's Gospel of Matthew. The fifty-cubit apparatus used in the execution is described ambiguously using a word (Ancient Greek: ξύλον, romanized: xulon, lit. 'wood') which could mean a tree, a club, a stave, a gibbet, a gallows, the vertical component of a cross for crucifixion, or anything made of wood, an ambiguity already present in the original (Hebrew: העץ, lit. 'tree', 'wood').[12][13]

Vulgate

As in the Septuagint, the execution of Haman is ambiguous, suggestive of both hanging and crucifixion. The fifty-cubit object, described as xylon in the Septuagint (Ancient Greek: ξύλον, romanized: xulon, lit. 'wood'), is similarly ambiguously referred to as "wood" (Latin: lignum). The Vulgate translation of Esther 7:10 furthermore refers to a patibulum, used elsewhere to describe the cross-piece in crucifixion, when describing the fate of Haman: suspensus est itaque Aman in patibulo quod paraverat Mardocheo, 'therefore was Haman suspended on the patibulum he prepared for Mordechai'.[12] In the corner of the Sistine Chapel ceiling is a depiction in fresco of the execution of Haman by Michelangelo; Haman is shown crucified in a manner similar to typical Catholic depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus, though the legs are parted and the apparatus resembles a natural tree shorter than fifty cubits high.

Bible in English

Translations of the Book of Esther's description of Haman's execution have treated the subject variously. Wycliffe's Bible referred both to a tre (tree) and a iebat (gibbet), while Coverdale's preferred galowe (gallows). The Geneva Bible used tree but the King James Version established gallows and hang as the most common rendering; the Douay–Rheims Bible later used gibbet.[12] Young's Literal Translation used tree and hang. The New International Version, Common English Bible, and New Living Translation all use impale for Hebrew: ויתלו and pole for Hebrew: העץ.[14][15]

Purim traditions

The Jewish holiday of Purim commemorates the story of the deliverance of the Jews and the defeat of Haman. On that day, the Book of Esther is read publicly and much noise and tumult is raised at every mention of Haman's name. A type of ratchet noisemaker called in Hebrew a ra'ashan (רעשן) (in Yiddish: "grogger" or "hamandreyer") is used to express disdain for Haman. Pastry known as hamentashen (Yiddish for 'Haman's pockets'; known in Hebrew as אזני המן ozney Haman 'Haman's ears') are traditionally eaten on this day.

Etymology and meaning of the name

The name has been equated with the Persian name Omanes[16] (Old Persian: 𐎡𐎶𐎴𐎡𐏁 Imāniš) recorded by Greek historians. Several etymologies have been proposed for it: it has been associated with the Persian word Hamayun, meaning "illustrious"[16] (naming dictionaries typically list it as meaning "magnificent"); with the sacred drink Haoma;[16] or with the Persian name Vohuman, meaning "good thoughts". The 19th-century Bible critic Jensen associated it with the Elamite god Humban, a view dismissed by later scholars.[17] Ahriman, a Zoroastrian spirit of destruction, has also been proposed as an etymon.

In popular culture

Haman appeared in The Greatest Adventure: Stories from the Bible episode "Queen Esther". The 1994 animated television film Scooby-Doo! in Arabian Nights depicts Haman as an evil vizier to the sultan in its story segment, "Aliyah-Din". Mr. Lunt portrayed this biblical figure in the 2000 VeggieTales episode "Esther the Girl who Became Queen". In the South Park episode "Jewbilee", Haman is depicted as the primary antagonist, trying to enter the mortal world once more to rule over the Jews. Rhett Butler mentions Haman in Gone With the Wind when he is in jail facing the prospect of hanging.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haman. |

- Hoschander, Jacob (1918). "The Book of Esther in the Light of History". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 9 (1/2): 1–41. doi:10.2307/1451208. hdl:2027/uc1.c100234370. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1451208.

-

- Esther 3:1-6

- Esther 7:2-8

- Esther 7:9-10

- Esther 9:6-14

- Yehuda Landy, Purim and the Persian Empire, p. 83

- Bava Batra 91a

- Megillah 15a

- Megillah 16a

- Esther Rabbah 7

- "Esther 7:9-10, Apostolic Polyglot Bible English". Study Bible. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Strong's Greek: 3586. ξύλον (xulon) -- wood". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Compare translations Esther 7:9". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Compare translations Esther 7:10". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica CD-ROM Edition 1.0 1997, Haman

- A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Esther, Lewis Bayles Paton, The Biblical World, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Feb., 1909)